Titius–Bode law

The Titius–Bode law (sometimes termed just Bode's law) is a hypothesis that the bodies in some orbital systems, including the Sun's, orbit at semi-major axes in a function of planetary sequence. The formula suggests that, extending outward, each planet would be approximately twice as far from the Sun as the one before. The hypothesis correctly anticipated the orbits of Ceres (in the asteroid belt) and Uranus, but failed as a predictor of Neptune's orbit and has since been discredited further. It is named for Johann Daniel Titius and Johann Elert Bode.

Formulation

The law relates the semi-major axis of each planet outward from the Sun in units such that the Earth's semi-major axis is equal to 10:

where with the exception of the first step, each value is twice the previous value. There is another representation of the formula: where . The resulting values can be divided by 10 to convert them into astronomical units (AU), resulting in the expression

for For the outer planets, each planet is predicted to be roughly twice as far from the Sun as the previous object.

Paradoxical origin and subsequent course

The first mention of a series[citation needed] approximating Bode's Law is found in David Gregory's The Elements of Astronomy, published in 1715. In it, he says, "...supposing the distance of the Earth from the Sun to be divided into ten equal Parts, of these the distance of Mercury will be about four, of Venus seven, of Mars fifteen, of Jupiter fifty two, and that of Saturn ninety five."[1] A similar sentence, likely paraphrased from Gregory,[1] appears in a work published by Christian Wolff in 1724.

In 1764, Charles Bonnet said in his Contemplation de la Nature that, "We know seventeen planets that enter into the composition of our solar system [that is, major planets and their satellites]; but we are not sure that there are no more."[1] To this, in his 1766 translation of Bonnet's work, Johann Daniel Titius added two of his own paragraphs, at the bottom of page 7 and at the beginning of page 8. Of course, the new interpolated paragraph is not found in Bonnet's original text, nor in translations of the work into Italian and English.

There are two parts to Titius's intercalated text. The first part explains the succession of planetary distances from the Sun:

Take notice of the distances of the planets from one another, and recognize that almost all are separated from one another in a proportion which matches their bodily magnitudes. Divide the distance from the Sun to Saturn into 100 parts; then Mercury is separated by four such parts from the Sun, Venus by 4+3=7 such parts, the Earth by 4+6=10, Mars by 4+12=16. But notice that from Mars to Jupiter there comes a deviation from this so exact progression. From Mars there follows a space of 4+24=28 such parts, but so far no planet was sighted there. But should the Lord Architect have left that space empty? Not at all. Let us therefore assume that this space without doubt belongs to the still undiscovered satellites of Mars, let us also add that perhaps Jupiter still has around itself some smaller ones which have not been sighted yet by any telescope. Next to this for us still unexplored space there rises Jupiter's sphere of influence at 4+48=52 parts; and that of Saturn at 4+96=100 parts.

In 1772, Johann Elert Bode, aged only twenty-five, completed the second edition of his astronomical compendium Anleitung zur Kenntniss des gestirnten Himmels (“Manual for Knowing the Starry Sky”), into which he added the following footnote, initially unsourced, but credited to Titius in later versions (in a posthumous Bode's memoir can to be fund a reference to Titius with clear recognition of their priority):[2]

This latter point seems in particular to follow from the astonishing relation which the known six planets observe in their distances from the Sun. Let the distance from the Sun to Saturn be taken as 100, then Mercury is separated by 4 such parts from the Sun. Venus is 4+3=7. The Earth 4+6=10. Mars 4+12=16. Now comes a gap in this so orderly progression. After Mars there follows a space of 4+24=28 parts, in which no planet has yet been seen. Can one believe that the Founder of the universe had left this space empty? Certainly not. From here we come to the distance of Jupiter by 4+48=52 parts, and finally to that of Saturn by 4+96=100 parts.

These both statements, for all their particular typology and the radii of the orbits, seem to stem from an antique cossist.[3] In fact, many precedents have been finding up to the seventeenth century. Titius was a disciple of the German philosopher Christian Freiherr von Wolf (1679-1754), and the second part of the inserted text in the Bonnet's work is also literally founded in a von Wolf's work dated in 1723, Vernünftige Gedanken von den Wirkungen der Natur. That's why, in twentieth century literature about Titius–Bode law, usually is assigned as authorship the German philosopher; if so, Titius could learn from him. Another reference, older than before, is written by James Gregory in 1702, in his Astronomiae physicae et geometricae elementa, where the succession of planetary distances 4, 7, 10, 16, 52 and 100 becomes a geometric progression of ratio 2. This is the nearest Newtonian formula, which is also contained in Benjamin Martin and Tomàs Cerdà himself many years before the German publication of Bonnet's book.

Titius and Bode hoped that the law would lead to the discovery of new planets. But it really was not. The Uranus and Ceres discovery rather contributed to the fame of the Titius–Bode law, but not around Neptune and Pluto's discovery, just because both are excluded. However, it is applied to the satellites and even currently to the extrasolar planets.

When originally published, the law was approximately satisfied by all the known planets—Mercury through Saturn—with a gap between the fourth and fifth planets. It was regarded as interesting, but of no great importance until the discovery of Uranus in 1781, which happens to fit neatly into the series. Based on this discovery, Bode urged a search for a fifth planet. Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt, was found at Bode's predicted position in 1801. Bode's law was then widely accepted until Neptune was discovered in 1846 and found not to satisfy Bode's law. Simultaneously, the large number of known asteroids in the belt resulted in Ceres no longer being considered a planet at that time. Bode's law was discussed as an example of fallacious reasoning by the astronomer and logician Charles Sanders Peirce in 1898.[4]

The discovery of Pluto in 1930 confounded the issue still further. Although nowhere near its position as predicted by Bode's law, it was roughly at the position the law had predicted for Neptune. However, the subsequent discovery of the Kuiper belt, and in particular of the object Eris, which is more massive than Pluto yet does not fit Bode's law, have further discredited the formula.[5]

Titius–Bode law remains a solid and convincing theoretical explanation of their physical meaning, and is not considered as a numerical device. Its history has always been linked as more soup than substance. How can it be compared to the Hipparchus's work in respect to the planetary distances, those of Kepler regarding the orbit of Mars, the discovery of Neptune, the calculation of an event, those of an orbit starting by only three positions, or the explanation about the Mercury's perihelion deviation? However, it is usually more cited.

An explanation that could be earlier than Titius-Bode Law[6]

The Jesuit Tomàs Cerdà (1715-1791) gave a famous astronomy course in Barcelona in 1760, at the Royal Chair of Mathematics of the College of Sant Jaume de Cordelles (Imperial and Royal Seminary of Nobles of Cordellas). From the original manuscript preserved in the Royal Academy of History in Madrid, Lluís Gasiot remade Tratado de Astronomía from Cerdá, published in 1999, and which is based on Astronomiae physicae from James Gregory (1702) and Philosophia Britannica from Benjamin Martin (1747). In the Cerdàs's Tratado appears the planetary distances obtained from the periodic times applying the Kepler's third law, with an accuracy of 10−3. Taking as reference the distance from Earth as 10 and rounding to whole, can be established the geometric progression [(Dn x 10) - 4] / [(Dn-1 x 10) - 4] = 2, from n=2 to n=8. And using the circular uniform fictitious movement to the Kepler's Anomaly, it may be obtained Rn values corresponding to each planet's radios, which can be obtained the reasons rn = (Rn - R1) / (Rn-1 - R1) resulting 1.82; 1.84; 1.86; 1.88 and 1.90, which rn = 2 - 0.02 (12 - n) that is the ratio between Keplerian succession and Titus-Bode Law, which would be a casual numerical coincidence. The reason is close to 2, but really increases harmonically from 1.82.

The planet's average speed from n=1 to n=8 decreases when moving away the Sun and differs from uniform descent in n=2 to recover from n=7 (orbital resonance).

Data

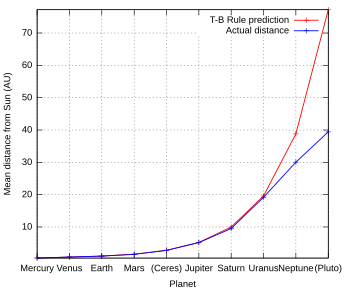

The Titius–Bode law predicts planets will be present at specific distances in astronomical units, which can be compared to the observed data for several planets and dwarf planets in the Solar System:

| k | T–B rule distance (AU) | Planet | Semimajor axis (AU) | Deviation from prediction1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.4 | Mercury | 0.39 | −3.23% |

| 1 | 0.7 | Venus | 0.72 | +3.33% |

| 2 | 1.0 | Earth | 1.00 | 0.00% |

| 4 | 1.6 | Mars | 1.52 | −4.77% |

| 8 | 2.8 | Ceres2 | 2.77 | −1.16% |

| 16 | 5.2 | Jupiter | 5.20 | +0.05% |

| 32 | 10.0 | Saturn | 9.55 | −4.45% |

| 64 | 19.6 | Uranus | 19.22 | −1.95% |

| 128 | 38.8 | Neptune | 30.11 | −22.40% |

| Orcus3 | 39.17 | +0.96% | ||

| Pluto3 | 39.54 | +1.02% | ||

| Haumea3 | 43.22 | +11.39% | ||

| Quaoar3 | 43.40 | +11.87% | ||

| 256 | 77.8 | 2007 OR103 | 66.85 | −14.07% |

| Eris3 | 67.78 | −12.9% | ||

| 512 | 154.00 | 2000 CR1053 | 230.12 | +49.4% |

| 1024 | 307.6 | 2010 GB1743 | ~351.0 | +14% |

| 2048 | 614.8 | Sedna3 | 506.2 | −17.66% |

| Planet Nine (hypothetical) |

~665[7] | +8% |

1 For large k, each Titius–Bode rule distance is approximately twice the preceding value. Hence, an arbitrary planet may be found within −25% to +50% of one of the predicted positions. For small k the predicted distances do not fully double, so the range of potential deviation is smaller. Note the semimajor axis is proportional to the 2/3 power of the orbital period. For example, planets in a 2:3 orbital resonance (such as plutinos relative to Neptune) will vary in distance by (2/3)2/3 = -23.69% and +31.04% relative to one another.

2 Ceres, now classified as a dwarf planet, was considered a small planet from 1801 until the 1860s. It orbits near the middle of the asteroid belt, most of whose objects fall in three bands between -25% and +18% of the Titius-Bode rule distance (2.06 to 2.5 AU, 2.5 to 2.82 AU, 2.82 to 3.28 AU), which are separated by Kirkwood gaps representing 3:1, 5:2, and 2:1 resonances with Jupiter.

3 Pluto was considered a planet from 1930 to 2006, when it was reclassified as a dwarf planet. Aside from the hypothetical Planet Nine, none of the small objects beyond Neptune currently qualifies as a planet.

Theoretical explanations

There is no solid theoretical explanation of the Titius–Bode law, but if there is one it is possibly a combination of orbital resonance and shortage of degrees of freedom: any stable planetary system has a high probability of satisfying a Titius–Bode-type relationship. Since it may simply be a mathematical coincidence rather than a "law of nature", it is sometimes referred to as a rule instead of "law".[8] However, astrophysicist Alan Boss states that it is just a coincidence, and the planetary science journal Icarus no longer accepts papers attempting to provide improved versions of the law.[5]

Orbital resonance from major orbiting bodies creates regions around the Sun that are free of long-term stable orbits. Results from simulations of planetary formation support the idea that a randomly chosen stable planetary system will likely satisfy a Titius–Bode law.[9]

Dubrulle and Graner[10][11] have shown that power-law distance rules can be a consequence of collapsing-cloud models of planetary systems possessing two symmetries: rotational invariance (the cloud and its contents are axially symmetric) and scale invariance (the cloud and its contents look the same on all scales), the latter being a feature of many phenomena considered to play a role in planetary formation, such as turbulence.

Lunar systems and other planetary systems

There is a decidedly limited number of systems on which Bode's law can presently be tested. Two of the solar planets have a number of big moons that probably have formed in a process similar to that which formed the planets. The four big satellites of Jupiter and the biggest inner satellite, Amalthea, cling to a regular, but non-Titius–Bode, spacing, with the four innermost locked into orbital periods that are each twice that of the next inner satellite. The big moons of Uranus also have a regular non-Titius–Bode spacing.[12] However, according to Martin Harwit, "a slight new phrasing of this law permits us to include not only planetary orbits around the Sun, but also the orbits of moons around their parent planets."[13] The new phrasing is known as Dermott's law.

Of the recent discoveries of extrasolar planetary systems, few have enough known planets to test whether similar rules apply to other planetary systems. An attempt with 55 Cancri suggested the equation a = 0.0142 e 0.9975 n, and predicts for n = 5 an undiscovered planet or asteroid field at 2 AU.[14] This is controversial.[15] Furthermore, the orbital period and semimajor axis of the innermost planet in the 55 Cancri system have been significantly revised (from 2.817 days to 0.737 days and from 0.038 AU to 0.016 AU respectively) since the publication of these studies.[16]

Recent astronomical research suggests that planetary systems around some other stars may fit Titius–Bode-like laws.[17][18] Bovaird and Lineweaver[19] applied a generalized Titius–Bode relation to 68 exoplanet systems that contain four or more planets. They showed that 96% of these exoplanet systems adhere to a generalized Titius–Bode relation to a similar or greater extent than the Solar System does. The locations of potentially undetected exoplanets are predicted in each system.

Subsequent research managed to detect five planet candidates from predicted 97 planets from the 68 planetary systems. The study showed that the actual number of planets could be larger. The occurrence rate of Mars and Mercury sized planets are currently unknown, so many planets could be missed due to their small size. Other reasons were accounted to planet not transiting the star or the predicted space being occupied by circumstellar disks. Despite this, the number of planets found with Titius–Bode law predictions were still lower than expected.[20]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Dawn: Where Should the Planets Be? The Law of Proportionalities".

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (26 June 1992). "Bodes' Law and the Discovery of Ceres". Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo "Giuseppe S. Vaiana". Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ The cossists were experts in calculations of all kinds and were employed by merchants and businessmen to solve complex accounting problems. Their name derives from the Italian word cosa, meaning “thing”, because they used symbols to represent an unknown quantity, similar to the way mathematicians use x today. All professional problem-solvers of this era invented their own clever methods for performing calculations and would do their utmost to keep these methods secret in order to maintain their reputation as the only person capable of solving a particular problem.

- ^ Pages 194–196 in

- Peirce, Charles Sanders, Reasoning and the Logic of Things, The Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898, Kenneth Laine Ketner, ed., intro., and Hilary Putnam, intro., commentary, Harvard, 1992, 312 pages, hardcover (ISBN 978-0674749665, ISBN 0-674-74966-9), softcover (ISBN 978-0-674-74967-2, ISBN 0-674-74967-7) HUP catalog page.

- ^ a b Alan Boss (October 2006). "Ask Astro". Astronomy. 30 (10): 70.

- ^ Dr. Ramon Parés. Distancias planetarias y ley de Titius-Bode (Historical essay). www.ramonpares.com

- ^ Renu Malhotra; Kathryn Volk; Xianyu Wang (9 March 2016). "Corralling a distant planet with extreme resonant Kuiper belt objects" (PDF).

- ^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2007). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (Second ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 716–717. ISBN 0-8053-0402-9.

- ^ Wayne Hayes; Scott Tremaine (October 1998). "Fitting Selected Random Planetary Systems to Titius–Bode Laws" (PDF). Bibcode:1998Icar..135..549H. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5999.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ F. Graner; B. Dubrulle (1994). "Titius-Bode laws in the solar system. Part I: Scale invariance explains everything". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282: 262–268. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..262G.

- ^ B. Dubrulle; F. Graner (1994). "Titius–Bode laws in the solar system. Part II: Build your own law from disk models". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282: 269–276. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..269D.

- ^ Cohen, Howard L. "The Titius-Bode Relation Revisited". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Harwit, Martin. Astrophysical Concepts (Springer 1998), pages 27–29.

- ^ Arcadio Poveda; Patricia Lara (2008). "The Exo-Planetary System of 55 Cancri and the Titus-Bode Law" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica (44): 243–246.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Ivan Kotliarov (21 June 2008). "The Titius-Bode Law Revisited But Not Revived". arXiv:0806.3532 [physics.space-ph].

- ^ Rebekah I. Dawson; Daniel C. Fabrycky (2010). "Title: Radial velocity planets de-aliased. A new, short period for Super-Earth 55 Cnc e". Astrophysical Journal. 722: 937–953. arXiv:1005.4050. Bibcode:2010ApJ...722..937D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/722/1/937.

- ^ "The HARPS search for southern extra-solar planets" (PDF). 23 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010. Section 8.2: "Extrasolar Titius-Bode-like laws?"

- ^ P. Lara, A. Poveda, and C. Allen. On the structural law of exoplanetary systems. AIP Conf. Proc. 1479, 2356 (2012); doi:10.1063/1.4756667

- ^ Timothy Bovaird; Charles H. Lineweaver (2013). "Title: Exoplanet predictions based on the generalized Titius–Bode relation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. arXiv:1304.3341. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.tmp.2080B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1357.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bibcode (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ http://arxiv.org/abs/1405.2259

Further reading

- The ghostly hand that spaced the planets New Scientist 9 April 1994, p13

- Plants and Planets: The Law of Titius-Bode explained by H.J.R. Perdijk

- Distancias planetarias y ley de Titius-Bode (Spanish) by Dr. Ramon Parés. http://media.wix.com/ugd/61b5e4_d5cf415763b44680806a8431ba375db2.pdf