Temporal bone

| Temporal bone | |

|---|---|

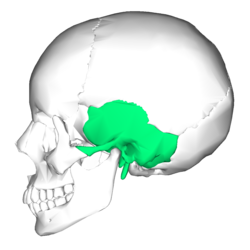

Position of temporal bone (shown in green) | |

Structure of temporal bone (left) | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Occipital, parietal, sphenoid, mandible and zygomatic |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Os temporale |

| MeSH | D013701 |

| TA98 | A02.1.06.001 |

| TA2 | 641 |

| FMA | 52737 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The temporal bones are situated at the sides and base of the skull, and lateral to the temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples and house the structures of the ears. The lower seven cranial nerves and the major vessels to and from the brain traverse the temporal bone.

Structure

The temporal bone consists of four parts[1][2]— the squamous, mastoid, petrous and tympanic parts. The squamous part is the largest and most superiorly positioned relative to the rest of the bone. The zygomatic process is a long, arched process projecting from the lower region of the squamous part and it articulates with the zygomatic bone. Posteroinferior to the squamous is the mastoid part. Fused with the squamous and mastoid parts and between the sphenoid and occipital bones lies the petrous part, which is shaped like a pyramid. The tympanic part is relatively small and lies inferior to the squamous part, anterior to the mastoid part, and superior to the styloid process. The styloid, from the Greek stylos, is a thorn shaped pillar directed inferiorly and anteromedially between the parotid gland and internal jugular vein.[3] An elongated or deviated styloid process can result from calcification of the stylohyoid ligament in a condition known as Eagle syndrome.

Borders

Development

The temporal bone is ossified from eight centers, exclusive of those for the internal ear and the tympanic ossicles: one for the squama including the zygomatic process, one for the tympanic part, four for the petrous and mastoid parts, and two for the styloid process. Just before the end of prenatal development [Fig. 6] the temporal bone consists of three principal parts:

- The squama is ossified in membrane from a single nucleus, which appears near the root of the zygomatic process about the second month.

- The petromastoid part is developed from four centers, which make their appearance in the cartilaginous ear capsule about the fifth or sixth month. One (proötic) appears in the neighborhood of the eminentia arcuata, spreads in front and above the internal auditory meatus and extends to the apex of the bone; it forms part of the cochlea, vestibule, superior semicircular canal, and medial wall of the tympanic cavity. A second (opisthotic) appears at the promontory on the medial wall of the tympanic cavity and surrounds the fenestra cochleæ; it forms the floor of the tympanic cavity and vestibule, surrounds the carotid canal, invests the lateral and lower part of the cochlea, and spreads medially below the internal auditory meatus. A third (pterotic) roofs in the tympanic cavity and antrum; while the fourth (epiotic) appears near the posterior semicircular canal and extends to form the mastoid process (Vrolik).

- The tympanic ring is an incomplete circle, in the concavity of which is a groove, the tympanic sulcus, for the attachment of the circumference of the eardrum (tympanic membrane). This ring expands to form the tympanic part, and is ossified in membrane from a single center which appears about the third month. The styloid process is developed from the proximal part of the cartilage of the second branchial or hyoid arch by two centers: one for the proximal part, the tympanohyal, appears before birth; the other, comprising the rest of the process, is named the stylohyal, and does not appear until after birth. The tympanic ring unites with the squama shortly before birth; the petromastoid part and squama join during the first year, and the tympanohyal portion of the styloid process about the same time [Fig. 7, 8]. The stylohyal does not unite with the rest of the bone until after puberty, and in some skulls never at all.

Postnatal development

Apart from size increase, the chief changes from birth through puberty in the temporal bone are as follows:

- The tympanic ring extends outward and backward to form the tympanic part. This extension does not, however, take place at an equal rate all around the circumference of the ring, but occurs more at its anterior and posterior portions. As these outgrowths meet, they create a foramen in the floor of the meatus, the foramen of Huschke. This foramen is usually closed about the fifth year, but may persist throughout life.

- The mandibular fossa is at first extremely shallow, and looks lateral and inferior; it deepens and directs more inferiorly over time. The part of the squama which forms the fossa lies at first below the level of the zygomatic process. As, the base of the skull thickens, this part of the squama is directed horizontal and inwards to contribute to the middle cranial fossa, and its surfaces look upward and downward; the attached portion of the zygomatic process everts and projects like a shelf at a right angle to the squama.

- The mastoid portion is at first flat, with the stylomastoid foramen and rudimentary styloid immediately behind the tympanic ring. With air cell development, the outer part of the mastoid component grows anteroinferiorly to form the mastoid process, with the styloid and stylomastoid foramen now on the under surface. The descent of the foramen is accompanied by a requisite lengthening of the facial canal.

- The downward and forward growth of the mastoid process also pushes forward the tympanic part; as a result, its portion that formed the original floor of the meatus, and contained the foramen of Huschke, rotates to become the anterior wall.

- The fossa subarcuata is nearly effaced.

-

1. Outer surface of petromastoid part. 2. Outer surface of tympanic ring. 3. Inner surface of squama.

-

Figure 7 : Temporal bone at birth. Outer aspect.

-

Figure 8 : Temporal bone at birth. Inner aspect.

Trauma

Temporal bone fractures were historically divided into three main categories, longitudinal, in which the vertical axis of the fracture paralleled the petrous ridge, horizontal, in which the axis of the fracture was perpendicular to the petrous ridge, and oblique, a mixed type with both longitudinal and horizontal components. Horizontal fractures were thought to be associated with injuries to the facial nerve, and longitudinal with injuries to the middle ear ossicles.[4] More recently, delineation based on disruption of the otic capsule has been found as more reliable in predicting complications such as facial nerve injury, sensorineural hearing loss, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea.[5]

Other animals

In many animals some of these parts stay separate through life:

- Squamosal: the squama including the zygomatic process

- Tympanic bone: the tympanic part: this is derived from the angular bone of the reptilian lower jaw

- Periotic bone: the petrous and mastoid parts

- Two parts of the hyoid arch: the styloid process. In the dog these small bones are called tympanohyal (upper) and stylohyal (lower).

In evolutionary terms, the temporal bone is derived from the fusion of many bones that are often separate in non-human mammals:

- The squamosal bone, which is homologous with the squama, and forms the side of the cranium in many bony fish and tetrapods. Primitively, it is a flattened plate-like bone, but in many animals it is narrower in form, for example, where it forms the boundary between the two temporal fenestrae of diapsid reptiles.[6]

- The petrous and mastoid parts of the temporal bone, which derive from the periotic bone, formed from the fusion of a number of bones surrounding the ear of reptiles. The delicate structure of the middle ear, unique to mammals, is generally not protected in marsupials, but in placentals, it is usually enclosed within a bony sheath called the auditory bulla. In many mammals this is a separate tympanic bone derived from the angular bone of the reptilian lower jaw, and, in some cases, it has an additional entotympanic bone. The auditory bulla is homologous with the tympanic part of the temporal bone.[6]

- Two parts of the hyoid arch: the styloid process. In the dog the styloid process is represented by a series of 4 articulating bones, from top down tympanohyal, stylohyal, epihyal, ceratohyal; the first two represent the styloid process, and the ceratohyal represents the anterior horns of the hyoid bone and articulates with the basihyal which represents the body of the hyoid bone.

Etymology

Its exact etymology is unknown.[7] It is thought to be from the Old French temporal meaning "earthly," which is directly from the Latin tempus meaning "time, proper time or season." Temporal bones are situated on the sides of the skull, where grey hairs usually appear early on. Or it may relate to the pulsations of the underlying superficial temporal artery, marking the time we have left here. There is also a probable connection with the Greek verb temnion, to wound in battle. The skull is thin in this area and presents a vulnerable area for a blow from a battle axe.[8]

Additional images

-

Position of temporal bone (green). Animation.

-

Shape of temporal bone (left).

-

Cranial bones.

-

Sphenoid and temporal bones

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 138 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 138 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "SKULL ANATOMY - TEMPORAL BONE".

- ^ Temporal bone anatomy on CT 2012-12-22

- ^ Chaurasia, BD. Human Anatomy Volume 3 (Sixth ed.). CBS Publishers and Distributors Pvt Ltd. pp. 41–43. ISBN 9788123923321.

- ^ Brodie, HA; Thompson, TC (March 1997). "Management of complications from 820 temporal bone fractures". The American journal of otology. 18 (2): 188–97. PMID 9093676.

- ^ Little, SC; Kesser, BW (December 2006). "Radiographic classification of temporal bone fractures: clinical predictability using a new system". Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 132 (12): 1300–4. doi:10.1001/archotol.132.12.1300. PMID 17178939.

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Colorado, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. XXX. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=temporal&searchmode=none

- ^ https://www.dartmouth.edu/~humananatomy/resources/etymology/Head.htm