Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2009) |

| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

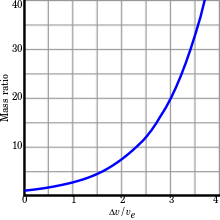

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, or ideal rocket equation, describes the motion of vehicles that follow the basic principle of a rocket: a device that can apply acceleration to itself (a thrust) by expelling part of its mass with high speed and thereby move due to the conservation of momentum. The equation relates the delta-v (the maximum change of velocity of the rocket if no other external forces act) with the effective exhaust velocity and the initial and final mass of a rocket (or other reaction engine).

For any such maneuver (or journey involving a sequence of such maneuvers):

where:

- is delta-v - the maximum change of velocity of the vehicle (with no external forces acting).

- is the initial total mass, including propellant.

- is the final total mass without propellant, also known as dry mass.

- is the effective exhaust velocity.

- refers to the natural logarithm function.

(The equation can also be written using the specific impulse instead of the effective exhaust velocity by applying the formula where is the specific impulse expressed as a time period and is standard gravity ≈ 9.8 m/s2.)

History

The equation is named after Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who independently derived it and published it in his 1903 work.[1] The equation had been derived earlier by the British mathematician William Moore in 1813.[2] The minister William Leitch who was a capable scientist also independently derived the fundamentals of rocketry in 1861.

This equation was independently derived by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky towards the end of the 19th century and is sometimes known under his name, but more often simply referred to as 'the rocket equation' (or sometimes the 'ideal rocket equation').

While the derivation of the rocket equation is a straightforward calculus exercise, Tsiolkovsky is honored as being the first to apply it to the question of whether rockets could achieve speeds necessary for space travel.

Derivation

Consider the following system: File:Var mass system.PNG

In the following derivation, "the rocket" is taken to mean "the rocket and all of its unburned propellant".

Newton's second law of motion relates external forces () to the change in linear momentum of the whole system (including rocket and exhaust) as follows:

where is the momentum of the rocket at time t=0:

and is the momentum of the rocket and exhausted mass at time :

and where, with respect to the observer:

is the velocity of the rocket at time t=0 is the velocity of the rocket at time is the velocity of the mass added to the exhaust (and lost by the rocket) during time is the mass of the rocket at time t=0 is the mass of the rocket at time

The velocity of the exhaust in the observer frame is related to the velocity of the exhaust in the rocket frame by (since exhaust velocity is in the negative direction)

Solving yields:

and, using , since ejecting a positive results in a decrease in mass,

If there are no external forces then (conservation of linear momentum) and

Assuming is constant, this may be integrated to yield:

or equivalently

- or or

where is the initial total mass including propellant, the final total mass, and the velocity of the rocket exhaust with respect to the rocket (the specific impulse, or, if measured in time, that multiplied by gravity-on-Earth acceleration).

The value is the total mass of propellant expended, and hence:

where is the propellant mass fraction (the part of the initial total mass that is spent as working mass).

(delta v) is the integration over time of the magnitude of the acceleration produced by using the rocket engine (what would be the actual acceleration if external forces were absent). In free space, for the case of acceleration in the direction of the velocity, this is the increase of the speed. In the case of an acceleration in opposite direction (deceleration) it is the decrease of the speed. Of course gravity and drag also accelerate the vehicle, and they can add or subtract to the change in velocity experienced by the vehicle. Hence delta-v is not usually the actual change in speed or velocity of the vehicle.

If special relativity is taken into account, the following equation can be derived for a relativistic rocket,[3] with again standing for the rocket's final velocity (after burning off all its fuel and being reduced to a rest mass of ) in the inertial frame of reference where the rocket started at rest (with the rest mass including fuel being initially), and standing for the speed of light in a vacuum:

Writing as , a little algebra allows this equation to be rearranged as

Then, using the identity (here "exp" denotes the exponential function; see also Natural logarithm as well as the "power" identity at Logarithmic identities) and the identity (see Hyperbolic function), this is equivalent to

Other derivations

Impulse-based

The equation can also be derived from the basic integral of acceleration in the form of force (thrust) over mass. By representing the delta-v equation as the following:

where T is thrust, is the initial (wet) mass and is the initial mass minus the final (dry) mass,

and realising that the integral of a resultant force over time is total impulse, assuming thrust is the only force involved,

The integral is found to be:

Realising that impulse over the change in mass is equivalent to force over propellant mass flow rate (p), which is itself equivalent to exhaust velocity,

the integral can be equated to

Acceleration-based

Imagine a rocket at rest in space with no forces exerted on it (Newton's First Law of Motion). However, as soon as its engine is started (clock set to 0) the rocket is expelling gas mass at a constant mass flow rate M (kg/s) and at exhaust velocity relative to the rocket ve (m/s). This creates a constant force propelling the rocket that is equal to M × ve. The mass of fuel the rocket initially has on board is equal to m0 - mf. It will therefore take a time that is equal to (m0 - mf)/M to burn all this fuel. Now, the rocket is subject to a constant force (M × ve), but at the same time its total weight is decreasing steadily because it's expelling gas. According to Newton's Second Law of Motion, this can have only one consequence; its acceleration is increasing steadily. To obtain the acceleration, the propelling force has to be divided by the rocket's total mass. So, the level of acceleration at any moment (t) after ignition and until the fuel runs out is given by;

Since the time it takes to burn the fuel is (m0 - mf)/M the acceleration reaches its maximum of

the moment the last fuel is expelled. Since the exhaust velocity is related to the specific impulse in unit time as

where g0 is the standard gravity, the corresponding maximum g-force is

Since speed is the definite integration of acceleration, and the integration has to start at ignition and end the moment the last propellant leaves the rocket, the following definite integral yields the speed at the moment the fuel runs out;

Terms of the equation

Delta-v

Delta-v (literally "change in velocity"), symbolised as Δv and pronounced delta-vee, as used in spacecraft flight dynamics, is a measure of the impulse that is needed to perform a maneuver such as launch from, or landing on a planet or moon, or in-space orbital maneuver. It is a scalar that has the units of speed. As used in this context, it is not the same as the physical change in velocity of the vehicle.

Delta-v is produced by reaction engines, such as rocket engines and is proportional to the thrust per unit mass, and burn time, and is used to determine the mass of propellant required for the given manoeuvre through the rocket equation.

For multiple manoeuvres, delta-v sums linearly.

For interplanetary missions delta-v is often plotted on a porkchop plot which displays the required mission delta-v as a function of launch date.

Mass fraction

In aerospace engineering, the propellant mass fraction is the portion of a vehicle's mass which does not reach the destination, usually used as a measure of the vehicle's performance. In other words, the propellant mass fraction is the ratio between the propellant mass and the initial mass of the vehicle. In a spacecraft, the destination is usually an orbit, while for aircraft it is their landing location. A higher mass fraction represents less weight in a design. Another related measure is the payload fraction, which is the fraction of initial weight that is payload.

Effective exhaust velocity

The effective exhaust velocity is often specified as a specific impulse and they are related to each other by:

where

- is the specific impulse in seconds,

- is the specific impulse measured in m/s, which is the same as the effective exhaust velocity measured in m/s (or ft/s if g is in ft/s2),

- is the acceleration due to gravity at the Earth's surface, 9.81 m/s2 (in Imperial units 32.2 ft/s2).

Applicability

The rocket equation captures the essentials of rocket flight physics in a single short equation. It also holds true for rocket-like reaction vehicles whenever the effective exhaust velocity is constant, and can be summed or integrated when the effective exhaust velocity varies. The rocket equation only accounts for the reaction force from the rocket engine; it does not include other forces that may act on a rocket, such as aerodynamic or gravitational forces. As such, when using it to calculate the propellant requirement for launch from (or powered descent to) a planet with an atmosphere, the effects of these forces must be included in the delta-V requirement (see Examples below). In what has been called "the tyranny of the rocket equation", there is a limit to the amount of payload that the airship can carry, as higher amounts of propellant increment the overall weight, and thus also increase the fuel consumption.[5] The equation does not apply to non-rocket systems such as aerobraking, gun launches, space elevators, launch loops, or tether propulsion.

The rocket equation can be applied to orbital maneuvers in order to determine how much propellant is needed to change to a particular new orbit, or to find the new orbit as the result of a particular propellant burn. When applying to orbital maneuvers, one assumes an impulsive maneuver, in which the propellant is discharged and delta-v applied instantaneously. This assumption is relatively accurate for short-duration burns such as for mid-course corrections and orbital insertion maneuvers. As the burn duration increases, the result is less accurate due to the effect of gravity on the vehicle over the duration of the maneuver. For low-thrust, long duration propulsion, such as electric propulsion, more complicated analysis based on the propagation of the spacecraft's state vector and the integration of thrust are used to predict orbital motion.

Examples

Assume an exhaust velocity of 4,500 meters per second (15,000 ft/s) and a of 9,700 meters per second (32,000 ft/s) (Earth to LEO, including to overcome gravity and aerodynamic drag).

- Single-stage-to-orbit rocket: = 0.884, therefore 88.4% of the initial total mass has to be propellant. The remaining 11.6% is for the engines, the tank, and the payload. In the case of a space shuttle, it would also include the orbiter.

- Two-stage-to-orbit: suppose that the first stage should provide a of 5,000 meters per second (16,000 ft/s); = 0.671, therefore 67.1% of the initial total mass has to be propellant to the first stage. The remaining mass is 32.9%. After disposing of the first stage, a mass remains equal to this 32.9%, minus the mass of the tank and engines of the first stage. Assume that this is 8% of the initial total mass, then 24.9% remains. The second stage should provide a of 4,700 meters per second (15,000 ft/s); = 0.648, therefore 64.8% of the remaining mass has to be propellant, which is 16.2%, and 8.7% remains for the tank and engines of the second stage, the payload, and in the case of a space shuttle, also the orbiter. Thus together 16.7% is available for all engines, the tanks, the payload, and the possible orbiter.

Stages

In the case of sequentially thrusting rocket stages, the equation applies for each stage, where for each stage the initial mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket after discarding the previous stage, and the final mass in the equation is the total mass of the rocket just before discarding the stage concerned. For each stage the specific impulse may be different.

For example, if 80% of the mass of a rocket is the fuel of the first stage, and 10% is the dry mass of the first stage, and 10% is the remaining rocket, then

With three similar, subsequently smaller stages with the same for each stage, we have

and the payload is 10%*10%*10% = 0.1% of the initial mass.

A comparable SSTO rocket, also with a 0.1% payload, could have a mass of 11.1% for fuel tanks and engines, and 88.8% for fuel. This would give

If the motor of a new stage is ignited before the previous stage has been discarded and the simultaneously working motors have a different specific impulse (as is often the case with solid rocket boosters and a liquid-fuel stage), the situation is more complicated.

Common misconceptions

When viewed as a variable-mass system, a rocket cannot be directly analyzed with Newton's second law of motion because the law is valid for constant-mass systems only.[6][7][8] It can cause confusion that the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation looks similar to the relativistic force equation . Using this formula with as the varying mass of the rocket seems to derive Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, but this derivation is not correct. Notice that the effective exhaust velocity doesn't even appear in this formula.

See also

- Delta-v budget

- Oberth effect applying delta-v in a gravity well increases the final velocity

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Mass ratio

- Working mass

- Relativistic rocket

- Reversibility of orbits

- Variable-mass systems

References

- ^ К. Ціолковскій, Изслѣдованіе мировыхъ пространствъ реактивными приборами, 1903 (available online here in a RARed PDF)

- ^ Moore, William; of the Military Academy at Woolwich (1813). A Treatise on the Motion of Rockets. To which is added, An Essay on Naval Gunnery. London: G. and S. Robinson.

- ^ Forward, Robert L. "A Transparent Derivation of the Relativistic Rocket Equation" (see the right side of equation 15 on the last page, with R as the ratio of initial to final mass and w as the exhaust velocity, corresponding to ve in the notation of this article)

- ^ Benson, Tom (2008-07-11). "Specific impulse". NASA. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ "NASA - The Tyranny of the Rocket Equation". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ^ Plastino, Angel R.; Muzzio, Juan C. (1992). "On the use and abuse of Newton's second law for variable mass problems". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 53 (3). Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers: 227–232. Bibcode:1992CeMDA..53..227P. doi:10.1007/BF00052611. ISSN 0923-2958. "We may conclude emphasizing that Newton's second law is valid for constant mass only. When the mass varies due to accretion or ablation, [an alternate equation explicitly accounting for the changing mass] should be used."

- ^ Halliday; Resnick. Physics. Vol. 1. p. 199. ISBN 0-471-03710-9.

It is important to note that we cannot derive a general expression for Newton's second law for variable mass systems by treating the mass in F = dP/dt = d(Mv) as a variable. [...] We can use F = dP/dt to analyze variable mass systems only if we apply it to an entire system of constant mass having parts among which there is an interchange of mass.

[Emphasis as in the original] - ^

Kleppner, Daniel; Robert Kolenkow (1973). An Introduction to Mechanics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-07-035048-5.

Recall that F = dP/dt was established for a system composed of a certain set of particles[. ... I]t is essential to deal with the same set of particles throughout the time interval[. ...] Consequently, the mass of the system can not change during the time of interest.

![{\displaystyle {\frac {m_{0}}{m_{1}}}=\left[{\frac {1+{\frac {\Delta v}{c}}}{1-{\frac {\Delta v}{c}}}}\right]^{\frac {c}{2v_{e}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c80b17588a3cf48740fdf5e53bb7d9a6d38ebf9d)

![{\displaystyle R^{\frac {2v_{e}}{c}}=\exp \left[{\frac {2v_{e}}{c}}\ln R\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a7466886986a08129e115343fbab4b9d624056dc)