Bowring Treaty

| Treaty of Friendship and Commerce between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Siam | |

|---|---|

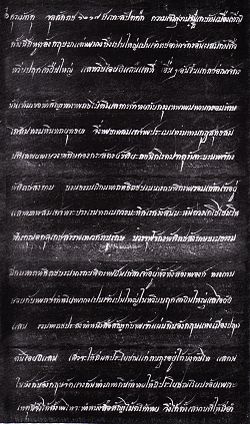

Thai version of the Treaty, written on Thai black books, prior to being sent to Great Britain to be affixed with the Royal seal. | |

| Type | Treaty |

| Signed | 18 April 1855 |

| Location | Bangkok, Siam |

| Parties | |

| Language | Thai and English |

| Full text | |

The Bowring Treaty was a treaty signed between the British Empire and the Kingdom of Siam on 18 April 1855. The treaty had the primary effect of liberalising foreign trade in Siam, and was signed by five Siamese plenipotentiaries (amongst them Wongsa Dhiraj Snid, one of the King's half-brothers) and Sir John Bowring, the British envoy and colonial governor of Hong Kong.

Background

[edit]The Burney Treaty had been signed between the Kingdom of Siam and the British Empire in 1826, coming about as a result of the two powers having a mutual opposition to the Ava Kingdom.[1] That treaty had failed to settle commercial issues, leading to the arrival of Sir John Bowring to Siam in order to negotiate a new one. The treaty negotiated by him allowed free trade by foreign merchants in Bangkok, as all foreign trade had previously been subject to heavy taxation by the Siamese Crown.[2] The treaty also allowed the establishment of a British consulate in Bangkok and guaranteed its full extraterritorial powers, and allowed British subjects to own land in Siam.[1]

Contents

[edit]The regulations in short were:

- British subjects were placed under consular jurisdiction—Britons could not be prosecuted by local Siamese authorities without consent from the British government. Thus, for the first time, Siam granted extraterritoriality to aliens from Great Britain.

- British subjects were given the right to trade freely in all seaports and to reside permanently in Bangkok. They were to be allowed to buy and rent property in the environs of Bangkok; namely, in an area more than four miles from city walls but less than twenty-four hours' journey from the city (calculated from the average speed of Siamese watercraft). British subjects were also to be allowed to travel freely in the interior with passes provided by the consul.

- Measurement duties were abolished and import and export duties were fixed.

- The import duty was fixed at three per cent for all articles, with two exceptions: opium was to be free of duty, but it had to be sold by the opium producer, and bullion was to be free of duty.

- Articles of export were to be taxed just once, whether the tax was called an inland tax, a transit duty, or an export duty.

- British merchants were to be allowed to buy and sell directly with individual Siamese subjects without interference from any third party.

- The Siamese government reserved the right to prohibit the export of salt, rice, and fish whenever these articles were deemed to be scarce in the country.[3]

Effects

[edit]The treaty's largest effect (after liberalising foreign trade) was the legalization of opium exports into Siam, which had previously been banned by the Siamese Crown.[4][5] The treaty was similar in nature to the unequal treaties signed between the Qing government and various Western powers after the First and Second Opium Wars. The Siamese delegation was concerned about Bowring's intentions given the fact that negotiations between Siam and the British Rajah of Sarawak, Sir James Brooke, just five years earlier had ended badly; Brooke had threatened to dispatch his fleet to bombard Siamese ports after negotiations broke down.[6] Despite this, Bowring established an amiable relationship with the Siamese delegation, being welcomed like foreign royalty and showered with pomp (including a 21-gun salute). Though Bowring had become frustrated by the obstinate attitudes of Qing diplomats, he relished the friendly attitude shown by the Siamese, which allowed for the treaty to be negotiated in far smoother terms than other treaties he negotiated.[6][7] The treaty eventually led other Western powers to sign their own bilateral treaties, based on the terms set by the Bowring Treaty.[1] American diplomat Townsend Harris, while on his way to Japan, was delayed in Bangkok for a month by finalization of the Bowring Treaty, but had only to negotiate over a few minor points to convert it into the 1856 Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation with Siam.[8] The Bowring Treaty in particular ensured that the Western powers would not intervene in Siam's internal affairs, and allowed for Siam to remain an independent nation (in contrast to its neighbors).[2] The treaty is now credited by historians with ensuring the economic rejuvenation of Bangkok, as it created a framework in which multilateral trade could operate freely in Southeast Asia, notably between China, Singapore, and Siam.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 7.

- ^ a b c "Ode to Friendship, Celebrating Singapore-Thailand Relations: Introduction". National Archives of Singapore. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Ingram, James C (1971). Economic Change in Thailand 1850-1970. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. pp. 34. ISBN 9780804707824.

- ^ Peter Dale Scott, Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 1 Nov. 2010, Volume 8 | Issue 44 | Number 2, "Operation Paper: The United States and Drugs in Thailand and Burma" 米国とタイ・ビルマの麻薬

- ^ Carl A. Trocki, "Drugs, Taxes, and Chinese Capitalism in Southeast Asia," in Opium Regimes: China, Britain, and Japan, 1839–1952, ed. Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), p. 99

- ^ a b "King Mongkut—the Scholar King at the Crossroad in Thai History". Government of Thailand Public Relations Department. 2004-08-20. Retrieved 2007-04-24.[dead link]

- ^ "Impacts of Trade liberalization under the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) of the World Trade Organization: A Case Study of Rice". Rural Reconstruction and Friends Alumni, Asia Pacific Research Network. 2002-12-01. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "Royal Gifts from Thailand: 1b. Harris Treaty of 1856". National Museum of Natural History. June 21, 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

External links

[edit] The full text of Treaty of friendship and commerce between Great Britain and Siam at Wikisource

The full text of Treaty of friendship and commerce between Great Britain and Siam at Wikisource Media related to Bowring Treaty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bowring Treaty at Wikimedia Commons