User:Sadi Carnot/Sandbox4

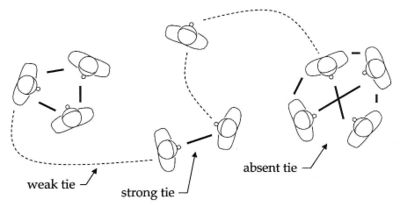

In mathematical sociology, interpersonal ties are defined as information-carrying connections between people. Interpersonal ties, generally, come in three varieties: strong, weak, or absent. Weak social ties, it is argued, are responsible the majority of the embeddedness and structure of social networks in society as well as the transmission of information through these networks. Specifically, more novel information flows to individuals through weak than through strong ties. Because our close friends tend to move in the same circles that we do, the information they receive overlaps considerably with what we already know. Acquaintances, by contrast, know people that we do not, and thus receive more novel information.[1]

History[edit]

One the of the earlist writers to discuss the effects of ties between people was the German scientist and philospher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, where in his classic 1809 novella Elective Affinities speaks of the marriage tie and by analogy shows how strong marriage unions are similar in character to that by which the particles of quicksilver find a unity together though the process of chemical affinity.

In 1954, the Russian mathematical psychologist Anatol Rapoport commented on the "well-known fact that the likely contacts of two individuals who are closely acquainted tend to be more overlapping than those of two arbitraily selected individuals." This arguement became one of the corner stones of the probabilistic approach to network theory.

In 1973, stimulate by the work of Rapoport, the American sociologist Mark Granovetter's published The Strength of the Weak Ties, which is recongnized as one of the most influential sociology papers ever written.[2] During his freshman year at Harvard, Granovetter was intreged by the classic chemistry lesson demonstrating how "weak" hydrogen bonds hold huge water molecules together, which are themselves held together by "strong" covalent bonds. In Granovetter's view, this was the basic model of society:

This picture stuck with him until graduate school years to inspire his first manuscript on the importance of the weak social ties in human life. He mailed it out in August 1969 to the American Sociological Review. It was rejected, because, according to two anonymous referees, the manuscript should not be published for "an endless series of reasons that immediately come to mind." In 1972, nevertheless, Granovetter submitted a shortened version to the American Journal of Sociology, and it was finally published in May 1973. According to Current Contents, by 1986, the Weak Ties paper had become a citation classic, being on of the most cited papers in sociology.

Tie destinctions[edit]

Inclusive in the definition of abscent ties, according to Granovetter, are those relationships or ties with out substantial sugnificance, such as "nodding" relationships between people living on the same street, or the "tie", for example, to the vendor from whom one coustomarily buys a morning paper. Moreover, the fact that two people may know each other by name does not necessarily qualify the existence of a weak tie, e.g. if their interaction is negligible the tie may be of the absent variety.

The "strength" of an interpersonal tie is a linear combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize each tie.[3]

Social networks[edit]

In social network theory, social relationships are viewed in terms of nodes and ties. Nodes are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors. There can be many kinds of ties between the nodes. In its most simple form, a social network is a map of all of the relevant ties between the nodes being studied.

Weak tie hypothesis[edit]

The "weak tie hypothesis" argues, using a combination of probability and mathematics, as originally stated by Anatol Rapoport in 1957, that if A is linked to both B and C, then there is a greater than chance probability that B and C are linked to each other:[4]

Thus, if A is strongly tied to both B and C, then according to probability arguements, the B-C tie is always present. The absence of the B-C tie, in this situation, would create, according to Granovetter, what is called the forbidden triad. In other words, the B-C tie, according to this logic, is always present, whether weak or strong, given the other two strong ties. From this basis, other theories can be formulated and tested, e.g. that the diffusion of information, such as rumors, may tend to be dampened by strong ties, and thus flow more easily through weak ties.

Positive ties and negative ties[edit]

Starting in the late 1940s, Anatol Rapoport and others developed a probabilistic approach to the characterization of large social networks in which the nodes are persons and the links are acquaintanceship. During these years, formulas were derived that connected local parameters such as closure of contacts, such as the supposed existence of the B-C tie, to the global network property of connectivity.[5]

Moreover, acquaintanceship, in most cases, is a positive tie, but what about negative ties such as animosity among persons? To tackle this problem, graph theory, which is the mathematical study of abstract representations of networks of points and lines, can be extended to include these two types of links and thereby to create models that represent both positive and negative sentiment relations. This effort led to an important and non-obvious Structure Theorem, as developed by Dorwin Cartwright and Frank Harary in 1956, which says that if a network of interrelated positive and negative ties is balanced, e.g. as illustrated by the psychological consistency of "my friend's enemy is my enemy", then it consists of two subnetworks such that each has positive ties among its nodes and negative ties between nodes in distinct subnetworks.[6] The imagery here is of a social system that splits into two cliques. There is, however, a special case where one of the two subnetworks is empty, which might occur in very small networks.

In these two developments we have mathematical models bearing upon the analysis of structure. Other early influential developments in mathematical sociology pertained to process. For instance, in 1952 Herbert Simon produced a mathematical formalization of a published theory of social groups by constructing a model consisting of a deterministic system of differential equations. A formal study of the system led to theorems about the dynamics and the implied equilibrium states of any group.

Recent views[edit]

In the early 1990s, American social economist James Montgomery contributed to economic theories of network structures in labor market. In 1991, Montgomery incorporated network structures in an adverse selection model to analyze the effects of social networks on labor market outcomes.[7] In 1992, Montgomery explored the role of “weak ties”, which he defined as non-frequent and transitory social relations, in labor market.[8][9] He demonstrates that weak ties are positively related to higher wages and higher aggregate employment rates.

References[edit]

- ^ Granovetter, M.D. (2004). "The Impact of Social Structures on Economic Developement." Journal of Economic Perspectives (Vol 19 Number 1, pp. 33-50).

- ^ Barabasi, Albert-Laszlo (2003). Linked - How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What it Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. Plume. ISBN 0452284392.

- ^ Granovetter, M.S. (1973). "The Strength of Weak Ties", Amer. J. of Sociology, Vol. 78, Issue 6, May 1360-80.

- ^ *Rapoport, Anatol. (1957). "Contributions to the Theory of Random and Biased Nets." Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 19: 257-277.

- ^ Rapoport, Anatol. (1957). "Contributions to the Theory of Random and Biased Nets." Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 19: 257-277.

- ^ Cartwright, Dorwin & Harary, Frank. (1956). "Structural Balance: A Generalization of Heider's Theory." Psychological Review 63:277-293.

- ^ Montgomery, J.D. (1991). “Social Networks and Labor-Market Outcomes: Toward an Economic Analysis,” American Economic Review, 81 (Dec.): 1408-18.

- ^ Montgomery, J.D. (1992). “Job Search and Network Composition: Implications of the Strength-of-Weak-Ties Hypothesis,” American Sociological Review, 57 (Oct.): 586-96.

- ^ Montgomery, J.D. (1994). “Weak Ties, Employment, and Inequality: An Equilibrium Analysis,” American Journal of Sociology, 99 (Mar.): 1212-36.

Further reading[edit]

- Granovetter, M.S. (1983). "The Strength of the Weak Tie: Revisited" [PDF], Sociological Theory, Vol. 1, 201-33.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Caves, Clusters, and Weak Ties: The Six Degrees World of Inventors - Harvard Business School, Nov. 28, 2004

- The Weakening of Strong Ties - Ross Mayfield, Sept. 15, 2003