Strepsiptera

| Strepsiptera Temporal range: Middle Cretaceous - Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| male | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | Strepsiptera Kirby, 1813

|

| Families | |

|

Mengenillidae | |

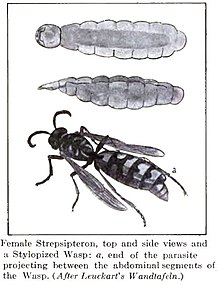

The Strepsiptera (known in older literature as twisted-winged parasites) are an order of insects with nine families making up about 600 species. The early stage larvae and the short-lived adult males are free-living but most of their life is spent as endoparasites in other insects such as bees, wasps, leafhoppers, silverfish, and cockroaches.[1]

Appearance and biology

Male Strepsiptera have wings, legs, eyes, and antennae, and look like flies, though they generally have no useful mouthparts. Many of their mouth parts are modified into sensory structures. Adult males are very short-lived (usually less than five hours) and do not feed. Females, in all families except the Mengenillidae, never leave their hosts and are neotenic in form, lacking wings and legs. Virgin females release a pheromone which the males search for. In the Stylopidia the female has its anterior region extruding out of the host body and the male mates by rupturing the female's brood canal opening which lies between the head and prothorax. Sperm passes through the opening in a process termed hypodermic insemination.[1] Each female produces many thousands of triungulin larvae that emerge from the brood opening on the head, which protrudes outside the host body. These larvae have legs (which lack trochanters) and actively search out new hosts.[2] Their hosts include members belonging to the orders Zygentoma, Orthoptera, Blattodea, Mantodea, Heteroptera, Hymenoptera, and Diptera. In the Strepsipteran family Myrmecolacidae, the males parasitize ants while the females parasitize Orthoptera.[1]

Suggested phylogenetic position of the Strepsiptera.[3] |

Strepsiptera eggs hatch inside the female and the planidium larvae can move around freely within the female's haemocoel, which is unique to these animals. The female has a brood canal that communicates with the outside world and it is through this the larvae escape.[4] The larvae are very active, as they only have a limited amount of time to find a host before they exhaust their food reserves. These first-instar larvae have stemmata (simple, single-lens eyes) and once they latch onto a host they enter it by secreting enzymes that soften the cuticle, usually in the abdominal region of the host. Some species have been reported to enter the eggs of hosts. Larvae of Stichotrema dallatorreanurn Hofeneder from Papua New Guinea were found to enter their orthopteran host's tarsus (foot).[5] Once inside the host, they undergo hypermetamorphosis and become a less mobile legless larval form. They induce the host to produce a bag like structure inside which they feed and grow. This structure, made from host tissue, protects them from the immune defences of the host. Larvae go through four more instars and in each moult there is separation of the older cuticle but no discarding ("apolysis without ecdysis") leading to multiple layers being formed around the larvae.[6] Male larvae produce pupae after the last moult, but females directly become neotenous adults.[7][8] The colour and shape of the host's abdomen may be changed and the host usually becomes sterile. The parasites then undergo holometabolous metamorphosis to become adults. Adult males emerge out of the host body while females stay inside. Females may occupy up to 90% of the abdominal volume of their hosts.[1]

Male Strepsiptera have eyes unlike those of any other insect, resembling the schizochroal eyes found in the trilobite group known as Phacopida. Instead of a compound eye consisting of hundreds of ommatidia, each with a large lens and capable of producing a partial image, the strepsipteran eyes consist of only a few dozen ommatidia separated by cuticle and/or setae, giving the eye a blackberry-like appearance.[1][9]

Multiple females may be seen within a stylopized host. Males are rarely seen. They may sometimes be seen at light traps or may be lured using cages containing virgin females.[1]

Strepsiptera may alter the behaviour of their hosts. Myrmecolacids may cause their ant hosts to climb up the tips of grass leaves, possibly to increase the spread of female pheromones to increase the chances of being located by males.[10]

Classification

The order, named by William Kirby in 1813, is named for the hind wings (strepsi=twisted + ptera=wing), which are held at a twisted angle when at rest. The forewings are reduced to halteres (and initially thought to be dried and twisted).

Strepsiptera are an enigma to taxonomists. Originally it was believed they were the sister group to the beetle families Meloidae and Ripiphoridae, which have similar parasitic development and forewing reduction; early molecular research suggested their inclusion as a sister group to the flies,[1] in a clade called the halteria[11] which have one pair of the wings modified into halteres[12], and failed to support their relationship to the beetles.[12] More recent molecular studies, however, suggest that they are outside the clade Mecopterida (containing the Diptera and Lepidoptera), yet there is no strong evidence for affinity with any other extant group.[13] Study of their evolutionary position has been problematic due to difficulties in phylogenetic analysis arising from long branch attraction.[14] The oldest known strepsipteran is Cretostylops engeli discovered in middle Cretaceous amber from Myanmar.

Families

The Strepsiptera have two major groups Stylopidia and Mengenillidia. The Mengenillidia include the extinct family Mengeidae and one extant family Mengenillidae. They are considered more primitive and the females are free living, with rudimentary legs and antennae. The females have a single genital opening. The males have strong mandibles.[1]

The other group, Stylopidia, includes seven families Corioxenidae, Halictophagidae, Callipharixenidae, Bohartillidae, Elenchidae, Myrmecolacidae, and Stylopidae. All Stylopidia have endoparasitic females having multiple genital openings.[1]

Stylopidae have 4 segmented tarsi and 4-6 segmented antennae with the third segment having a lateral process. The family Stylopidae may be paraphyletic.[1] The Elenchidae have 2-segmented tarsi and 4 segmented antennae with the third segment having a lateral process. The Halictophagidae have 3-segmented tarsi and 7-segmented antennae with lateral processes from the third and fourth segments.[2] The Stylopidae mostly parasitize wasps and bees, the Elenchidae are known to parasitize Fulgoroidea while the Halictophagidae are found on leafhoppers, treehoppers as well as mole cricket hosts.[2]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Whiting, M. F in Resh, V. H. & R. T. Cardé (Editors) 2003. Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 1094-1096

- ^ a b c Borror, D.J., Triplehorn, C.A. Johnson. ( 1989) Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th ed. Brooks Cole.

- ^ Kathirithamby, Jeyaraney. 2002. Strepsiptera. Twisted-wing parasites. Version 24 September 2002. [1] in The Tree of Life Web Project

- ^ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- ^ Kathirithamby, Jeyaraney (2001) Stand Tall and They Still Get You in Your Achilles Foot-Pad. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 268(1483):2287-2289.

- ^ Kathirithamby, Jeyaraney; Larry D. Ross; J. Spencer Johnston (2003) Masquerading as Self? Endoparasitic Strepsiptera (Insecta) Enclose Themselves in Host-Derived Epidermal Bag. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100(13):7655-7659.

- ^ Beani, Laura (2006) Crazy wasps: when parasites manipulate the Polistes phenotype. Ann. Zool. Fennici 43:564-574 PDF

- ^ Kathirithamby, J (2000) Morphology of the female Myrmecolacidae (Strepsiptera) including the apron, and an associated structure analogous to the peritrophic matrix. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 128:269-287

- ^ Buschbeck,E. K.,B. Ehmer, R. R. Hoy (2003) The unusual visual system of the Strepsiptera: external eye and neuropils. J. Comp. Physiol. A 189:617–630 DOI 10.1007/s00359-003-0443-x PDF

- ^ Wojcik, Daniel P. (1989) Behavioral Interactions between Ants and Their Parasites. The Florida Entomologist. 72(1):43-51.

- ^ Michael F. Whiting (1998) Long-Branch Distraction and the Strepsiptera. Systematic Biology 47(1):134-138. PDF

- ^ a b Whiting, Michael F.; James C. Carpenter; Quentin D. Wheeler; Ward C. Wheeler (1997) The Stresiptera Problem: Phylogeny of the Holometabolous Insect Orders Inferred from 18S and 28S Ribosomal DNA Sequences and Morphology. Systematic Biology. 46(1):1-68.

- ^ Bonneton, F.; F. G. Brunet; J. Kathirithamby and V. Laudet (2006) The rapid divergence of the ecdysone receptor is a synapomorphy for Mecopterida that clarifies the Strepsiptera problem. Insect Molecular Biology 15(3):351-362.

- ^ Huelsenbeck, John P. (1998) Systematic Bias in Phylogenetic Analysis: Is the Strepsiptera Problem Solved? Systematic Biology. 47(3):519-537.

References

- Grimaldi, D. and Engel, M.S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82149-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)