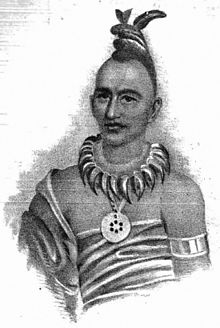

Taimah

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2015) |

Taimah (1790-1830; var. Taiomah, Tama, Taima, Tiamah, Fai-inah, Ty-ee-ma, lit. "sudden crash of thunder" or "thunder") was a Meskwaki (Fox) leader in the early 19th century in present-day Wisconsin, Iowa and Illinois. He was often called Chief Tama in historical accounts and was one of the signatories of an 1824 treaty in Washington, DC ceding land to the United States.

Life

Taimah was born into a Meskwaki family in their historic territory in present-day Wisconsin. His name was spelled by many variations in historic records. Ty-ee-ma in Meskwaki means "sudden crash of thunder" or "thunder." He grew up in the Meskwaki culture, when they came under increasing pressure from United States encroachment. He became noted among Americans for saving the life of the United States Indian agent at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, by warning him of an assassination attempt. The Meskwaki had long occupied territory around the Great Lakes, in Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois, moving into Iowa.

After the Meskwaki migrated from Wisconsin, Taimah became the principal leader of one of their villages near what later developed as Burlington, Iowa. He also maintained a village near Gladstone, Illinois in the 1820s.[1] Caleb Atwater mistakenly credited Taimah with being the leader of Quashquame's village, but he was this chief's son-in-law.[2]

In 1820 Taimah was interviewed by Jedidiah Morse at Fort Armstrong in Illinois. Morse was gathering information from tribes as an agent for the US Department of War, which then had jurisdiction over Native Americans. Morse wrote of Taimah:

The second chief of this [Meskwaki] nation is Ty-ee-ma... about forty years old. This man appears to be more intelligent than any other to be found either among the Foxes or Sauks; but he is extremely unwilling to communicate anything relative to the history manners and customs of his people. He has a variety of maps of different parts of the world and appears to be desirous of gaining geographical information.... He one day informed me when conversing upon this subject that the Great Spirit had put Indians on the earth to hunt, and gain a living in the wilderness; that he always found, that when any of their people departed from this mode of life, by attempting to learn to read write and live as white people do, the Great Spirit was displeased, and they soon died; he concluded, by observing, that when the Great Spirit made them, he gave them their medicine-bag, and they intended to keep it.

— Jedidiah Morse (1822), A Report to the Secretary of War of the United States, on Indian Affairs: Comprising a Narrative of a Tour Performed in the Summer of 1820

Taimah signed the 1824 treaty in Washington, DC by which the Meskwaki ceded much of their land in Wisconsin to the United States.[3]

He died in 1830. Taimah is buried near what developed as Kingston, about 1/4 mile from the Mississippi River, in a small patch of land in the middle of a corn field. A stone bearing his name is located about 20 rods west. Never having been plowed, this land is covered in trees, and foliage. The gravesite is on private property, and is not open to visitors. Des Moines County Highway 99 runs near this site.

Legacy

- He was the namesake of the city of Tama, and Tama County, Iowa. The city is located near the Meskwaki Settlement, founded in 1857 when the Meskwaki were allowed to buy land in the state.

Taimah's son was Appanoose;[4] he also became a chief. Appanoose County, Iowa was named for him.