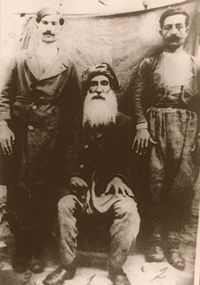

Seyid Riza

Seyîd Riza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1863 |

| Died | 1937 (Aged 74) Elazığ, Turkey |

| Notable work | He was executed because he was one of the leaders of the Dersim rebellion. |

Seyid Riza (also called as Sey Riza or Pîr Sey Riza in Zazaki), (born 1863 in Ovacık, in Dersim, died 15 November 1937). He was a Zaza[1][2][3] political leader of the Alevi Zazas,[4] a religious figure and the leader of the Kurdish movement[5] in Turkey during the 1937–1938 Dersim Rebellion.

In explaining the reason for the Kurdish rebellion to the British foreign secretary Anthony Eden he said the following:[6]

The government has tried to assimilate the Kurdish people for years, oppressing them, banning publications in Kurdish, persecuting those who speak Kurdish, forcibly deporting people from fertile parts of Kurdistan for uncultivated areas of Anatolia where many have perished. The prisons are full of non-combatants, intellectuals are shot, hanged or exiled to remote places. Three million Kurds, demand to live in freedom and peace in their own country.

Note: it is very likely that this letter was not sent by Seyid Riza, but by a Kurdish nationalist from Dersim who took refuge in Syria, named Nuri Dersimi. He was trying to get support for the Kurdish nationalist cause from Western powers (which he didn't get). The Turkish state used the letter to incriminate Seyid Riza of rebelling against the state but never proved that the letter was written by him. English archives supposedly show that the signature underneath was from Nuri Dersimi.[7]

The theory that this letter was not written and sent by Seyid Riza, is supported by the fact that he was not a nationalist leader who in the first place resisted the assimilation politics of the Turkish state, but a tribal and religious leader who was bothered by the state mingling in the local affairs.

He was tried and hanged in November 1937, after his surrender in September.

The trial and his execution

Seyid Riza was tried and sentenced after a show trial[citation needed]. Riza and his fellows were not informed about the basics of their rights and the details of their case. It was not found necessary to provide a lawyer to them.[citation needed] They were not able to understand the language of the trial (which was Turkish) since they were all Zazas. However no interpreter was provided. The trial ended after three hearings and in two weeks. The final judgement was given on a Saturday, a day which the courts do not work normally. The cause behind it was Atatürk's forthcoming visit to the region and the government's fear for a possible amnesty claim for Rıza during the visit.[8] The head judge of the court resisted to give his final decision on a holiday and alleged the lack of electricity at night time and a hangman. After giving the guarantees on lighting the courtroom with car lights and to make ready a hangman, everything was ready for the final stage. Eleven men including Seyit Rıza himself, his son Uşene Seyid, Aliye Mırze Sili, Cıvrail Ağa, Hesen Ağa, Fındık Ağa, Resik Hüseyin ve Hesene İvraime Qıji were sentenced to the death. Four of the eleven death sentences was mitigated to 30 years imprisonment sentence.[9] Seyit Rıza was almost 78 years old when the sentence was announced. This made it impossible to hang him. Yet the court accepted that he was 54, not 78. Rıza did not understand the meaning of the judgement till he sees the gallows. His final moments were witnessed by the then by Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey, İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil: Seyit Rıza understood the situation immediately after he sees the gallows. "You will hang me." he said. Then he turned to me and asked: "Did you come from Ankara to hang me?" We've exchanged glances. It was the first time I faced a man who was going to be hanged. He flashed a smile at me. Prosecutor asked whether he wanted to pray. He didn't want it. We asked his last words. "I have forty liras and a watch. You will give them to my son." he said... We brought him to the square. It was cold and there were nobody around. However, Seyit Rıza addressed to the silence and emptiness like the square is full of people. "We are the son of Karbala. We are blameless. It is shame. It is cruel. It is murder!" he said. I had goose bumps. This old man swept to the gallows, pushed the gypsy. He stringed the rope on his neck. He kicked the chair, executed himself...[10]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

His grave

Seyid Riza was buried in a secret place and its whereabouts is still unknown. There is an ongoing campaign to find his grave.[11] In his latest visit to Tunceli president Abdullah Gül was requested to disclose the location of the grave of Seyit Rıza and his companions,who were executed back then. "This is not a difficult issue, it is in the state archives." said Mr. Hüseyin Aygün a lawmaker from Dersim/Tunceli, representing the province in Turkish parliament for opposition party CHP.[12]

Popular media

- The rebellion which he led is explained in Çayan Demirel's award-winning documentary film, Dersim 38. There is also an interview with Seyid Rıza's daughter Leyla Ağlar in it.

See also

References

- ^ (according to the "encyclopedia of mass violence" seyid riza is a kurd , his religion is alevi and his language was kurdish zazaki)

- ^ (according to the french historian "Sabri Cigerli", in the book "Les Kurdes Et Leur Histoire", Seyid Riza was a Kurd)

- ^ (according to the historian "Jacqueline Sammalli" in her book "Etre Kurde, un délit?: portrait d'un peuple nié", seyid Riza is a Turkish From Turkmenistan , a Alevi leader)

- ^ Altan Tan, Kürt sorunu, Timas Basim Ticaret San As, 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-884-6, p. 28.

- ^ Celal Sayan, La construction de l'état national turc et le mouvement national kurde, 1918–1938, Volume 1, 2002, Presses universitaires du septentrion, p. 680.

- ^ McDowall, David. A Modern History of the Kurds, page 208. I.B. Tauris, 2004.

- ^ The Upper Echelons of the State in Dersim, by Abdullah Kilic and Ayca Örer, published (in Turkish) in Radikal paper, 20–24 November 2011. An English translation: http://www.timdrayton.com/a55.html

- ^ http://www.akarhuseyin.com/?page_id=1134

- ^ http://www.cafrande.org/?p=12257

- ^ http://bianet.org/bianet/biamag/118263-dersimi-caglayangil-ve-baturdan-dinliyoruz

- ^ http://www.dersimweb.de/unterschrift.pdf

- ^ http://bianet.org/english/human-rights/118086-president-gul-faces-demands-from-tunceli