Sonderkommando

| Sonderkommando | |

|---|---|

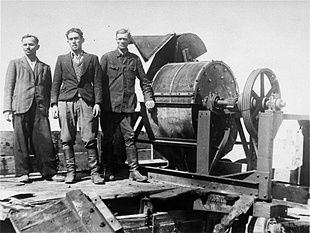

Jewish work-detail next to a bone crushing machine | |

| Location | German-occupied Europe |

| Date | 1942–1945 |

| Incident type | Removal of Holocaust evidence |

| Perpetrators | Schutzstaffel (SS) |

| Participants | Arbeitsjuden |

| Camp | Extermination camps including Auschwitz, Belzec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór and Treblinka among others |

| Survivors | Zalman Gradowski, Filip Müller, Henryk Tauber, Leib Langfus, Morris Venezia, Henryk Mandelbaum, Dario Gabbai |

Sonderkommandos were work units made up of German Nazi death camp prisoners. They were composed of prisoners, usually Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber victims during the Holocaust.[1][2] The death-camp Sonderkommandos, who were always inmates, should not be confused with the SS-Sonderkommandos which were ad hoc units formed from various SS offices between 1938 and 1945.

The term itself in German means "special unit", and was part of the vague and euphemistic language which the Nazis used to refer to aspects of the Final Solution (cf. Einsatzkommando units of the Einsatzgruppen death squads).

Work, living conditions, and death

Sonderkommando members did not participate directly in killing; that responsibility was reserved for the guards, while the Sonderkommandos' primary responsibility was disposing of the corpses.[3] In most cases they were inducted immediately upon arrival at the camp and forced into the position under threat of death. They were not given any advance notice of the tasks they would have to perform. To their horror, sometimes the Sonderkommando inductees would discover members of their own family amid the bodies.[4] They had no way to refuse or resign other than by committing suicide.[5] In some places and environments, the Sonderkommandos might be euphemistically connoted as Arbeitsjuden (Jews for work).[6] Other times, Sonderkommandos were called Hilflinge (helpers).[7] At Birkenau the Sonderkommandos or "special squads" reached up to 400 people by 1943, and when Hungarian Jews were deported there in 1944, their number swelled to over 900 persons to accommodate the increased rounds of murder and extermination.[8]

Because the Germans needed the Sonderkommandos to remain physically able, they were granted much less squalid living conditions than other inmates: they slept in their own barracks and were allowed to keep and use various goods such as food, medicines and cigarettes brought into camp by those who were sent to the gas chambers. Unlike ordinary inmates, they were not normally subject to arbitrary, random killing by guards. Their livelihood and utility was determined by how efficiently they could keep the Nazi death factory running.[9] As a result, Sonderkommando members tended to survive longer than other inmates of the death camps — but few survived the war.

Because of their intimate knowledge of the process of Nazi mass murder, the Sonderkommando were considered Geheimnisträger — bearers of secrets — and as such, they were kept in isolation from other camp inmates, except for those about to enter the gas chambers.[10] Since the Germans did not want Sonderkommandos' knowledge to reach the outside world, they followed a policy of regularly gassing almost all the Sonderkommando and replacing them with new arrivals at intervals of approximately 3 months and up to a year or more in some cases (special skills might merit longer life).[11] The first task of the new Sonderkommandos would be to dispose of their predecessors' corpses. Therefore, since the inception of the Sonderkommando through to the liquidation of the camp there existed approximately 14 generations of Sonderkommando victims.[12]

Revolts

In 1944, there was a revolt by Sonderkommandos at Auschwitz in which one of the crematoria was partly destroyed. For months, young Jewish women, like Ester Wajcblum, Ala Gertner, and Regina Safirsztain, had been smuggling gunpowder from the Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke, a munitions factory within the Auschwitz complex, to men and women in the camp's resistance movement, like Roza Robota, a young Jewish woman who worked in the clothing detail at Birkenau. Under constant guard, the women in the factory took small amounts of the gunpowder, wrapped it in bits of cloth or paper, hid it on their bodies, and then passed it along the smuggling chain. Once she received the gunpowder, Robota passed it to her co-conspirators in the Sonderkommando. Using this gunpowder, the leaders of the Sonderkommando planned to destroy the gas chambers and crematoria, and launch the uprising.[13]

When the camp resistance warned the Sonderkommando that they were due to be murdered on the morning of 7 October 1944, the Sonderkommando attacked the SS and Kapos with two machine guns, axes, knives and grenades. The SS men suffered 15 casualties[14] of whom about 12 were injured and 3 were killed;[15](A non SS Kapo was also killed in the uprising[16]) Some of the Sonderkommando escaped from the camp for a period, as was planned, but they were recaptured later the same day.[12] Of those who didn't die in the uprising itself, 200 were later forced to strip and lie face down, and then were shot in the back of the head. A total of 451 Sonderkommandos were killed on this day.[17][18][19]

There was also an uprising in Treblinka on 2 August 1943, in which around 100 prisoners succeeded in breaking out of the camp,[20] and a similar uprising in Sobibór on 14 October 1943.[21] The uprising in Sobibor was dramatized in the film Escape from Sobibor. The Sonderkommando in Sobibór's Camp III did not take part in the uprising in Camp I, but were murdered the following day.

Sobibor and Treblinka were closed shortly afterwards. Fewer than twenty out of several thousand members of the special squads are documented to have survived until liberation and were able to testify to the events (although some sources claim more[22]), among them: Henryk (Tauber) Fuchsbrunner, Filip Müller, Daniel Behnnamias, Dario Gabbai, Morris Venezia, Shlomo Venezia, Alter Fajnzylberg, Abram Dragon, David Olère, Henryk Mandelbaum, Martin Gray. There have been at most another six or seven confirmed to have survived, but who have not given witness (or at least, such testimony is not documented). Buried and hidden accounts by members of the Sonderkommando were also later found at some camps.

Testimonies

Between 1943 and 1944, some members of the Sonderkommando were able to obtain writing equipment and record some of their experiences and what they had witnessed in Birkenau. These documents were buried in the grounds of the crematoria and recovered after the war. Five men have been identified as the authors of these manuscripts: Zalman Gradowski, Zalman Lewental, Leib Langfus, Chaim Herman and Marcel Nadjary. The first three wrote in Yiddish, Herman in French and Nadjary in Greek. The manuscripts are mostly kept in the archive of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Memorial Museum, apart from Herman’s letter (kept in the archives of the Amicale des déportés d’Auschwitz-Birkenau) and Gradowski’s texts, one of which is held in the Medical Military Museum in St Petersburg, and another in Yad Vashem.[23] Some of the manuscripts were published as The Scrolls of Auschwitz, edited by Ber Mark.[24] The Auschwitz Museum published some others as Amidst a Nightmare of Crime.[25]

The Scrolls of Auschwitz have been recognised as some of the most important testimony to be written about the Holocaust, as they include contemporaneous eye-witness accounts of the workings of the gas chambers in Birkenau.[26]

The following note was found buried in the Auschwitz crematoria and was written by Zalman Gradowski, a member of the Sonderkommando who was killed in the 7 October 1944 revolt:

"Dear finder of these notes, I have one request of you, which is, in fact, the practical objective for my writing ... that my days of Hell, that my hopeless tomorrow will find a purpose in the future. I am transmitting only a part of what happened in the Birkenau-Auschwitz Hell. You will realize what reality looked like ... From all this you will have a picture of how our people perished."[27]

Controversies: History, literature, and film

This section possibly contains original research. (March 2016) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

Seen as relatively privileged prisoners working alongside the Germans to keep the process of mass-murder running smoothly, the Sonderkommando were always a subject of considerable controversy. Other prisoners often viewed them as collaborators; and many Sonderkommando members themselves felt similarly, even though they were aware that they had been forced into the job and had no way to avoid it other than suicide. Accusations of collaboration have persisted in some quarters; but over time it has become clear that in fact the Sonderkommando did not serve by choice. The horrors and moral dilemmas faced by the Sonderkommando has been the subject of many historians, authors, and cinematographers.

The earliest portrayals of the Sonderkommando were generally unflattering. Miklos Nyiszli, in Auschwitz: A Doctor’s Eyewitness Account, described the Sonderkommando as enjoying a virtual feast, complete with chandeliers and candlelight, as other prisoners died of starvation. Nyiszli, an admitted collaborator who assisted Dr. Josef Mengele in his medical experiments on Auschwitz prisoners, would appear to have been in a good position to observe the Sonderkommando in action, as he had an office in Krematorium II; and yet, the significant inaccuracy of some of his physical descriptions of the crematoria diminishes his credibility in this regard. Historian Gideon Greif characterized Nyiszli’s writings as among the “myths and other wrong and defamatory accounts” of the Sonderkommando that flourished in the absence of first-hand testimony by surviving Sonderkommando members.[28]

Primo Levi, in The Drowned and the Saved, characterizes the Sonderkommando as being a step away from collaborators. Nevertheless, he asks his readers to refrain from condemnation: “Therefore I ask that we meditate upon the story of ‘the crematorium ravens’ with pity and rigor, but that judgment of them be suspended.” [29] Levi, whose time at Auschwitz was spent at Camp III/Monowitz (a.k.a. the Buna Werke), may not have directly encountered the Sonderkommando. It has been said that he could have based his description of them on Nyiszli.

Filip Müller was one of the few Sonderkommando members who survived the war, and was also unusual in that he served on the Sonderkommando far longer than most. He wrote of his experiences in his 1979 book Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers.[30] Among other incidents he related, Müller recounted how he tried to enter the gas chamber to die with a group of his countrymen, but was dissuaded from suicide by a girl who asked him to remain alive and bear witness.[31] In the last several years, several other more sympathetic accounts of the Sonderkommando have been published, beginning with Gideon Greif’s own book We Wept Without Tears, which consists of exhaustive, and sometimes grueling, interviews with former Sonderkommando members. Greif includes as his prologue the poem “And What Would You Have Done?” by Gunther Anders, which makes the point that one who has not been in that situation has little right to judge the Sonderkommando: “Not you, not me! We were not put to that ordeal!” [32]

The first theatre play to describe the Sonderkommando revolt was written in 1947 by Ludovic Bruckstein (born 1920, in Munkach, now Ukraine, and subsequently sent to the camps in May 1944, from Sighet). It was entitled "Nacht-Shicht", or Night-Shift in Yiddish, and played with great success by the Romanian Yiddish Theaters of Bucharest and Yasi, from 1948 till 1957.[33] It is available (in Yiddish) on the internet.

A theatre play that explores the moral dilemmas of the Sonderkommando was the “The Grey Zone”, directed by Doug Hughes and produced in New York at MCC Theater in 1996.[34] The play was later made into a film of the same title by producer Tim Blake Nelson.[35] The film[36] took its mood, as well as much of its plot, from Nyiszli, portraying members of the Sonderkommando as crossing the line from victim to perpetrator, as when Sonderkommando Hoffman (played by David Arquette) beats a man to death in the undressing room under the eyes of a smiling SS member. Nelson makes it clear that the subject of the film is that very moral ambiguity. “We can see each one of ourselves in that situation, perhaps acting in that way, because we are human. But we’re not sanctified victims.” [37]

A 2014 “novelized” memoir, A Damaged Mirror, explores the lengths to which a former Sonderkommando will go to obtain forgiveness and closure: “The fact that good people can be forced to do wrong doesn’t make them less good,” the survivor says of himself, “but it also doesn’t make the wrong less wrong.”[38]

In 2015, Son of Saul, a 2015 Hungarian film directed by László Nemes, and winner of the 2015 Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix, details the story of one Sonderkommando attempting to bury a dead child he takes for his son. Géza Röhrig, who starred in the film, reacted with anger to the suggestion, made by a journalist, that members of the Sonderkommando were “half-victim, half-hangman”. “There has to be a clarification,” he said. “They are 100% victims. They have not spilled blood or been involved in any sort of killing. They were inducted on arrival under the threat of death. They had no control of their destinies. They were as victimised as any other prisoners in Auschwitz.”.[39]

Gallery

See also

Notes

- ^ Friedländer (2009). Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1945, pp. 355-356.

- ^ Shirer (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 970.

- ^ Sofsky 1996, p. 267.

- ^ Sofsky 1996, p. 269.

- ^ Sofsky 1996, p. 271.

- ^ Sofsky 1996, p. 283.

- ^ Michael & Doerr (2002). Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi-German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich, p. 209.

- ^ Wachsmann & Caplan, eds. (2010) Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories, p. 73.

- ^ Sofsky 1996, p. 271-273.

- ^ Greif (2005). We Wept Without Tears: Interviews with Jewish Survivors of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando, p. 4.

- ^ Greif (2005). We Wept Without Tears: Interviews with Jewish Survivors of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando, p. 327.

- ^ a b Dr. Miklos Nyiszli (1993). Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-202-8.

- ^ "Auschwitz Revolt (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ reports that 70 SS were killed are apparently exaggerated Axis History forum

- ^ Rees, Laurence (2012). Auschwitz: The Nazis and the "Final Solution". Random House. p. 324.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Axis History Forum

- ^ Auschwitz, 1940-1945: Mass murder. Books.google.com. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Anatomy of the Auschwitz death camp. Books.google.com. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ We wept without tears: testimonies ... Books.google.com. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Chrostowski, Witold, Extermination Camp Treblinka, Vallentine Mitchell, Portland, OR, 2003, p. 94, ISBN 0-85303-457-5

- ^ Jules Schelvis (2007). Sobibor. A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Berg, Oxford & New York. ISBN 978-1-84520-419-8.

- ^ "Auschwitz - Sonderkommando". Hagalil.com. 2 May 2000. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Chare, Nicholas (2011) Auschwitz and Afterimages: Abjection, Witnessing and Representation. London: IB Tauris; Stone, Dan (2013) ‘The Harmony of Barbarism: Locating the Scrolls of Auschwitz in Holocaust Historiography’. In Representing Auschwitz: At the Margins of Testimony, eds Nicholas Chare and Dominic Williams. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 11–32.

- ^ Mark, Ber. (1985) The Scrolls of Auschwitz. Trans. Sharon Neemani. Tel Aviv: Am Oved.

- ^ Bezwińska, Jadwiga, and Danuta Czech (1973) Amidst a Nightmare of Crime: Manuscripts of Members of Sonderkommando. Trans. Krystyna Michalik. Oświęcim: State Museum at Oświęcim.

- ^ Stone, (2013)

- ^ Rutta, Matt Yad Vashem website, Rabbinic Rambling, 23 March 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Gideon Greif and Andreas Kilian, “Significance, responsibility, challenge: Interviewing the Sonderkommando survivors” Sonderkommando-Studien, April 7, 2004, <http://www.sonderkommando-studien.dt/artikel.php?c=forschung/significance> (September 19, 2008).]

- ^ Primo Levi, The Drowned and The Saved (New York: Vintage International, 1989), 60.

- ^ Müller, Filip (1999) [1979]. 'Eyewitness Auschwitz - Three Years in the Gas Chambers. trans. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. and Susanne Flatauer. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee & in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 180. ISBN 1-56663-271-4.

- ^ Müller, 1979, p. 113.

- ^ http://websrv-cluster-ip8.its.yale.edu/yupbooks/excerpts/greif_wept.pdf

- '^ Petrescu, Corina L. (2011) “The People of Israel Lives!” Performing the Shoah on Post-War Bucharest’s Yiddish Stages.' In: Jeanine Teodorescu and Valentina Glajar (eds) Local History, Transnational Memory in the Romanian Holocaust. Basingstoke: Palgrave. 209-223.

- ^ Kristin Hohenadel, “FILM; A Holocaust Horror Story Without A Schindler,” The New York Times , January 7, 2001, sec. Movies, http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/07/movies/film-a-holocaust-horror-story-without-a-schindler.html.

- ^ Patrick Henry, “The Grey Zone,” Philosophy and Literature 33, no. 1 (2009): 159. Cited in Nicole Meehan, “An unrepresentable concept? Tim Blake Nelson’s “The Grey Zone” in Theatre and Film”. Accessed 28 May 2015

- ^ (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0252480/)

- ^ http://www.aboutfilm.com/features/greyzone/feature.htm#links

- ^ A Damaged Mirror: A story of memory and redemption. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/15/son-of-sauls-astonishing-recreation-of-auschwitz-renews-holocaust-debate

References

- Chare, Nicholas, and Williams, Dominic. (2016) Matters of Testimony: Interpreting the Scrolls of Auschwitz. New York: Berghahn.

- Friedländer, Saul. (2009). Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1945. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Greif, Gideon (2005). We Wept Without Tears: Interviews with Jewish Survivors of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Michael, Robert, and Doerr, Karin (2002). Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi-German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich. Westport, CT, USA: Greenwood Press.

- Shirer, William L. (1990)[1961]. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: MJF Books.

- Sofsky, Wolfgang (2013) [1996]. The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp (Google Book, preview). Princeton, NJ, United States: Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400822181.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus, and Jane Caplan, eds. (2010). Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. New York: Routledge.

- Eyewitness accounts from members of the Sonderkommando. Publications include:

- Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers, deposition by Henryk Tauber in the Polish Courts, May 24, 1945, p. 481–502, Jean-Claude Pressac, Pressac-Klarsfeld, 1989, The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, New York, Library of Congress 89-81305

- Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers by Filip Müller, Ivan R. Dee, 1979, ISBN 1-56663-271-4

- We Wept Without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz by Gideon Greif, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10651-3.

- The Holocaust Odyssey of Daniel Bennahmias, Sonderkommando by Rebecca Fromer, University Alabama Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8173-5041-1.

- Auschwitz : A Doctor's Eyewitness Account by Miklós Nyiszli (translated from the original Hungarian), Arcade Publishing, 1993, ISBN 1-55970-202-8. A play and subsequent film about the Sonderkommandos, The Grey Zone (2001) directed by Tim Blake Nelson, was based on this book.

- Dario Gabbai (Interview Code 142, conducted in English) video testimony, interview conducted in November 1996, Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, USC Shoah Foundation Institute, University of Southern California.

- Sonderkommando Auschwitz. La verità sulle camere a gas. Una testimonianza unica, Shlomo Venezia, Rizzoli, 2007, ISBN 88-17-01778-7

- Sonder. An Interview with Sonderkommando Member Henryk Mandelbaum, Jan Południak, Oświęcim, 2008, ISBN 978-83-921567-3-4

- History of the Jüdische Sonderkommando Sonderkommando-studien.de (further content: Zum Begriff Sonderkommando und verwandten Bezeichnungen • „Handlungsräume“ im Sonderkommando Auschwitz. • Der „Sonderkommando-Aufstand“ in Auschwitz-Birkenau – Photos )

- Informations about Auschwitz Sonderkommandos members, French website Sonderkommando.info