Tuatara

| Tuatara | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male tuatara | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Sphenodon Gray, 1831

|

| Species | |

|

Sphenodon punctatus (Gray, 1842) | |

| |

| dark red: range (North Island, New Zealand) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Hatteria punctata, Gray 1842 | |

The tuatara is an amniote of the family Sphenodontidae, endemic to New Zealand. The two species of tuatara are the only surviving members of the Sphenodontians who flourished around 200 million years ago,[1] and are in the genus Sphenodon. Tuatara resemble lizards, but are equally related to lizards and snakes, both of which are classified as Squamata, the closest living relatives of tuatara. For this reason, tuatara are of great interest in the study of the evolution of lizards and snakes, and for the reconstruction of the appearance and habits of the earliest diapsids (the group that additionally includes birds and crocodiles).

Tuatara are greenish brown, and measure up to 80 cm from head to tail-tip[2] with a spiny crest along the back, especially pronounced in males. Their dentition, in which two rows of teeth in the upper jaw overlap one row on the lower jaw, is unique among living species. They are further unusual in having a pronounced parietal eye, dubbed the "third eye", whose current function is a subject of ongoing research. They are able to hear although no external ear is present, and have a number of unique features in their skeleton, some of them apparently evolutionarily retained from fish.

The tuatara has been classified as an endangered species since 1895[3][4] (the second species, S. guntheri, was not known until 1989).[2] Tuatara, like many of New Zealand's native animals, are threatened by habitat loss and the introduced Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans). They were extinct on the mainland, with the remaining populations confined to 32 offshore islands,[5] until the first mainland release into the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Wildlife Sanctuary in 2005.[6]

The name "tuatara" derives from the Māori language, and means "peaks on the back".[7]

Taxonomy and evolution

Tuatara, and their sister group Squamata (which includes lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians), belong to the superorder Lepidosauria, the only surviving taxon within Lepidosauromorpha. Squamates and tuatara both show caudal autotomy (loss of the tail-tip when threatened), and have a transverse cloacal slit.[8] The origin of the tuatara probably lies close to the split between the Lepidosauromorpha and the Archosauromorpha. Though tuatara resemble lizards, the similarity is mostly superficial, since the family has several characteristics unique among reptiles. The typical lizard shape is very common for the early amniotes; the oldest known fossil of a reptile, the Hylonomus, resembles a modern lizard.[9]

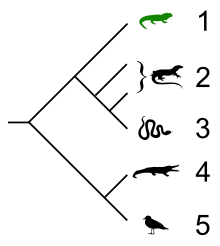

1. Tuatara

2. Lizards

3. Snakes

4. Crocodiles

5. Birds

"Lizards" are polyphyletic. Branch lengths do not indicate divergence times.

Tuatara were originally classified as lizards in 1831 when the British Museum received a skull.[11] The genus remained misclassified until 1867, when Albert Günther of the British Museum noted features similar to birds, turtles and crocodiles. He proposed the order Rhynchocephalia (meaning "beak head") for the tuatara and its fossil relatives.[12] Now, most authors prefer to use the more exclusive order name of Sphenodontia for the tuatara and its closest living relatives.[13]

During the years since the description of the Rhynchocephalia, many disparately related species have been added to this order. This has resulted in turning the Rhynchocephalia into what taxonomists call a "wastebasket taxon".[14] In 1925, Williston proposed the Sphenodontia to include only tuatara and their closest fossil relatives.[14] Sphenodon is derived from the Greek for "wedge" (sphenos) and "tooth" (odon(t)).[15]

Tuatara have been referred to as living fossils.[16] This means that they have remained mostly unchanged throughout their entire history, which is approximately 220 million years.[17] However, taxonomic work[18] on Sphenodontia has shown that this group has undergone a variety of changes throughout the Mesozoic. Many of the niches associated with lizards today were then held by sphenodontians. There was even a successful group of aquatic sphenodontians known as pleurosaurs, which differed markedly from living tuatara. Tuatara show cold weather adaptations that allow them to thrive on the islands of New Zealand; these adaptations may be unique to tuatara since their sphenodontian ancestors lived in the much warmer climates of the Mesozoic.

There are two extant species of tuatara: Sphenodon punctatus and the much rarer Sphenodon guntheri, or Brothers Island tuatara, which is confined to North Brother Island in Cook Strait.[19] The species name punctatus is Latin for "spotted",[20] and guntheri refers to Albert Günther. S. punctatus was named when only one species was known, and its name is misleading, since both species can have spots. The Brother's Island tuatara (S. guntheri) has olive brown skin with yellowish patches, while the colour of the other species, (S. punctatus), ranges from olive green through grey to dark pink or brick red, often mottled, and always with white spots.[6][8][21] In addition, S. guntheri is considerably smaller.[22]

Sphenodon punctatus is further divided into two subspecies: the Cook Strait tuatara (unnamed subspecies), which lives on other islands in and near Cook Strait, and the northern tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus punctatus), which lives on the Bay of Plenty, and some islands further north.[5]

A third, extinct species of Sphenodon was identified in November of 1885 by William Colenso, who was sent an incomplete sub-fossil specimen from a local coal mine. Colenso named the new species S. diversum.[23]

Description

The tuatara is considered the most unspecialised living amniote; the brain and mode of locomotion resemble that of amphibians and the heart is more primitive than any other reptile.[17]

Both species are sexually dimorphic, males being larger.[8] Adult S. punctatus males measure 61 centimetres (24 in) in length and females 45 centimetres (18 in).[8] The San Diego Zoo even cites a length of up to 80 cm (31 in).[24] Males weigh up to 1 kilogram (2.2 lb), and females up to 0.5 kilograms (1.1 lb).[8] Brother's Island tuatara are slightly smaller, weighing up to 660g.[22]

The tuatara's greenish brown colour matches its environment, and can change over its lifetime, since tuatara shed their skin at least once per year as adults,[21] and three or four times a year as juveniles. Tuatara sexes differ in more than size. The spiny crest on a tuatara's back, made of triangular soft folds of skin, is bigger in males than in females, and can be stiffened for display. The male abdomen is narrower than the female's.[25]

Skull

In the course of evolution, the skull has been modified in most diapsids from the original version evident in the fossil record. However, in the tuatara, all the original features are preserved: it has two openings (temporal fenestra) on each side of the skull, with complete arches. In addition, in the tuatara, the upper jaw is firmly attached to the skull.[8] This makes for a very rigid, inflexible construction. Testudines (turtle and tortoise) skulls with their single temporal fenestrum are widely considered to be the most primitive among amniotes, though some research suggests they might have lost the temporal holes rather than never having had them.[8][26][27]

The tip of the upper jaw is beak-like and separated from the remainder of the jaw by a notch. There is a single row of teeth in the lower jaw and a double row in the upper jaw, with the bottom row fitting perfectly between the two upper rows when the mouth is closed.[8] This is a tooth arrangement not seen in any other reptiles; although most snakes also have a double row of teeth in their upper jaw, their arrangement and function is different from the tuatara's. The jaws, joined by ligament, chew with backwards and forwards movements combined with a shearing up and down action. The force of the bite is suitable for shearing chitin and bone.[8] The tuatara's teeth are not replaced, since they are not separate structures like real teeth, but sharp projections of the jaw bone.[28] As their teeth wear down, older tuatara have to switch to softer prey such as earthworms, larvae, and slugs, and eventually have to chew their food between smooth jaw bones.[29]

Sensory organs

In tuatara, both eyes can focus independently, and are specialized with a "duplex retina" that contains two types of visual cells for vision by both day and night, and a tapetum lucidum which reflects on to the retina to enhance vision at night. There is also a third eyelid on each eye, the nictitating membrane.

The tuatara has a third eye on the top of its head called the parietal eye. It has its own lens, cornea, retina with rod-like structures and degenerated nerve connection to the brain, suggesting it evolved from a real eye. The parietal eye is only visible in hatchlings, which have a translucent patch at the top centre of the skull. After four to six months it becomes covered with opaque scales and pigment.[8] Its purpose is unknown, but it may be useful in absorbing ultraviolet rays to manufacture vitamin D,[7] as well as to determine light/dark cycles, and help with thermoregulation.[8] Of all extant tetrapods, the parietal eye is most pronounced in the tuatara. The parietal eye is part of the pineal complex, another part of which is the pineal gland, which in tuatara secretes melatonin at night.[8] It has been shown that some salamanders use their pineal body to perceive polarised light, and thus determine the position of the sun, even under cloud cover, aiding navigation.[30]

Together with turtles, the tuatara has the most primitive hearing organs among the amniotes. There is no eardrum and no earhole,[28] and the middle ear cavity is filled with loose tissue, mostly adipose tissue. The stapes comes into contact with the quadrate (which is immovable) as well as the hyoid and squamosal. The hair cells are unspecialized, innervated by both afferent and efferent nerve fibres, and respond only to low frequencies. Even though the hearing organs are poorly developed and primitive with no visible external ears, they can still show a frequency response from 100-800 Hz, with peak sensitivity of 40 dB at 200 Hz.[31]

Spine and ribs

The tuatara spine is made up of hour-glass shaped amphicoelous vertebrae, concave both before and behind.[28] This is the usual condition of fish vertebrae and some amphibians, but is unique to tuatara within the amniotes.

The tuatara has gastralia, rib-like bones also called gastric or abdominal ribs,[32] the presumed ancestral trait of diapsids. They are found in some lizards (in lizards they are mostly made of cartilage), crocodiles and the tuatara, and are not attached to the spine or thoracic ribs.

The real ribs are small projections, with small, hooked bones, called uncinate processes, found on the rear of each rib.[28] This feature is also present in birds. The tuatara is the only living tetrapod with well developed gastralia and uncinate processes.

In the early tetrapods, the gastralia and ribs with uncinate processes, together with bony elements such as bony plates in the skin (osteoderms) and clavicles (collar bone), would have formed a sort of exo-skeleton around the body, protecting the belly and helped to hold in the guts and inner organs. These anatomical details most likely evolved from structures involved in locomotion even before the vertebrates migrated onto land. It is also possible the gastralia were involved in the breathing process in primitive and extinct amphibians and reptiles. The pelvis and shoulder girdles are arranged differently than in lizards, as is the case with other parts of the internal anatomy and its scales.[33]

Behaviour

Adult tuatara are terrestrial and nocturnal reptiles, though they will often bask in the sun to warm their bodies. Hatchlings hide under logs and stones, and are diurnal, likely because adults are cannibalistic. Tuatara thrive in temperatures much lower than those tolerated by most reptiles, and hibernate during winter.[34] They can maintain normal activities at temperatures as low as 7° C, while temperatures over 28°C are generally fatal. The optimal body temperature for the tuatara is from 16 to 21°C, the lowest of any reptile.[35] The body temperature of tuatara is lower than that of other reptiles ranging from 5.2–11.2°C over a day, whereas most reptiles have body temperatures around 20°C.[36] The low body temperature results in a slower metabolism.

Burrowing seabirds such as petrels, prions and shearwaters share the tuatara's island habitat during the bird's nesting season. The tuatara use the bird's burrows for shelter when available, or dig their own. The seabirds' guano helps to maintain invertebrate populations that tuatara predominantly prey on; including beetles, crickets and spiders. Their diet also consists of frogs, lizards and bird's eggs and chicks. The eggs and young of seabirds that are seasonally available as food for tuatara may provide beneficial fatty acids.[8] Tuatara will bite when approached, and do not let go easily.[37] They can, however, be easily caught by lowering a tennis ball attached to a length of plastic into their burrow, and slowly retrieving the ball with the tuatara attached.[37]

Tuatara reproduce very slowly, taking ten years to reach sexual maturity. Mating occurs in midsummer; females mate and lay eggs once every four years.[38] During courtship, a male makes his skin darker, raises his crests and parades toward the female. He slowly walks in circles around the female with stiffened legs. The female will either submit, and allow the male to mount her, or retreat to her burrow. [39] Males do not have a penis; they reproduce by the male lifting the tail of the female and placing his vent over hers. The sperm is then transferred into the female, much like the mating process in birds.[40]

Tuatara eggs have a soft, parchment-like shell. It takes the females between one and three years to provide eggs with yolk, and up to seven months to form the shell. It then takes between 12 and 15 months from copulation to hatching. This means reproduction occurs at 2 to 5 year intervals, the slowest in any reptile.[8] The sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature of the egg, with warmer eggs tending to produce male tuatara, and cooler eggs producing females. Eggs incubated at 21°C have an equal chance of being male or female. However, at 22°C, 80% are likely to be males, and at 20°C, 80% are likely to be females; at 18°C all hatchlings will be females.[7] There is some evidence that sex determination in tuatara is determined by both genetic and environmental factors.[41]

Tuatara probably have the slowest growth rates of any reptile,[8] continuing to grow larger for the first 35 years of their lives.[7] The average lifespan is about 60 years, but they can live to be over 100 years old.[7]

Conservation

Distribution and threats

Tuatara were long confined to 32 offshore islands free of mammals.[5] The islands are difficult to get to,[45] and are colonised by few animal species, indicating that some animals absent from these islands may have caused tuatara to disappear from the mainland. However, kiore (Polynesian rats) had recently established on several of the islands, and tuatara were persisting, but not breeding, on these islands.[46][47] Additionally, tuatara were much rarer on the rat-inhabited islands.[47]

Introductions

Brothers Island tuatara

Sphenodon guntheri is present naturally on one small island with a population of approximately 400. In 1995, 50 juvenile and 18 adult Brothers Island tuatara were moved to Titi Island in Cook Strait, and their establishment monitored. Two years later, more than half of the animals had been re-sighted and all but one had gained weight. In 1998, 34 juveniles from captive breeding and 20 wild caught adults were similarly transferred to Matiu Island, a more publicly accessible location. The captive juveniles were from induced layings from wild females.[43]

In late October 2007, it was announced that 50 tuatara collected as eggs from North Brother Island and hatched at Victoria University were being released onto Long Island in Cook Strait. The animals had been cared for at Wellington Zoo for the last five years and have been kept in secret in a specially built enclosure at the zoo, off display.[48]

Northern tuatara

Sphenodon punctatus naturally occurs on 29 islands and its population is estimated to be over 60,000 individuals.[8]

In 1996, 32 adult northern tuatara were moved from Moutoki Island to Moutohora. The carrying capacity of Moutohora is estimated at 8500 individuals, and the island could allow public viewing of wild tuatara.[43]

A mainland release of S. punctatus occurred in 2005 in the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Wildlife Sanctuary.[6] The second mainland release took place in October 2007, when a further 130 were transferred from Stephens Island to the Karori Sanctuary.[49]

Eradication of rats

In 1990 and 1991, tuatara were removed from Stanley, Red Mercury and Cuvier Islands, and maintained in captivity to allow Pacific rats to be eradicated on those islands. All three populations bred in captivity, and after successful eradication, all individuals including the new juveniles were returned to their islands of origin. In the 1991/92 season, Little Barrier Island was found to hold only eight tuatara, which were taken into in situ captivity, where females produced 42 eggs, which were incubated at Victoria University. The resulting offspring were subsequently held in an enclosure on the island. The 2001-2011 Recovery Plan, published in 2001, states that eradication of rats from this island is pending.[43]

Pacific rats were, however, eradicated on Middle Chain Island in 1992, Whatupuke in 1993, Lady Alice Island in 1994, and Coppermine Island in 1997. Following this program, juveniles have once again been seen on the latter three islands. In contrast, rats persist on Hen Island of the same group, and no juvenile tuatara had been seen there as of 2001. Middle Chain Island holds no tuatara, but it is considered possible for rats to swim between Middle Chain and other islands that do hold tuatara, and the rats were eradicated to prevent this.[43]

Another rodent eradication was carried out on the Rangitoto Islands east of D’Urville Island, to prepare for the release of 432 Cook Strait tuatara juveniles in 2004, which were being raised at Victoria University as of 2001.[43]

Captive breeding

There are several Tuatara breeding programmes within New Zealand. Southland Museum and Art Gallery in Invercargill, was the first to have a tuatara breeding programme; they breed Sphenodon punctatus. Hamilton Zoo and Wellington Zoo also breed tuatara for release into the wild. The Victoria University of Wellington maintains a research programme into the captive breeding of tuatara, and the Pukaha Mount Bruce Wildlife Centre keeps a pair and juvenile. The WildNZ Trust has a tuatara breeding enclosure at Ruawai.

Cultural significance

Tuatara feature in a number of indigenous legends, and are held as ariki (God forms). Tuatara are regarded as the messengers of Whiro, the god of death and disaster, and Māori women are forbidden to eat them.[50] Tuatara also indicate tapu (the borders of what is sacred and restricted),[51] beyond which there is mana, meaning there could be serious consequences if that boundary is crossed.[51] Māori women would sometimes tattoo images of lizards, some of which may represent tuatara, near their genitals.[51] Today, tuatara are regarded as a taonga (special treasure).[52]

The tuatara was featured on one side of the New Zealand 5 cent coin, which was phased out in October 2006. Tuatara was also the name of the Journal of the Biological Society of Victoria University College and subsequently Victoria University of Wellington, published from 1947 until 1993.[53]

References

- ^ Burnie, David (2001). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. New York, New York: DK Publishing, Inc. p. 375. ISBN 0-7894-7764-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Reptiles:Tuatara". Animal Bytes. Zoological Society of San Diego. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Newman 1987.

- ^ Cree, Allison (1993). "Tuatara Recovery Plan" (PDF). Threatened Species Recovery Plan Series No.9. Threatened Species Unit, Department of Conservation, Government of New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) ISBN 0478014627 - ^ a b c "Facts about tuatara". Conservation: Native Species. Threatened Species Unit, Department of Conservation, Government of New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- ^ a b c "Tuatara Factsheet (Sphenodon punctatus)". Sanctuary Wildlife. Karori Sanctuary Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ a b c d e "The Tuatara". Kiwi Conservation Club: Fact Sheets. Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Cree, Alison. 2002. Tuatara. In: Halliday, Tim and Adler, Kraig (eds.), The new encyclopedia of reptiles and amphibians, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 210-211. ISBN 0-19-852507-9

- ^ "Hylonomus lyelli". Symbols. Province of Nova Scotia. May, 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Fry B.G., Vidal N., Norman J.A., Vonk F.J., Scheib H., Ramjan R., Kuruppu S., Fung K., Hedges S.B., Richardson M.K., Hodgson W.C., Ignjatovic V., Summerhayes R. and Kochva E. (2005) "Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes." Nature doi:10.1038/nature04328 (online 17 November 2005).

- ^ Lutz 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Lutz 2005, p. 43.

- ^ "Lepidosauromorpha: Lizards, snakes, Sphenodon, and their extinct relatives". The Tree of Life Web Project. Tree of Life Web Project. 1995. Retrieved 2006-07-27.

- ^ a b Fraser, Nicholas; Sues, Hans-Dieter; (eds) (1994). "Phylogeny" In the Shadow of the Dinosaurs: Early Mesozoic Tetrapods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45242-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""Sphenodon"". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ "Tuatara". New Zealand Ecology: Living Fossils. TerraNature Trust. 2004. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ^ a b Russell, Matt (August, 1998). "Tuatara, Relics of a Lost Age". Cold Blooded News. Colorado Herpetological Society. Retrieved 2006-05-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wu, Xiao-Chun (1994). "Late Triassic-Early Jurassic sphenodontians from China and the phylogeny of the Sphenodontia" in Nicholas Fraser & Hans-Dieter Sues (eds) In the Shadow of the Dinosaurs: Early Mesozoic Tetrapods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45242-2.

- ^ "Tuatara - Sphenodon punctatus". Science and Nature: Animals. bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2006-02-28.

- ^ Stearn, William T (April 1, 2004). Botanical Latin. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press Inc. pp. p. 476. ISBN 0881926272.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Lutz 2005, p. 16.

- ^ a b Gill, Brian & Whitaker, Tony. 1996. New Zealand Frogs and reptiles. David Bateman publishing, pp. 22-24. ISBN 1869532643

- ^ Colenso, W. (1885). "Notes on the Bones of a Species of Sphenodon, (S. diversum, Col.,) apparently distinct from the Species already known" (PDF). Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 18: 118–128.

- ^ http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-tuatara.html

- ^ "Tuataras at Animal Corner". Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Rieppel, O., and DeBraga, M. (1996). "Turtles as diapsid reptiles." Nature, 384: 453-455.

- ^ Zardoya, R., and Meyer, A. (1998). "Complete mitochondrial genome suggests diapsid affinities of turtles." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(24): 14226-14231.

- ^ a b c d Lutz 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Mlot, Christine (1997-11-08). "Return of the Tuatara:A relic from the age of dinosaurs gets a human assist" (PDF). Science News. Science News. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ^ Halliday, Tim R. 2002. Salamanders and newts: Finding breeding ponds. In: Halliday, Tim and Adler, Kraig (eds.), The new encyclopedia of reptiles and amphibians, Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 52. ISBN 0-19-852507-9

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa (2003-09-06). "Reptile Hearing". Melissa Kaplan's Herp Care Collection. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Zoo Berlin: Tuatara". Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ "Tuatara Reptile, New Zealand". Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Tuatara: Facts". Southland Museum. January 18, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ Musico, Bruce (1999). "Sphenodon punctatus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

- ^ Thompson MB and Daugherty CH (1998). "Metabolism of tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus". Comparative biochemistry and physiology A. 119: 519–522. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(97)00459-5.

- ^ a b Lutz 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Cree; et al. (1992). "Reproductive cycles of male and female tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) on Stephens Island, New Zealand". Journal of Zoology. 226: 199–217.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ C. Gand, J.C. Gillingham and D.L. Clark (1984). "Courtship, mating and male combat in Tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus". Journal of Herpetology. 18(2): 194–197. doi:10.2307/1563749.

- ^ Lutz 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Cree, A., Thompson, M. B. & Daugherty, C. H. 1995. Tuatara sex determination. Nature 375, 543. doi:10.1038/375543a0

- ^ Daugherty, C. H., A. Cree, J. M. Hay & M. B. Thompson. 1990. Neglected taxonomy and continuing extinctions of tuatara (Sphenodon). Nature 347, 177-179. doi:10.1038/347177a0

- ^ a b c d e f Gaze, Peter (2001). "Tuatara recovery plan 2001-2011" (PDF). Threatened Species Recovery Plan 47. Biodiversity Recovery Unit, Department of Conservation, Government of New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-06-02. ISBN 0478221312

- ^ Beston, Anne (2003-10-25). "New Zealand Herald: Tuatara Release" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lutz 2005, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Crook, I. G. 1973. The tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus Gray, on islands with and without populations of the Polynesian rat, Rattus exulans (Peale). Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society 20:115-120.

- ^ a b Cree, A., Daugherty, C.H. and Hay, J.M. 1995. Reproduction of a rare New Zealand reptile, the tuatara Sphenodon punctatus,on rat-free and rat-inhabited islands. Conservation Biology 9, 373-383.doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.9020373.x

- ^ "Rare tuatara raised at Wellington Zoo". 29 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "130 tuatara find sanctuary". The Dominion Post. 20 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) (Archive at webcitation.org) - ^ Williams, David (2001). "Chapter 6: Traditional Kaitiakitanga Rights and Responsibilities" (PDF). Wai 262 Report: Matauranga Maori and Taonga. Waitangi Tribunal. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- ^ a b c Kristina M. Ramstad, N. J. Nelson, G. Paine, D. Beech, A. Paul, P. Paul, F. W. Allendorf, C. H. Daugherty (2007) Species and Cultural Conservation in New Zealand: Maori Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Tuatara. Conservation Biology 21 (2), 455–464. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00620.x

- ^ Lutz 2005, p. 64.

- ^ http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-corpus-tuatara.html

Bibliography

- Template:Harvard reference

- McKintyre, Mary (1997). Conservation of the Tuatara. Victoria University Press. ISBN 0-86473-303-8.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Parkinson, Brian (2000). The Tuatara. Reed Children’s Books. ISBN 1-86948-831-8.

External links

- "Tuatara captive management plan and husbandry manual" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

{{cite web}}: Text "2000" ignored (help); Text "B. Blanchard et. al." ignored (help) - "Digimorph - Sphenodon punctatus (tuatara) - 3D visualisations from X-ray CT scans". Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- "ARKive - images and movies of the Brothers Island tuatara (Sphenodon guntheri)". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- "Evolution of a third eye in some animals? MadSci Network". Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- "The Lonely Eye". Retrieved 2006-10-11.

Institutions that keep tuatara

New Zealand

- Auckland Zoo

- Hamilton Zoo Tuatara breeding

- Natureland Zoo, Nelson, NZ

- Pukaha Mount Bruce

- Kiwi Birdlife Park Queenstown

- Southland Museum and Art Gallery

- Victoria University of Wellington

- Wellington Zoo

- WildNZ Trust Projects at Ruawai

Australia

Europe

United States

- Dallas Zoo

- Saint Louis Zoo

- San Diego Zoo (S. guntheri)

- Toledo Zoo