Siege of Bangkok

| Siege of Bangkok | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Siamese revolution of 1688 | |||||||

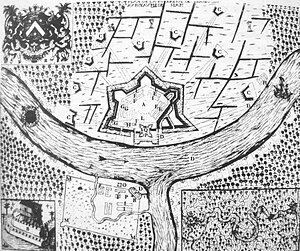

Siege of the French fortress (A) by Siamese troops and batteries (C), in Bangkok, 1688. The enclosure of the village of Bangkok represented in the lower left corner (M) is today's Thonburi.[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Phetracha | General Desfarges | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 | 200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Siege of Bangkok was a key event of the Siamese revolution of 1688, in which the Siamese people ousted the French from Siam. Following a coup d'état, in which the pro-Western king Narai was replaced by Phetracha, Siamese troops besieged the French fortress in Bangkok for four months. The Siamese were able to muster about 40,000 troops, equipped with cannon, against the entrenched 200 French troops, but the military confrontation proved inconclusive. Tensions between the two belligerents progressively subsided, and finally a negotiated settlement was reached allowing the French to leave the country.[2]

The Siege of Bangkok would mark the end of French military presence in Siam, as France was soon embroiled in the major European conflicts of the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697), and then the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1713/1714). With the end of the siege, a long period started during which Siam would remain suspicious of Western intervention. Only a few French missionaries were allowed to remain, while trade continued on a limited level with other European countries such as Holland and England.

Background

King Narai had sought to expand relations with the French, as a counterweight to Portuguese and Dutch influence in his kingdom, and at the suggestion of his Greek councilor Constantine Phaulkon.[3] Numerous embassies were exchanged in both directions, including the embassy of Chevalier de Chaumont to Siam in 1685 [4] and the embassy of Kosa Pan to France in 1686.

This led to a major dispatch of French ambassadors and troops to Siam in 1687,[5] organized by the Marquis de Seignelay. The embassy consisted of a French expeditionary force of 1,361 soldiers, missionaries, envoys and crews aboard five warships.[5] The military wing was led by General Desfarges, and the diplomatic mission by Simon de la Loubère and Claude Céberet du Boullay, a director of the French East India Company. Desfarges had instructions to negotiate the establishment of troops in Mergui and Bangkok (considered as "the key to the kingdom")[5] rather than the southern Songkla, and to take these locations if necessary by force.[5]

King Narai agreed to the proposal, and a fortress was established in each of the two cities, which were commanded by French governors.[4][6][7] Desfarges noted in his account of the events[8] that he was in command of the fortress of Bangkok, with 200 French officers and men,[9] as well as a Siamese contingent provided by King Narai, and Du Bruant was in command of Mergui with 90 French soldiers.[9][10] Another 35 soldiers with three or four French officers were assigned to ships of the King of Siam, with a mission to fight piracy.[9]

The disembarkment of French troops in Bangkok and Mergui led to strong nationalist movements in Siam directed by the Mandarin and Commander of the Elephant Corps, Phra Phetracha. By 1688 anti-foreign sentiments, mainly directed at the French and Phaulkon, were reaching their zenith.[4] The Siamese courtiers resented the dominance of the Greek Phaulkon in state affairs, along with his Japanese wife Maria Guyomar de Pinha and European lifestyle, whilst the Buddhist clergy were uneasy with the increasing prominence of the French Jesuits. The Siamese mandarinate under the leadership of Phetracha complained about the occupation force and increasingly opposed Phaulkon.[11]

Siege of Bangkok

Matters were brought to a head when King Narai fell gravely ill in March 1688. Phetracha initiated the Siamese revolution of 1688 by seizing the Royal Palace in Lopburi and putting king Narai under house-arrest on May 17–18. He also imprisoned Constantine Phaulkon on May 18, 1688,[11] and executed the king's adopted son Mom Pi on May 20.[12]

General Desfarges in Lopburi

On June 2, General Desfarges, commander of the Bangkok fortress, was invited to Lopburi by Phetracha,[12] and according to the account of one of his officers named De la Touche[13] received promises of significant personal gains, such as the naming of his eldest son, Marquis Desfarges, to a major position in the Siamese government, equivalent to that which Constantine Phaulkon had held.[14] Phetracha also required Desfarges to move his troops from Bangkok to Lopburi in order to contribute in an ongoing war with the Lao and the Cochin-Chinese.[15] Desfarges managed to leave by promising that the would send the troops demanded by Phetracha, and that he would remit the fortress of Bangkok. He also had to leave his two sons as hostages to Phetracha.[15]

Desfarges left Lopburi on June 5. As Desfarges had shown no interest in the fate of Phaulkon, Phetracha ordered Phaulkon's execution the same day.[16] Phaulkon, who had been submitted to many tortures since his arrest, was beheaded by Phetracha's own son, Ok-Phra Sorasak.[17] Desfarges returned to Bangkok on June 6, accompanied by two mandarins, including Kosa Pan, the former ambassador to France, to whom he was supposed to remit the fortress. According to Vollant de Verquains, on that same day, in a council of war with his officers, the decision was taken not to obey Phetracha, but rather to resist him and start an armed confrontation.[18]

Start of the hostilities

Phetracha moved to besiege the French fortress in Bangkok with 40,000 men,[19] and over a hundred cannon.[20] The Siamese troops apparently received Dutch support in their fight against the French,[20] and the Dutch factor Johan Keyts was accused of collaborating with the Siamese.[21]

The French had two fortresses (one in Bangkok, one in Thonburi on the other side of the Chao Phraya river) and 200 men, including officers.[20] General Desfarges was commander-in-chief, and Mr de Vertesalle was second in command.[22] For food, they also had about 100 cows, which Constance Phaulkon had had the foresight of providing them,[18] which they started to slaughter. In order to facilitate defensive work, they also burnt down the small village which was near the Bangkok fortress.[23]

The first act of war was the attack on a Chinese junk belonging to the king of Siam, which was passing by. The captain of the junk had refused to give supplies to French, especially the salt which was needed to salt meat, and therefore was fired on repeatedly.[18]

Thonburi fortress

The French initially occupied both sides of the Chao Phraya in Bangkok, with two fortresses, one on the left bank (the Bangkok fortress) and one on the right bank (the Thonburi fortress). Seeing that the position would be difficult to defend, especially since communications would become nearly impossible at low tide, the French decided to regroup in the larger fortress, on the left bank of the river. The French destroyed parts of the fortifications, split 18 cannons and spiked the rest.[23] Soon after they left the smaller fort, Siamese troops invested it and began to set up cannons and mortars to bombard the French positions. Forty cannons were set up there, which were in a very good position to shoot at the French fortress on the other side of the river.[20]

As the Siamese were using the Thonburi fortress advantageously, the French decided to launch an attack against it and destroy it. A detachment of 30 men was sent, on two longboats led by an ensign. The French were overwhelmed by the Siamese forces, however, and although several had managed to scale the ramparts, they soon had to jump from it. Four French soldiers were killed on the spot, and four later died from their wounds.[24]

Siamese encirclement of the Bangkok fortress

The Siamese then endeavored to confine the French troops in the Bangkok fortress, by building redoubts. Twelve small forts were constructed around the French fortress, each one containing between seven and ten cannons. According to the French, this was done with the help of the Dutch.[20] The Chao Praya, connecting the fortress of Bangkok to the sea, was lined with numerous forts, and was blocked at its mouth with five to six rows of huge tree trunks, an iron chain and numerous embarkations.[25] Altogether, there were seven batteries, containing 180 cannons.[26]

Since two ships of the king of Siam were out at sea being commanded by some of his officers, Desfarges sent a longboat to try to reach them, and possibly call the French in India (Pondicherry) for help.[27] The longboat was commanded by a company lieutenant and ship ensign, Sieur de Saint-Christ. He was blocked on his way to the sea, however, as numerous fortifications and Siamese soldiers had been established there. Overwhelmed, Saint-Christ self-exploded his own ship, leading to the death of hundreds of Siamese and most of the French crew except two, who were ultimately remitted to Desfarges.[27]

De-escalation and peace

In an effort to end the stalemate with the French in Bangkok, on June 24 Phetracha released the two sons of Desfarges, whom he had been holding as hostages since the visit of General Desfarges to Lopburi in early June, as well as all other French prisoners.[28] Although he tried to make peace with the French, Phetracha managed to eliminate all the viable candidates to the throne: the two brothers of the king were executed on July 9, 1688.[12][29] King Narai himself died on July 11, possibly with the help of poisoning.[30] Phetracha was crowned king on August 1, 1688, in Ayutthaya.[12] He founded the new Ban Phlu Luang dynasty.[29]

After that time, the tension around the French in Bangkok subsided, with fewer cannon shots being traded, and exchanges of food and services being resumed to a certain level. Some discussions were also cautiously started to find an agreement.[28] On September 9, the French warship Oriflamme, carrying 200 troops and commanded by de l'Estrilles, arrived at the mouth of the Chao Phraya River,[12] but was unable to dock at the Bangkok fortress as the entrance to the river was being blocked by the Siamese.[31] According to Vollant des Verquains, this put further pressure on the Siamese however to find a peaceful way out of the conflict.[32]

Desfarges finally negotiated in the end of September 1688 an agreement to leave the country with his men on board the Oriflamme and two Siamese ships, the Siam and the Louvo, provided by Phetracha.[12][33] The new king Phetracha gave back all his French prisoners. To guarantee the agreement, the French were supposed to leave the country holding two Siamese hostages, while three French hostages were supposed to remain in Siam until the Siamese ships were returned: Mgr Laneau, Bishop of Metellopolis, Véret, the head of the French factory in Siam, and Chevalier Desfarges, the younger son of General Desfarges.[34]

Maria Guyomar de Pinha

Phaulkon's Catholic Japanese-Portuguese wife, named Maria Guyomar de Pinha,[35] who had been promised protection by being ennobled a countess of France,[11] took refuge with the French troops in Bangkok, where she was able to stay from October 4–18, 1688.[16] She had managed to flee Ayutthaya with the help of a French officer named Sieur de Sainte-Marie. According to Desfarges himself, Phetracha demanded her return, threatening to "abolish the vestiges of the (Christian) religion", and he further captured dozens of French people to obtain her return: the Jesuit Father de La Breuille, 10 missionaries, fourteen officers and soldiers, six members of the French East India Company, and fourteen other French people (including three ship captains, three mirror technicians, Sieur de Billy, governor of Phuket, a carpenter named Lapie, and the musician Delaunay).[36] Desfarges, afraid of compromising the peace agreement and resume a full conflict, returned her to the Siamese on October 18, against the opinion of his officers.[11][12] Despite the promises that had been made regarding her safety, she was condemned to slavery in the kitchens of Phetracha, which remained in effect until Phetracha died in 1703.[37]

Retreat from Bangkok

Desfarges finally left with his men to Pondicherry on November 13, on board the Oriflamme and two Siamese ships, the Siam and the Louvo, provided by Phetracha.[12][38] Altogether, the siege had lasted more than four months,[27] until the negotiated settlement was reached.[39][40] Of the three French hostages who were supposed to remain in Siam until the Siamese ships were returned, only Mgr Laneau, Bishop of Metellopolis, actually remained, while Véret, the head of the French factory, and the Chevalier Desfarges, son of the General, managed to flee on board the Oriflamme.[34] The Siamese, angered by the non-respect of the agreement, seized some of the French baggage, about 17 remaining French soldiers, and put Mgr Laneau in prison for several years. On November 14, the day following the departure of the French, the 1644 Treaty and Alliance of Peace between Siam and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was renewed, guaranteeing the Dutch the deerskin export monopoly they had had, and giving them freedom to trade freely in Siamese ports with anyone. They also obtained a renewal of their export monopoly on Ligor for tin (originally granted by king Narai in 1671).[41] The Dutch, and to lesser extent the English, continued to trade in Ayutthaya, although with difficulty.[42]

Aftermath

Once arrived in the small French settlement of Pondicherry, some of the French troops remained to bolster the French presence there, but most left for France on February 16, 1689 aboard the French Navy Normande and the French Company Coche, with the engineer Vollant des Verquains and the Jesuit Le Blanc aboard.[43] The two ships were captured by the Dutch at the Cape of Good Hope, however, because the War of the Augsburg League had started.[34] After a month in the Cape, the prisoners were sent to Zeeland where they were kept at the prison of Middelburg. They were able to return to France through a general exchange of prisoners.[34][44]

On April 10, 1689, Desfarges – who had remained in Pondicherry – led an expedition to capture the tin-producing island of Phuket in an attempt to restore some sort of French control in Siam.[16][45] The island was captured temporarily in 1689,[46] but the occupation led nowhere, and Desfarges returned to Pondicherry in January 1690.[47] Recalled to France, he left 108 troops in Pondicherry to bolster defenses, and left with his remaining troops on the Oriflamme and the Company ships Lonré and Saint-Nicholas on February 21, 1690.[48] Desfarges died on his way back trying to reach Martinique, and the Oriflamme later sank on February 27, 1691, with most of the remaining French troops, off the coast of Britanny.[49]

France was unable to stage any comeback or organize a retaliation due to its involvement in major European conflicts: the War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697), and then the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1713/1714).[50] France only resumed official contacts in 1856, when Napoleon III sent an embassy to King Mongkut led by Charles de Montigny.[51]

See also

- Battle of Dien Bien Phu, 1954 – battle marking the end of the French military presence in Vietnam.

Notes

- ^ Vollant des Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.95-96

- ^ Siam: An Account of the Country and the People, Peter Anthony Thompson, 1910 p.28

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.9-10

- ^ a b c Martin, p.25

- ^ a b c d Smithies 2002, p.10

- ^ Note 6, Smithies 2002, p.99

- ^ Dhiravat na Prombejra, in Reid p.251-252

- ^ Account of the revolutions which occurred in Siam in the year 1688 by General Desfarges, translated by Smithies, Michael (2002) Three military accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam.

- ^ a b c Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.25

- ^ De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.76

- ^ a b c d Smithies 2002, p.11

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smithies 2002, p.184

- ^ Relation of what occurred in the kingdom of Siam in 1688 by De la Touche, translated in Smithies, Michael (2002), Three military accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam

- ^ De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.68

- ^ a b De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.69

- ^ a b c Smithies 2002, p.18

- ^ Vollant de Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.134

- ^ a b c Vollant de Verquains, Smithies 2002, p.137 Cite error: The named reference "Smithies137" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.66

- ^ a b c d e De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.70 Cite error: The named reference "Smithies70" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Smithies, p.93

- ^ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.37

- ^ a b Desfarges, in Smithies, p.41

- ^ Vollant des Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.139

- ^ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.52

- ^ Vollant des Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.140

- ^ a b c De la Touche, in Smithies 2002, p.71

- ^ a b Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.48

- ^ a b Dhiravat na Prombejra, in Reid p.252

- ^ Vollant des Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.145

- ^ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.49

- ^ Vollant des Verquains, in Smithies 2002, p.148

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.73

- ^ a b c d Smithies 2002, p.12

- ^ Note 9, Smithies 2002, p.100

- ^ Desfarges, in Smithies 2002, p.50

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.11-12

- ^ De la Touche in Smithies 2002, p.73

- ^ Martin, p. 26

- ^ Black, p.106

- ^ Dhivarat na Pombejra in Reid, p.265

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.181

- ^ Smithies, p.89

- ^ Note 1, Smithies 2002, p.19

- ^ Hall, p.350

- ^ Dhivarat na Prombejra, in Reid p.266

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.185

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.179

- ^ Smithies 2002, p.16/p.185

- ^ Dhiravat na Pombejra, in Reid, p.267

- ^ "Threats to National Independence : 1886 - 1896", Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

References

- Black, Jeremy, 2002, Europe and the World, 1650-1830, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-25568-6

- Hall, Daniel George Edward, 1964, A History of South-east Asia, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-38641-2

- Martin, Henri, 1865, Martin's History of France: The Age of Louis XIV, Walker, Wise and co., Harvard University

- Reid, Anthony (Editor), Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era, Cornell University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8014-8093-0

- Smithies, Michael (2002), Three military accounts of the 1688 "Revolution" in Siam (Jean Vollant des Verquains History of the revolution in Siam in the year 1688, Desfarges Account of the revolutions which occurred in Siam in the year 1688, De la Touche Relation of what occurred in the kingdom of Siam in 1688), Itineria Asiatica, Orchid Press, Bangkok, ISBN 974-524-005-2.