User:Matthew12263/Umber

Umber is a natural earth pigment created by mixing iron oxide, manganese oxide, and hydroxides to make a brownish color that can be combined to vary between shades of yellow, red, and green.[2] Umber is considered one of the oldest pigments known to humans, first seen in Ajanta Caves in 200 BC-600 AD.[3]: 378 Umber's advantages are its highly versatile color, warm tone, and quick drying abilities.[4]: 137–139 While it is thought that Umber's name comes from its geographic origin in Umbria, critics believe that it derives from the Latin word umbra, which means "shadow."[5]: 250 The belief that its name derives from the word for shadow is fitting, as the color helps create shadows.[5]: 250 In addition, the color is primarily imported from Turkey, specifically Cyprus, and not Italy.[5]: 250 Umber is typically mined from open pits or underground mines and ground into a fine powder washed to remove impurities.[2] In the 20th century, the rise of synthetic dyes decreased the demand for natural pigments such as Umber.[6]

History[edit]

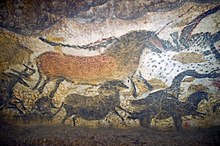

Umber was first identified between 200 BC and 600 AD during the neolithic period in Ajanta Caves found in Buddhist caves in India.[3] Ocher, a family of earth pigments which includes Umber, was later rediscovered in 1940 in the caves of Altamira throughout Spain and the Lascaux Cave in France.[5]: 251 Throughout the Medieval ages, dark brown pigments such as Umber were rarely seen in art, with a preference for bright and vivid colors.[7]: 166 Umber was, however, used in Medieval art, where it was mixed with pigments to create different shades of brown, most often seen for skin tones.[8] Umber gained use in Europe in the late 15th century.[7]: 168 Umber became more popular during the Renaissance when its versatility, earthy appearance, availability, and inexpensiveness were recognized.[5]: 251

Umber gained widespread popularity in Dutch landscape painting in the eighth century.[3]: 378 Artists recognized the value of Umber’s high stability, inertness, and drying abilities.[4]: 137–139 It became a standard color within eighteenth-century palettes throughout Europe.[3]: 378 Umber’s popularity grew during the Baroque period with the rise of the chiaroscuro style.[6] Umber allowed painters to create an intense light and dark contrast.[6] Underpainting was another popular technique for painting that used Umber as a base color.[9] Umber was valuable in deploying this technique, creating a range of earth like tones with various layering of color.[6]

Toward the end of the 19th century, the Impressionist Movement started to use cheaper and more readily available synthetic dyes and reject natural pigments like Umber to create mixed hues of brown.[6] The impressionists chose to make their own browns from mixtures of red, yellow, green, blue and other pigments, particularly the new synthetic pigments such as cobalt blue and emerald green that had just been introduced.[10] In the 20th century, natural umber pigments began to be replaced by pigments made with synthetic iron oxide and manganese oxide. [6]

Criticism[edit]

Beginning in the 17th century, Umber was increasingly criticized within the art community. British painter Edward Norgate, prominent with British royalty and aristocracy, called Umber "a foul and greasy color."[11]: 56 In the 18th century, Spanish painter Antonio Palomino called Umber "very false."[11]: 56 Jan Blockx, a Belgian painter, opined, "umber should not appear on the palette of the conscientious painter."[11]: 56

Visual properties[edit]

Umber is a natural brown pigment extracted from clay containing iron, manganese, and hydroxides.[12] Umber has diverse hues, ranging from yellow-brown to reddish-brown and even green-brown.[6] The color shade varies depending on the proportions of the components.[6] When heated, Umber becomes a more intense color and can look almost black.[6] Burnt Umber is produced by calcining the raw version.[6] The raw form of Umber is typically used for ceramics because it is less expensive.[13]

These warm and earthy tones make it a valuable and versatile pigment for oil painting and other artwork.[13] Umber's high opacity and reactivity of light allow the pigment to have strong hiding power.[14] It is insoluble in water, resistant to alkalis and weak acids, and non-reactive with cement, solvents, oils, and most resins.[13]

Permanence[edit]

Umber is considered one of the world's most permanent pigments due to its rarity of fading.[4]: 139 When Umber is mixed with other colors, its stability increases the pigment's permanence.[4]: 138 As Umber has a natural pigmentation, it can darken over time.[15] However, Umber can simultaneously absorb oil from paint, making the color more brittle and susceptible to cracking.[16]

Notable occurrences[edit]

Umber became widely used throughout the Renaissance period for oil paintings.[6] In his painting, the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci used Umber for the brown tones throughout his subject’s hair and clothing.[17] Da Vinci also extensively used Umber in his painting the Last Supper to create shadows and outlines of the figures.[18] Throughout the Baroque period, many renowned painters used Umber.[6] Rembrandt used Umber in his darkly atmospheric painting The Night Watch, where he used Umber to give depth and a shadowy quality to the militia in the background, setting off the sunlight drenching the three main figures.[19]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Lesso, Rosie (2020-05-12). "The Mysterious Shadows of Umber - the thread". Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ a b "Pigments through the Ages - Overview - Umber". www.webexhibits.org. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ a b c d Eastaugh, Nicholas; Walsh, Valentine; Chaplin, Tracey; Siddall, Ruth (2007-03-30). "Pigment Compendium: A Dictionary of Historical Pigments". doi:10.4324/9780080473765.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d Roy, Ashok; Harley, R. D. (1984-01-01). "Artists' Pigments c. 1600-1835: A Study in English Documentary Sources". Studies in Conservation. 29 (1): 54. doi:10.2307/1505948. ISSN 0039-3630.

- ^ a b c d e Brill, Michael H. (2017-10-24). "The Secret Lives of Color". Color Research & Application. 45 (3): 567–568. doi:10.1002/col.22496. ISSN 0361-2317.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Versatility and Sustainability of Umber: Exploring the Natural Brown Earth Pigment". www.naturalpigments.com. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ a b Gettens, Rutherford J. (1966). Painting materials : a short encyclopaedia. George L. Stout. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21597-0. OCLC 518445.

- ^ "Medieval manuscripts blog: Science". blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "Underpainting advice". John Pototschnik Fine Art. 2020-02-02. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The secret lives of colour. London. ISBN 978-1-4736-3081-9. OCLC 936144129.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Artists' pigments : a handbook of their history and characteristics. Robert L. Feller, Ashok Roy, Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Barbara Hepburn Berrie. Washington: National Gallery of Art. 1750-01-01. ISBN 0-89468-086-2. OCLC 12804059.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Shorter Oxford English dictionary on historical principles. William R. Trumble, Angus Stevenson, Lesley Brown (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 0-19-860575-7. OCLC 50017616.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c "Raw Umber".

- ^ "Umber - CAMEO". cameo.mfa.org. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "Do Oil Paintings Darken Over Time? | Sustain The Art". sustaintheart.com. 2022-06-27. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "Brown Pigments". Traditional Oil Painting. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ a b Foundation, Mona Lisa (2012-09-08). "Analysis of the Materials used in the 'Earlier Mona Lisa'". The Mona Lisa Foundation. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "What is actually depicted on The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci?". Arthive. 2017-04-12. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Burke, Danielle (2022-10-13). "Restoring a bitumen damaged copy of The Night Watch". Fine Art Restoration Company. Retrieved 2023-04-15.