Siege of Silistria (1854)

| Siege of Silistria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crimean War | |||||||

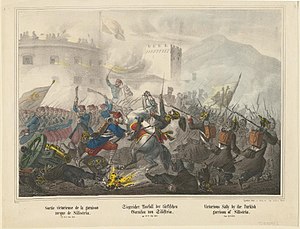

"Victorious sally by the Turkish garrison of Silistria" Illustration by unknown artist | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000–18,000[2] |

50,000–90,000[3][a] 266 guns[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,400 killed[5] |

419[6][b] to 2,500[citation needed] killed 2,455[7] to 10,000 death & wounded[9] | ||||||

The siege of Silistria, or siege of Silistra, took place during the Crimean War, from 11 May to 23 June 1854, when Russian forces besieged the Ottoman fortress of Silistria (present-day Bulgaria). Sustained Ottoman resistance had allowed French and British troops to build up a significant army in nearby Varna. Under additional pressure from Austria, the Russian command, which was about to launch a final assault on the fortress town, was ordered to lift the siege and retreat from the area, thus ending the Danubian phase of the Crimean War.[3]

Background

[edit]On 20 March 1854, following the winter lull in campaigning, a Russian army consisting of two army corps crossed the Danube advancing into Ottoman territory. In the east, an army numbering 50,000 under General Alexander von Lüders crossed the border from Bessarabia into Dobruja to occupy designated strong points. The Russians advanced quickly and at the beginning of April reached the lines of the Trajan's Wall, 30 miles east of Silistria. Meanwhile, the central force under Prince Mikhail Gorchakov crossed the river and advanced to lay siege to Silistria on 14 April. Silistria was heavily fortified and defended by an Ottoman garrison between 12,000[10] and 18,000[2] men under the command of Ferik Musa Hulusi Pasha known as Musa Pasha, and assisted by foreign advisors.[10] An Ottoman force under Omar Pasha numbering 40 to 45,000 was based to the south of Silistria in Şumnu.[c][12]

Action

[edit]Silistria had ancient Roman foundations, it was built up by Turkey as a major fortress and trading centre, fortified with an inner Citadel it had an outer ring of ten forts.[13] The Ottoman army at Silistria was composed mostly of Albanians and Egyptians[12] under the command of Musa Pasha. About six British Officers were helping the Ottomans, most notably Robert Cannon (Behram Pasha). Captain James Butler and Lieutenant Charles Nasmyth,[d] were some of the foreign officers directing Ottoman troops against the Russians. Nasmyth arrived in Silistria on 28 March 1854, before it was besieged by the Russians. Nasmyth and Butler of the Ceylon Rifles, offered their services to the garrison, both men had served with the East India Company Army.[14]

On 5 April the vanguard of the Russian force under General Karl Andreyevich Schilder and his assistant military engineer Lieutenant-Colonel Eduard Totleben arrived at the fortress and commenced the siege by building entrenchments. Schilder had taken Silistria in 1829 by mining operations, this time Totleben was in charge of fortifications and sapper work.[10] However, they were unable to completely surround the town, and the Ottoman forces were able to keep the garrison supplied. On 22 April Field Marshal Prince Ivan Paskevich, the commander of all Russian forces took personal control of the Danube campaign and arrived from Warsaw to Bucharest to take charge of the siege.[15]

On 28 May, after a sally from the Turkish Garrison, the heavily fortified fort of Arab Tabia, a key outwork, was assaulted and briefly captured, but the attackers were left without support and were ordered to withdraw, losing 700 men in total,[16] including General Dmitriy Selvan, who was mortally wounded in the assault.[17] Official Ottoman proclamations announced that their losses were 189 men.[17] Musa Pasha, the garrison commander, died on 2 June killed by shrapnel while performing prayers, he was replaced by British officers Butler and Nasmyth.[18] Paskevich in his reports to Nikolai stated that the Ottomans were defending the city with good strategic knowledge because of the assistance of foreign officers.[19]

On 10 June Field Marshal Paskevich claimed to have been hit when an Ottoman shell exploded nearby.[13] Although he was not wounded, the seventy-two-year old Field Marshal retired and returned to Warsaw while his place was taken by General Gorchakov.[6] On 13 June Schilder was also wounded and died shortly after, a week later, on 20 June, Arab-Tabia was finally captured.[13] On 21 June the Russians prepared to storm the main fortress, the attack was scheduled for 4 am.[19][6]

The siege of Silistria must be raised if the fortress is not yet taken at the receipt of this letter.

— Nicholas I of Russia to Field Marshal Paskevich, 13 June 1854, [6]

At 2 am on 21 June, just two hours before the assault was due to take place and in the midst of troop movements, Gorchakov received orders from Paskevitch to raise the siege and return to his positions north of the Danube. The concentration of allied troops in the vicinity of Varna, 50,000 French and 20,000 British, as well as Austria's new treaty with Turkey, signed on 14 June, made Nicholas I order a strategic withdrawal.[19] The order was obeyed immediately on 24 June the Russian army crossed the Danube destroying the bridge behind them, the Ottoman army did not follow. The Russian's casualties were 2,500 dead and 1783 wounded during the siege.[8]

Aftermath

[edit]Most scholars agree that the Russian offensive was not stopped by Ottoman resistance but by diplomatic pressure and the threat of military action by Austria.[20][6][19] The Austrians had been concentrating troops (said to number 280,000[4]) along the borders of Wallachia and Moldavia and had warned Russia not to cross the Danube,[4] then on 30 June 1854, 12,000 French troops commanded by Vice-Admiral Bruat arrived at Varna where 30,000 British troops had already arrived on 27 June,[21] that recent buildup added pressure on Russian command to abandon the siege and retreat back into Russia across the Prut.[3] In order to save face the Russians called their retreat a "strategic withdrawal".[19]

Following the retreat Nicholas I acceded to the Austrian-Ottoman occupation of the Danubian principalities thus signaling the end of the Danubian phase of the war.[3] The Turks under Omar Pasha then crossed the Danube into Wallachia and went on the offensive engaging the Russians in the city of Giurgevo in early July 1854.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ By May 1854, the Russian forces around Silistria had reached 90,000 men, at the time the single largest Russian siege force ever deployed against an Ottoman fortress.[4]

- ^ or 530 killed[7]

- ^ Omar Pasha was a former Serbian Orthodox Austrian soldier known as Mihajlo Latas[11]

- ^ Nasmyth was also news correspondent for the London Times, Nasmyth's letters in the Times, from April to June 1854, described the siege in details until his wounding and death.[2]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Sweetman 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Reid 2000, p. 256.

- ^ a b c d Ágoston and Masters 2010, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d Candan Badem 2010, p. 184.

- ^ Tyrrell 1855, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e Winfried Baumgart 2020, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Egorshina & Petrova 2023, p. 432. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEEgorshinaPetrova2023432" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Ponting 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Siege of Sillistra, Nineteenth-century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View, ed. Byron Farwell, (W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), p.760.

- ^ a b c Candan Badem 2010, p. 183.

- ^ Cuvalo 2010, p. 138.

- ^ a b Ágoston and Masters 2010, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Ponting 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Reid 2000, p. 254.

- ^ Ponting 2011, p. 62.

- ^ Russell 1865, p. 17.

- ^ a b Candan Badem 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Jaques & Showalter 2007, p. 945.

- ^ a b c d e Candan Badem 2010, p. 186.

- ^ Hötte 2017, p. 7.

- ^ The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal 1858, p. 241.

- ^ Small 2018, p. 63.

References

[edit]- Egorshina, O.; Petrova, A. (2023). "Восточная война 1853-1856" [The Eastern War of 1853-1856]. История русской армии [The history of the Russian Army] (in Russian). Moscow: Edition of the Russian Imperial Library. ISBN 978-5-699-42397-2.

- ́Ágoston, G.A.; Masters, B.A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Facts on File Library of World History. Facts On File, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Candan Badem (2010). "The" Ottoman Crimean War: (1853 - 1856). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18205-9.

- Cuvalo, A. (2010). The A to Z of Bosnia and Herzegovina. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7647-7.

- The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. Arch. Constable & Comp. 1858.

- Hötte, H.H.A.; Demeter, G.; Turbucs, D. (2017). Atlas of Southeast Europe: Geopolitics and History. Volume Three: 1815-1926. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 The Near and Middle East. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-36181-2.

- Jaques, T.; Showalter, D.E. (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33539-6.

- Ponting, Clive (15 February 2011). The Crimean War: The Truth Behind the Myth. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-9311-6.

- Reid, J.J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839-1878. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte des östlichen Europa. F. Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-07687-6.

- Russell, W.H. (1865). General Todleben's History of the Defence of Sebastopol, 1854-5: A Review. Tinsley Brothers.

- Small, H. (2018). The Crimean War: Europe's Conflict with Russia. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-8742-4.

- Sweetman, J. (2014). Crimean War. Essential Histories. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-97650-7.

- Tyrrell, H. (1855). The History of the War with Russia: Giving Full Details of the Operations of the Allied Armies. London Print. and Publishing Company.

- Winfried Baumgart (9 January 2020). The Crimean War: 1853-1856. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-08345-5.

General references

[edit]- Morell, J.R. (1854). The Neighbours of Russia: And History of the Present War to the Siege of Sebastopol. T. Nelson and sons.