Tiled Kiosk

Çinili Köşk | |

Tiled Kiosk | |

| Established | 1953 |

|---|---|

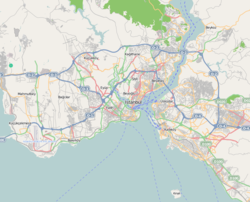

| Location | Alemdar Cad. Osman Hamdi Bey Yokuşu Sok. 34122, Gülhane Fatih, Istanbul |

| Type | Art museum |

| Website | www |

The Tiled Kiosk (Template:Lang-tr) is a pavilion set within the outer walls of Topkapı Palace and dates from 1472 as shown on the tile inscript above the main entrance.[1][2] It was built by the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II as a pleasure palace or kiosk. It is located in the most outer parts of the palace, next to Gülhane Park. It was also called Glazed Kiosk (Sırça Köşk).[3]

Architecture

The building has a Greek cross shaped groundplan and two storeys high,[4] although since the building straddles a declivity, only one floor is visible from the main entrance. The exterior glazed bricks show a Central Asian influence, especially from the Bibi-Khanym Mosque in Samarkand. The square, axial plan represents the four corners of the world and symbolizes, in architectural terms, the universal authority and sovereignty of the Sultan. As there is no Byzantine influence, the building is ascribed to an unknown Persian architect.[5] The stone-framed brick and the polygonal pillars of the façade are typical of Persia. A grilled gate leads to the basement. Two flights of stairs above this gate lead to a roofed colonnaded terrace. This portico was rebuilt in the 18th century. The great door in the middle, surrounded by a tiled green arch, leads to the vestibule and then to a loftily domed court. The three royal apartments are situated behind, with the middle apartment in apsidal form.[6]

These apartments look out over the park to the Bosphorus. The network of ribbed vaulting suggests Gothic revival architecture, but it actually adds weight to the structure instead of sustaining it. The blue-and-white tiles on the wall are arranged in hexagons and triangles in the Bursa manner.[7] Some show delicate patterns of flowers, leaves, clouds or other abstract forms. The white plasterwork is in the Persian manner. On both wings of the domed court are eyvans, vaulted recesses open on one side.

Museum

It was used as the Imperial Museum (Template:Lang-ota, Template:Lang-tr) between 1875 and 1891.[8] In 1953, it was opened to the public as a museum of Turkish and Islamic art, and was later incorporated into the Istanbul Archaeology Museums.

The pavilion contains many examples of İznik tiles and Seljuk pottery and now houses the Museum of Islamic Art.

Admission

The museum is closed on Mondays. Opening hours are 9:00 to 17:00.

References

- ^ "History". Istanbul Archaeological Museums. Retrieved 3013-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru (1991). Architecture, ceremonial, and power: The Topkapı Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 213. ISBN 0-262-14050-0.

- ^ Davis, pg. 266

- ^ Fanny Davis. Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul. 1970. pg. 266-267. ASIN B000NP64Z2

- ^ Necipoğlu, pg. 214

- ^ Necipoğlu, pg. 216

- ^ Davis, pg. 267

- ^ Davis, pg. 268

Literature

- Sir Banister Fletcher. A History of Architecture. Boston: Butterworths, 1987. ISBN 0-408-01587-X. NA200.F63 1987. discussion p611

- John Julius Norwich, ed. Great Architecture of the World. New York: Random House, 1975. ISBN 0-394-49887-9. NA200.G76. discussion, facade photo, p140.

- John D. Hoag. Islamic Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1977. ISBN 0-8109-1010-1. LC 76-41805. NA380.H58. plan drawing, fig427, p324. Goodwin, 1971.