Taking Sides (film)

| Taking Sides | |

|---|---|

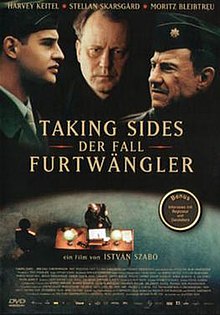

German film poster | |

| Directed by | István Szabó |

| Written by | Ronald Harwood |

| Produced by | Yves Pasquier |

| Starring | Harvey Keitel Stellan Skarsgård Moritz Bleibtreu Birgit Minichmayr Ulrich Tukur Oleg Tabakov R. Lee Ermey |

| Cinematography | Lajos Koltai |

| Edited by | Sylvie Landra |

Release dates | 13 September 2001 (Toronto International Film Festival) 16 February 2002 (Germany) 30 April 2002 (France) 5 September 2003 (US) 21 November 2003 (UK) |

| Countries | |

| Languages | English (UK/US version) German and English (international version) |

Taking Sides (German title Taking Sides - Der Fall Furtwängler) is a 2001 German-French-Austrian-British[1] co-production directed by István Szabó and starring Harvey Keitel and Stellan Skarsgård. The story is set during the period of denazification investigations conducted in post-war Germany after the Second World War, and it is based on the real interrogations that took place between a U.S. Army investigator and the musical conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had been charged with serving the Nazi regime. It is based on the 1995 play of the same title by Ronald Harwood.

The film was shot on location in Germany with the dialogue in German and English, although in the version released in the US and the UK the dialogue is only in English.

Plot

In Berlin at the end of World War II, Wilhelm Furtwängler (Stellan Skarsgård) is conducting Beethoven's 5th Symphony when yet another Allied bomb raid stops the performance. A minister in Hitler's government comes to Furtwängler's dressing room to advise him that he should go abroad, and escape the war. The film then jumps to some time after the Allied victory, and we see U.S. Army General Wallace (R. Lee Ermey) task Major Steve Arnold (Harvey Keitel) with "getting" Furtwängler at his denazification hearing: "Find Wilhelm Furtwängler guilty. He represents everything that was rotten in Germany".[2]

Arnold gets an office with Lt. David Wills (Moritz Bleibtreu), a German-American Jew, and Emmaline Straube (Birgit Minichmayr), daughter of an executed member of the German resistance. Arnold questions several musicians, many of whom know Emmaline's father and say that Furtwängler refused to give Hitler the Nazi salute.

Arnold begins interrogating Furtwängler, asking why he didn't leave Germany in 1933 like so many other musicians? Why he played for Hitler's birthday? Why he played at a Nazi rally? And why his recording of Anton Bruckner's 7th Symphony was used on the radio after Hitler's death? Arnold gets a second violinist to tell him about Furtwängler's womanizing and the conductor's professional jealousy of Herbert von Karajan.

In a sub plot, Arnold is assisted by a young Jewish lieutenant from the Big Red One. The young officer begins to have sympathy for the conductor as well as for the young German girl who works as a clerk in their office. This causes friction between Arnold and his job investigating former suspected Nazis.

In a voice-over, Arnold explains that Furtwängler was exonerated at the later hearings but boasts that his questioning "winged" him. Actual footage of the real Furtwängler shows him shaking hands with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels after a concert. The conductor surreptitiously wipes his hands with a cloth after touching the Nazi.

Cast

- Harvey Keitel as Major Steve Arnold

- Stellan Skarsgård as Wilhelm Furtwängler

- Moritz Bleibtreu as Lieutenant David Wills

- Birgit Minichmayr as Emmi Straube

- Ulrich Tukur as Helmut Alfred Rode, 2nd violinist

- Oleg Tabakov as Colonel Dymshitz

- Hanns Zischler as Rudolf Otto Werner, oboist

- Armin Rohde as Schlee, timpanist

- R. Lee Ermey as General Wallace

- August Zirner as Captain Ed Martin

- Daniel White as Sergeant Adams

- Thomas Thieme as Reichsminister

- Frank Leboeuf as French aide

Historical basis

Even though many prominent contemporary German artists left, Furtwängler did not leave Germany in 1933 after Adolf Hitler took power. He played at numerous concerts attended by Nazi officials. A recording of the Adagio of Bruckner's Seventh Symphony was even played after the announcement of the death of Hitler. In 1945, he eventually went to Switzerland after playing a concert in Vienna. These facts, compounded by circumstances of the denazification hearings, caused Furtwängler's case to be significantly delayed.[3]

Furtwängler was specifically charged with supporting Nazism by remaining in Germany, performing at Nazi party functions and with making an anti-Semitic remark against the part-Jewish conductor Victor de Sabata.[4] He was eventually cleared on all these counts.[5]

Reception

Roger Ebert found the movie "both interesting and unsatisfying. The Keitel performance is over the top, inviting us to side with Furtwängler simply because his interrogator is so vile. There are maddening lapses, as when Furtwängler's rescue of Jewish musicians is mentioned but never really made clear. But Skarsgård's performance is poignant; it has a kind of exhausted passivity, suggesting a man who once stood astride the world and now counts himself lucky to be insulted by the likes of Major Arnold."[6]

Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle finds that the movie's promise to provide a balanced argument "goes unrealized, and all we're left with is the spectacle of an idiot bullying a genius. Harvey Keitel's performance as the smug, self-satisfied major is terribly miscalculated, unless he intended for us to loathe the spectacle of a small, stupid man glorying in his sudden power. That's possible. Stellan Skarsgård plays Furtwängler with an air of exhaustion that seems a generous attempt to justify the script's weakness, that the conductor doesn't defend himself vigorously enough. Of the two men, it's the major who acts more like a Nazi."[7]

References

- ^ IMDb company credits Retrieved 2011-09-07

- ^ From film audio, 6 minutes into the film.

- ^ p. 154, Monod (2005) David. Chapel Hill Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans University of North Carolina Press

- ^ Monod, David (2005). Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945-1953. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-8078-2944-7.

- ^ Roger Smithson (1997). "Furtwängler's Silent Years: 1945-47" (.RTF). Société Wilhelm Furtwängler. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Taking Sides". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Winn, Steven; Guthmann, Edward; LaSalle, Mick; Johnson, G. Allen (2 September 2010). "FILM CLIPS / Also opening today". The San Francisco Chronicle.