The Purloined Letter

The Gift: A Christmas, New Year, and Birthday Present. Carey and Hart, Philadelphia, 1845. | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Detective fiction Short story |

| Publisher | The Gift for 1845 |

Publication date | December 1844 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (periodical) |

"The Purloined Letter" is a short story by American author Edgar Allan Poe. It is the third of his three detective stories featuring the fictional C. Auguste Dupin, the other two being "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" and "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt". These stories are considered to be important early forerunners of the modern detective story. It first appeared in the literary annual The Gift for 1845 (1844) and was soon reprinted in numerous journals and newspapers.

Plot summary

The unnamed narrator is discussing with the famous Parisian amateur detective C. Auguste Dupin some of his most celebrated cases when they are joined by the Prefect of the Police, a man known as G—. The Prefect has a case he would like to discuss with Dupin.

A letter has been stolen from the private sitting room of an unnamed female by the unscrupulous Minister D—. It is said to contain compromising information. D— was in the room, saw the letter, and switched it for a letter of no importance. He has been blackmailing his victim.

The Prefect makes two deductions with which Dupin does not disagree:

- 1.) The contents of the letter have not been revealed, as this would have led to certain circumstances that have not arisen. Therefore Minister D— still has the letter in his possession.

- 2.) The ability to produce the letter at a moment’s notice is almost as important as possession of the letter itself. Therefore he must have the letter close at hand.

The Prefect says that he and his police detectives have searched the Ministerial hotel where D— stays and have found nothing. They checked behind the wallpaper and under the carpets. His men have examined the tables and chairs with microscopes and then probed the cushions with needles but have found no sign of interference; the letter is not hidden in these places. Dupin asks the Prefect if he knows what he is looking for and the Prefect reads off a minute description of the letter, which Dupin memorizes. The Prefect then bids them good day.

A month later, the Prefect returns, still bewildered in his search for the missing letter. He is motivated to continue his fruitless search by the promise of a large reward, recently doubled, upon the letter's safe return, and he will pay 50,000 francs to anyone who can help him. Dupin asks him to write that check now and he will give him the letter. The Prefect is astonished but knows that Dupin is not joking. He writes the check and Dupin produces the letter. The Prefect determines that it is genuine and races off to deliver it to the victim.

Alone together, the narrator asks Dupin how he found the letter. Dupin explains the Paris police are competent within their limitations, but have underestimated who they are dealing with. The Prefect mistakes the Minister D— for a fool because he is a poet. For example, Dupin explains how an eight-year old boy made a small fortune from his friends at a game called "Odds and Evens." The boy was able to determine the intelligence of his opponents and play upon that to interpret their next move. He explains that D— knew the police detectives would have assumed that the blackmailer would have concealed the letter in an elaborate hiding place, and thus hid it in plain sight.

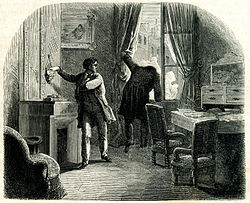

Dupin says he had visited the minister at his hotel. Complaining of weak eyes he wore a pair of green spectacles, the true purpose of which was to disguise his eyes as he searched for the letter. In a cheap card rack hanging from a dirty ribbon, he saw a half-torn letter and recognized it as the letter of the story's title. Striking up a conversation with D— about a subject in which the minister is interested, Dupin examined the letter more closely. It did not resemble the letter the Prefect described so minutely; the writing was different and it was sealed not with the "ducal arms" of the S— family, but with D—'s monogram. Dupin noticed that the paper was chafed as if the stiff paper was first rolled one way and then another. Dupin concluded that D— wrote a new address on the reverse of the stolen one, re-folded it the opposite way and sealed it with his own seal.

Dupin left a snuff box behind as an excuse to return the next day. Striking up the same conversation they had begun the previous day, D— was startled by a gunshot in the street. While he went to investigate, Dupin switched D—'s letter for a duplicate.

Dupin explains that he left a duplicate to ensure his ability to leave the hotel without D— suspecting his actions. As a political supporter of the Queen and old enemy of the Minister, Dupin also hopes that D— will try to use the power he no longer has, to his political downfall, and at the end be presented with an insulting note that implies Dupin was the thief: Un dessein si funeste, S'il n'est digne d'Atrée, est digne de Thyeste (If such a sinister design isn't worthy of Atreus, it is worthy of Thyestes). (see Atree et Thyeste on french wikipedia)

Analysis

The epigraph "Nihil sapientiae odiosius acumine nimio" (Nothing is more hateful to wisdom than excessive cleverness) attributed by Poe to Seneca was not found in Seneca's known work.

Dupin is not a professional detective. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," Dupin takes up the case for amusement and refuses a financial reward. In "The Purloined Letter," however, Dupin undertakes the case for financial gain. He is not motivated by pursuing truth, emphasized by the lack of information about the contents of the purloined letter.[1] Dupin's innovative method to solve the mystery is by trying to identify with the criminal.[2] The Minister and Dupin have equally matched minds, combining skills of mathematician and poet,[3] and their battle of wits is threatened to end in stalemate. Dupin wins because of his moral strength: the Minister is "unprincipled," a blackmailer who obtains power by exploiting the weakness of others.[4]

Poe may have identified with both Dupin and D—. Like Poe, these two characters command both the power of analysis and a strong imagination.[3]

"The Purloined Letter" completes Dupin's tour of different settings. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" he travels through city streets; in "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" he is in the wide outdoors; in "The Purloined Letter" he is in an enclosed private space.[5] French linguist Jean-Claude Milner offered in Détections fictives , Le Seuil, collection « Fictions & Cie », 1985, supporting evidence that Dupin and D— are brothers, based on the final reference to Atreus and his twin brother, Thyestes.

Literary significance and criticism

In May 1844 Poe wrote to James Russell Lowell that he considered it "perhaps the best of my tales of ratiocination" just before its first publication. Of Poe's three tales of ratiocination, "The Purloined Letter" is generally considered the best.[3][6] When it was republished in the 1845 edition of The Gift, the editor called it "one of the aptest illustrations which could well be conceived of that curious play of two minds in one person."[7]

The story was used by the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and the philosopher Jacques Derrida to present opposing interpretations: Lacan's at once structuralist, Derrida's mystical, depending on deconstructive chance.[8] The two exchanged a series of letters concerning the nature of desire.[citation needed]

Publication history

This story first appeared in The Gift: A Christmas and New Year's Present for 1845, published in December, 1844 in Philadelphia. Poe earned $12 for its first printing.[9] It was later included in the 1845 collection Tales By Edgar A. Poe.

Adaptations

In 1980 the story was adapted as a Sherlock Holmes episode.[1]

In 1995 the story was adapted for an episode of the children's television program, Wishbone. The episode was called 'The Pawloined Paper.'

See also

References

- ^ Whalen, Terance. "Poe and the American Publishing Industry" collected in A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe, J. Gerald Kennedy, editor. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-512150-3 p. 86

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 155. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ^ a b c Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9 p. 421

- ^ Garner, Stanton. "Emerson, Thoreau, and Poe's 'Double Dupin'," collected in Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu, edited by Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1990. p. 141. ISBN 0-9616449-2-3

- ^ Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997). The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. Johns Hopkins University Press, 69. ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6

- ^ Cornelius, Kay. "Biography of Edgar Allan Poe," collected in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, Harold Bloom, ed. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002. p. 33 ISBN 0-7910-6173-6

- ^ Phillips, Mary E. Edgar Allan Poe: The Man. Volume II. Chicago: The John C. Winston Co., 1926. p. 930–931

- ^ [The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud, University of Chicago Press, Jacques Derrida, 1987, pg. 182]

- ^ Ostram, John Ward. "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards" in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. p. 40

External links

- The Purloined Letter, online at Ye Olde Library

- The Purloined Letter at American Literature

- Full text on PoeStories.com with hyperlinked vocabulary words

- Dept. of English, fju.edu analyzes the story with the help of diagrams

- Cliffs Notes on Poe's Short Stories has a page on The Purloined Letter