User:Shonebrooks/Archibald Campbell (abolitionist)

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

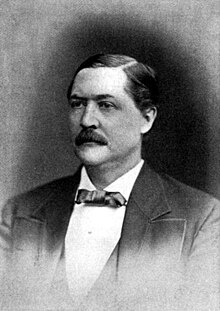

Archibald W. Campbell | |

|---|---|

Archibald W. Campbell | |

| Born | Archibald W. Campbell April 4, 1833 Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | February 13, 1899 (aged 65) Webster Groves, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place | God's Acre Cemetery, Bethany, West Virginia, U.S. 40°12′20″N 80°32′57″W / 40.205443°N 80.5493055°W |

| Other names | Archie Campbell |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer, Publisher, Abolitionist |

| Known for | Promoting the creation of West Virginia as a slave-free state |

| Spouses | Annie W. Crawford

(m. 1864, died)

|

| Relatives | Alexander Campbell, Uncle |

Archibald Campbell (/kæmˈbʊl/; April 4, 1833 – February 13, 1899) was an abolitionist, journalist, and member of the nascent Republican Party. He was born in Ohio in 1833 and raised in the western portion of Virginia. He met future Secretary of State, William H. Seward while studying law in New York. Influenced by Seward, Campbell joined the Republican Party. He bought the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer in 1856, promoting it to a position of great influence in Virginia. Campbell used the influence of his newspaper to advocate for the creation of West Virginia against the backdrop of the Civil War.[1]

Early life

[edit]Born on April 4, 1833 in Jefferson County, Ohio, Campbell's parents were Archibald W. and Phebe Clapp.[2] His father's older brother was the influential Christian reformer, Alexander Campbell. Young Archibald grew up in the vicinity of Bethany, Virginia where his family had moved and where his uncle had started Bethany College, while his father served the community as a physician. Graduating from Bethany College in 1852, he subsequently studied Law in New York at Hamilton College Law School. There he met William H. Seward, and under his influence joined the newly formed Republican Party and took up the abolitionist cause.[1]

Public life

[edit]Partnering with John F. McDermot to buy the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer in 1856, Campbell assumed the role of the paper's editor in October of that year. He leveraged the paper's strong circulation over the next couple years to espouse his views against slavery.[3]

In 1859, Campbell lobbied Republic Party leaders to hold its 1860 national convention in Wheeling, but was unsuccessful. At the convention which was held in Chicago, Campbell initially backed his mentor Seward in the latter's pursuit of the party's presidential nomination. With insufficient support for Seward within the party, Campbell subsequently endorsed the nomination of Abraham Lincoln.

Campbell viewed the policies of Virginia’s state government as harmful to the residents of northwestern Virginia. When the Ordinance of Secession was adopted at the Convention of 1861, Campbell again turned to the power of the press by using his newspaper's popularity to promote the perceived benefits western Virginians might enjoy by establishing new state. He also used his influence to champion the abolition of slavery as a provision in the first constitution of West Virginia.[4]

During and after the Civil War, Campbell viewed himself as a staunch Republican. But that allegiance was tested when he felt Party interests did not align with what he felt was best for West Virginia. By 1880, his vocal disagreements with party leaders on several issues had nearly resulted in his expulsion from the national convention. Despite the threat, he was able to lend his support to his friend, James A. Garfield's presidential nomination. Campbell, himself, was content to avoid seeking public office or government appointment.[1]

Personal life

[edit]Campbell married Annie W. Crawford in Wheeling, West Virginia, on March 10, 1864. Annie subsequently gave birth to a son, and later, a daughter. After Annie later died, Campbell took a second wife named Mary H., whose surname is unknown. One daughter is known to have been born to the couple.[1]

Death and legacy

[edit]Campbell gradually withdrew from his day-to-day editing and publishing responsibilities at the Intelligencer to allocate more time to other business pursuits and personal interests. He suffered a stroke and died on February 13, 1899 while visiting his sister in Missouri. He is interred at Greenwood Cemetery in Wheeling.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e MacGregor, Douglas. "Archibald W. Campbell (1833–1899)- Encyclopedia Virginia". Library of Virginia. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Campbell, Selina (1882), "XXI", Home Life and Reminiscences of Alexander Campbell, J. Burns, p. 486, retrieved 16 April 2024,

The Doctor, A. W. Campbell, with his Christian wife, (nee Phebe Clapp,)

- ^ Willey, William (1901), "XV", An Inside View of the Formation of the State of West Virginia, News Publishing Company, p. 202, retrieved 16 April 2024,

When young "Archie" Campbell came into control of the Intelligencer he succeeded a brother of Prof. Pendleton, a lawyer and a Southern Democrat. The young editor, wiser than his years, began by slow but steady approaches a campaign of aggression against slavery.

- ^ Curtis, Francis (1904), "The Republican Party Press", The Liberal-Republican movement; Conventions, platforms, campaign, and election of 1872, G. P. Putnam's Sons, p. 497, retrieved 16 April 2024,

Another slave State furnished a journal of pronounced Republicanism which was quoted often by the party's papers and statesmen in the North. This was the Wheeling Intelligencer, which, under the editorship of Archibald W. Campbell, struck telling blows for freedom in the party's formative days. Campbell and the Intelligencer were powerful factors in the fight for the Union in which the Old Dominion was rent and its western counties erected into a state under the title of West Virginia.

External links

[edit]