The Diamond Troupe

The Diamond Troupe, 1917. Front row (from left to right): Pte. Eric John Dean, Lt. Col. E. Trevor Wright, Pte. Lawrence Nicol. Middle row: Pte. Hubert Holmes (cellist), Corp. Frank Pollard, L/Corp. Robert James Stannard, Pte. William Threlfall, Pte. Arthur Sykes, Pte. H. Palmer (violinist). Back row: Pte. Neville Giordano, Pte. Jock McKinley, Pte. Alec Hill, Pte. George Hangle, Pte. J. Morris. | |

| Type | Theatre group |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Concert party |

| Location | |

| Membership | Musicians, singers, and actors from nine regiments within the 29th Division (United Kingdom) |

The Diamond Troupe was the concert party of the 29th Division (United Kingdom), a First World War infantry division within the British Army. Also known as the "Incomparable Division", the 29th was formed in 1915 by combining units that had previously been acting as garrisons about the British Empire. The division fought throughout the Gallipoli Campaign and, from 1916 to the end of the war, on the Western Front in France.

Concert parties were an integral element of the war effort; and by 1917, virtually every division had at least one. They mirrored the Pierrot troupes of music halls and seaside resorts, offering soldiers a respite from war, reminding them of home, and providing a neutral outlet to air grievances about "food, conditions, and sergeants".[1]

The Diamond Troupe was one of a small number of concert parties to achieve considerable notoriety, both on the battlefield and at home. Its success was due to a combination of factors, not the least of which were the fame of the Division itself and the exceptional performances of many troupe members, especially by what historian Larry J Collins described as "the show-stopper": the female impersonator.[2] The troupe's music director, Robert James Stannard, wrote in his diary that "…the biggest hits were [Alec] Hill with his fine singing, Queenie [the troupe’s female impersonator], who deceived a great many of the audience and Larry Nicol, the trick cyclist…"[3]

Jason Wilson, in his history of the well-known Canadian concert party, the Dumbbells, singled out the Diamond Troupe as being one of the "notable concert parties of the British Expedition Forces"[4] – an assessment presaged in the 1919 edition of The Stage, where the Diamond Troupe, along with the Australian troupe, Anzac Coves, were praised for having earned their applause "… by legitimate artistic means, and not on account of the increased wartime popularity of khaki or blue".[5]

Formation of the Diamond Troupe

The Diamond Troupe was formed in April 1917 in Arras, France where the 29th Division’s headquarters and various details were billeted. There, amidst ruins and the sound of distant shelling, the first voice trials took place. Out of 60 candidates drawn from every unit in the Division, eight were initially selected. Most if not all troupe members had had some previous experience in the performing arts; and all had served either in the trenches or within striking distance of enemy guns.[6] One member, Pte. Neville Giordano (1892-1958) from Cambridge, had even been part of the Division's historic landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 25 April 1915.

The name “Diamond Troupe” was inspired by the 29th Division’s own logo, a red half-diamond, and by the tactical superiority of the diamond formation in a military advance.[7]

Troupe members

Maintaining a full cast was a persistent challenge for all concert troupes, given the movement of battalions and the ever-increasing casualty list.[8] While there is no evidence of fatalities among members of the Diamond Troupe, contemporary photographs and published cast lists do suggest some variation in the group’s composition.[9] The following table includes all individuals (musicians and stage performers) ever reported as troupe members:

| Name | Regiment/Regimental Number | Date joined 29th Division |

|---|---|---|

| Pte. Neville George Romolus Giordano (1892-1958) | Royal Army Medical Corps, No. 2105 | March 1915 |

| L/Cp. Robert James Stannard (1891-1960) | Royal Fusiliers, No. 11481 | November 1915 |

| Pte. William Threlfall (1895-1940) | Royal Army Medical Corps, No. 2140 | February 1916 |

| Pte. Alec [Alexander] Hill (1894-1969) | Middlesex Regiment, No. PS/2213 | May 1916 |

| Pte. H. Palmer | Middlesex Regiment | May 1916 |

| Corp. Frank [Francis] Pollard | Inniskilling Fusiliers, No. 28698 | July 1916 |

| Pte. Arthur Sykes (1891-1961) | Border Regiment, No. 23781 | July 1916 |

| Pte. Jock McKinley | King’s Own Scottish Borderers, No. 15263 | August 1916 |

| Pte. Hubert John Henry Holmes (1888-1972) | South Wales Borderers, No. 202467 | March 1917 |

| Pte. Larry [Lawrence] Nicol (1894-1968) | South Wales Borderers, No. 45781 | April 1917 |

| Pte. George Hangle (1884-?) | Labour Battalion, No. 193731 | May 1917 |

| Pte. H. McArthur | Border Regiment | May 1917 |

| Pte. J. Morris | Border Regiment | June 1917 |

| Corp. Eric John Dean (1892-1967) | Hampshire Regiment, No. 306627 | August 1917 |

| George Darnie[10] | ||

| Mark Meny[11] |

Supporting the stage performers were several "stage hands" whose responsibilities extended from lighting to costumes to carpentry. They included L/Cpl. Frank R. Williams (Scenic Artist), Privates J. Price, F. Ball and J. McKinnon (Electricians), Dr. Evans (Carpenter), Pte. W. Brinsley (Costumes), Pte. J. Ross (Engineer) and Pte. Wilson (Assistant).

Finally, no account of the Diamond Troupe would be complete without acknowledging its commanding officer, Lt. Col. Ernest Trevor Langebear Wright, DSO (1880-1965). A veteran of the Gallipoli landing, Wright assumed command of the troupe in August 1917, following the departure of its former commander, Major John Graham Gillam (1884-1965). Wright was an exceptional leader who possessed authority, organizational skills and the respect of those who served under him. It was he who organized the troupe’s singular performance in London in January 1918 (see below), foregoing his own home leave to supervise the event.

Performances

While no complete listing exists of all the Diamond Troupe's performances, certainly the most comprehensive can be found in Capt. Stair Gillon’s The Story of the 29th Division. A record of gallant deeds. His account, along with documentation now housed in public and private collections, reveals a busy schedule performed right across the Western Front—from Boulogne in the west, to Cambrai in the east.[12] [13]

Like their counterparts in other divisions, the Diamond Troupe was supported financially by the 29th Division. As a result, the revenues from admission fees typically went to charities such as the Division’s Benevolent Fund, which supported the families of soldiers and non-commissioned officers either killed in action or disabled. At most public performances, such as those held in 1918 in Saint-Omer, audiences had their choice of open or reserved seats, with officers paying double the amount paid by other ranks.

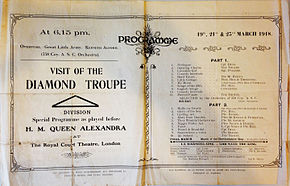

Royal Court Theatre, London

The troupe’s most publicized performance took place during the week of 21–26 January 1918 at London's Royal Court Theatre. Entitled "A Show from the Trenches", the troupe showcased their efforts to "alleviate the lot of the men in the trenches" while also raising money for the Benevolent Fund. Accounts of the shows, both matinee and evening, were widely reported in the press, particularly the matinee of Thursday the 24th, which was attended by the Queen Mother Alexandra and her daughter, Princess Victoria. An amusing personal account of the event is contained in Stannard’s diary. In it, he reported that the Queen "… sat in a box just opposite me … and although she sent a message after the show saying how greatly she had enjoyed it all she didn't appear to be enjoying herself a bit".[14]

In the end, the show was a great success, having netted the Benevolent Fund a profit of £750.[15] Audiences included the rich and famous, including what one newspaper described as "parties of stars”—renowned stage actresses, celebrities, and the wives of senior politicians and officers—who volunteered their time to sell programmes.[16] [17] According to the Daily Mail, many talent scouts were also to be seen.[18] The theatre manager even asked the troupe to extend their contract by another week and the Ministry of Munitions requested that they be allowed to tour various munition centers. In both cases the War Office refused, arguing that the troupe was needed back with the division.

-

Postcard advertisement for "A Show from the Trenches".

-

Pte. Arthur Sykes as Faust and Pte. Alec Hill as Mephistopheles.

-

A duet, "Mary from Dundee". With Pte. Jock McKinley and "Queenie" (Pte. William Threlfall). (Imperial War Museum).

-

Pte. J. Morris in a promotional photo from "A Show from the Trenches", London.

The repertoire

The London performances were representative of the troupe’s broader repertoire—an eclectic mixture of acrobatics, music and monologues, very much in line with the vaudeville performances of the time. The Royal Court Theatre programme highlighted a number of duets between the female impersonator, "Queenie" (played by William Threlfall), and troupe members Arthur Sykes, Alec Hill, and Jock McKinley. The program also included a trick cycling act by Larry Nicol; solo musical performances by Scottish comedian Frank Pollard; and several theatrical sketches and monologues by Neville Giordano.

Much of the troupe's musical repertoire included well-known, contemporary compositions such as W.T. Wrighton’s Sing me an English Song, Philip Braham’s We’ll have a Little Cottage (1917), Weatherly and Wood’s Roses of Picardy (1916), Thomas J. Hewitt’s Alone in Love’s Garden (1912), and Davy Burnaby and Gitz Rice's A Conscientious Objector (1917).

The repertoire also included original productions—designed, written and in some cases composed for the troupe itself. The troupe’s first commanding officer, Major John Graham Gillam, excelled at producing operatic scenes, many of which (such as Faust) Hill and Sykes would routinely play to great acclaim. Another key contributor to the troupe’s repertoire was officer Lancelot Cayley Shadwell, ASC, (1882-1963) who Gillon described as a “lyrical bard … [able to] supply the light, topical, frivolous comic matter, so dear to the average Briton”. Typical of this genre were two songs, In these Hard Times and 365 Days. Shadwell also set to music by Robert James Stannard, the Harlequin and Columbine scene, which Gillon described as “… probably the most finished production of the troupe”.[19]

-

A Show from the Trenches, Royal Court Theatre, London, 21-26 January 1918.

-

Undisclosed location in France, 19, 21, 23 March 1918 (Imperial War Museum).

-

New Theatre, Saint-Omer, France, 8 June 1918 (Imperial War Museum).

-

Grand Concert, Kiosque de la Grand'Place, Commune de Tubize, Belgium, 22 November 1918 (Imperial War Museum).

Song of the 29th Division

In 1917, Lancelot Cayley Shadwell wrote the lyrics to what would become the Divisional anthem, the Song of the 29th Division.[20] It is sung to music by Wilfred Ernest Sanderson (1878-1935) a composer, organist and, in all likelihood, associate of the troupe's music director, Robert Stannard. During the war, performances of the Song of the 29th Division were sung exclusively by baritone Alec [Alexander] Hill.

The wartime journalist and author, Sir Philip Armand Hamilton Gibbs, described the stirring effect the song had on those in the Division. There was, he said, “… a hush when the song was sung, for it brought back to some of the men who heard it the days of the battle in the Dardanelles and in the fields of the Somme or the quagmire of Flanders where the ghosts of brave comrades were.”[21]

Though all but forgotten today, the Song of the 29th Division was once a recognized tune, often performed at events honoring those who had served with the Division. In 1943, for example, the song was played at the funeral of Col. Robert Quentin Craufurd who served with the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front from 1914 to 1919.[22]

Lyrics to the Song of the 29th Division

From the Border vales and the Northern dales,

From the rolling wave-beat coast,

From South to North the lads stream forth,

Oh! we are the Army's boast!

And where there's a bitter fight to wage

On a field all rent and gory,

The whole world knows there the Red Sign goes,

Well famed in Britain's story.

Oh, this is the Song of the Twenty-Ninth

In the East and the West you'll find it;

There's never a fight where the Red Sign goes

But it leaves its mark behind it.In desert sands of alien lands

Sleep our bravest and our best;

There's a Turkish hill where the flowers wave still

O'er the graves where our dear lads rest.

And wherever the red war trail's agleam,

And the battle thunders waken,

There's a tale to be told of a soul of gold

Who trod Death's path unshaken.

Oh, this is the Song of the Twenty-Ninth

In the East and the West you'll find it;

There's never a fight where the Red Sign goes

But it leaves its mark behind it.With a roll of drum the Divisions come

Hot foot to the battle's blast;

When the good Red Sign swings into the line

Oh! There they'll fight to the last!

And the souls of those from the East and West,

Well famed in Britain's story,

March at our head with silent tread

To Honour and to Glory.

Oh, this is the Song of the Twenty-Ninth,"

On every field you'll find it;

For wherever the Red Triangle went

It left its mark behind it.

Lancelot Cayley Shadwell (1882-1963)

After the War

After the Armistice, the 29th Division was one of several divisions chosen to march into Germany to occupy the Rhine bridgehead. In January 1919, soldiers with more than two years of foreign service were given permission to take leave and apply for demobilization at their regimental depots. In his diary, Stannard noted that he and nine other members of the troupe were among the first to do so. They were soon followed by the others, although one or two, such as Queenie, remained in Germany to be absorbed into the few remaining concert troupes. By March, however, demobilization was in full swing and most units of the 29th were down to just a few officers.

The Diamond Troupe was typical of many concert parties in that its members, even before the war, had been active in the performing arts as singers, actors, or musicians. Not surprisingly, after returning to civilian life, many chose to pursue their artistic vocations—some full-time, some as an adjunct to more stable day jobs.

The troupe’s musical director, Robert J. Stannard, who as a boy attended Westminster Abbey Choir School and sang at the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, returned to Uxbridge and his career as an organist. In 1940, he moved to Frome in Somerset where he was appointed organist and choir master for St John's Church and head of music at the Frome Grammar School for Boys and Girls.

In July 1919 William Threlfall (Queenie) returned to Liverpool where he found work as a pianist with various dance bands. He played in gigs as far afield as the Isle of Man and Saarbrucken with groups such as the Estrella Quartette, Sam Lawson’s “Elite” Orchestra, and Jack Briggs and his Band. In 1926, Threlfall went to sea as a band musician—a career that would see him aboard many of the great White Star and Cunard transatlantic liners, from the RMS Baltic to the RMS Mauretania to eventually the RMS Aquitania. Ship manifests show him almost constantly at sea, with stops in Liverpool, Glasgow, Southampton, Boston, New York, Havana, and occasionally the Mediterranean. In 1938, ill health saw Threlfall return to Southampton. After a few months, he returned briefly to sea; but ultimately ceased travelling in February 1939. In 1940, at age 44, he died suddenly of a ruptured gastric ulcer.

Alec [Alexander] Hill, who performed in operas and operettas before the war, returned in 1919 to his home in Bolton, Lancashire. While his workdays were spent behind a desk, he sang professionally at weekends and evenings, well into the 1950s. With the support of his pianist wife, Margaret Eliza (née) Urmson, he continued performing Faust at the 1927 Blackpool Musical Festival, the 1934 Gounod's Grand Opera at Victoria Hall, Bolton and at Queen's Hall, Wigan in 1953. He performed at the Rothesay Pavilion in Bute, the Haddon Hall Hydro, Buxton, the Odeon in Llandudno and numerous other venues across Britain.

Glasgow-born Larry [Lawrence] Nicol adopted the stage name, Larry Kemble, and embarked on an active stage career as a comedic cyclist. In 1919, he married into a well-known theatrical family, the Loydalls, and for the next 30 years, performed at the Bristol Hippodrome, London Coliseum (for the 1928 Royal Variety Performance), Glasgow’s Alhambra and Empire Theatres, and the Stoll Theatre, Kingsway, among others. In 1940, Nicol was filmed in London, doing tricks on a very tall unicycle. See the full video on British Pathe.

Neville Giordano, the troupe’s only member to have participated in the initial Gallipoli landing, returned to acting under a stage name, Neville Gordon. In February 1920, the Cambridge Daily News praised his role as Lord Fancourt Babberley in "Charley’s Aunt"; and spoke highly of his recent successes in Stanley Houghton's (1881-1913) "Hindle Wakes" and "The Younger Generation".[23] By 1920, he was also filling engagements with the F.R. Benson Shakespearian Company.

Finally, Yorkshire-born Arthur Sykes returned to his home in Carlisle, Cumbria, where, for the next 40 years, he held the post of principal tenor at Carlisle Cathedral. During World War II, he, along with Kathleen Ferrier, Ena Mitchel and Albert Bettany formed a quartet that played to hospitals and camps across Scotland, the Midlands and North East.[24] At Sykes' funeral in 1961, the Dean of Carlisle Cathedral praised him as “… a man who used an outstanding voice to the end of his life for the glory of God and to the service of his fellow men….”[25]

Reunions

Given the Diamond Troupe’s reputation and success, it is all too easy to forget that as a performing unit, they existed for less than two years: from their first show under a “fine canvas theatre” in Proven in August/September 1917 to their last performance as victors in Wermelskirchen, Germany in December 1918. And then, as Gillon wrote, “the Diamond Troupe thus stole silently away…” It is not known how often troupe members kept in touch with one another after the war or to what extent they were called upon to join in activities associated with the 29th Division.

In 1921, the Division Association spearheaded an effort to keep servicemen in touch with their regimental associations. Their approach called for sending out small cards every month, each containing a calendar and a poem relating to the history of the Division. In February 1921, the card included Lancelot Cayley Shadwell’s lyrics to the Song of the 29th Division.[26] It is not known how long this practice was maintained.

On 25 April 1929—the fourteenth anniversary of the Gallipoli landing—the 29th Division Association held its twenty-first annual dinner at London’s Café Royal. There, Hill, Stannard, Palmer and Holmes were reunited to perform the Song of the 29th Division.[27] A newspaper report at the time described the event as a:

... remarkable gathering of distinguished sailors and soldiers… [whose most] inspiring moment came when Mr. Alec Hill sang the song of the 29th Division. He used to sing it out there in the war days, and [it] … has never, perhaps, been cherished by so many war leaders. Earl Jellicoe, Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, General Sir Ian Hamilton, and General Sir Aylmer Hunter Weston, among others at the top table, sang it with the infectious enthusiasm of youth.

References

- ^ Collins, Larry. "War Culture: WWI Theatre. Military History Monthly". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Collins, Larry. "War Culture: WWI Theatre. Military History Monthly". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Somerset Standard. "Looking Back: 'Honour to perform for the Queen in matinee show'". Frome Standard. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Jason (2012). Soldiers of Song: the Dumbells and other Canadian concert parties of the First World War. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- ^ Carson, Lionel (1919). "The Stage" Year Book. London: "The Stage" Offices. p. 35.

- ^ Royal Court Theatre. "A Show from the Trenches" Programme.

- ^ Gillon, Stair (1925). The Story of the 29th Division: A record of gallant deeds. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd. p. 102.

- ^ Collins, Larry. "War Culture: WWI Theatre. Military History Monthly". Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ Frederick Pollard was wounded in January 1916 at the Battle of Loos; Pte. Larry Nicol was wounded at St. Jean on 4 July 1917.

- ^ The only reference to the name George Darnie is found in a photograph donated to the Imperial War Museum in January 1934, by former Diamond Troupe member Eric John Dean.

- ^ The only reference to the name Mark Meny is found in a photograph donated to the Imperial War Museum in January 1934, by former Diamond Troupe member Eric John Dean.

- ^ Two important repositories of Diamond Troupe materials include London’s Imperial War Museum and the University of Bristol's Mander and Mitchenson (Theatre) Collection.

- ^ Performances were given at the following locations during 1917: Proven, Belgium (August/September); Berles-au-Bois, France (October/November); Cambrai, France (November); Péronne, France; and Wimereux, France (December). During 1918, performances were given in London from January 21-26; Abèle, Belgium (January/February); Poperinghe, Belgium (February); an unknown location in France on March 19, 21, 23; Steenvoorde, France; Vlamertinghe, Belgium; Boulogne, France; Wallon-Cappel, France; Saint-Omer, France on June 8; Hazebrouck, France (June, August); Roubaix, France (October); Tubize, Belgium on November 22; and in Wermelskirchen, Germany (December).

- ^ Somerset Standard. "Looking Back: Honour to perform for the Queen in matinee show". Frome Standard. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ Gillon, Stair (1925). The Story of the 29th Division: a record of gallant deeds. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd. p. 108.

- ^ "Diamond Troupe's Progress". The Times: 9. 23 January 1918.

- ^ At the matinee performance of Monday, 21 January, the "stars" included such well-known actresses as Doris Keane, Viola Tree, Gladys Cooper, Eva Moore and Renee Kelly.

- ^ Art Out of War. Daily Mail. 5 February 1918. p. 2.

- ^ Gillon, Stair (1925). The Story of the 29th Division: A record of gallant deeds. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd. p. 106.

- ^ The Song of the Twenty-Ninth Division with words by Lancelot Cayley Shadwell, the Music by Wilfred Sanderson. London: Boosey & Company. 1918.

- ^ Gillon, Stair (1925). The Story of the 29th Division: A record of gallant deeds. London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd. p. 109.

- ^ "Death of Prominent Berkhamsted Resident". The Bucks Herald: 6. 22 January 1943.

- ^ "Still Running". Cambridge Daily News. 14 August 1920.

- ^ "Death of Noted Singer". Cumberland News. 3 November 1961.

- ^ "Funeral of Mr. Arthur Sykes". Cumberland News. 10 November 1961.

- ^ "By the Way". Portsmouth Evening News: 4. 5 February 1921.

- ^ "Gallipoli Day Ceremony: Wreaths Lain at Cenotaph". The Courier and Advertiser: 6. 26 April 1929.

External links

- WAR CULTURE – WWI Theatre

- The British Army in the Great War: The 29th Division

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Gallipoli Expedition (1915–16)