The Decameron

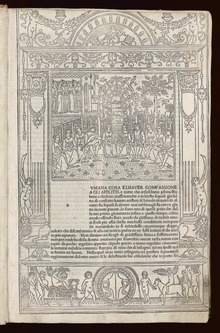

Illustration from a ca. 1492 edition of Il Decameron published in Venice | |

| Author | Giovanni Boccaccio |

|---|---|

| Original title | Decamerone |

| Translator |

|

| Language | Italian (Florentine) |

| Genre | Frame story, novellas |

| Publisher | Filippo and Bernardo Giunti |

| Publication place | Italy |

Published in English | 1886 |

| OCLC | 58887280 |

| 853.1 | |

| LC Class | PQ4267 |

The Decameron (Italian: Decameron [deˈkaːmeron; dekameˈrɔn; dekameˈron] or Decamerone [dekameˈroːne]), subtitled Prince Galehaut (Old Italian: Prencipe Galeotto [ˈprentʃipe ɡaleˈɔtto; ˈprɛntʃipe]), is a collection of novellas by the 14th-century Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375). The book is structured as a frame story containing 100 tales told by a group of seven young women and three young men sheltering in a secluded villa just outside Florence to escape the Black Death, which was afflicting the city. Boccaccio probably conceived the Decameron after the epidemic of 1348, and completed it by 1353. The various tales of love in The Decameron range from the erotic to the tragic. Tales of wit, practical jokes, and life lessons contribute to the mosaic. In addition to its literary value and widespread influence (for example on Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales), it provides a document of life at the time. Written in the vernacular of the Florentine language, it is considered a masterpiece of classical early Italian prose.[1]

Title

The book's primary title exemplifies Boccaccio's fondness for Greek philology: Decameron combines two Greek words, δέκα, déka ("ten") and ἡμέρα, hēméra ("day"), to form a term that means "ten-day [event]".[2] Ten days is the period in which the characters of the frame story tell their tales.

Boccaccio's subtitle, Prencipe Galeotto (Prince Galehaut), refers to Galehaut, a fictional king portrayed in the Lancelot-Grail who was sometimes called by the title haut prince ("high prince"). Galehaut was a close friend of Lancelot and an enemy of King Arthur. When Galehaut learned that Lancelot loved Arthur's wife, Guinevere, he set aside his own ardor for Arthur (mistakenly put down as Lancelot) in order to arrange a meeting between his friend and Guinevere. At this meeting the Queen first kisses Lancelot, and so begins their love affair.

In Canto V of Inferno, Dante compares these fictional lovers with the real-life paramours Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, whose relationship he fictionalises. In Infierno, Francesca and Paolo read of Lancelot and Guinevere, and the story impassions them to lovemaking.

Dante's description of Galehaut's munificence and savoir-faire amidst this intrigue impressed Boccaccio. By invoking the name Prencipe Galeotto in the alternative title to Decameron, Boccaccio alludes to a sentiment he expresses in the text: his compassion for women deprived of free speech and social liberty, confined to their homes and, at times, lovesick. He contrasts this life with that of the menfolk, who enjoy respite in sport, such as hunting, fishing, riding, and falconry.[3]

Frame story

In Italy during the time of the Black Death, a group of seven young women and three young men flee from plague-ridden Florence to a deserted villa in the countryside of Fiesole for two weeks. To pass the evenings, every member of the party tells a story each night, except for one day per week for chores, and the holy days in which they do no work at all, resulting in ten nights of storytelling over the course of two weeks. Thus, by the end of the fortnight they have told 100 stories.

Each of the ten characters is charged as King or Queen of the company for one of the ten days in turn. This charge extends to choosing the theme of the stories for that day, and all but two days have topics assigned: examples of the power of fortune; examples of the power of human will; love tales that end tragically; love tales that end happily; clever replies that save the speaker; tricks that women play on men; tricks that people play on each other in general; examples of virtue. Only Dioneo, who usually tells the tenth tale each day, has the right to tell a tale on any topic he wishes, due to his wit.[5][6] Many authors have argued that Dioneo expresses the views of Boccaccio himself.[7] Each day also includes a short introduction and conclusion to continue the frame of the tales by describing other daily activities besides story-telling. These frame tale interludes frequently include transcriptions of Italian folk songs.[8] The interactions among tales in a day, or across days, as Boccaccio spins variations and reversals of previous material, forms a whole and not just a collection of stories. The basic plots of the stories including mocking the lust and greed of the clergy; tensions in Italian society between the new wealthy commercial class and noble families; the perils and adventures of traveling merchants.

Analysis

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2012) |

Throughout Decameron the mercantile ethic prevails and predominates. The commercial and urban values of quick wit, sophistication, and intelligence are treasured, while the vices of stupidity and dullness are cured, or punished. While these traits and values may seem obvious to the modern reader, they were an emerging feature in Europe with the rise of urban centers and a monetized economic system beyond the traditional rural feudal and monastery systems which placed greater value on piety and loyalty. [citation needed]

Beyond the unity provided by the frame narrative, Decameron provides a unity in philosophical outlook. Throughout runs the common medieval theme of Lady Fortune, and how quickly one can rise and fall through the external influences of the "Wheel of Fortune". Boccaccio had been educated in the tradition of Dante's Divine Comedy, which used various levels of allegory to show the connections between the literal events of the story and the Christian message. However, Decameron uses Dante's model not to educate the reader but to satirize this method of learning. The Roman Catholic Church, priests, and religious belief become the satirical source of comedy throughout. This was part of a wider historical trend in the aftermath of the Black Death which saw widespread discontent with the church.

Many details of the Decameron are infused with a medieval sense of numerological and mystical significance.[citation needed] For example, it is widely believed[by whom?] that the seven young women are meant to represent the Four Cardinal Virtues (Prudence, Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude) and the Three Theological Virtues (Faith, Hope, and Charity). It is further supposed[by whom?] that the three men represent the classical Greek tripartite division of the soul (Reason, Spirit, and Appetite, see Book IV of Republic). Boccaccio himself notes that the names he gives for these ten characters are in fact pseudonyms chosen as "appropriate to the qualities of each". The Italian names of the seven women, in the same (most likely significant) order as given in the text, are: Pampinea, Fiammetta, Filomena, Emilia, Lauretta, Neifile, and Elissa. The men, in order, are: Panfilo, Filostrato, and Dioneo.

Boccaccio focused on the naturalness of sex by combining and interlacing sexual experiences with nature.

Literary sources

Boccaccio borrowed the plots of almost all his stories (just as later writers borrowed from him). Although he consulted only French, Italian and Latin sources, some of the tales have their origin in such far-off lands as India, Persia, Spain, and other places. Some were already centuries old. For example, part of the tale of Andreuccio of Perugia (II, 5) originated in 2nd century Ephesus (in the Ephesian Tale). The frame narrative structure (though not the characters or plot) originates from the Panchatantra, which was written in Sanskrit before AD 500 and came to Boccaccio through a chain of translations that includes Old Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin. Even the description of the central current event of the narrative, the Black Plague (which Boccaccio surely witnessed), is not original, but based on the Historia gentis Langobardorum of Paul the Deacon, who lived in the 8th century.

Some scholars have suggested that some of the tales for which there is no prior source may still not have been invented by Boccaccio, but may have been circulating in the local oral tradition, with Boccaccio simply the first person known to have recorded them. Boccaccio himself says that he heard some of the tales orally. In VII, 1, for example, he claims to have heard the tale from an old woman who heard it as a child.

The fact that Boccaccio borrowed the storylines that make up most of the Decameron does not mean he mechanically reproduced them. Most of the stories take place in the 14th century and have been sufficiently updated to the author's time that a reader may not know that they had been written centuries earlier or in a foreign culture. Also, Boccaccio often combined two or more unrelated tales into one (such as in II, 2 and VII, 7).

Moreover, many of the characters actually existed, such as Giotto di Bondone, Guido Cavalcanti, Saladin and King William II of Sicily. Scholars have even been able to verify the existence of less famous characters, such as the tricksters Bruno and Buffalmacco and their victim Calandrino. Still other fictional characters are based on real people, such as the Madonna Fiordaliso from tale II, 5, who is derived from a Madonna Flora who lived in the red light district of Naples. Boccaccio often intentionally muddled historical (II, 3) and geographical (V, 2) facts for his narrative purposes. Within the tales of the Decameron, the principal characters are usually developed through their dialogue and actions, so that by the end of the story they seem real and their actions logical given their context.

Another of Boccaccio's frequent techniques was to make already existing tales more complex. A clear example of this is in tale IX, 6, which was also used by Chaucer in his "The Reeve's Tale", which more closely follows the original French source than does Boccaccio's version. In the Italian version, the host's wife (in addition to the two young male visitors) occupy all three beds and she also creates an explanation of the happenings of the evening. Both elements are Boccaccio's invention and make for a more complex version than either Chaucer's version or the French source (a fabliau by Jean de Boves).

Translations into English

The Decameron's individual tales were translated into English early on (such as William Walter's 1525 Here begynneth y[e] hystory of Tytus & Gesyppus translated out of Latyn into Englysshe by Wyllyam Walter, somtyme seruaunte to Syr Henry Marney, a translation of tale X.viii), or served as source material for English authors such as Chaucer to rework. The table below lists all attempts at a complete English translation of the book. The information on pre-1971 translations is compiled from the G.H. McWilliam's introduction to his own 1971 translation.

| Year | Translator | Completeness/Omissions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1620 | Anonymous, attributed to John Florio | Omits the Proemio and Conclusione dell’autore. Replaces tale III.x with an innocuous tale taken from François de Belleforest’s “Histoires tragiques”, concluding that it “was commended by all the company, ... because it was free from all folly and obscoeneness.” Tale IX.x is also modified, while tale V.x loses its homosexual innuendo. | “Magnificent specimen of Jacobean prose, [but] its high-handed treatment of the original text produces a number of shortcomings” says G.H. McWilliam, translator of the 1971 Penguin edition (see below). Based not on Boccaccio’s Italian original, but on Antoine Le Maçon’s 1545 French translation and Leonardo Salviati's 1582 Italian edition which replaced ‘offensive’ words, sentences or sections with asterisks or altered text (in a different font). |

| 1702 | Anonymous, attributed to John Savage | Omits Proemio and Conclusione dell’autore. Replaces tale III.x with the tale contained within the Introduction to the Fourth Day. Tale IX.x is bowdlerised, but possibly because the translator was working from faulty sources, rather than deliberately. | --- |

| 1741 | Anonymous, posthumously identified as Charles Balguy | Omits Proemio and Conclusione dell’autore. Explicitly omits tales III.x and IX.x, and removed the homosexual innuendo in tale V.x: “Boccace is so licentious in many places, that it requires some management to preserve his wit and humour, and render him tolerably decent. This I have attempted with the loss of two novels, which I judged incapable of such treatment; and am apprehensive, it may still be thought by some people, that I have rather omitted to little, than too much.” | Reissued several times with small or large modifications, sometimes without acknowledgement of the original translator. The 1804 reissue makes further expurgations. The 1822 reissue adds half-hearted renditions of III.x and IX.x, retaining the more objectionable passages in the original Italian, with a footnote to III.x that it is “impossible to render... into tolerable English”, and giving Mirabeau’s French translation instead. The 1872 reissue is similar, but makes translation errors in parts of IX.x. The 1895 reissue (introduced by Alfred Wallis), in 4 volumes, cites Mr. S. W. Orson as making up for the omissions of the 1741 original, although part of III.x is given in Antoine Le Maçon’s French translation, belying the claim that it is a complete English translation, and IX.x is modified, replacing Boccaccio’s direct statements with innuendo. |

| 1855 | W. K. Kelly | Omits Proemio and Conclusione dell’autore. Includes tales III.x and IX.x, claiming to be “COMPLETE, although a few passages are in French or Italian”, but as in 1822, leaves parts of III.x in the original Italian with a French translation in a footnote, and omits several key sentences entirely from IX.x. | --- |

| 1886 | John Payne | First truly complete translation in English, with copious footnotes to explain Boccaccio’s double-entendres and other references. Introduction by Sir Walter Raleigh. | Published by the Villon Society by private subscription for private circulation. Stands and falls on its “splendidly scrupulous but curiously archaic... sonorous and self-conscious Pre-Raphaelite vocabulary” according to McWilliam, who gives as an example from tale III.x: “Certes, father mine, this same devil must be an ill thing and an enemy in very deed of God, for that it irketh hell itself, let be otherwhat, when he is put back therein.” 1925 Edition by Horace Liveright Inc. USA, then reprinted in Oct 1928, Dec 1928, April 1929,Sept 1929, Feb 1930. 1930. Reissued in the Modern Library, 1931. Updated editions have been published in 1982, edited by Charles S. Singleton, and in 2004, edited by Cormac Ó Cuilleanáin. |

| 1896 | Anonymous | Part of tale III.x again given in French, without footnote or explanation. Tale IX.x translated anew, but Boccaccio’s phrase “l’umido radicale” is rendered “the humid radical” rather than “the moist root”. | Falsely claims to be a “New Translation from the Italian” and the “First complete English Edition”, when it is only a reworking of earlier versions with the addition of what McWilliam calls “vulgarly erotic overtones” in some stories. |

| 1903 | J. M. Rigg | Once more, part of tale III.x is left in the original Italian with a footnote “No apology is needed for leaving, in accordance with precedent, the subsequent detail untranslated”. | McWiliam praises its elegant style in sections of formal language, but that it is spoiled by an obsolete vocabulary in more vernacular sections. Reissued frequently, including in Everyman's Library (1930) with introduction by Edward Hutton. |

| 1930a | Frances Winwar | Omits the Proemio. | Introduction by Burton Rascoe. First American translation, and first English-language translation by a female. “Fairly accurate and eminently readable, [but] fails to do justice to those more ornate and rhetorical passages” says McWilliam. Originally issued in expensive 2-volume set by the Limited Editions Club of New York City, and in cheaper general circulation edition only in 1938. |

| 1930b | Richard Aldington | Complete. | Like Winwar, first issued in expensive and lavishly illustrated edition. “Littered with schoolboy errors... plain and threadbare, so that anyone reading it might be forgiven for thinking that Boccaccio was a kind of sub-standard fourteenth-century Somerset Maugham” say McWilliam. |

| 1972 | George Henry McWilliam | First complete translation into contemporary English, intended for general circulation. | Penguin Classics edition. The second edition (1995) includes a 150-page detailed explanation of the historical, linguistic, and nuanced reasoning behind the new translation. Its in-depth study exemplifies the care and consideration given to the original text and meaning. There is a near biographical history of both the author and the book itself, as well as a detailed description of the history on both the street (poor/merchants) and in the upper echelons (aristocracy/church). Boccaccio lived with a foot on both sides of the fence: as a lawyer for the merchants, a writer for the church, and as one who lived among the public and felt their misfortune and celebrated their joys. He secretly believed in equal rights (more than 600 years ago) -- which was a capital offence back then and carried the death penalty, yet he outwitted those people and so... -- this book is his legacy. |

| 1977 | Peter Bondanella and Mark Musa | Complete | W. W. Norton & Company |

| 2013 | Wayne A. Rebhorn | Complete | W. W. Norton & Company. Publishers Weekly called Rebhorn's translation "strikingly modern" and praised its "accessibility".[9] In an interview with The Wall Street Journal Rebhorn stated that he started translating the work in 2006 after deciding that the translations he was using in his classroom needed improvement. Rebhorn cited errors in the 1977 translation as one of the reasons for the new translation. Peter Bondanella, one of the translators of the 1977 edition, stated that new translations build on previous ones and that the error cited would be corrected in future editions of his translation.[10] |

Literary influence

The stories from the Decameron influenced many later writers. Notable examples include:

- Edgar Allan Poe's short horror story The Masque of the Red Death is said to be inspired by this work.[citation needed]

- The famous first tale (I, 1) of the notorious Ser Ciappelletto was later translated into Latin by Olimpia Fulvia Morata and translated again by Voltaire.

- Martin Luther retells tale I, 2, in which a Jew converts to Catholicism after visiting Rome and seeing the corruption of the Catholic hierarchy. However, in Luther's version (found in his "Table-talk #1899"), Luther and Philipp Melanchthon try to dissuade the Jew from visiting Rome.

- Marguerite de Navarre's Heptaméron is heavily based on the Decameron

- The ring parable is at the heart of both Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's 1779 play Nathan the Wise and tale I, 3. In a letter to his brother on August 11, 1778, he says explicitly that he got the story from the Decameron. Jonathan Swift also used the same story for his first major published work, A Tale of a Tub.

- Posthumus's wager on Imogen's chastity in Cymbeline was taken by Shakespeare from an English translation of a 15th-century German tale, "Frederyke of Jennen", whose basic plot came from tale II, 9.

- Both Molière and Lope de Vega use tale III, 3 to create plays in their respective vernaculars. Molière wrote L'école des maris in 1661 and Lope de Vega wrote Discreta enamorada.

- Tale III, 9, which Shakespeare converted into All's Well That Ends Well. Shakespeare probably first read a French translation of the tale in William Painter's Palace of Pleasure.

- Tale IV, 1 was reabsorbed into folklore to appear as Child ballad 269, Lady Diamond.[11]

- John Keats borrowed the tale of Lisabetta and her pot of basil (IV, 5) for his poem, Isabella, or the Pot of Basil.

- Lope de Vega also used parts of V, 4 for his play El ruiseñor de Sevilla (They're Not All Nightingales).

- Christoph Martin Wieland's set of six novellas Das Hexameron von Rosenhain is based on the structure of the Decameron.

- The title character in George Eliot's historical novel Romola emulates Gostanza in tale V, 2, by buying a small boat and drifting out to sea to die, after she realizes that she no longer has anyone on whom she can depend.

- Tale V, 9 became the source for works by two famous 19th century writers in the English language. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow used it in his "The Falcon of Ser Federigo" as part of Tales of a Wayside Inn in 1863. Alfred, Lord Tennyson used it in 1879 for a play entitled The Falcon.

- Molière also borrowed from tale VII, 4 in his George Dandin ou le Mari confondu (The Confounded Husband). In both stories the husband is convinced that he has accidentally caused his wife's suicide.

- Giuseppe Petrosinelli in his libretto for Domenico Cimarosa's opera The Italian Girl in London uses the story of the heliotrope (bloodstone) in tale VIII, 3.

- The motif of the three trunks in The Merchant of Venice by Shakespeare is found in tale X, 1. However, both Shakespeare and Boccaccio probably came upon the tale in Gesta Romanorum.

- At his death Percy Bysshe Shelley had left a fragment of a poem entitled "Ginevra", which he took from the first volume of an Italian book called L'Osservatore Fiorentino. The earlier Italian text had a plot taken from tale X, 4.

- Tale X, 5 shares its plot with Chaucer's "The Franklin's Tale", although this is not due to a direct borrowing from Boccaccio. Rather, both authors used a common French source.

- The tale of patient Griselda (X, 10) was the source of Chaucer's "The Clerk's Tale". However, there are some scholars who believe that Chaucer may not have been directly familiar with the Decameron, and instead derived it from a Latin translation/retelling of that tale by Petrarch. It can be generally said that Petrarch's version in Rerum senilium libri XVII, 3, included in a letter he wrote to his friend Boccaccio, was to serve as a source for all the many versions that circulated around Europe, including the translations of the very Decameron into French, Catalan - translated by Bernat Metge - and Spanish. Lope de Vega, who adapted at least twelve stories from the Decameron to the scenes, wrote El ejemplo de casadas y prueba de la paciencia on this tale, which was by far the most popular story of the Decameron during the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. The Venetian writer Apostolo Zeno made on it, and partially on Lope's play, a libretto named Griselda (1701) which was to be musicated, among others, by Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (1701), Antonio Maria Bononcini (1718), Alessandro Scarlatti (1721), Tomaso Albinoni (1728) and Antonio Vivaldi (1735).

- Christine de Pizan often used restructured tales from Decameron in her work "The Book of the City of Ladies" (1405).

- Thomas Middleton's play 'The Widow' is based on tales 2.2 and 3.3.

A number of film adaptations have been based on tales from The Decameron. Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Decameron (1971) is one of the most famous. Decameron Nights (1953) was based on three of the tales and starred Louis Jourdan as Boccaccio. Dino De Laurentiis produced a romantic comedy film version, Virgin Territory, in 2007. The tales are referenced in The Borgias (2011 TV series) in season 2, episode 7, when a fictional version of Niccolò Machiavelli mentions at a depiction of the Bonfire of the Vanities that he should have brought his friend "the Decameron" who would have told the "one-hundred and first" tale. The work is also mentioned and adapted in season 1, episode 5 of the American TV series Da Vinci's Demons.

Boccaccio's drawings

Since The Decameron was very popular among contemporaries, especially merchants, many manuscripts of it survive. The Italian philologist Vittore Branca did a comprehensive survey of them and identified a few copied under Boccaccio's supervision; some have notes written in Boccaccio's hand. Two in particular have elaborate drawings, probably done by Boccaccio himself. Since these manuscripts were widely circulated, Branca thought that they influenced all subsequent illustrations. In 1962 Branca identified Codex Hamilton 90, in Berlin's Staatsbibliothek, as an autograph belonging to Boccaccio's latter years.[12]

See also

References

- ^ "Giovanni Boccaccio: The Decameron.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ The title transliterates to Greek as δεκάμερον (τό) or, classically, δεχήμερον.

- ^ Boccaccio, "Proem"

- ^ "MS. Holkham misc. 49: Boccaccio, Decameron, Ferrara, c. 1467; illuminated by Taddeo Crivelli for Teofilo Calcagnini". Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. 2000–2003. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Lee Patterson Literary practice and social change in Britain, 1380–1530 p.186

- ^ Boccaccio, "Day the First"

- ^ The origin of the Griselda story p.7

- ^ Context, Third Paragraph

- ^ "The Decameron". Publishers Weekly. Sep 1, 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ Trachtenberg, Jeffrey (Sep 8, 2013). "How Many Times Can a Tale Be Told?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ Helen Child Sargent, ed; George Lyman Kittredge, ed English and Scottish Popular Ballads: Cambridge Edition p 583 Houghton Mifflin Company Boston 1904

- ^ Armando Petrucci, Il ms. Berlinese Hamilton 90. Note codicologiche e paleografiche, in G. Boccaccio, Decameron, Edizione diplomatico-interpretativa dell'autografo Hamilton 90 a cura di Charles S. Singleton, Baltimora, 1974.

External links

- Decameron Web, from Brown University

- The Decameron – Introduction from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- 'The Enchanted Garden', a painting by John William Waterhouse

- The Decameron, Volume I at Project Gutenberg (Rigg translation)

- The Decameron, Volume II at Project Gutenberg (Rigg translation)

- The Decameron at Project Gutenberg (Payne translation)

- Decameron – English and Italian text for a direct comparison

- Template:It icon Full text of the Decameron (PDF)

The Decameron public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Decameron public domain audiobook at LibriVox