User:Medwa823/sandbox

Muriel Rukeyser (December 15, 1913 – February 12, 1980) was an American poet and political activist, best known for her poems about equality, feminism, social justice, and Judaism. Kenneth Rexroth said that she was the greatest poet of her "exact generation."[1]

One of her most powerful pieces was a group of poems titled The Book of the Dead (1938), documenting the details of the Hawk's Nest incident, an industrial disaster in which hundreds of miners died of silicosis.

Her poem "To be a Jew in the Twentieth Century" (1944), on the theme of Judaism as a gift, was adopted by the American Reform and Reconstructionist movements for their prayer books, something Rukeyser said "astonished" her, as she had remained distant from Judaism throughout her early life.[2]

Early life[edit]

Muriel Rukeyser was born on December 15, 1913 to Lawrence and Myra Lyons Rukeyser.[3] Her parents were American-born and she was raised as a secular Jew; her family, despite living in New York City, did not have any cultural connections with the Jewish community.[4] During her later childhood "her mother experienced a return to religion" and Rukeyser would go on to attend a Reform synagogue and Hebrew School for seven years.[5] She attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, a private school in The Bronx[6], then Vassar College in Poughkeepsie.[7] From 1930 to 32, she attended Columbia University, but had to end her studies when her father went bankrupt.[8]

Her literary career began in 1935 when her book of poetry Theory of Flight, based on flying lessons she took, was chosen by the American poet Stephen Vincent Benét for publication in the Yale Younger Poets Series.

Activism and writing[edit]

Rukeyser was one of the great integrators, seeing the fragmentary world of modernity not as irretrievably broken, but in need of societal and emotional repair.

— Adrienne Rich, Essays on Art in Society, A Human Eye

Rukeyser was active in progressive politics throughout her life. In 1933, she covered the Scottsboro case in Alabama, then worked for the International Labor Defense, which handled the defendants' appeals. She was jailed during this time "for fraternizing with African Americans" and contracted typhoid fever in while in jail.[9] She wrote for the Daily Worker and a variety of publications, including Decision and Life & Letters Today, for which she covered the People's Olympiad (Olimpiada Popular, Barcelona), the Catalan government's alternative to the Nazis' 1936 Berlin Olympics. While she was in Spain, the Spanish Civil War broke out, the basis of her book Mediterranean. Most famously, she traveled to Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, to investigate the recurring silicosis among miners there, which resulted in her poem sequence The Book of the Dead.[9] During and after World War II, she gave a number of striking public lectures, published in her The Life of Poetry (excerpts here). For much of her life, she taught university classes (at Sarah Lawrence[8] and led workshops, but she never became a career academic.

In the 1940s, Rukeyser was investigated by the FBI under the House on Un-American Activities Committee for her Leftist activist work,[10] even though she was never a registered member of the Communist party.[11] She was "monitored by the FBI from 1937 until the mid-1970s" after working for only one year (1942-43) with the Office of War Information.[12]

In 1996, Paris Press reissued The Life of Poetry, which was published in 1949 but had fallen out of print.[13] In a publisher's note, Jan Freeman called it a book that "ranks among the most essential works of twentieth century literature."[14] In it Rukeyser makes the case that poetry is essential to democracy, essential to human life and understanding.

In the 1960s and 1970s, when Rukeyser presided over PEN's American center, her feminism and opposition to the Vietnam War drew a new generation to her poetry. The title poem of her last book, The Gates, is based on her unsuccessful attempt to visit Korean poet Kim Chi-Ha on death row in South Korea. In 1968, she signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[15] She was also "arrested and jailed in Washington, D.C., for protesting the Vietnam War."[8]

In addition to her poetry, she wrote a fictionalized memoir, The Orgy, plays and screenplays, and translated work by Octavio Paz and Gunnar Ekelöf. She also wrote biographies of Josiah Willard Gibbs, Wendell Willkie, and Thomas Hariot. Andrea Dworkin worked as her secretary in the early 1970s. Also in the 1970s she served on the Advisory Board of the Westbeth Playwrights Feminist Collective, a New York City based theatre group that wrote and produced plays on feminist issues.

Rukeyser died in New York on February 12, 1980, from a stroke, with diabetes as a contributing factor. She was 66.

Personal life[edit]

At 22, Rukeyser accompanied George and Elizabeth Dublin Marshall on a trip to Europe in 1936, working as their assistant while they researched "cooperatives in England, Scandinavia, and Russia."[16] There, she spent a month in England meeting with literary figures such as T.S. Eliot, Dorothy Richardson, and H.D., the latter whom she continued to correspond with throughout her life.[16] Robert Herring, one of the owners and editors of Life and Letters Today (a literary magazine), "asked Rukeyser to fill in for a colleague and cover the People's Olympics,"[16] which is why she traveled to Spain.

Rukeyser had romantic and sexual relationships with both men and women throughout her life, most notably with her editor Monica McCall, which lasted about thirty years.[7] She also likely had a relationship with the photographer Berenice Abbott.[17] Shortly before her death, Rukeyser had "agreed to participate in the lesbian poetry reading at the 1978 MLA convention,"[18] but cancelled due to illness. Rukeyser never defined her sexuality, and has been described as fluid and mutable.[19]

At some point, Rukeyser married and divorced Glynn Collins (a painter) in the span of six weeks.[8]

Rukeyser had a son in 1947, Bill (né Laurie) Rukeyser, with Donnan Jeffers (son of Robinson Jeffers). However, she raised Bill as a single parent and did not disclose his father's identity to him until he was twelve years old.[19] Bill is the executor of Rukeyser's literary estate.[19] Rukeyser also has a granddaughter (born after she died): the writer Rebecca Rukeyser.[20]

Awards[edit]

- Yale Younger Poets Award (1935) with Theory of Flight

- Harriet Monroe Poetry Award (the first)

- Levinson Prize

- Copernicus Prize

- Guggenheim Fellowship

Works[edit]

- Rukeyser's original collections of poetry

- Theory of Flight. Foreword by Stephen Vincent Benet. New Haven: Yale Uni. Press, 1935. Won the Yale Younger Poets Award in 1935.

- Mediterranean. Writers and Artists Committee, Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy, 1938.

- U.S. 1: Poems. Covici, Friede, 1938.

- A Turning Wind: Poems. Viking, 1939.

- The Soul and Body of John Brown. Privately printed, 1940.

- Wake Island. Doubleday, 1942.

- Beast in View. Doubleday, 1944.

- The Green Wave: Poems. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1948. Includes translations of Octavio Paz poems and rari.

- Orpheus. Centaur Press, 1949. With the drawing "Orpheus" by Picasso.

- Elegies. New Directions, 1949.

- Selected Poems. New Directions, 1951.

- Body of Waking: Poems. NY: Harper, 1958. Includes translated poems of Octavio Paz.

- Waterlily Fire: Poems 1935-1962. NY: Macmillan, 1962.

- The Outer Banks. Santa Barbara CA: Unicorn, 1967. 2nd rev. ed., 1980.

- The Speed of Darkness: Poems. NY: Random House, 1968.

- 29 Poems. Rapp & Whiting, 1972.

- Breaking Open: New Poems. Random House, 1973.

- The Gates: Poems. NY: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

- Fiction by Rukeyser

- Savage Coast : A Novel. Feminist Press, 2013.[21]

- Plays by Rukeyser

- The Middle of the Air. Produced in Iowa City, IA, 1945.

- The Colors of the Day: A Celebration of the Vassar Centennial. Produced in Poughkeepsie, NY, at Vassar College, June 10, 1961.

- Houdini. Produced in Lenox, MA, at Lenox Arts Center, July 3, 1973.[22] Published as Houdini: A Musical, Paris Press, 2002.[23]

- Children's books

- Come Back, Paul. Harper, 1955.[24]

- I Go Out. Harper, 1961. Illustrated by Leonard Kessler. [25]

- Bubbles. Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967.[26]

- Mazes. Simon & Schuster, 1970. Photography by Milton Charles.[27]

- More Night. Harper & Row, 1981. Illustrated by Symeon Shimin. [28]

- Memoirs by Rukeyser

- The Orgy: An Irish Journey of Passion and Transformation. London: Andre Deutsch, 1965; NY: Pocket Books, 1966; Ashfield, MA: Paris Press, 1997.[29]

- Works of criticism by Rukeyser

- The Life of Poetry. NY: Current Books, 1949; Morrow, 1974; Paris Press, 1996.[30]

- Biographies by Rukeyser

- Willard Gibbs: American Genius, 1942. Reprinted by the Ox Bow Press, Woodbridge CT. Biography of Josiah Willard Gibbs, physicist. [25]

- One Life. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1957. Biography of Wendell Willkie.

- The Traces of Thomas Hariot. NY: Random House, 1971. Biography of Thomas Hariot.

- Translations by Rukeyser

- Selected Poems of Octavio Paz. Indiana University Press, 1963. Rev. ed. published as Early Poems 1935-1955, New Directions, 1973.

- Sun Stone. Octavio Paz. New Directions, 1963.

- Selected Poems of Gunnar Ekelöf. With Leif Sjöberg. Twayne, 1967.

- Three Poems. Gunnar Ekelöf. T. Williams, 1967.

- Uncle Eddie's Moustache. Bertolt Brecht. 1974.

- A Molna Elegy: Metamorphoses. Gunnar Ekelöf. With Leif Sjöberg. 2 volumes. Unicorn Press, 1984.

- Edited collections of Rukeyser's works

- The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser. McGraw, 1978.

- Out of Silence: Selected Poems. Edited by Kate Daniels. Triquarterly Books, 1992.

- A Muriel Rukeyser Reader. Norton, 1994.

- The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

In other media[edit]

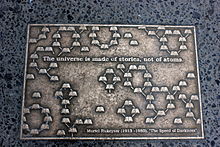

In the television show Supernatural, Metatron the angel quotes an excerpt of Rukeyser's poem "Speed of Darkness": "The Universe is made of stories, not of atoms."

Jeanette Winterson's novel Gut Symmetries (1997) quotes Rukeyser's poem "King's Mountain".

Rukeyser's translation of a poem by Octavio Paz was adapted by Eric Whitacre for his choral composition "Water Night." John Adams set one of her texts in his opera Doctor Atomic, and Libby Larsen set the poem "Looking at Each Other" in her choral work Love Songs.

Writer Marian Evans and composer Chris White are collaborating on a play about Rukeyser, Throat of These Hours, titled after a line in Rukeyser's Speed of Darkness.

The JDT: Journal of Narrative Theory, a publication from Eastern Michigan University, dedicated a special issue to Rukeyser in Fall 2013.[31]

Rukeyser's 5-poem sequence "Käthe Kollwitz" (The Speed of Darkness, 1968, Random House)[32] was set by Tom Myron in his composition "Käthe Kollwitz for Soprano and String Quartet," "written in response to a commission from violist Julia Adams for a work celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Portland String Quartet in 1998."[33]

Rukeyser's poem "Gunday's Child" was set to music by the experimental rock band Sleepytime Gorilla Museum.

References[edit]

- ^ Gander, Catherine (2013). Muriel Rukeyser and Documentary: The Poetics of Connection. Edinburgh UP. ISBN 9780748670536.

- ^ "On "To Be a Jew in the Twentieth Century"". Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ^ Unger, Leonard; Litz, A. Walton; Weigel, Molly; Bechler, Lea; Parini, Jay (1974-01-01). American writers: a collection of literary biographies. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684197855. OCLC 1041142.

- ^ Wolosky (2010). "What Do Jews Stand For? Muriel Rukeyser's Ethics of Identity". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (19): 199. doi:10.2979/nas.2010.-.19.199.

- ^ Wolosky (2010). "What Do Jews Stand For? Muriel Rukeyser's Ethics of Identity". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (19): 199. doi:10.2979/nas.2010.-.19.199.

- ^ Wolosky (2010). "What Do Jews Stand For? Muriel Rukeyser's Ethics of Identity". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (19): 199. doi:10.2979/nas.2010.-.19.199.

- ^ a b "Eric Keenaghan, Total Imaginative Response: Five Undergraduate Studies from "The Lives of Muriel Rukeyser"". Muriel Rukeyser Website. 2020-09-05. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b c d "Muriel Rukeyser". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ a b Kennedy-Epstein, Rowena (Summer 2013). ""Her Symbol Was Civil War": Recovering Muriel Rukeyser's Lost Spanish Civil War Novel". Modern Fiction Studies. 59 (2): 416–439 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Muriel Rukeyser Part 1 of 1". FBI. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ Wolosky (2010). "What Do Jews Stand For? Muriel Rukeyser's Ethics of Identity". Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues (19): 199. doi:10.2979/nas.2010.-.19.199.

- ^ Kennedy-Epstein, Rowena (2019-05-01). "So Easy to See: Muriel Rukeyser and Berenice Abbott's unfinished collaboration". Literature & History. 28 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1177/0306197319829379. ISSN 0306-1973.

- ^ "Jan Freeman - Artist". MacDowell. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1996). The Life of Poetry. Paris Press. ISBN 0963818333.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" January 30, 1968 New York Post

- ^ a b c Kennedy-Epstein, Rowena (2013). ""'Whose fires would not stop': Muriel Rukeyser and the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1976"". Journal of Narrative Theory. 43 (3): 384–414. ISSN 1549-0815.

- ^ Kennedy-Epstein, Rowena (2019-05-01). "So Easy to See: Muriel Rukeyser and Berenice Abbott's unfinished collaboration". Literature & History. 28 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1177/0306197319829379. ISSN 0306-1973.

- ^ Bulkin, Elly (1979). ""A Whole New Poetry Beginning Here": Teaching Lesbian Poetry". College English. 40 (8): 874–888. doi:10.2307/376524. ISSN 0010-0994.

- ^ a b c "Yearning for My Grandmother Muriel Rukeyser (and Grappling With Her Legacy)". Literary Hub. 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ "Profiles". berlin.bard.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel; Kennedy-Epstein, Rowena (2014-01-01). Savage coast. ISBN 9781558618206. OCLC 887938693.

- ^ "Muriel Rukeyser". Poetry Foundation. 2017-03-07. Retrieved 2017-03-08.

- ^ Spangler, David; Rukeyser, Muriel (2002-01-01). Houdini: a musical. Ashfield, Mass.: Paris Press. ISBN 1930464045.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1955). Come back, Paul. New York: Harper. ISBN 9780916384111.

- ^ a b Rosenbaum, Judith (March 20, 2009). "Muriel Rukeyser". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1967). Bubbles. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. ISBN 9780152128302.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel; Charles, Milton (1970-01-01). Mazes. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 067165151X. OCLC 113139.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1981). More Night. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060251277.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1965). The Orgy. London: Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-9638183-2-5.

- ^ Rukeyser, Muriel (1949). The Life of Poetry. New York City: Current Books inc. ISBN 0-9638183-3-3.

- ^ "Muriel Rukeyser: A Living Archive". Eastern Michigan University. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Käthe Kollwitz". murielrukeyser.emuenglish.org. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ "Darkness & Light, Vol. 3". dramonline.org. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

Further reading[edit]

- Barber, David S. "Finding Her Voice: Muriel Rukeyser's Poetic Development." Modern Poetry Studies 11, no. 1 (1982): 127–138

- Barber, David S. "'The Poet of Unity': Muriel Rukeyser's Willard Gibbs." CLIO: A Journal of Literature, History and the Philosophy of History 12 (Fall 1982): 1–15; "Craft Interview with Muriel Rukeyser." New York Quarterly 11 (Summer 1972) and in The Craft of Poetry, edited by William Packard (1974)

- Daniels, Kate, ed. Out of Silence: Selected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (1992), and "Searching/Not Searching: Writing the Biography of Muriel Rukeyser." Poetry East 16/17 (Spring/Summer 1985): 70–93

- Gander, Catherine. Muriel Rukeyser and Documentary: The Poetics of Connection (EUP, 2013)

- Gardinier, Suzanne. "'A World That Will Hold All The People': On Muriel Rukeyser." Kenyon Review 14 (Summer 1992): 88–105

- Herzog, Anne E. & Kaufman, Janet E. (1999) "But Not in the Study: Writing as a Jew" in How Shall We Tell Each Other of the Poet?: The Life and Writing of Muriel Rukeyser.

- Jarrell, Randall. Poetry and the Age (1953)

- Kertesz, Louise. The Poetic Vision of Muriel Rukeyser (1980)

- Levi, Jan Heller, ed. A Muriel Rukeyser Reader (1994)

- Myles, Eileen, "Fear of Poetry." Review of The Life of Poetry, The Nation (April 14, 1997). This page includes several reviews, with much biographical information.

- Pacernick, Gary. "Muriel Rukeyser: Prophet of Social and Political Justice." Memory and Fire: Ten American Jewish Poets (1989)

- Rich, Adrienne. "Beginners." Kenyon Review 15 (Summer 1993): 12–19

- Rosenthal, M.L. "Muriel Rukeyser: The Longer Poems." In New Directions in Prose and Poetry, edited by James Laughlin. Vol. 14 (1953): 202–229;

- Rudnitsky, Lexi. "Planes, Politics, and Protofeminist Poetics: Muriel Rukeyser's Theory of Flight and The Middle of the Air," Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, v.27, n.2 (Fall 2008), pp. 237–257, DOI: 10.1353/tsw.0.0045

- "A Special Issue on Muriel Rukeyser." Poetry East 16/17 (Spring/Summer 1985);

- Thurston, Michael, "Biographical sketch." Modern American Poetry, retrieved January 30, 2006

- Turner, Alberta. "Muriel Rukeyser." In Dictionary of Literary Biography 48, s.v. "American Poets, 1880–1945" (1986): 370–375; UJE;

- "Under Forty." Contemporary Jewish Record 7 (February 1944): 4–9

- Ware, Michele S. "Opening 'The Gates': Muriel Rukeyser and the Poetry of Witness." Women's Studies: An Introductory Journal 22, no. 3 (1993): 297–308; WWWIA, 7.

External links[edit]

- Muriel Rukeyser: A Living Archive Ongoing project by Eastern Michigan University featuring creative content by Rukeyser as well as critical resources and creative responses by artists and scholars.

- Muriel Rukeyser papers, 1844–1986 at the Library of Congress

- Guide to the Muriel Rukeyser Papers at the Vassar College Archives and Special Collections Library

- Muriel Rukeyser by Michael Thurston, Modern American Poetry, retrieved January 30, 2006

- "The Book of the Dead" by Muriel Rukeyser

- Muriel Rukeyser's FBI files

- PennSound page (audio recordings).