V2 word order

In syntax, verb-second (V2) word order is a specific restriction on the placement of the finite verb within a given clause or sentence. A V2 clause has the finite verb (the verb inflected for person) in second position with a single major constituent preceding it, which functions as the clause topic.[1]

V2 word order is common across the Germanic languages and is also found in Indo-Aryan Kashmiri, Northeast Caucasian Ingush, Uto-Aztecan O'odham and fragmentarily in Rhaeto-Romansh Sursilvan. Among members of the Germanic family, English, which has predominantly SVO instead of V2 order, is an exception (although certain vestiges of the V2 phenomenon can also be found in English). Germanic languages and Kashmiri differ with respect to word order in embedded clauses.

Most Germanic languages do not normally use the V2 principle in embedded clauses, except in a certain semantic type of clause with certain verbs. Thus, German, Dutch and Afrikaans revert to VF (verb final) word order in embedded clauses. Two Germanic languages, Yiddish and Icelandic, allow V2 in all declarative clauses: main, embedded, and subordinate. Kashmiri has V2 in 'declarative content clauses' but VF order in relative clauses.

Examples

The following examples from German illustrate the V2 principle:

a. Die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park Fußball. the kids played before school in the park football. b. Fußball spielten die Kinder vor der Schule im Park. 'Football played the kids before school in the park.' c. Vor der Schule spielten die Kinder im Park Fußball. 'Before school, played the kids in the park football.' d. Im Park spielten die Kinder vor der Schule Fußball. 'In the park, played the kids before school football.' e. *Vor der Schule Fußball spielten die Kinder im Park. 'Before school football played the kids in the park.' f. *Fußball die Kinder spielten vor der Schule im Park. 'Football the kids played before school in the park.'

(The asterisk * is the standard means employed in linguistics to indicate that the example is grammatically unacceptable.) The sentences a–d, which are all perfectly acceptable, have the finite verb spielten in second position, whereby the major constituent which appears in the first position varies. The e and f sentences are bad because the finite verb no longer appears in second position there, but rather it has been pushed to the third position. The V2 principle allows any major constituent to occupy the first position as long as the second position is occupied by the finite verb.

The following examples from Dutch illustrate the V2 principle further:

a. Ik las gisteren dit boek. I read yesterday this book. b. Dit boek las ik gisteren. 'This book read I yesterday.' c. Gisteren las ik dit boek. 'Yesterday read I this book.' d. *Dit boek ik las gisteren. 'This book I read yesterday.' e. *Gisteren ik las dit boek. 'Yesterday I read this book.'

We again see in sentence a–c that as long as the finite verb (here las) is in second position, the major constituent in first position is variable. When two (or more) major constituents appear before the finite verb as in sentences d and e, the V2 principle is violated and the sentence is bad. Data similar to these examples from German and Dutch could easily be produced for the other Germanic languages.

Non-finite verbs and embedded clauses

Non-finite verbs

The V2 principle regulates the position of finite verbs only; its influence on non-finite verbs (infinitives, participles, etc.) is thus indirect. Non-finite verbs in V2 languages appear in varying positions depending on the language at hand. In German and Dutch, for instance, non-finite verbs appear after the object (if one is present) in clause final position in main clauses, which means OV (object-verb) order is present in a sense. Swedish and Icelandic, in contrast, position non-finite verbs after the finite verb but before the object (if one is present), which means VO (verb-object) order is present. In this regard, it is important to understand that the V2 principle focuses on the finite verb only.

Embedded clauses

(In the following examples, finite verb forms are in bold, non-finite verb forms are in italics and subjects are underlined.)

The V2 principle may or may not be in force in embedded clauses depending on the (Germanic) language at hand. The languages fall into three groups.

Continental Scandinavian languages: Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Faroese

In these languages, the word order of clauses is generally fixed in two patterns of conventionally numbered positions.[2] Both end with positions for (5) non-finite verb forms, (6) objects (7), adverbials.

In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. The finite verb must be in position (2) and sentence adverbs in position (4). The latter include words with meanings such as 'not' and 'always'. The subject may be position (1), but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject is in position (3).

In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint is absent. After the conjunction, the subject must immediately follow; it cannot be replaced by a topical expression. Thus, the first four positions are in the fixed order (1) conjunction, (2) subject, (3) sentence adverb, (4) finite verb

The position of the sentence adverbs is important to those theorists who see them as marking the start of a large constituent within the clause. Thus the finite verb is seen as inside that constituent in embedded clauses, but outside that constituent in V2 main clauses.

- Swedish

main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

SubjectSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. I dag ville Lotte inte läsa tidningen 1 2 3 4 5 6 today wanted Lotte not read the newspaper ... 'Lotte didn't want to read the paper today.' embedded clause b. att Lotte inte ville koka kaffe i dag 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 that Lotte not wanted brew coffee today ... 'that Lotte didn't want to make coffee today'

- Danish

main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

SubjectSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

Finite verbNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. Klaus er ikke kommet 1 2 4 5 Klaus is not come ...'Klaus hasn't come.' embedded clause b. når Klaus ikke er kommet 1 2 3 4 5 when Klaus not is come ...'when Klaus hasn't come'

- Norwegian

(with multiple adverbials and multiple non-finite forms, in two varieties of the language)main

embeddedFront

—F vb

ConjSubj

SubjSentence adverb

Sentence adverb—

F vbN-f vb

N-f vbObj

ObjAdverbial

AdverbialKey: Subj=Subject

Obj=Object

Conj=Conjunction,

F vb= Finite verb

N-f vb = Non-finite verbmain clause a. Den gangen hadde han dessverre ikke villet sende sakspapirene før møtet. (Bokmål variety) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 this time had he unfortunately not wanted to send documents before the meeting ... 'This time he had unfortunately not wanted

to send the documents before the meeting.'embedded clause b. av di han denne gongen diverre ikkje hadde villa senda sakspapira føre møtet. (Nynorsk variety) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 because he this time unfortunately not had wanted to send documents before the meeting ... 'because this time he had unfortunately not wanted

to send the documents before the meeting.'

- Faroese

Unlike other continental Scandinavian languages, the sentence adverb may either precede or follow the finite verb in embedded clauses. A (3a) slot is inserted here for the following sentence adverb alternative.main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

SubjectS-adv

S-adv—

Finite verb—

S-advNon-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

AdverbialKey: S-adv=Sentence adverb main clause a. Her man fólk ongantíð hava fingið fisk fyrr 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 here must people never have caught fish before ... 'People have surely never caught fish here before.' embedded clause b. hóast fólk ongantíð hevur fingið fisk here 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 although people never have caught fish here c. hóast fólk hevur ongantíð fingið fisk here 1 2 4 (3a) 5 6 7 although people have never caught fish here ... 'although people have never caught fish here'

German, Dutch, Afrikaans

In these languages there is a strong tendency to place some or all of the verb forms in final position.

In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. As with other Germanic languages, the finite verb must be in the second position. However, any non-finite forms must be in final position. The subject may be in the first position, but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject follows the finite verb.

In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint does not hold. The finite verb form must be adjacent to any non-finite at the end of the clause, with different word-order in different languages.

German grammarians traditionally divide sentences into fields. Subordinate clauses preceding the main clause are said to be in the first field (Vorfeld), clauses following the main clause in the final field (Nachfeld).

The central field (Mittelfeld ) contains most or all of a clause, and is bounded by left bracket (Linke Satzklammer) and right bracket (Rechte Satzklammer) positions.

In main clauses, the initial element (subject or topical expression) is said to be located in the first field, the V2 finite verb form in the left bracket, and any non-finite verb forms in the right bracket.

In embedded clauses, the conjunction is said to be located in the left bracket, and the verb forms in the right bracket. In German embedded clauses, a finite verb form follows any non-finite forms.

- German[3]

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Main clause a. Er hat dich gestern nicht angerufen weil er dich nicht stören wollte. he has you yesterday not rung ... 'He didn't ring you yesterday because he didn't want to disturb you.' b. Sobald er Zeit hat wird er dich anrufen will he you ring ...'When he has time he will ring you.' Embedded clause c. dass er dich gestern nicht angerufen hat that he you yesterday not rung has ...'that he didn't ring you yesterday'

- Dutch[4]

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Main clause a. Tasman heeft Nieuw-Zeeland ontdekt Tasman has New Zealand discovered ...'Tasman discovered New Zealand.' b. In 1642 ontdekte Tasman Nieuw-Zeeland In 1642 discovered Tasman New Zealand ...'In 1642 Tasman discovered New Zealand.' c. Niemand had gedacht dat ook maar iets zou gebeuren. Nobody had thought ...'Nobody figured that anything would happen.' Embedded clause d. dat Tasman Nieuw-Zeeland ontdekt heeft that Tasman New Zealand discovered has ...'that Tasman discovered New Zealand'

This analysis suggests a close parallel between the V2 finite form in main clauses and the conjunctions in embedded clauses. Each is seen as an introduction to its clause-type, a function which some modern scholars have equated with the notion of specifier. The analysis is supported in spoken Dutch by the placement of clitic pronoun subjects. Forms such as ie cannot stand alone, unlike the full-form equivalent hij. The words to which they may be attached are those same introduction words: the V2 form in a main clause, or the conjunction in an embedded clause.[5]

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Main clause e. In 1642 ontdekte-n-ie Nieuw-Zeeland In 1642 discovered-(euphonic n)-he New Zealand ...'In 1642 he discovered New Zealand.' Embedded clause f. dat-ie in 1642 Nieuw-Zeeland ontdekt heeft that-he in 1642 New Zealand discovered has ...'that he discovered New Zealand in 1642'

Dutch differs from German in its word order in subordinate clause. In Dutch subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters and are referred to as the "red": omdat ik heb gewerkt, "because I have worked": like in English, where the auxiliary verb precedes the past particle, and the "green": omdat ik gewerkt heb, where the past particle precedes the auxiliary verb, "because I worked have": like in German.[6] In Dutch, the green word order is the most used in speech, and the red is the most used in writing, particularly in journalistic texts, but the green is also used in writing as is the red in speech. Unlike in English however adjectives and adverbs must precede the verb: ''dat het boek groen is'', "that the book is green"

First field Left bracket Central field Right bracket Final field Embedded clause g. omdat ik het dan gezien zou hebben most common in the Netherlands because I it then seen would have h. omdat ik het dan zou gezien hebben most common in Belgium because I it then would seen have i. omdat ik het dan zou hebben gezien often used in writing in both countries, but common in speech as well, most common in Limburg because I it then would have seen j. omdat ik het dan gezien hebben zou used in Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe, least common but used as well because I it then seen have would ...'because then I would have seen it'

Icelandic and Yiddish

These languages freely allow V2 order in embedded clauses.

- Icelandic

Two word-order patterns are largely similar to continental Scandinavian. However, in main clauses an extra slot is needed for when the front position is occupied by Það. In these clauses the subject follows any sentence adverbs. In embedded clauses, sentence adverbs follow the finite verb (an optional order in Faroese).[7]main clause

embedded clauseFront

—Finite verb

ConjunctionSubject

Subject—

Finite verbSentence adverb

Sentence adverbSubject

—Non-finite verb

Non-finite verbObject

ObjectAdverbial

Adverbialmain clause a. Margir höfðu aldrei lokið verkefninu. Many had never finished the assignment ... 'Many had never finished the assignment.' b. Það höfðu aldrei margir lokið verkefninu. there have never many finished the assignment ... 'There were never many people who had finished the assignment.' c. Bókina hefur María ekki lesið. the book has Mary not read ... 'Mary hasn't read the book.' embedded clause d. hvort María hefur ekki lesið bokina. whether Mary has not read the book ... 'whether Mary hasn't read the book'

In more radical contrast with other Germanic languages, a third pattern exists for embedded clauses with the conjunction followed by the V2 order: front-finite verb-subject.[8]

Conjunction

Front

(Topic adverbial)

Finite verb

Subject

e.

Jón

efast

um að

á morgun

fari

María

snemma

á fætur.

John

doubts

that

tomorrow

get

Mary

early

up

...

'John doubts that Mary will get up early tomorrow.'

Conjunction

Front

(Object)

Finite verb

Subject

f.

Jón

harmar

að

þessa bók

skuli

ég

hafa

lesið.

John

regrets

that

this book

shall

I

have

read

...

'John regrets that I have read this book.'

Yiddish

Unlike Standard German, Yiddish normally has verb forms before Objects (SVO order), and in embedded clauses has conjunction followed by V2 order.[9]

Front

(Subject)Finite verb Conjunction Front

(Subject)Finite verb a. ikh hob gezen mitvokh, az ikh vel nit kenen kumen donershtik I have seen Wednesday that I will not can come Thursday ... 'I saw on Wednesday that I wouldn't be able to come on Thursday.' Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject b. mitvokh hob ikh gezen, az donershtik vel ikh nit kenen kumen Wednesday have I seen that Thursday will I not can come ... On Wednesday I saw that on Thursday I wouldn't be able to come.'

Root clauses

One type of embedded clause with V2 following the conjunction is found throughout the Germanic languages, although it is more common in some than it is others. These are termed root clauses. They are declarative content clauses, the direct objects of so-called bridge verbs, which are understood to quote a statement. For that reason, they exhibit the V2 word order of the equivalent direct quotation.

- Danish

Items other than the subject are allowed to appear in front position.Conjunction Front

(Subject)Finite verb a. Vi ved at Bo ikke har læst denne bog We know that Bo not has read this book ... 'We know that Bo has not read this book.' Conjunction Front

(Object)Finite verb Subject b. Vi ved at denne bog har Bo ikke læst We know that this book has Bo not read ... 'We know that Bo has not read this book.'

- Swedish

Items other than the subject are occasionally allowed to appear in front position. Generally, the statement must be one with which the speaker agrees.Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject d. Jag tror att i det fallet har du rätt I think that in that respect have you right ... 'I think that in that respect you are right.'

This order is not possible with a statement with which the speaker does not agree.

Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject e. *Jag tror inte att i det fallet har du rätt (The asterisk signals that the sentence is not grammatically acceptable.) I think not that in that respect have you right ... 'I don't think that in that respect you are right.'

- Norwegian

Conjunction Front

(Adverbial)Finite verb Subject f. hun fortalte at til fødselsdagen hadde hun fått kunstbok (Bokmål variety) she told that for her birthday had' she received art-book ... 'She said that for her birthday she had been given a book on art.'

- German

Root clause V2 order is possible only when the conjunction dass is omitted.Conjunction Front

(Subject)Finite verb g. *Er behauptet, dass er hat es zur Post gebracht (The asterisk signals that the sentence is not grammatically acceptable.) h. Er behauptet, er hat es zur Post gebracht he claims (that) he has it to the post office taken ... 'He claims that he took it to the post office.'

Compare the normal embed-clause order after dass

Left bracket

(Conjunction)Central field Right bracket

(Verb forms)i. Er behauptet, dass er es zur Post gebracht hat he claims that he it to the post office taken has

V2 in English

Modern English differs greatly in word order from other modern Germanic languages, but earlier English shared many similarities. Some scholars therefore propose a description of Old English with V2 constraint as the norm. The history of English syntax is thus seen as a process of losing the constraint.[10]

Old English

In these examples, finite verb forms are in bold, non-finite verb forms are in italics and subjects are underlined.

Main clauses

- Subject first

a. Se mæssepreost sceal manum bodian þone soþan geleafan the masspriest must people preach the true faith .... 'The mass priest must preach the true faith to the people.'

- Question word first

b. Hwi wolde God swa lytles þinges him forwyrman Why would God so small thing him deny .... 'Why would God deny him such a small thing?'

- Topic phrase first

c. on twam þingum hæfde God þæs mannes sawle gedodod in two things had God the man's soul endowed .... 'With two things God had endowed man's soul.'

- þa first

c. þa wæs þæt folc þæs micclan welan ungemetlice brucende then was the people of-the great prosperity excessively partaking .... 'Then the people were partaking excessively of the great prosperity.'

- Negative word first

d. Ne sceal he naht unaliefedes don not shall he nothing unlawful do .... 'He shall not do anything unlawful.'

- Object first

e. Ðas ðreo ðing forgifð God his gecorenum these three things gives God his chosen .... 'These three things God gives to his chosen.'

Position of object

In examples b,c and d, the object of the clause precedes a non-finite verb form. Superficially, the structure is verb-subject-object- verb. To capture generalities, scholars of syntax and linguistic typology treat them as basically subject-object-verb (SOV) structure, modified by the V2 constraint. Thus Old English is classified, to some extent, as an SOV language. However, example a represents a number of Old English clauses with object following a non-finite verb form, with the superficial structure verb-subject-verb object. A more substantial number of clauses contain a single finite verb form followed by an object, superficially verb-subject-object. Again, a generalisation is captured by describing these as subject–verb–object (SVO) modified by V2. Thus Old English can be described as intermediate between SOV languages (like German and Dutch) and SVO languages (like Swedish and Icelandic).

Effect of subject pronouns

When the subject of a clause was a personal pronoun, V2 did not always operate.

f. forðon we sceolan mid ealle mod & mægene to Gode gecyrran therefore we must with all mind and power to God turn .... 'Therefore we must turn to God with all our mind and power.'

However, V2 verb-subject inversion occurred without exception after a question word or the negative ne, and with few exceptions after þa even with pronominal subjects.

g. for hwam noldest þu ðe sylfe me gecgyðan þæt... for what not-wanted you yourself me make-known that.. .... 'wherefore would you not want to make known to me yourself that...'

h. Ne sceal he naht unaliefedes don not shall he nothing unlawful do .... 'He shall not do anything unlawful.'

i. þa foron hie mid þrim scipum ut then sailed they with three ships out .... 'Then they sailed out with three ships.'

Inversion of a subject pronoun also occurred regularly after a direct quotation.[11]

j. "Me is," cwæð hēo, "Þīn cyme on miclum ðonce" to me is said she your coming in much thankfulness .... '"Your coming," she said, " is very gratifying to me".'

Embedded clauses

Embedded clauses with pronoun subjects were not subject to V2. Even with noun subjects, V2 inversion did not occur.

k. ... þa ða his leorningcnichtas hine axodon for hwæs synnum se man wurde swa blind acenned ... when his disciples him asked for whose sins the man became thus blind .... '... when his disciples asked him for whose sins the man was thus born blind'

Yes-No questions

In a similar clause pattern, the finite verb form of a yes-no question occupied the first position

l. Truwast ðu nu þe selfum and þinum geferum bet þonne ðam apostolum...? trust you now you self and your companions better than the apostles .... 'Do you now trust yourself and your companions better than the apostles...?'

Middle English

Continuity

Early Middle English generally preserved V2 structure in clauses with nominal subjects.

- Topic phrase first

a. On þis gær wolde þe king Stephne tæcen Rodbert in this year wanted the king Stephen seize Robert .... 'During this year king Stephen wanted to seize Robert.'

- Nu first

b. Nu loke euerich man toward himseluen now look every man to himself .... 'Now it's for every man to look to himself.'

As in Old English, V2 inversion did not apply to clauses with pronoun subjects.

- Topic phrase first

c. bi þis ȝe mahen seon ant witen... by this you may see and know

- Object first

d. alle ðese bebodes ic habbe ihealde fram childhade all these commandments I have kept from childhood

Change

Late Middle English texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show increasing incidence of clauses without the inversion associated with V2.

- Topic adverb first

e. sothely se ryghtwyse sekys þe Ioye and ... Truly the righteous seeks the joy and...

- Topic phrase first

f. And by þis same skyle hop and sore shulle jugen us And by this same skill hope and sorrow shall judge us

Negative clauses were no longer formed with ne (or na) as the first element. Inversion in negative clauses was attributable to other causes.

- Wh- question word first

g. why ordeyned God not such ordre why ordained God not such an order .... 'Why did God not ordain such an order?' (not follows noun phrase subject) h. why shulde he not .. Why should he not... (not precedes pronoun subject)

- There first

h. Ther nys nat oon kan war by other be there not-is not one can aware by other be .... 'There is not a single person who learns from the mistakes of others'

- Object first

h. He was despeyred; no thyng dorste he seye He was in despair; nothing dared he say

Vestiges of V2 in Modern English

As in earlier periods, Modern English normally has subject-verb order in declarative clauses and inverted verb-subject order[12] in interrogative clauses. However these norms are observed irrespective of the number of clause elements preceding the verb. Moreover, it is not useful to characterize the verb form which undergoes inversion as 'the finite verb'.

Classes of verbs in Modern English: auxiliary and lexical

Inversion in Old English sentences with a combination of two verbs could be described in terms of their finite and non-finite forms. The word which participated in inversion was the finite verb; the verb which retained its position relative to the Object was the non-finite verb. In most types of Modern English clause, there are two verb forms, but the verbs are considered to belong to different syntactic classes. The verbs which participated in inversion have evolved to form a class of auxiliary verbs which may mark tense, aspect and mood; the remaining majority of verbs with full semantic value are said to constitute the class of lexical verbs. The exceptional type of clause is that of declarative clause with a lexical verb in a Present simple or Past simple form.

Questions

Interrogative Wh- questions (like Yes/No questions) are regularly formed with inversion of subject and auxiliary. Present Simple and Present Past questions are formed with the auxiliary do, a process known as do-support.

a. Which games is Sam watching? b. Where does she live?

With topic adverbs and adverbial phrases

In certain patterns similar to Old and Middle English, inversion is possible. However, this is a matter of stylistic choice, unlike the constraint on interrogative clauses.

- negative or restrictive adverbial first

c. At no point will he drink Schnapps. d. No sooner had she arrived than she started to make demands.

- (see negative inversion)

- comparative adverb or adjective first

e. So keenly did the children miss their parents, they cried themselves to sleep. f. Such was their sadness, they could never enjoy going out.

After the preceding classes of adverbial, only auxiliary verbs, not lexical verbs, participate in inversion

- locative or temporal adverb first

g. Here comes the bus. h. Now is the hour when we must say goodbye.

- prepositional phrase first

i. Behind the goal sat many photographers. j. Down the road came the person we were waiting for.

After the two latter types of adverbial, only one-word lexical verb forms (Present Simple or Past Simple), not auxiliary verbs, participate in inversion, and only with noun-phrase subjects, not pronominal subjects.

Direct quotations

When the object of a verb is a verbatim quotation, it may precede the verb, with a result similar to Old English V2. Such clauses are found in storytelling and in news reports.

k. "Wolf! Wolf!" cried the boy. l. "The unrest is spreading throughout the country" writes our Jakarta correspondent.

- (see quotative inversion)

Declarative clauses without inversion

Corresponding to the above examples, the following clauses show the normal Modern English subject-verb order.

- Declarative equivalents

a'. Sam is watching the Cup games. b'. She lives in the country.

- Equivalents without topic fronting

c'. He will at no point drink Schnapps. d'. She had no sooner arrived than she started to make demands. e'. The children missed their parents so keenly that they cried themselves to sleep. g'. The bus is coming here. h'. The hour when we must say goodbye is now. i'. Many photographers sat behind the goal. j'. The person we were waiting for came down the road. k'. The boy cried "Wolf! Wolf!" l'. Our Jakarta correspondent writes, "The unrest is spreading throughout the country" .

V2 in Old French

Modern French is a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) language which is derived, like other Romance languages, from Latin, which is a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) language. However, there are more instances of V2 constructions in Old French than in other early Romance language texts. It has been suggested that this may be due to influence from the Germanic Frankish language.[13] The following sentences have been identified as possible examples of V2 syntax:[14]

a. Old French Longetemps fu ly roys Elinas en la montaigne Modern French Longtemps fut le roi Elinas dans la montagne .... 'Pendant longtemps le roi Elinas a été dans les montagnes.' English For a long time was the king Elinas in the mountain ... 'King Elinas was in the mountains for a long time.'

b. Old French Iteuses paroles distrent li frere de Lancelot Modern French Telles paroles dirent les frères de Lancelot .... 'Les frères de Lancelot ont dit ces paroles' English Such words uttered the brothers of Lancelot .... 'Lancelot's brothers spoke these words.'

c. Old French Atant regarda contreval la mer Modern French Alors regarda en bas la mer .... 'Alors Il a regardé la mer plus bas.' English Then looked at downward the sea .... 'Then he looked down at the sea.' (Elision of subject pronoun, contrary to the general rule in other Old French clause structures.)

Structural analysis

V2 behavior poses a problem for many theories of syntax. In particular, the set V2 position of the finite verb is difficult to accommodate if the theory acknowledges a finite verb phrase constituent. Chomskyan phrase structure grammars seek to overcome this difficulty by stipulating various movement procedures. For instance, if the theory assumes that all sentence structure is derived from SVO or SOV order, then one must posit two distinct instances of movement. By a fronting movement such as wh-movement or topicalization a constituent is moved to the left. By another fronting movement, the finite verb also moves to the left, but is blocked from moving further left than second position. According to this analysis, in embedded clauses, the presence of a complementizer (conjunction) may block a fronting movements in certain languages.[15]

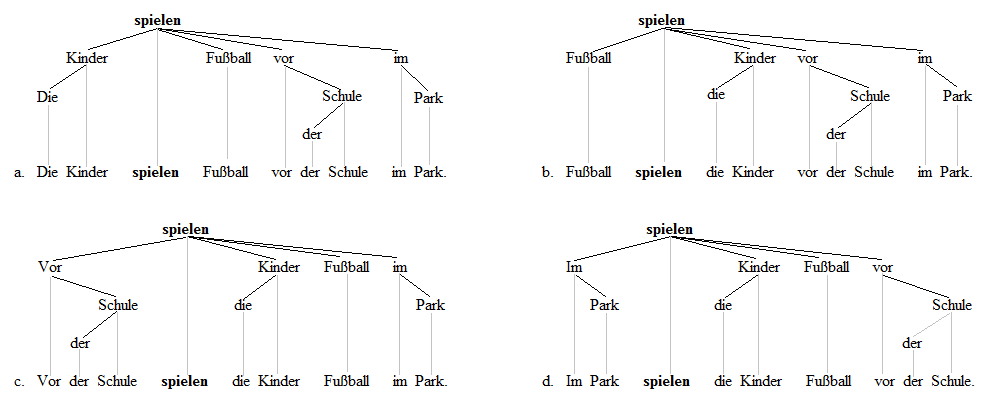

The V2 phenomenon is less problematic if a finite verb phrase is absent. In this respect, dependency grammar (DG), since it acknowledges no finite VP constituent, can accommodate the V2 phenomenon.[16] DG stipulates that one and only one constituent can be a predependent of the finite verb (i.e. a dependent which precedes its head) in declarative (matrix) clauses.[17] On this account, the V2 principle is violated if the finite verb has more than one predependent or no predependent at all. The following DG structures of the first four German sentences above illustrate the analysis (the sentence means 'The kids play soccer in the park before school'):

The finite verb spielen is the root of all clause structure. The V2 principle requires that this root have a single predependent, which it does in each of the four sentences.

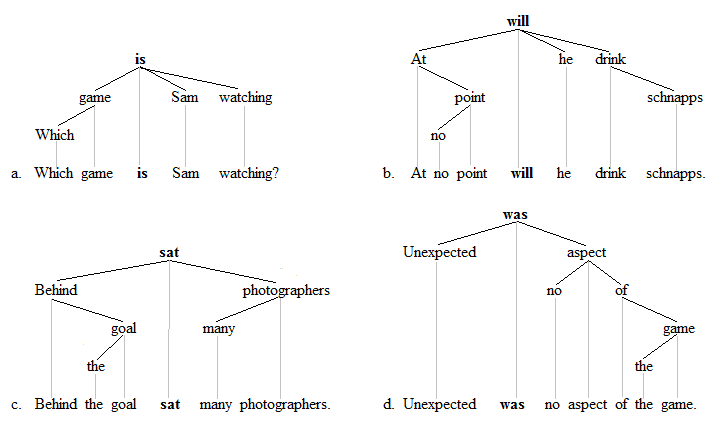

The four English sentences above involving the V2 phenomenon receive the following analyses:

X-bar theory analysis of V2

Another theoretical approach followed in recent treatments of Germanic syntax is X-bar theory. One aspect of this theory is the hierarchical division of the structure of a clause.

VP, IP and CP

- At the lowest level the VP (verb phrase) structure assigns position and functions to the elements of the proposition. This structure is shaped by the grammatical properties of the V (verb) which heads the structure.

- At a higher level, the IP (inflectional phrase) structure incorporates such grammatical features as tense and agreement, which may be necessary in a finite clause. The structure is shaped by the abstract I (inflection), which is considered the head of the structure.

- At the highest level the CP (complementizer phrase) structure incorporates the grammatical information which identifies the clause as declarative or interrogative, main or embedded. The structure is shaped by the abstract C (complementiser) which is considered the head of the structure. In embedded clauses the C position accommodates a subordinating conjunctions; in interrogative clauses it accommodates a question word or phrase. In declarative main clauses, C is basically unoccupied.

Verb position and movement

Fußball spielen

- The structure of non-finite clauses is VP with V as the head.

- In German and Dutch, the V head is to the right of other elements, yielding a verb-final word order.

(without subject)

spielten Fußball

- When finite properties are introduced, the clause acquires an IP structure with I as the head.

- This abstract collection of features merges with V, resulting in a finite-verb form which is no longer contained within the VP structure.

- Thus the verb is said to have moved from V to I.

- (The difference is more obvious in German and Dutch, less so in other languages.)

(with subject)

die Kinder spielten Fußball

- Another level of structure is necessary within the IP to admit the grammatical subject.

- Spec (specifier) is the term employed for the position of such an element at the start of a phrase.

- By this analysis the Subject phrase also moves from VP to IP.

- The grammatical properties of the V identify its subject within VP, but IP is the structure which admits agreement between subject and finite verb.

- When main vs subordinate (embedded) status is introduced, the clause acquires CP structure with C as the head.

- In main clauses, the C position is not, in principle, occupied by a lexical item.

Im Park spielten die Kinder Fußball

Fußball spielten die Kinder im Park

- In Germanic languages (except for English) the empty position often attracts the finite verb form away from its position as head of the IP.

- Thus the finite verb is said to have moved from I to C.

- Another layer of structure is necessary to admit an adverbial phrase.

- The element adjunct is distinct from specifier. More than one is allowed in a phrase and the position is more flexible.

- Thus the V2 structure is analysed as

- 1 Topic element (specifier of CP)

- 2 Finite-verb form (C=head of CP) i.e. verb-second

- 3 Remainder of the clause

- Thus the V2 structure is analysed as

daß die Kinder im Park Fußball spielten

- In embedded clauses, the C position is occupied by a conjunction.

- In most Germanic languages (but not in Icelandic or Yiddish), this generally prevents the finite verb from moving to C.

- In German and Dutch, the movement from V to I is reversed, resulting in so-called 'verb-final' order.

- The structure is analysed as

- 1 Conjunction (C=head of CP)

- 2 Subject (specifier of IP)

- 3 Bulk of clause (VP)

- 4 Finite verb (V position)

at denne bog har Bo ikke læst

- This analysis does not provide a structure for the instances in some language of root clauses after bridge verbs.

- Example: Danish Vi ved at denne bog har Bo ikke læst with the object of the embedded clause fronted.

- (Literally 'We know that this book has Bo not read')

- The solution is to allow verbs such as ved to accept a clause with a second (recursive) CP.

- The conjunction occupies C position in the upper CP.

- The finite verb moves to the C position in the lower CP.

Kashmiri

As was first noted in 1914 by Jules Bloch, V2 word order occurs outside of Germanic, in the Indo-Aryan language Kashmiri.[18] Declarative main clauses as well as embedded object clauses in Kashmiri have V2 word order, but relative clauses have SOV order, e.g.

- Basic sentence

- mye per yi kyitāb az.

- I read this book today.

- With fronted adverb

- az per mye yi kyitāb.

- Today read I this book.

- Subordinate clause

- mye von zyi mye per yi kyitāb az.

- I said that I read this book today.

- Subordinate clause with fronted adverb

- mye von zyi az per mye yi kyitāb.

- I said that today read I this book.

- Relative clause

- yi chi swa kyitāb ywas mye rāth per.

- This is the book I yesterday read.

- Relative clause with embedded subordinate clause

- yi chi swa kyitāb ywas mye az veny zyi mye per rāth.

- This is the book I today said that I read yesterday.

Kashmiri differs from the V2 languages of Europe in that in all clause types Kashmiri exhibits the characteristics of SOV languages. It has postpositions (not prepositions), objects before the main verb (not after - unless the main verb itself is in position 2), and auxiliaries after main verbs (unless the auxiliary itself is in position 2) [example from 'saaykal' by Ratan Lal Shant]:

- khaar oos rinyoomut Tyuub lemy-lemy Tayr-i manz-i nyebar keD-yith tshun-aan.

- mechanic was worn.out tube pulling-pulling tire-Abl inside-Abl out take.out-Ger THROW-ing

- 'The mechanic was pulling the worn-out tube out of the tire.'

The postposition manzi 'from inside' follows its object Tayri. The direct object Tyuub precedes its verb keD- 'take out'. The compound verb auxiliary tshun- THROW follows the main verb keD-.[19]

Kotgarhi and Kochi

In his 1976 three-volume study of two Indo-Aryan languages of Himachal Pradesh, Hendriksen reports on two intermediate cases: Kotgarhi and Kochi. Although neither language shows a regular V-2 pattern, they have evolved to the point that main and subordinate clauses differ in word order and auxiliaries may separate from other parts of the verb:

- hyunda-baassie jaa gõrmi hõ-i (Kotgarhi)

- winter-after GOES summer become-Gerund

- After winter comes summer. (Hendriksen III:186)

Hendriksen reports that relative clauses in Kochi show a greater tendency to have the finite verbal element in clause-final position than matrix clauses do (III:188).

Ingush

In Ingush, "for main clauses, other than episode-initial and other all-new ones, verb-second order is most common. The verb, or the finite part of a compound verb or analytic tense form (i.e. the light verb or the auxiliary), follows the first word or phrase in the clause." [20]

- muusaa vy hwuona telefon jettazh

- Musa V.PROG 2sg.DAT telephone striking

- 'Musa is telephoning you.'

O'odham

O'odham has relatively free word order within clauses; for example, all of the following sentences mean "the boy brands the pig":[21]

- ceoj ʼo g ko:jĭ ceposid

- ko:jĭ ʼo g ceoj ceposid

- ceoj ʼo ceposid g ko:jĭ

- ko:jĭ ʼo ceposid g ceoj

- ceposid ʼo g ceoj g ko:jĭ

- ceposid ʼo g ko:jĭ g ceoj

Despite the general freedom of sentence word order, O'odham is fairly strictly verb-second in its placement of the auxiliary verb (in the above sentences, it is ʼo; in the following it is ʼañ):

- Affirmative: cipkan ʼañ = "I am working"

- Negative: pi ʼañ cipkan = "I am not working" [not *pi cipkan ʼañ]

Sursilvan

Among dialects of the Romansh, V2 word order is limited to Sursilvan, the insertion of entire phrases between auxiliary verbs and participles occurs, as in 'Cun Mariano Tschuor ha Augustin Beeli discurriu ' ('Mariano Tschuor has spoken with Augustin Beeli'), as compared to Engadinese 'Cun Rudolf Gasser ha discurrü Gion Peider Mischol' ('Rudolf Gasser has spoken with Gion Peider Mischol'.)[22]

The constituent that is bounded by the auxiliary, ha, and the participle, discurriu, is known as a Satzklammer or 'verbal bracket'.

Notes

- ^ For discussions of the V2 principle, see Borsley (1996:220f.), Ouhalla (1994:284ff.), Fromkin et al. (2000:341ff.), Adger (2003:329ff.), Carnie (2007:281f.).

- ^ The examples are discussed in König and van der Auwera (1994) in the chapters devoted to each language.

- ^ These and other examples are discussed in Fagan (2009)

- ^ These and other examples are discussed in Zwart (2011)

- ^ Zwart (2011) p. 35.

- ^ http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_han001200701_01/_han001200701_01_0019.php

- ^ See Thráinsson (2007) p.19.

- ^ Examples from Fischer et al (2000) p.112

- ^ see König & van der Auwera (1994) p.410

- ^ See Fischer et al. (2000: 114ff.) for discussion of these and other examples from Old English and Middle English.

- ^ Harber (2007) p. 414

- ^ Inversion is discussed in Peters (2013)

- ^ see Rowlett (2007:4)

- ^ see Posner (1996:248)

- ^ For movement-type analyses of the V2 phenomenon, see for instance Emonds (1976:25), van Riemsdijk and Williams (1986:52), Ouhalla (1994:109ff.), Carnie (2007:281f.).

- ^ That DG denies the existence of a finite VP constituent is apparent with most any DG representation of sentence structure; finite VP is never shown as a complete subtree (=constituent). See for instance the trees in the essays on DG in Ágel et al. (2003/2006) in this regard. Concerning the strict denial of a finite VP constituent, see especially Tesnière (1959:103-105).

- ^ For an example of a DG analysis of the V2 principle, see Osborne (2005:260).

- ^ Jules Bloch, La formation de la langue marathe [The Formation of the Marathi Language], thesis, [1914/1920], Prix Volney.

- ^ Concerning Kashmiri as a V2 language, see Hook (1976: 133ff).

- ^ Nichols, Johanna. (2011). Ingush Grammar. Berkeley: The University of California Press. Pp. 678ff.

- ^ Zepeda, Ofelia. (1983). A Tohono O'odham Grammar. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

- ^ Liver 2009, pp. 138

Literature

- Adger, D. 2003. Core syntax: A minimalist approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Borsley, R. 1996. Modern phrase structure grammar. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Carnie, A. 2007. Syntax: A generative introduction, 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Emonds, J. 1976. A transformational approach to English syntax: Root, structure-preserving, and local transformations. New York: Academic Press.

- Fagan, S.M.B. 2009. German: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Fischer, O., A. van Kermenade, W. Koopman, and W. van der Wurff. 2000. The Syntax of Early English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fromkin, V. et al. 2000. Linguistics: An introduction to linguistic theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Harber, Wayne. 2007. The Germanic Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hook, P.E. 1976. Is Kashmiri an SVO Language? Indian Linguistics 37: 133-142.

- Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-58885-7

- König, E. and J. van der Auwera (eds.). 1994. The Germanic Languages. London and New York: Routledge.

- Liver, Ricarda. 2009. Deutsche Einflüsse im Bündnerromanischen. In Elmentaler, Michael (Hrsg.) Deutsch und seine Nachbarn. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Nichols, Johanna. 2011. Ingush Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Osborne T. 2005. Coherence: A dependency grammar analysis. SKY Journal of Linguistics 18, 223-286.

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

- Peters, P. 2013. The Cambridge Dictionary of English Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Posner, R. 1996. The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rowlett, P. 2007. The Syntax of French. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- van Riemsdijk, H. and E. Williams. 1986. Introduction to the theory of grammar. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Tesnière, L. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Thráinsson, H. 2007. The Syntax of Icelandic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zwart, J-W. 2011. The Syntax of Dutch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.