The Bartered Bride

| The Bartered Bride | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Bedřich Smetana | |

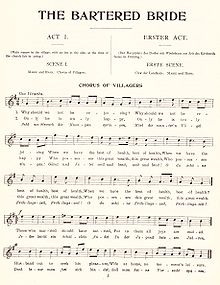

Cover of the score, 1919 | |

| Native title | [Prodaná nevěsta] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

| Librettist | Karel Sabina |

| Language | Czech |

| Premiere | 30 May 1866 Provisional Theatre, Prague |

The Bartered Bride (Czech: Prodaná nevěsta, The Sold Bride) is a comic opera in three acts by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana, to a libretto by Karel Sabina. The work is generally regarded as a major contribution towards the development of Czech music. It was composed during the period 1863–66, and first performed at the Provisional Theatre, Prague, on 30 May 1866 in a two-act format with spoken dialogue. Set in a country village and with realistic characters, it tells the story of how, after a late surprise revelation, true love prevails over the combined efforts of ambitious parents and a scheming marriage broker. The opera was not immediately successful, and was revised and extended in the following four years. In its final version, premiered in 1870, it gained rapid popularity and eventually became a worldwide success.

Czech national opera until this time had been represented only by a number of minor, rarely performed works. This opera, Smetana's second, was part of his quest to create a truly Czech operatic genre. Smetana's musical treatment made considerable use of traditional Bohemian dance forms such as the polka and furiant, although he largely avoided the direct quotation of folksong. He nevertheless created music which was accurately folk-like, and is considered by Czechs to be quintessentially Czech in spirit. The overture, often played as a concert piece independently from the opera, was, unusually, composed before almost any of the other music had been written.

After a performance at the Vienna Music and Theatre Exhibition of 1892, the opera achieved international recognition. It was performed in Chicago in 1893, London in 1895 and reached New York in 1909, subsequently becoming the first, and for many years the only, Czech opera in the general repertory. Many of these early international performances were in German, under the title Die verkaufte Braut, and the German-language version continues to be played and recorded. A German film of the opera was made in 1932 by Max Ophüls.[1]

Context

Until the middle 1850s Bedřich Smetana was known in Prague principally as a teacher, pianist and composer of salon pieces. His failure to achieve wider recognition in the Bohemian capital led him to depart in 1856 for Sweden, where he spent the next five years.[2] During this period he extended his compositional range to large-scale orchestral works in the descriptive style championed by Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner.[3] Liszt was Smetana's long-time mentor; he had accepted a dedication of the latter's Opus 1: Six Characteristic Pieces for Piano in 1848, and had encouraged the younger composer's career since then.[4] In September 1857 Smetana visited Liszt in Weimar, where he met Peter Cornelius, a follower of Liszt's who was working on a comic opera, Der Barbier von Bagdad.[5] Their discussions centred on the need to create a modern style of comic opera, as a counterbalance to Wagner's new form of music drama. A comment was made by the Viennese conductor Johann von Herbeck to the effect that Czechs were incapable of making music of their own, a remark which Smetana took to heart: "I swore there and then that no other than I should beget a native Czech music."[5]

Smetana did not act immediately on this aspiration. The announcement that a Provisional Theatre was to be opened in Prague, as a home for Czech opera and drama pending the building of a permanent National Theatre, influenced his decision to return permanently to his homeland in 1861.[6] He was then spurred to creative action by the announcement of a prize competition, sponsored by the Czech patriot Jan von Harrach, to provide suitable operas for the Provisional Theatre. By 1863 he had written The Brandenburgers in Bohemia to a libretto by the Czech nationalist poet Karel Sabina, whom Smetana had met briefly in 1848.[6][7] The Brandenburgers, which was awarded the opera prize, was a serious historical drama, but even before its completion Smetana was noting down themes for use in a future comic opera. By this time he had heard the music of Cornelius's Der Barbier, and was ready to try his own hand at the comic genre.[8]

Composition history

Libretto

For his libretto, Smetana again approached Sabina, who by 5 July 1863 had produced an untitled one-act sketch in German.[5] Over the following months Sabina was encouraged to develop this into a full-length text, and to provide a Czech translation. According to Smetana's biographer Brian Large, this process was prolonged and untidy; the manuscript shows amendments and additions in Smetana's own hand, and some pages apparently written by Smetana's wife Bettina (who may have been receiving dictation).[9] By the end of 1863 a two-act version, with around 20 musical numbers separated by spoken dialogue, had been assembled.[5][9] Smetana's diary indicates that he, rather than Sabina, chose the work's title because "the poet did not know what to call it."[9] The translation "Sold Bride" is strictly accurate, but the more euphonious "Bartered Bride" has been adopted throughout the English-speaking world.[10] Sabina evidently did not fully appreciate Smetana's intention to write a full-length opera, later commenting: "If I had suspected what Smetana would make of my operetta, I should have taken more pains and written him a better and more solid libretto."[5]

The Czech music specialist John Tyrrell has observed that, despite the casual way in which The Bartered Bride's libretto was put together, it has an intrinsic "Czechness", being one of the few in the Czech language written in trochees (a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one), matching the natural first-syllable emphasis in the Czech language.[11]

Composition

By October 1862, well before the arrival of any libretto or plot sketch, Smetana had noted down 16 bars which later became the theme of The Bartered Bride's opening chorus. In May 1863 he sketched eight bars which he eventually used in the love duet "Faithful love can't be marred", and later that summer, while still awaiting Sabina's revised libretto, he wrote the theme of the comic number "We'll make a pretty little thing".[5] He also produced a piano version of the entire overture, which was performed in a public concert on 18 November. In this, he departed from his normal practice of leaving the overture until last.[9]

The opera continued to be composed in a piecemeal fashion, as Sabina's libretto gradually took shape. Progress was slow, and was interrupted by other work. Smetana had become Chorus Master of the Hlahol Choral Society in 1862, and spent much time rehearsing and performing with the Society.[12] He was deeply involved in the 1864 Shakespeare Festival in Prague, conducting Berlioz's Romeo et Juliette and composing a festival march.[13] That same year he became music correspondent of the Czech language newspaper Národní listy. Smetana's diary for December 1864 records that he was continuing to work on The Bartered Bride; the piano score was completed by October 1865. It was then put aside so that the composer could concentrate on his third opera Dalibor.[14] Smetana evidently did not begin the orchestral scoring of The Bartered Bride until, following the successful performance of The Brandenburgers in January 1866, the management of the Provisional Theatre decided to stage the new opera during the following summer. The scoring was completed rapidly, between 20 February and 16 March.[14]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 30 May 1866[15] Conductor: Bedřich Smetana |

|---|---|---|

| Krušina, a peasant | Baritone | Josef Paleček |

| Ludmila, his wife | Soprano | Marie Procházková |

| Mařenka, their daughter | Soprano | Eleonora von Ehrenberg |

| Mícha, a landowner | Bass | Vojtěch Šebesta |

| Háta, his wife | Mezzo-soprano | Marie Pisařovicová |

| Vašek, their son | Tenor | Josef Kysela |

| Jeník, Mícha's son by a former marriage | Tenor | Jindřich Polák |

| Kecal, a marriage broker | Bass | František Hynek |

| Principál komediantů, Ringmaster | Tenor | Jindřich Mošna |

| Indián, an Indian comedian | Bass | Josef Křtín |

| Esmeralda, dancer and comedienne | Soprano | Terezie Ledererová |

Synopsis

Act 1

A crowd of villagers is celebrating at the church fair ("Let's rejoice and be merry"). Among them are Mařenka and Jeník. Mařenka is unhappy because her parents want her to marry someone she has never met. They will try to force her into this, she says. Her desires are for Jeník even though, as she explains in her aria "If I should ever learn", she knows nothing of his background. The couple then declare their feelings for each other in a passionate love duet ("Faithful love can't be marred").

As the pair leave separately, Mařenka's parents, Ludmila and Krušina, enter with the marriage broker Kecal. After some discussion, Kecal announces that he has found a groom for Mařenka – Vašek, younger son of Tobiáš Mícha, a wealthy landowner; the older son, he explains, is a worthless good-for-nothing. Kecal extols the virtues of Vašek ("He's a nice boy, well brought up"), as Mařenka re-enters. In the subsequent quartet she responds by saying that she already has a chosen lover. Send him packing, orders Kecal. The four argue, but little is resolved. Kecal decides he must convince Jeník to give up Mařenka, as the villagers return, singing and dancing a festive polka.

Act 2

The men of the village join in a rousing drinking song ("To beer!"), while Jeník and Kecal argue the merits, respectively, of love and money over beer. The women enter, and the whole group joins in dancing a furiant. Away from the jollity the nervous Vašek muses over his forthcoming marriage in a stuttering song ("My-my-my mother said to me"). Mařenka appears, and guesses immediately who he is, but does not reveal her own identity. Pretending to be someone else, she paints a picture of "Mařenka" as a treacherous deceiver. Vašek is easily fooled, and when Mařenka, in her false guise, pretends to woo him ("I know of a maiden fair"), he falls for her charms and swears to give Mařenka up.

Meanwhile, Kecal is attempting to buy Jeník off, and after some verbal fencing makes a straight cash offer: a hundred florins if Jeník will renounce Mařenka. Not enough, is the reply. When Kecal increases the offer to 300 florins, Jeník pretends to accept, but imposes a condition – no one but Mícha's son will be allowed to wed Mařenka. Kecal agrees, and rushes off to prepare the contract. Alone, Jeník ponders the deal he has apparently made to barter his beloved ("When you discover whom you've bought"), wondering how anyone could believe that he would really do this, and finally expressing his love for Mařenka.

Kecal summons the villagers to witness the contract he has made ("Come inside and listen to me"). He reads the terms: Mařenka is to marry no one but Mícha's son. Krušina and the crowd marvel at Jeník's apparent self-denial, but the mood changes when they learn that he has been paid off. The Act ends with Jenik being denounced by Krušina and the rest of the assembly as a rascal.

Act 3

Vašek expresses his confusions in a short, sad song ("I can't get it out of my head"), but is interrupted by the arrival of a travelling circus. The Ringmaster introduces the star attractions: Esmeralda, the Spanish dancer, a "real Indian" sword swallower, and a dancing bear. A rapid folk-dance, the skočná, follows. Vašek is entranced by Esmeralda, but his timid advances are interrupted when the "Indian" rushes in, announcing that the "bear" has collapsed in a drunken stupor. A replacement is required. Vašek is soon persuaded to take the job, egged on by Esmeralda's flattering words ("We'll make a pretty thing out of you").

The circus folk leave. Vasek's parents – Mícha and Háta – arrive, with Kecal. Vašek tells them that he no longer wants to marry Mařenka, having learned her true nature from a beautiful, strange girl. They are horrified ("He does not want her – what has happened?"). Vašek runs off, and moments later Mařenka arrives with her parents. She has just learned of Jeník's deal with Kecal, and a lively ensemble ("No, no, I don't believe it") ensues. Matters are further complicated when Vašek returns, recognises Mařenka as his "strange girl", and says that he will happily marry her. In the sextet which follows ("Make your mind up, Mařenka"), Mařenka is urged to think things over. They all depart, leaving her alone.

In her aria ("Oh what grief"), Mařenka sings of her betrayal. When Jeník appears, she rebuffs him angrily, and declares that she will marry Vašek. Kecal arrives, and is amused by Jeník's attempts to pacify Mařenka, who orders her former lover to go. The villagers then enter, with both sets of parents, wanting to know Mařenka's decision ("What have you decided, Mařenka?"). As she confirms that she will marry Vašek, Jeník returns, and to great consternation addresses Mícha as "father". In a surprise identity revelation it emerges that Jeník is Mícha's elder son, by a former marriage – the "worthless good-for-nothing" earlier dismissed by Kecal – who had in fact been driven away by his jealous stepmother, Háta. As Mícha's son he is, by the terms of the contract, entitled to marry Mařenka; when this becomes clear, Mařenka understands his actions and embraces him. Offstage shouting interrupts the proceedings; it seems that a bear has escaped from the circus and is heading for the village. This creature appears, but is soon revealed to be Vašek in the bear's costume ("Don't be afraid!"). His antics convince his parents that he is unready for marriage, and he is marched away. Mícha then blesses the marriage between Mařenka and Jeník, and all ends in a celebratory chorus.

Reception and performance history

Premiere

The premiere of The Bartered Bride took place at the Provisional Theatre on 30 May 1866. Smetana conducted; the stage designs were by Josef Macourek and Josef Jiři Kolár produced the opera.[16] The role of Mařenka was sung by the theatre's principal soprano, Eleonora von Ehrenberg – who had refused to appear in The Brandenburgers because she thought her proffered role was beneath her.[17] The parts of Krušina, Jeník and Kecal were all taken by leading members of the Brandenburgers cast.[18] A celebrated actor, Jindřich Mošna, was engaged to play the Ringmaster, a role which involves little singing skill.[16]

The choice of date proved unfortunate for several reasons. It clashed with a public holiday, and many people had left the city for the country. It was an intensely hot day, which further reduced the number of people prepared to suffer the discomfort of a stuffy theatre. Worse, the threat of an imminent war between Prussia and Austria caused unrest and anxiety in Prague, which dampened public enthusiasm for light romantic comedy. Thus on its opening night the opera, in its two-act version with spoken dialogue, was poorly attended and indifferently received.[19] Receipts failed to cover costs, and the theatre director was forced to pay Smetana's fee from his own pocket.[10]

Smetana's friend Josef Srb-Debrnov, who was unable to attend the performance himself, canvassed opinion from members of the audience as they emerged. "One praised it, another shook his head, and one well-known musician ... said to me: 'That's no comic opera; it won't do. The opening chorus is fine but I don't care for the rest.'"[10] Josef Krejčí, a member of the panel that had judged Harrach's opera competition, called the work a failure "that would never hold its own."[19] Press comment was less critical; nevertheless, after one more performance the opera was withdrawn. Shortly afterwards the Provisional Theatre temporarily closed its doors, as the threat of war drew closer to Prague.[19]

Restructure

Smetana began revising The Bartered Bride as soon as its first performances were complete.[10] For its first revival, in October 1866, the only significant musical alteration was the addition of a gypsy dance near the start of Act II. For this, Smetana used the music of a dance from The Brandenburgers of Bohemia.[20] When The Bartered Bride returned to the Provisional Theatre in January 1869, this dance was removed, and replaced with a polka. A new scene, with a drinking song for the chorus, was added to Act I, and Mařenka's Act II aria "Oh what grief!" was extended.[20]

So far, changes to the original had been of a minor nature; when the opera reappeared in June 1869, however, it had been entirely restructured. Although the musical numbers were still linked by dialogue, the first act had been divided in two, to create a three-act opera.[20] Various numbers, including the drinking song and the new polka, were repositioned, and the polka was now followed by a furiant. A "March of the Comedians" was added, to introduce the strolling players in what was now Act III. A short duet for Esmeralda and the Principal Comedian was dropped.[20][21] In September 1870 The Bartered Bride reached its final form, when all the dialogue was replaced by recitative.[20] Smetana's own opinion of the finished work, given much later, was largely dismissive: he described it as "a toy ... composing it was mere child's play". It was written, he said "to spite those who accused me of being Wagnerian and incapable of doing anything in a lighter vein."[22]

Later performances

In February 1869 Smetana had the text translated into French, and sent the libretto and score to the Paris Opera with a business proposal for dividing the profits. The management of the Paris Opera did not respond.[23] The opera was first performed outside its native land on 11 January 1871, when Eduard Nápravník, conductor of the Russian Imperial Opera, gave a performance at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. The work attracted mediocre notices from the critics, one of whom compared the work unfavourably to the Offenbach genre. Smetana was hurt by this remark, which he felt downgraded his opera to operetta status,[24] and was convinced that press hostility had been generated by a former adversary, the Russian composer Mily Balakirev. The pair had clashed some years earlier, over the Provisional Theatre's stagings of Glinka's A Life for the Tsar and Ruslan and Lyudmila. Smetana believed that Balakirev had used the Russian premiere of The Bartered Bride as a means of exacting revenge.[25]

The Bartered Bride was not performed abroad again until after Smetana's death in 1884. It was staged by the Prague National Theatre company in Vienna, as part of the Vienna Music and Theatre Exhibition of 1892, where its favourable reception was the beginning of its worldwide popularity among opera audiences.[16] Since the Czech language was not widely spoken, international performances tended to be in German. The United States premiere took place at the Haymarket Theatre, Chicago, on 20 August 1893.[26] The opera was introduced to Germany in 1894 by Gustav Mahler, then serving as Director of the Hamburg State Opera;[27] a year later a German company brought a production to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London.[28] In 1897, after his appointment as Director of the Vienna State Opera, Mahler brought The Bartered Bride into the company's repertory, and conducted regular performances of the work between 1899 and 1907.[27] Mahler's enthusiasm for the work was such that he had incorporated a quote from the overture into the final movement of his First Symphony (1888).[27] When he became Director of the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1907 he added the opera to its repertory.[27] The New York premiere, again in German, took place on 19 February 1909, and was warmly received. The New York Times commented on the excellence of the staging and musical characterisations, and paid particular tribute to "Mr. Mahler", whose master hand was in evidence throughout. Mahler chose to play the overture between Acts I and II, so that latecomers might hear it.[29]

Modern revivals

The opera was performed more than one hundred times during Smetana's lifetime (the first Czech opera to reach this landmark),[30] subsequently becoming a permanent feature of the National Theatre's repertory. On 9 May 1945 a special performance in memory of the victims of World War II was given at the theatre, four days after the last significant fighting in Europe.[31] In 2008 the young director Magdaléna Švecová became the first woman to direct The Bartered Bride at the National Theatre.[32]

In the years since its American premiere The Bartered Bride has entered the repertory of all major opera companies, and is regularly revived worldwide. After a number of unsuccessful attempts to stage it in France, it was belatedly premiered at the Opéra-Comique in Paris in 1928, sung in French as La Fiancée vendue.[33][34] It was not until 2008 that the opera was added to the repertoire of the Paris Opera, in a new production staged at the Palais Garnier.[35]

In the English-speaking world, recent productions of The Bartered Bride in London have included the Royal Opera House (ROH) presentation in 1998, staged at Sadler's Wells during the restoration of the ROH's headquarters at Covent Garden. This production in English was directed by Francesca Zambello and conducted by Bernard Haitink; it was criticised both for its stark settings and for ruining the Act II entrance of Vašek. It was nevertheless twice revived by the ROH – in 2001 and 2006, under Charles Mackerras.[36] [37]

A New York Metropolitan staging was in 1996 under James Levine, a revival of John Dexter's 1978 production with stage designs by Josef Svoboda. In 2005 The Bartered Bride returned to New York, at the Juilliard School theatre, in a new production by Eve Shapiro, conducted by Mark Stringer.[38] In its May 2009 production at the Cutler Majestic Theatre, Opera Boston transplanted the action to 1934, in the small Iowan town of Spillville, once the home of a large Czech settlement.[39]

Music

Although much of the music of The Bartered Bride is folk-like, the only significant use of authentic folk material is in the Act II furiant,[40] with a few other occasional glimpses of basic Czech folk melodies.[41] The "Czechness" of the music is further illustrated by the closeness to Czech dance rhythms of many individual numbers.[16] Smetana's diary indicates that he was trying to give the music "a popular character, because the plot [...] is taken from village life and demands a national treatment."[14] According to his biographer John Clapham, Smetana "certainly felt the pulse of the peasantry and knew how to express this in music, yet inevitably he added something of himself."[41] Historian Harold Schonberg argues that "the exoticisms of the Bohemian musical language were not in the Western musical consciousness until Smetana appeared." Smetana's musical language is, on the whole, one of happiness, expressing joy, dancing and festivals.[42]

The mood of the entire opera is set by the overture, a concert piece in its own right, which Tyrrell describes as "a tour de force of the genre, wonderfully spirited & wonderfully crafted." Tyrrell draws attention to several of its striking features – its extended string fugato, climactic tutti and prominent syncopations.[16] The overture does not contain many of the opera's later themes: biographer Brian Large compares it to Mozart's overtures to The Marriage of Figaro and The Magic Flute, in establishing a general mood.[43] It is followed immediately by an extended orchestral prelude, for which Smetana adapted part of his 1849 piano work Wedding Scenes, adding special effects such as bagpipe imitations.[16][44]

Schonberg has suggested that Bohemian composers express melancholy in a delicate, elegiac manner "without the crushing world-weariness and pessimism of the Russians."[42] Thus, Mařenka's unhappiness is illustrated in the opening chorus by a brief switch to the minor key; likewise, the inherent pathos of Vašek's character is demonstrated by the dark minor key music of his Act III solo.[16] Smetana also uses the technique of musical reminiscence, where particular themes are used as reminders of other parts of the action; the lilting clarinet theme of "faithful love" is an example, though it and other instances fall short of being full-blown Wagnerian leading themes or Leitmotifs.[45]

Large has commented that despite the colour and vigour of the music, there is little by way of characterisation, except in the cases of Kecal and, to a lesser extent, the loving pair and the unfortunate Vašek. The two sets of parents and the various circus folk are all conventional and "penny-plain" figures.[45] In contrast, Kecal's character – that of a self-important, pig-headed, loquacious bungler – is instantly established by his rapid-patter music.[16][45] Large suggests that the character may have been modelled on that of the boastful Baron in Cimarosa's opera Il matrimonio segreto.[45] Mařenka's temperament is shown in vocal flourishes which include coloratura passages and sustained high notes, while Jeník's good nature is reflected in the warmth of his music, generally in the G minor key. For Vašek's dual image, comic and pathetic, Smetana uses the major key to depict comedy, the minor for sorrow. Large suggests that Vašek's musical stammer, portrayed especially in his opening Act II song, was taken from Mozart's character Don Curzio in The Marriage of Figaro.[46]

Film and other adaptations

A silent film of The Bartered Bride was made in 1913 by the Czech film production studio Kinofa. It was produced by Max Urban and starred his wife Andula Sedláčková.[47] A German-language version of the opera, Die verkaufte Braut, was filmed in 1932 by Max Ophüls (1902–57), the celebrated German director then at the beginning of his film-making career.[48] The screenplay was drawn from Sabina's libretto by Curt Alexander, and Smetana's music was adapted by the German composer of film music, Theo Mackeben. The film starred the leading Czech opera singer Jarmila Novotná in the role of Mařenka ("Marie" in the film), and the German baritone Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender as Jeník ("Hans"). The veteran comedy film actor Max Schreck also appeared in the film, in the small role of "Muff", the circus comedian.[49]

Ophuls constructed an entire Czech village in the studio to provide an authentic background.[48] Following the film's US release in 1934, The New York Times commented that it "carr[ied] most of the comedy of the original" but was "rather weak on the musical side", despite the presence of stars such as Novotná. Opera-lovers, the review suggested, should not expect too much, but the work nevertheless gave an attractive portrait of Bohemian village life in the mid-19th century. The reviewer found most of the acting first-rate, but commented that "the photography and sound reproduction are none too clear at times."[50] Other film adaptations of the opera were made in 1922 directed by Oldrich Kminek (Atropos), in 1933, directed by Jaroslav Kvapil, Svatopluk Innemann and Emil Pollert (Espofilm), and in 1976, directed by Václav Kašlík (Barrandov).[51]

List of musical numbers

The list relates to the final (1870) version of the opera.

| Number | Performed by | Title (Czech) | Title (English)[52] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overture | Orchestra | ||

| Act I Opening Chorus |

Villagers | Proč bychom se netěšili | "Let's rejoice and be merry" |

| Aria | Mařenka | Kdybych se co takového | "If I should ever learn" |

| Duet | Mařenka and Jeník | Jako matka požehnáním ... Věrné milování | "While a mother's love..." (leading to) "Faithful love can't be marred" |

| Trio | Ludmila, Krušina, Kecal | Jak vám pravím, pane kmotře | "As I was saying, my good fellow" |

| Trio | Ludmila, Krušina, Kecal | Mladík slušný | "He's a nice boy, well brought up" |

| Quartet | Ludmila, Krušina, Kecal, Mařenka | Tu ji máme | "Here she is now" |

| Dance: Polka | Chorus and orchestra | Pojd' sem, holka, toč se, holka | "Come, my darlings!" |

| Act II Chorus with soloists |

Chorus, Kecal, Jeník | To pivečko | "To beer!" |

| Dance: Furiant | Orchestra | ||

| Aria | Vašek | Má ma-ma Matička | "My-my-my mother said to me" |

| Duet | Mařenka and Vašek | Známť já jednu dívčinu | "I know of a maiden fair" |

| Duet | Kecal and Jeník | Nuže, milý chasníku, znám jednu dívku | "Now, sir, listen to a word or two" |

| Aria | Jeník | Až uzříš – Jak možna věřit | "When you discover whom you've bought" |

| Ensemble | Kecal, Jeník, Krušina, Chorus | Pojďte lidičky | "Come inside and listen to me" |

| Act III Aria |

Vašek | To-to mi v hlavě le-leži | "I can't get it out of my head" |

| March of the Comedians | Orchestra | ||

| Dance: Skočná | Orchestra | ||

| Duet | Esmeralda, Principál | Milostné zvířátko | "We'll make a pretty thing out of you" |

| Quartet | Háta, Mícha, Kecal, Vašek | Aj! Jakže? Jakže? | "He does not want her – what has happened" |

| Ensemble | Mařenka, Krušina, Kecal, Ludmila, Háta, Mícha, Vašek | Ne, ne, tomu nevěřím | "No, no, I don't believe it" |

| Sextet | Ludmila, Krušina, Kecal, Mařenka, Háta, Mícha, | Rozmmysli si, Mařenko | "Make your mind up, Mařenka" |

| Aria | Mařenka | Ó, jaký žal ... Ten lásky sen | "Oh what grief"... (leading to) "That dream of love" |

| Duet | Jeník and Mařenka | Mařenko má! | "Mařenka mine!" |

| Trio | Jeník, Mařenka, Kecal | Utiš se, dívko | "Calm down and trust me" |

| Ensemble | Chorus, Mařenka, Jeník, Háta, Mícha, Kecal, Ludmila, Krušina, | Jak jsi se, Mařenko rozmyslila? | "What have you decided, Mařenka?" |

| Finale | All characters and Chorus | Pomněte, kmotře ... Dobrá věc se podařila | "He's not grown up yet..." (leading to) "A good cause is won, and faithful love has triumphed." |

Recordings

See The Bartered Bride discography.

References

- Notes

- ^ Die verkaufte Braut (1932) at IMDb

- ^ Large, pp. 67–69

- ^ Clapham, p. 138

- ^ Clapham, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f Abraham, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b Clapham. p. 31

- ^ Large, p. 43

- ^ Large, p. 99

- ^ a b c d Large, pp. 160–61

- ^ a b c d Abraham, p. 31

- ^ Tyrrell, John. "The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta)". In Macy, Laura (ed.) (ed.). Grove Music Online,. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) (subscription required) - ^ Large, pp. 121–25

- ^ Clapham.p. 32

- ^ a b c Large, pp. 163–64

- ^ "Prodaná nevěsta". Toulky operou. Retrieved 28 March 2012. (in Czech)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tyrrell, John. "The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta)". In Macy, Laura (ed.) (ed.). Grove Music Online. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help) (subscription required) - ^ Large, p. 144

- ^ Large, p. 164

- ^ a b c Large, pp. 165–66

- ^ a b c d e Large, pp. 399–408

- ^ This duet is reproduced in Large, pp. 409–13

- ^ Large, p. 160

- ^ Large, pp. 168–69

- ^ Large, p. 171

- ^ Large, p. 210

- ^ The Viking Opera Guide. London: Viking. 1993. p. 989. ISBN 0-670-81292-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Hefling, pp. 111–12

- ^ Newmarch, pp. 67–68

- ^ "Bartered Bride at Metropolitan". The New York Times. 20 February 1909. Retrieved 20 June 2009. PDF format

- ^ Large, pp. 356–57

- ^ Sayer, p. 235

- ^ "The Bartered Bride". Národní divadlo. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Nichols, p. 17

- ^ Marès, p. 48

- ^ Lesueur, François (22 October 2008). "Enfin par la grande porte: La Fiancée vendue". ForumOpera.com. Retrieved 30 November 2015. (in French)

- ^ Seckerson, Edward (11 January 2006). "Shut your eyes and all is perfect". The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ White, Michael (13 December 1998). "The bride wore an outfit from Habitat". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Robinson, Lisa B. (November 2011). "Met-Juilliard Bride Bows". The Juilliard Journal online. New York: The Juilliard School. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Eichler, Jeremy (2 May 2009). "Smetana's buoyant Bride". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ Large, pp. 186–87

- ^ a b Clapham, p. 95

- ^ a b Schonberg, p. 78

- ^ Large, p. 173

- ^ Clapham, p. 59

- ^ a b c d Large, pp. 174–75

- ^ Large, pp. 176–78

- ^ Osnes, Beth (2001). Acting: An International Encyclopedia. Oxford: ABC-Clio. p. 82. ISBN 0-87436-795-6. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Moving Pictures: The European Films of Max Ophuls". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ "Die verkaufte Braut". British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ H.T.S. (27 April 1934). "Verkaufte Braut (1932)". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Turconi, Davide. Filmographie: Cinéma et opéra: du film muet à la vidéo. In: L'Avant Scène Cinéma et Opéra, Mai 1987, 360, pp. 138–39.

- ^ The English wordings are taken from Brian Large's Smetana, Appendix C: "The Genesis of The Bartered Bride", pp. 399–408

- Sources

- Abraham, Gerald (1968). Slavonic and Romantic Music. London: Faber and Faber.

- "Bartered Bride at Metropolitan". The New York Times. 20 February 1909. Retrieved 20 June 2009. PDF format

- Brandow, Adam (April 2005). "Czech Spirit Enlivens J.O.C.'s Bartered Bride". The Juilliard Journal online. XX (7). New York: The Juilliard School. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Clapham, John (1972). Smetana (Master Musicians series). London: J.M. Dent. ISBN 0-460-03133-3.

- "Die verkaufte Braut". British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- Eichler, Jeremy (2 May 2009). "Smetana's buoyant Bride". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- Hefling, Stephen (ed.) (1997). Mahler Studies (Essay: Mahler and Smetana by Donald Mitchell). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47165-6. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Kalbeck, Max & Raboch, Wenzel (1909). The Bartered Bride libretto: German and English texts. New York: Oliver Ditson Company.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Large, Brian (1970). Smetana. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-0512-7.

- Marès, Antoine (2006). "La Fiancée mal vendue" in Horel, Catherine and Michel, Bernard (eds): Nations, cultures et sociétés d'Europe centrale aux XIXe et XXe siècles. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 2-85944-550-1. (in French)

- "Moving Pictures: The European Films of Max Ophuls". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- Newmarch, Rosa (1942). The Music of Czechoslovakia. Oxford: OUP. OCLC 3291947.

- Nichols, Roger (2002). The Harlequin Years: Music in Paris, 1917-1929. Berkeley, Ca.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23736-6.

- Osnes, Beth (2001). Acting. Oxford: ABC-Clio. ISBN 0-87436-795-6. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- Seckerson, Edward (11 January 2006). "Shut your eyes and all is perfect". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- "The Bartered Bride 20 June 2008". Národní divlado (National Theatre, Prague). June 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Tyrrell, John. "The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta)". In Macy, Laura (ed.) (ed.). Grove Music Online. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help) (subscription required) - H.T.S. (27 April 1934). "Verkaufte Braut (1932)". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- White, Michael (13 December 1998). "The bride wore an outfit from Habitat". The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

External links

- Die verkaufte Braut Public domain copy of Max Ophüls 1932 film at Internet Archive.

- Supraphon Details of a 2009 CD reissue of 1952 recording; includes link to a full libretto in English