Ted Shawn

Ted Shawn | |

|---|---|

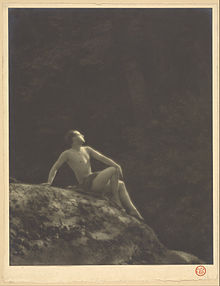

Ted Shawn, c. 1918, photographed by Arthur F. Kales | |

| Born | Edwin Myers Shawn October 21, 1891 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | January 9, 1972 (aged 80) |

| Occupation | Dancer |

Ted Shawn (21 October 1891 – 9 January 1972), originally Edwin Myers Shawn, was one of the first notable male pioneers of American modern dance. Along with creating Denishawn with former wife Ruth St. Denis he is also responsible for the creation of the well known all-male company Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers. With his innovative ideas of masculine movement, he is one of the most influential choreographers and dancers of his day. He is also the founder and creator of Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival in Massachusetts, and "was knighted by the King of Denmark for his efforts on behalf of the Royal Danish Ballet".[1]

Ted Shawn and the creation of Denishawn

Ted Shawn was born in Kansas City, Missouri on October 21, 1891.[2] Originally intending to become a minister of religion, he attended the University of Denver. There he caught diphtheria, and during his physical therapy was introduced to dance in 1910 to regain his muscle strength. Shawn's dancing was discouraged by the University, which still had a Methodist affiliation, and was the cause of his expulsion the following year.

Shawn did not realize his true potential as an artist until marrying Ruth St. Denis on August 13, 1914.[3] St. Denis served not only as partner but an extremely valuable creative outlet to Shawn. Soon after their marriage the couple opened the first Denishawn School in Los Angeles, California, where they were able to choreograph and stage many of their famous vaudeville pieces.[4] A very famous piece of advice that Shawn used to give to his dancers was "When in doubt, twirl."[5][6]

The following year, Shawn launched a cross-country tour with his dance partner, Norma Gould, and their Interpretive Dancers. Notable performances choreographed by him during Denishawn's 17-year run include Julnar of the Sea, Xochitl and Les Mysteres Dionysiaques.[7] The school and company went on to produce such influential dancers as Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman.[8]

Style and technique

Together, Shawn and Ruth St. Denis established the principle of Music Visualization in modern dance – a concept that called for movement equivalents to the timbres, dynamics, and structural shapes of music in addition to its rhythmic base. also he did ballet abd contempary

Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers

I believe that dance communicates man's deepest, highest and most truly spiritual thoughts and emotions far better than words, spoken or written.

— attributed to Ted Shawn,

in Outback and Beyond[9]

Due to marital problems of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn and financial difficulties, Denishawn concluded in 1929. Consequently, Shawn went on to form an all-male dance company, made up of athletes he taught at Springfield College in Massachusetts. Shawn's mission in creating this company was to fight for acceptance of the American male dancer and to bring awareness of the art form from a male perspective.[citation needed]

The all-male company was based out of a farm that Shawn purchased near his hometown Lee, Massachusetts. On July 14, 1933, Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers had their premier performance at Shawn's farm, which would later be known as Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival. Shawn produced some of his most innovate and controversial choreography to date with this company such as "Ponca Indian Dance", "Sinhalse Devil Dance", "Maori War Haka", "Hopi Indian Eagle Dance", "Dyak Spear Dances", and "Kinetic Molpai". Through these creative works Shawn showcased athletic and masculine movement that soon would gain popularity. The company performed in the United States and Canada, touring more than 750 cities, in addition to international success in London and Havana. Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers concluded at Jacob's Pillow on August 31, 1940 with a homecoming performance.

During the years of the company, Shawn's love for the relationships created by the men in his dances soon translated into love between himself and one of his company members, Barton Mumaw (1912–2001), which lasted from 1931 to 1948. One of the leading stars of the company, Barton Mumaw would emerge onto the dance industry and be considered "the American Nijinsky." While with Shawn, Mumaw began a relationship with a John Christian, a stage manager for the company. Mumaw introduced Shawn to Christian. Later, Shawn formed a partnership with John Christian, with whom he stayed from 1949 until his death in 1972.[10]

Jacob's Pillow

With this new company came the creation of Jacob's Pillow: a dance school, retreat, and theater. The facilities also hosted teas, which, over time, became the Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival.[11][12] Shawn also created The School of Dance for Men around this time, which helped promote male dance in colleges nationwide.

Shawn taught classes at Jacob's Pillow just months before his death at the age of 80.[13] In 1965, Shawn was a Heritage Award recipient of the National Dance Association. Shawn's final appearance on stage in the Ted Shawn Theater at Jacob's Pillow was in Siddhas of the Upper Air, where he reunited with St. Denis for their fiftieth anniversary.

Saratoga Springs is now the home of the National Museum of Dance, the United States' only museum dedicated to professional dance. Shawn was inducted into the museum's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in 1987.

Writings

Ted Shawn wrote and published nine books that provided a foundation for Modern Dance:[14]

- 1920 – Ruth St. Denis: Pioneer and Prophet

- 1926 – The American Ballet

- 1929 – Gods Who Dance

- 1935 – Fundamentals of a Dance Education

- 1940 – Dance We Must

- 1944 – How Beautiful Upon the Mountain

- 1954 – Every Little Movement: a Book About Francois Delsarte

- 1959 – Thirty-three Years of American Dance

- 1960 – One Thousand and One Night Stands (autobiography, with Gray Poole)

Legacy

In the 1940s, Shawn gifted his works to the Museum of Modern Art. The museum subsequently deaccessed these works, giving them to New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and Jacob's Pillow archive, while Shawn was still alive. Dancer Adam Weinert saw this as a violation of MoMA's policy not to sell or give away works by living artists, and created The Reaccession of Ted Shawn, digital, augmented reality performances of Shawn's works to be displayed in MoMA.[15][16]

References

- ^ "Ted Shawn". Jacob's Pillow Dance, jacobspillow.org. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Birth data: Astrodatabank

- ^ Schlundt 1998, p. 583

- ^ Benbow-Niemer 1998, p. 716

- ^ Schiff, Stephen (November 9, 1992). "Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense". The New Yorker: 94.

You know, Ted Shawn, the choreographer—he used to say, 'When in doubt, twirl.' Oh, I do think that's such a great line.

- ^ Haymes, Greg (November 11, 1994). "Ex-maniac Natalie Merchant's Mesmerizing Vocals Hypnotic as Ever". Albany Knickerbocker News.

- ^ Schlundt 1998, p. 585

- ^ Schlundt 1998, p. 584

- ^ Nolan, Cynthia (1994). Outback and Beyond. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 50, 51.

- ^ Foulkes 2002, pp. 85–86

- ^ Foulkes 2002, pp. 84–85

- ^ Cohen-Stratyner, Barbara N. (1982). Biographical Dictionary of Dance. New York: Schirmer Books. p. 811.

- ^ Benbow-Niemer 1998, p. 716

- ^ Kassing, Gayle. History of dance: an interactive arts approach. pp. 187–9.

- ^ Weinert, Adam. "The Reaccession of Ted Shawn". Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ Scherr, Apollinaire (August 19, 2014). "Downtown Dance Festival, Wagner Park, Lower Manhattan, New York". Financial Times. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

Further reading

- Dreier, Katherine S.; Hawkins, Ralph (1933). Shawn the Dancer. Berlin: Drei Masken Verlag.

- Terry, Walter (1976). Ted Shawn: The Father of Modern Dance. New York: Dial Press. ISBN 0-8037-8557-7.

- Shelton, Suzanne (1981). Divine Dancer: A Biography of Ruth St. Denis. New York: Doubleday.

- Jordan, Stephanie (1984). "Ted Shawn's Music Visualizations". Dance Chronicle. 7 (1).

- Bentivoglio, Leonetta (1985). Danza Contemporanea. Milan: Longanesi.

- Benbow-Niemer, Glynis (1998). "Shawn, Ted". In Benbow-Pfalzgraf, Taryn (ed.). International Dictionary of Modern Dance. Detroit: St. James Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foulkes, Julia L. (2002). Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism From Martha Graham to Alvin Ailey. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schlundt, Christena L. (1998). "Shawn, Ted". In Cohen, Selma J. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Dance. Vol. 5. New York: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Works by or about Ted Shawn at the Internet Archive

- Ted Shawn at IMDb

- "Shawn the Dancer". The Stowitts Museum & Library.

- Ted Shawn papers, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library

- Ted Shawn papers, Additions, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library

- Shawn, Ted (2005). Chaque petit mouvement: à propos de François Delsarte. Editions Complexe. ISBN 280480030X. ISSN 1761-1695.

- The Reaccession of Ted Shawn danced by Adam Weinert

Media

- Archive footage

- Ted Shawn's Men Dancers performing in Finale from The New World in 1936 at Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival

- Ted Shawn performing "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen" from Four Dances Based on American Folk Music in 1938 at Jacob's Pillow

- Ted Shawn's Men Dancers performing Kinetic Molpai in 1937 at Jacob's Pillow

- Jacob's Pillow Men Dancers rehearsing Kinetic Molpai with Barton Mumaw in 1992 at Jacob's Pillow

- Photographs

- Photograph of Ted Shawn by James Walter Collinge (10th picture in gallery)