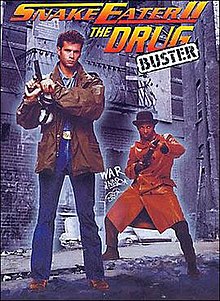

Snake Eater II: The Drug Buster

| Snake Eater II: The Drug Buster | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | George Erschbamer |

| Written by | Don Carmody John Dunning Michael Paseornek |

| Produced by | John Dunning Irene Litinksy Jeffrey Barmash (associate) André Link (executive) |

| Starring | Lorenzo Lamas Larry B. Scott Michele Scarabelli |

| Cinematography | Glen MacPherson |

| Edited by | Jacqueline Carmody |

| Music by | John Massari |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Cinépix/Famous Players Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | CAD$2,367,754[1] |

Snake Eater II: The Drug Buster, also known as Snake Eater's Revenge,[2] is a 1991 action film directed by George Erschbamer, starring Lorenzo Lamas, Larry B. Scott and Michele Scarabelli. It is the sequel to 1989's Snake Eater. Lamas returns as ex-Marine Jack "Soldier" Kelly, who teams with new sidekick "Speedboat" (Larry B. Scott) to protect an inner city neighborhood from drug traffickers.

Plot

[edit]After several inner city youths die from overdose after consuming drugs cut with rat poison, police officer Jack "Soldier" Kelly arms himself with weapons he saved from his Marine days, and busts into a local drug house from which the substance was sold, killing four dealers in the process. His renegade efforts lead to his arrest, but he is saved from jail thanks to his lawyer's insanity plea, and sent to an insane asylum under the supervision of Dr. Pierce. There, he meets many "crazy" characters such as a neurotic computer programmer, a sex addicted former televangelist, and the pyromaniac known as "Torchy" which he busted himself in the previous film. This cast of oddball characters both assist and hinder Soldier's attempts to leave the facility to continue his vendetta against the drug cartel. After finding a secret way out of the institution, Kelly reconnects with an inner city acquaintance, the fast-talking speedboat, and enlists his aid to commit further attacks on local drug dealers, which make use of his weapon crafting skills. The trail leads them to a mansion housing the cartel's headquarters, and the two men do away with the crime bosses, poisoning them with their own tainted supply. Back at the asylum, Kelly is informed by Dr. Pierce that he has been found not guilty of the murders that originally led to his psychiatric internment by reason of temporary insanity, as the motley crew of patients he bonded with during his stay rejoices.

Cast

[edit]- Lorenzo Lamas as Officer Jack "Soldier" Kelly

- Michele Scarabelli as Dr. Pierce

- Larry B. Scott as "Speedboat"

- Jack Blum as Billy Ray

- Ron Palillo as "Torchy"

- Sonya Biddle as Lucinda

- Kathleen Kinmont as Detective Lisa Forester

- Harvey Atkin as Sidney Glassberg

Production

[edit]The second installment was greenlit and announced right after the original had wrapped filming, and well before it was released. Its provisional title was Kelly's Crazies: The Snake Eater's Revenge.[3] Cinépix exercised their option on Lamas' services for a sequel on December 13, 1988, two months after the end of the first shoot.[4] The script for Snake Eater II was adapted from an unsold script by Carmody, which predated the first Snake Eater.[5]

In early February 1989, a casting call was issued for the role of new sidekick "Speedboat", described as "a young Eddie Murphy type, with a mile-a-minute mouth", with a salary projected to be in the range of CAD$10,000 to 15,000 for about four weeks of work.[6] A tryout was organized on March 19 for people of color, in order to cast the parts of other inner city inhabitants.[7] Lamas also arranged for his new wife, Kathleen Kinmont, who supposedly had strict rules regarding his contacts with other actresses, to have a role in the film.[8]

Principal photography was originally scheduled to last seven weeks from March 27 to May 12, 1989.[4] However, the shoot was shortened and delayed to April 9,[6] and eventually began on April 11. It was scheduled to continue until May 7. Filming took place in Cinépix's hometown of Montreal.[9] The company's archive lists the final budget as CAD$2,367,754.[1]

Release

[edit]While the film was meant to be released quickly after the first one, its arrival in major territories was delayed by legal proceedings involving Quebec film support fund SOGIC. Due to the script's authors being Americans (albeit based in Canada), and it originating as a standalone intellectual property, SOGIC deemed that the project was an American picture that had been abusively repackaged as Canadian to exploit the provincial tax incentive program, potentially exposing Cinépix and its backers to financial penalties. The producers eventually prevailed, but the proceedings lasted about one year.[5] International sales were handled by Pierre David's Image Organization.[2]

Theatrical

[edit]In its native Canada, Snake Eater II received a theatrical release in Quebec and Ontario, opening on January 25, 1991, in both provinces via Cinépix/Famous Players Distribution.[10][11]

Home media

[edit]In Canada, the film was released on home video in the fourth week of April 1991.[12] Unlike the first one, Snake Eater II was released straight-to-video in the U.S., premiering on VHS on April 11, 1991.[13] The tape was distributed by Paramount Home Video in the U.S. and Cinépix affiliate C/FP Video in Canada.[14] In the U.K., the film appeared in February 1991 on the 20:20 Vision label.[15] These were all predated by the film's Australian release courtesy of Palace Entertainment in the spring of 1990, which cracked the Top 20 rental charts published by Melbourne's The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald.[16][17]

Reception

[edit]Snake Eater received mostly negative reviews, albeit not as poor as the original. Blockbuster Video's Guide to Movies and Videos deemed the picture to be a marginal improvement, finding that it offered "more action" and "a touch more story than the first".[18] Ballantine Books' Video Movie Guide, which had lambasted its predecessor, was not as harsh towards the film but still knocked Lamas' character for perceived similarities to Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon, dismissing it as a "rip-off action flick".[19]

In his book Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival, journalist Anderson Cooper briefly recalls seeing the film in a Nairobi, Kenya, theater while working in the country, and contrasting the lead character's style with the comparably understated demeanor of actual "snake eaters" he met in operations a few weeks later.[20]

Further sequels

[edit]Lamas returned for one more sequel, Snake Eater III: His Law (1992). A fourth movie, Hawk's Vengeance, which starred Gary Daniels rather than Lamas, followed in 1997.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Snake Eater II, The Drug Buster". cinepix.ca. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Ryan, James (1 March 1990). "Just another wacko day at the film market". Fresno Bee. BPI. p. F5 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ Kane, Joe (November 16, 1988). "Phantom of the Movies". The Daily News. New York. p. 37 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ a b Dunning, John (December 13, 1988), Snake Eater II Option letter for Lorenzo Lamas (PDF) (written correspondence), Cinépix

- ^ a b Dunning, John; Brownstein, Bill (2014). You're Not Dead Until You're Forgotten: A Memoir. Montreal; Kingston: McGill–Queen's University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780773544024.

- ^ a b Schnurmacher, Thomas (February 6, 1989). "Fictitious rock star resurrected for movie sequel". The Gazette. Montreal. p. B-10 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ Schnurmacher, Thomas (March 18, 1989). "Even The Eagle has landed as celebs pack St. Sauveur". The Gazette. Montreal. p. B-10 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ Lamas, Lorenzo; Lensburg, Jeff (2014). Renegade at heart: An Autobiography. Dallas: BenBella. p. 158. ISBN 9781940363394.

- ^ Levesque, Jim (April–May 1989). "On Location". Cinema Canada. No. 162. Montreal: Cinema Canada Magazine Foundation. p. 35.

- ^ "L'Indomptable II: L'Anti Drogue advertisement". La Presse (in French). Montreal. January 25, 1991. p. E4.

- ^ "Snake Eater II: The Drug Buster advertisement". The Toronto Star. January 25, 1991. p. D2 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ "Video: This week's releases". The Toronto Star. April 21, 1991. p. C2 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ "List of video release dates". Anderson Independent-Mail. Tribune Media Service. April 10, 1991. p. 4E – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ "Snake Eater II: The Drug Buster". vhscollector.com. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ Speed, F. Maurice; Cameron-Wilson, James (1992). "Video releases". Film review 1991–2 (including video releases). London: Virgin Books. p. 142. ISBN 9781852273187.

- ^ "Top Videos". The Age. Melbourne. April 19, 1990. p. Green Guide 12 – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ "Top 20". Sydney Morning Herald/The Guide. May 7, 1990. p. 5S – via newspapers.com (subscription required) .

- ^ Castell, J. Ronald, ed. (September 1996) [1994, 1995]. Blockbuster Entertainment Guide to Movies and Videos 1997. New York: The Philip Lief Group; Island Books. ISBN 0440222753.

- ^ Martin, Mick; Porter, Marsha (November 1992). Video Guide Movie 1993. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 116. ISBN 0345379446.

- ^ Anderson, Cooper (2007). Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival. New York: Harper. p. 91. ISBN 9780061136689.