Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius

| |

| |

| Established | ±1070 |

|---|---|

| Location | Keizer Karelplein 6, Maastricht, Netherlands |

| Director | Sigismund Tagage (treasurer) |

| Website | www.sintservaas.nl |

The Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius is a museum of religious art and artifacts inside the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht, Netherlands.

History

The treasure of the church of Saint Servatius was put together over many centuries. One of the oldest pieces (today non-existent) was a reliquary in the shape of a triumphal arch, donated by Einhard (biographer of Charlemagne and abbot of Saint Servatius) in the 9th century. In the 11th century a custodian ('custos') was put in charge of the church's already seizable treasure.

(Blokboek van St Servaas, ±1460)

During the late Middle Ages the number of relics further increased and a septennial pilgrimage ('Heiligdomsvaart') was instigated, which attracted tens of thousands of pilgrims. At these occasions, the church's main relics were shown to the pilgrims gathered on Vrijthof square from the dwarf gallery.[1] In 1579, the church treasure suffered badly during the Sack of Maastricht by the Spanish troops led by the Duke of Parma. In 1634, under the threat of war, the treasure was brought to Liège, where it remained for twenty years.

After the conquest of Maastricht by the French in 1794, the chapter of Saint Servatius was made to pay heavy war taxes. In order to pay these taxes gold and silver artefacts from the church treasure were melted down or sold. In 1798 the chapter was dissolved. A few important pieces had been brought into safety by the canons, some of which were given back after the church was restored to the religious service in 1804, but other pieces could not be retrieved. Some of the church's former treasures can now be found in museums and libraries around the world, such as the National Library of the Netherlands[2] in The Hague, the Royal Museums of Art and History[3][4] in Brussels, the Musée du Louvre[5][6] in Paris, the Kunstgewerbemuseum[7] in Berlin, the Alte Pinakothek[8] in Munich, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe[9] in Hamburg, the Victoria and Albert Museum[10] in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art[11] and The Morgan Library & Museum[12] in New York. The present treasure of the Basilica of Saint Servatius therefore, is much smaller than it once used to be.

The building

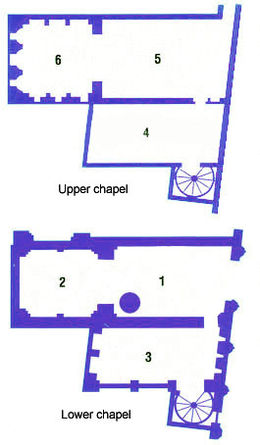

In 1340 it was reported that the treasure of the church was kept in a dark vaulted room on the lower floor of what is called the double chapel. The double chapel is one of the oldest surviving parts of the church and dates back to the 11th century. It was built adjacent to the northern transept and can only be accessed via the cloisters. This seems to have been the permanent location of the treasury until 1873, when it moved to the former refectory and chapter school.

After the restoration of the double chapel in 1982, the treasury was once again housed in its original location. The treasury now occupies both floors of the double chapel and a side room on each level. The basement floor with archaeological excavations has been made accessible. The entrance to the treasury, via the East wing of the cloisters, is on Keizer Karelplein, which is also the main entrance to the church.

The collection

The treasure of the Basilica of Saint Servatius traditionally consists of four parts: 1. the so-called Servatiana, objects traditionally associated with the life of Servatius, 2. relics and reliquaries, 3. liturgical implements and 4. ancient fabrics. The church's art collection and various archaeological finds are not part of the treasure but are also exhibited in the museum.

Servatiana

- The key of Saint Servatius: decorative key, one of the attributes of the saint, silver (early 9th century).[13]

- Pectoral cross of Saint Servatius: silver and golden cross (wooden core), with enamel and gemstones (10th or 11th century), a gift to the church from the duke of Bavaria.[14]

- The cup of Saint Servatius: millefiori glass, Roman (1st century).[15]

- The Crozier of Saint Servatius: wooden staff with ivory crook (12th century).[16]

- Portable altar of Saint Servatius: green serpentine stone with silver ornaments (12th century).[17]

Reliquaries

- The 'Noodkist': the reliquary shrine of Saint Servatius, an oak wooden chest, covered with gilded copper and decorated with enamel, vernis brun, cabochons and filigree (±1160). The 'Noodkist' was originally positioned on the main choir of the church and was accompanied by four panels, that in 1843 were sold and are now in the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels.

- The portrait bust of Saint Servatius: reliquary bust containing the skull of the saint, donated by Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma after the Sack of Maastricht (1579) in which the original bust was largely lost.

- Another important piece is the tall patriarchal cross with relics of the True Cross, made by the Maastricht silversmith Master Ulrich Peters, around 1490.

Liturgical implements

This part of the treasure suffered most during the French period (1794-1814). Many chalices, patens, monstrances and other liturgical objects made of gold or silver were melted down in order to pay the war taxes that the French demanded from the canons. However, a few liturgical vessels from the Middle Ages survived and quite a few from the Baroque period (notably some Maastricht silver pieces) are still in the collection.

Textiles

The medieval textiles collection of the Basilica of Saint Servatius is counted among the most important of its kind.[18] From 1989 till 1991 the textiles were carefully restored and documented by specialists from the Swiss Abegg-Stiftung[19] in Riggisberg. Among the best pieces in the collection are the so-called albe of Saint Servatius[20] and the robe of Monulph.[21] Furthermore, there is an extensive collection of early-Medieval woven silks (some dating back to the 7th century) from Constantinople,[22] Egypt[23] and Central Asia[24] and various medieval woven materials from the Meuse-Rhine area,[25] Spain,[26] Italy[27] and the Middle East.[28]

Art collection

The art collection of the Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius consists of a modest collection of paintings, prints, illuminated manuscripts, wood carving, stone sculptures, alabaster and ivory carving, enamels, and gold and silver smithing.

Archaeology

Archaeological excavations took place in the double chapel in 1981-82. Underneath the ground level floor of the Sacrarium inferior canons' grave stones were found, some dating back to the 13th century. Also, parts of walls were excavated that at the time were interpreted as the remains of a Carolingian polygonal church.[29] As it turned out, the walls belonged to polygonal transept arms of a 10th or 11th century church.[30] These remains can be seen in the basement underneath the treasury. Part of the archaeological collection is on display in the lapidarium in the eastern crypt. An important find was the 1086 funeral cross of Humbert, who was provost of the chapter of Saint Lambert's Cathedral in Liège and Saint Servatius in Maastricht. It was he who had the double chapel built which is today the church treasury.

-

Interior lower chapel

-

Key of St Servatius

-

Crozier of St Servatius

-

Pectoral cross

-

Reliquary chest ('Noodkist')

-

Portrait bust St Servatius

-

Patriarchal cross

-

Reliquary tablet

-

Ivory reliquary

-

Silk cloth

Bibliography

- Koldeweij, A.M., Der gude Sente Servas. Assen/Maastricht, 1985

- Kroos, R., Der Schrein des heiligen Servatius in Maastricht und die vier zugehörigen Reliquiare in Brüssel. Munich, 1985

- Stauffer, A., Die mittelalterlichen Textilien von St. Servatius in Maastricht. Bern, 1991

- Tagage, S., & various photographers, Kunstschatten uit de St.-Servaas. Maastricht, 1976

- Ubachs, P.J.H., and I.M.H. Evers, Historische Encyclopedie Maastricht. Zutphen, 2005

- Van Cauteren, J., and others, Schatkamers uit het Zuiden. Utrecht, 1985

References

- ^ Koldeweij, pp.197-207

- ^ Van Cauteren, p. 150-152

- ^ Kroos, pp. 242-251, 392-394

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 256-257

- ^ Van Cauteren, p. 151

- ^ Stauffer, p. 50

- ^ Stauffer, p.50

- ^ Van Cauteren, p. 156-158

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 65-66, 154-156

- ^ Collection V&A, Londen

- ^ Stauffer, p. 50

- ^ Koldeweij, p. 196

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 61-131

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 173-196

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 219-239

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 132-144

- ^ Koldeweij, pp. 239-243

- ^ Hans Christoph Ackermann (1991): "Diese Sammlung von Reliquienstoffen gehört zu den bedeutendsten Gruppen mittelalterlicher Textilien." (Stauffer, p.7)

- ^ See German Wikipedia: Abegg-Stiftung

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue number 7A

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue number 96

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 1, 2, 10-14, 35-49

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 28, 32, 33

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 3, 6, 8, 23-26, 30, 34, 53-57, 64, 106-110, 122, 151

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 100-105, 112, 114, 132, 134, 140

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 50, 51, 58, 59, 65-91, 96-99, 120, 121

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 16, 111, 113, 115-119, 123-129, 131

- ^ Stauffer, catalogue numbers 9, 27, 29, 31

- ^ De Sint Servaas (tweemaandelijks restauratiebulletin), 1982-1, pp. 5-7

- ^ E. den Hartog, Romanesque Sculpture in Maastricht. Maastricht, 2002, p. 6