Vapor

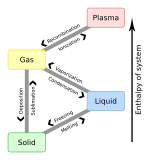

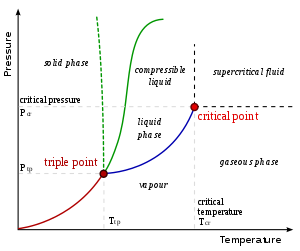

In physics a vapor (American) or vapour (British) is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical temperature,[1] which means that the vapor can be condensed to a liquid by increasing the pressure on it without reducing the temperature. A vapor is different from an aerosol.[2] An aerosol is a suspension of tiny particles of liquid, solid, or both within a gas.[2]

For example, water has a critical temperature of 374 °C (647 K), which is the highest temperature at which liquid water can exist. In the atmosphere at ordinary temperatures, therefore, gaseous water (known as water vapor) will condense into a liquid if its partial pressure is increased sufficiently.

A vapor may co-exist with a liquid (or a solid). When this is true, the two phases will be in equilibrium, and the gas-partial pressure will be equal to the equilibrium vapor pressure of the liquid (or solid).[1]

Properties

Vapor refers to a gas phase at a temperature where the same substance can also exist in the liquid or solid state, below the critical temperature of the substance. (For example, water has a critical temperature of 374 °C (647 K), which is the highest temperature at which liquid water can exist.) If the vapor is in contact with a liquid or solid phase, the two phases will be in a state of equilibrium. The term gas refers to a compressible fluid phase. Fixed gases are gases for which no liquid or solid can form at the temperature of the gas, such as air at typical ambient temperatures. A liquid or solid does not have to boil to release a vapor.

Vapor is responsible for the familiar processes of cloud formation and condensation. It is commonly employed to carry out the physical processes of distillation and headspace extraction from a liquid sample prior to gas chromatography.

The constituent molecules of a vapor possess vibrational, rotational, and translational motion. These motions are considered in the kinetic theory of gases.

Vapor pressure

The vapor pressure is the equilibrium pressure from a liquid or a solid at a specific temperature. The equilibrium vapor pressure of a liquid or solid is not affected by the amount of contact with the liquid or solid interface.

The normal boiling point of a liquid is the temperature at which the vapor pressure is equal to normal atmospheric pressure.[1]

For two-phase systems (e.g., two liquid phases), the vapor pressure of the individual phases are equal. In the absence of stronger inter-species attractions between like-like or like-unlike molecules, the vapor pressure follows Raoult's Law, which states that the partial pressure of each component is the product of the vapor pressure of the pure component and its mole fraction in the mixture. The total vapor pressure is the sum of the component partial pressures.[3]

Examples

- Perfumes contain chemicals that vaporize at different temperatures and at different rate in scent accords known as notes.

- Atmospheric water vapor is found near the earth's surface, and may condense into small liquid droplets and form meteorological phenomena such as fog, mist and haar.

- Mercury-vapor lamps and sodium vapor lamps produce light from atoms in excited states.

- Flammable liquids do not burn when ignited.[citation needed] It is the vapor cloud above the liquid that will burn if the vapor's concentration is between the lower flammable limit (LFL) and upper flammable limit (UFL) of the flammable liquid.

- E-Cigarettes allow users to inhale "e-liquid" aerosol/vapor, rather than cigarette smoke.[2]

Measuring vapor

Since it is in the gas phase, the amount of vapor present is quantified by the partial pressure of the gas. Also, vapors obey the barometric formula in a gravitational field just as conventional atmospheric gases do.

See also

References

- ^ a b c R. H. Petrucci, W. S. Harwood, and F. G. Herring, General Chemistry, Prentice-Hall, 8th ed. 2002, p. 483–86.

- ^ a b c Cheng, T. (2014). "Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii11–ii17. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995255. PMID 24732157.

- ^ Thomas Engel and Philip Reid, Physical Chemistry, Pearson Benjamin-Cummings, 2006, p.194