User:Swadge2/Bellum Iugurthinum

{{Italic title}}

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

New article name goes here new article content ...

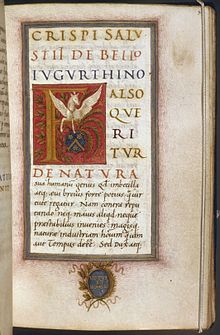

c. 1490 manuscript of De Bello Iugurthino | |

| Author | Sallust |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Published | c. 41 BC |

The Bellum Iugurthinum is an historical monograph by the Roman author Sallust, published in or around 41 BC.[1] It describes the events of the Jugurthine War (112–106 BC) between the Roman Republic and King Jugurtha of Numidia. Sallust alleges that Jugurtha was able to repeatedly bribe corrupted Roman officials in the war, and thought that this was indicative of a broader moral decline in the late Republic. In this way, it is thematically similar to his earlier Bellum Catilinae. The Bellum Iugurthinum is the main historical source for the Jugurthine War.

Summary[edit]

Sallust begins with a philosophical introduction in which he discusses the nature of man and history, and laments that while the men of old tried to equal their ancestors "in virtue and labor", his contemporaries only sought "riches and extravagance", and so "intrigue and dishonesty" were rife.[2] This theme is repeated throughout the work.

He begins by introducing the kingdom of Numidia. Its founder, Masinissa, had served with Scipio Africanus in the Second Punic War. For his service, he was granted captured Roman lands to form Numidia. He was succeeded by his son, Micipsa. Micipsa had two sons, Adherbal and Hiempsal, and an illegitimate nephew, Jugurtha. Sallust says that Jugurtha was popular among his countrymen, and so a worried Micipsa sent him to serve under Scipio Aemilianus at the Siege of Numantia, hoping that Jugurtha would be killed in battle.[3] But these hopes failed to materialise. Jugurtha survived, and significantly, Sallust says that Jugurtha made friends with his corrupted Roman comrades, who encouraged him to usurp the throne of Numidia at Micipsa's death.[4] Von Fritz argues that it is highly unlikely that Sallust received word of these conversations, if they did indeed occur.[5] Following the fall of Numantia, Jugurtha returned to Numidia, and was adopted by Micipsa.

At his death, Micipsa left the kingdom to Adherbal, Hiempsal, and Jugurtha. At a conference to discuss their shared administration of the kingdom, Hiempsal insulted Jugurtha,[6] and he was soon assassinated by Jugurtha's agents.[7] Adherbal fled in fear to Rome to appeal for the Senate's help. But Sallust says that Jugurtha also sent emissaries, with great bribes.[8] The Senate decided then, according to Sallust because of this bribery, to divide Numidia between Adherbal and Jugurtha and not intervene militarily.[9]

Relations between Jugurtha and Adherbal broke down and Jugurtha besieged Adherbal at Cirta. Adherbal sent two ambassadors through Jugurtha's lines to Rome, to appeal for their help.[10] Sallust claims that Jugurtha's earlier bribery ensured that no decisive action would be taken; the Senate sent three aged ambassadors.[11] The ambassadors met Jugurtha in Utica, and warned him of the Senate's power but departed. The population of Italian traders that lived in Cirta, hearing of this, persuaded Adherbal to surrender, believing that they and he would be spared. But, once he had surrendered, Adherbal was killed by Jugurtha, and Jugurtha's troops massacred Cirta's population, including the Italian traders.[12] This matter came to the Senate, and Sallust says that those who had been bribed by Jugurtha before attempted to obstruct proceedings by protracting the debates. But Gaius Memmius, then tribune of the plebs, inflamed the passions of the people, and the Senate decided to send Lucius Calpurnius Bestia to Numidia.[13]

Bestia raised an army, but shortly after arriving agreed to Jugurtha's surrender on lenient terms; Sallust alleges that this was due to bribery, and effective because of Bestia's avarice.[14] These events became known in Rome, and Gaius Memmius once again stirred up the people.[15] Lucius Cassius was therefore sent to bring Jugurtha to Rome, as Memmius hoped to prosecute Bestia for accepting bribes.[16] But once Cassius and Jugurtha had returned to Rome, the tribune Gaius Baebius used his powers to prevent Jugurtha from giving testimony. Sallust says that Baebius had been bribed as well.[17] While in Rome, Jugurtha also arranged the assassination of Massiva, a rival for the Numidian throne who was petitioning the Senate to grant him the kingdom.[18]

Sallust says that the war resumed, and that the Senate sent Spurius Postumius Albinus to Africa to continue waging it. Albinus made little progress however, and Sallust reports that some speculated that he had been bribed.[19] Albinus had to leave Africa for the comitia, and so left his army in the charge of his brother Aulus Postumius Albinus. Aulus attempted to besiege Jugurtha's treasury, and was lured by Jugurtha away from the city on hopes of a surrender. Jugurtha then surrounded Aulus' camp at night, according to Sallust alleges after bribing some of Aulus' soldiers. Half of Aulus' army were killed, and the other half were sent under the yoke, and Aulus negotiated a surrender with Jugurtha that gave him control of all of Numidia.[20] These events were received with great displeasure in Rome. Albinus returned to Africa to try and put things right, but Sallust says he found the troops there to be corrupted and so was unable to make any action.[21]

At this time, Sallust says that Gaius Mamilius Limetanus formed a commission to investigate the behaviour of the nobility in the war.[22] Sallust criticises the commission, and then digresses into a discussion of corruption and factionalism in the Roman Republic.[23] He traces this to the destruction of Carthage, arguing that a fear of Carthage (metus Punicus or metus hostilis, fear of an external enemy) had kept the people and nobility in stable relations. This argument was common at the time.

Sallust returns to the war and says that Quintus Metellus, as consul, raised a new army and set off for Numidia. Metellus too, according to Sallust, found the Roman troops to be corrupted, and so imposed strict rules on his army.[24] Jugurtha offered surrender to Metellus twice, but Metellus was distrustful.[25] The forces of Jugurtha and those of Metellus eventually met in a chaotic battle, which Jugurtha was eventually the loser of, though the king escaped.[26] Metellus proceeded through Numidia, destroying towns and fortresses, while Jugurtha stalked the Roman army and made attacks by ambush.[27] Metellus besieged the city of Zama, hoping to force Jugurtha into a battle, but was unsuccessful; the latter instead attacked the Roman camp during the siege. Hearing the attack, Metellus returned to the camp and forced Jugurtha's army to retreat, but had to suspend the siege.[28] Metellus resumed the next day, and Jugurtha again attacked the camp, though was driven away. Metellus saw that the siege would not be successful, and so abandoned it.[29]

Metellus attempted to negotiate a surrender with Jugurtha via Jugurtha's follower Bomilcar, and while Jugurtha began to surrender wealth, arms, and the Roman deserters, he lost heart and so would not surrender himself.[30]

Half of Metellus' army was led by Gaius Marius, and at this time, Sallust says that an augur had given him a very positive prediction of his future.[31] Marius desired to become consul, and saw this as confirmation that he should act on these desires. He talked to Metellus about this, but Metellus was dismissive, which Sallust says hardened Marius' resolve.[32] Marius attempted to increase his popularity among his soldiers by relaxing discipline, and among the merchants by claiming that he could finish the war far more quickly than Metellus.[32]

At this time, Jugurtha had resumed the war, and Sallust says he compelled the population of Vacca to ambush and slaughter the garrison that Metellus had stationed in the city.[33] Metellus assembled his army and marched on the city. Sallust says that Metellus positioned the captured Numidian cavalry at the front of the army so that the people of Vacca, thinking the army to be Jugurtha's, opened their gates.[34]

Sallust says that simultaneously, Bomilcar began plotting to kill Jugurtha, and selected Nabdalsa for an accomplice. Nabdalsa became apprehensive, and so Bomilcar sent him an encouraging letter.[35] An assistant of Nabdalsa found and read the letter, and disclosed the plot to Jugurtha.[36] Sallust says that Jugurtha put to death Bomilcar and some number of unnamed others.[37]

Metellus heard of these events, and so prepared for a fresh offensive. He sent Marius to Rome as Marius had requested. Sallust says that in Rome, Metellus' nobility had become a reason for dislike, while Marius' excellence was exaggerated by tribunes on the basis of his common birth.[38]

In Numidia, Sallust says that Jugurtha was anxious and irresolute, many of his officers having been either executed or having defected to the Romans. Metellus met Jugurtha in battle, and Jugurtha was defeated, but escaped to the city of Thala with some deserters.[39] Metellus then set out for Thala. Sallust says that Jugurtha fled the city with his family and treasure, when he saw that Metellus had arrived. Metellus commenced a siege on the city, which Sallust says lasted forty days before Roman victory.[40] Sallust says that Jugurtha fled further, to the territory of the Gaetuli.[41] He also began to court Bocchus, king of Mauretania, encouraging him to enter into military alliance.[42] Bocchus eventually agreed, and the two kings marched on Cirta, where Metellus stored his plunder and prisoners.[43]

While Metellus camped near Cirta, anticipating the siege, he received word from Rome, that Marius, who was successful in his bid for the consulship, had been assigned the province of Numidia. Sallust describes that this greatly upset Metellus.[44] Sallust says that as Metellus waited for Marius to arrive, he protracted the war by back-and-forth negotiation with Bocchus and Jugurtha.[45]

Sallust then records a speech he claims Marius made before the people, replete with extensive criticism of the nobility and their handling of the war.[46] Invigorated by this speech, the people made preparations for Marius' war effort in Numidia. Sallust also describes that

Veracity[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ J. C., Rolfe (2012-07-10). "Introduction". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sallust. "Jug. 4".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sallust. "Jug. 7".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sallust. "Jug. 8".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ von Fritz, Kurt (1943). "Sallust and the Attitude of the Roman Nobility at the Time of the Wars against Jugurtha". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 74: 134–168. doi:10.2307/283595. JSTOR 283595 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Jug. 11

- ^ Jug. 13

- ^ Jug. 13

- ^ Jug. 16

- ^ Jug. 24

- ^ Jug. 25

- ^ Jug. 26

- ^ Jug. 27

- ^ Jug. 29

- ^ Jug. 30

- ^ Jug. 32

- ^ Jug. 34

- ^ Jug. 35

- ^ Jug. 36

- ^ Jug. 38

- ^ Jug. 39

- ^ Jug. 40

- ^ Jug. 41-42

- ^ Jug. 45

- ^ Jug. 47

- ^ Jug. 54

- ^ Jug. 55

- ^ Jug. 58

- ^ Jug. 61

- ^ Jug. 62

- ^ Jug. 63

- ^ a b Jug. 65

- ^ Jug. 66

- ^ Jug. 69

- ^ Jug. 70

- ^ Jug. 71

- ^ Jug. 72

- ^ Jug. 73

- ^ Jug. 74-75

- ^ Jug. 76

- ^ Jug. 80

- ^ Jug. 80

- ^ Jug. 81

- ^ Jug. 82

- ^ Jug. 83

- ^ Jug. 85