Wallachian uprising of 1821

| Wallachian uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Etaireía and Ottomans fighting in Bucharest (August 1821) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

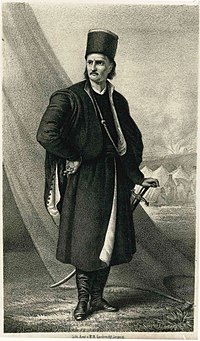

| Tudor Vladimirescu | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

8,000 (6,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry) 7+ cannons[1] | 15,000[2] | ||||||

The Wallachian uprising of 1821 was an uprising in Wallachia (a region of Romania) against Ottoman rule which took place during 1821.

Background

Prince Alexandru Suţu's death in January 1821 led to the forming of a temporary Comitet de Ocârmuire ("Governing Committee"), three regents - all of them members of the most representative indigenous boyar families, of which the most prominent was Caimacam Grigore Brâncoveanu. The Comitet, motivated against competition and denied Phanariote rulers' favours, decided to quickly manoeuver anti-boyar and anti-Phanariote sentiment in Wallachia (and especially in Oltenia), acting before the newly appointed Scarlat Callimachi could claim his throne. Therefore, an agreement between it and the Pandurs was reached on the 15th: Dimitrie Macedonski was awarded the post of lieutenant to Tudor.

The very same day, Vladimirescu sent a letter to the Ottoman Court of Mahmud II, stating that his objective was not the rejection of Ottoman rule, but that of the Phanariote regime, and showing his willingness for preservation of the traditional institutions. The statements were meant to buy Tudor time against Ottoman response, as he was already in negotiations with the Greek Anti-Ottoman revolutionary society Philikí Etaireía (having probably been in contact with it from around 1819). Together, they produced a plan for insurrection, with the two Eterist representatives (Giorgakis Olympios and Ioannis Pharmakis) assuring the Wallachians of Russian support for the common cause. It is apparent that Tudor was not himself a member of the Etaireía: the rigid command structure of the Brotherhood would have excluded the need for any negotiations.

Rebellion

After fortifying monasteries in Oltenia (Tismana, Strehaia) that were to serve him in the event of Ottoman intervention, Tudor travelled to Padeș where he issued his first proclamation (January 23). It included references to Enlightenment principles (notably, the right to resist oppression), but was also an almost millenarianist appeal to peasants, promising a "spring" to follow "winter".

In February, the demands were detailed by more documents. They included: the elimination of purchased offices in the administration, with the introduction of meritocratic promotion, the suppression of certain taxes and taxing criteria, the reduction of the main tax, the founding of a Wallachian Army, and an end to internal custom duties. In line with these, Tudor asked for the banishment of some Phanariote families and forbidding future Princes to hold a retinue that would compete with local boyars for offices. Calls by boyars in the Divan for Tudor to cease such activities (expressed by envoy Nicolae Văcărescu) were met with a virulent refusal.

The army, swelled up in numbers as it advanced, occupied Bucharest on March 21 - here, Tudor issued another important proclamation, one that expressed yet again his commitment to peace with the Ottomans. Previously, the Philikí Etaireía under Alexander Ypsilanti had emerged in Moldavia, proclaiming a liberation from Ottoman rule that was backed by the then Moldavian Prince Mihail Suţu (see Greek War of Independence). However, this coincided with Russian reaction against Greek rebellion, with the Russian army entering Moldavia and enforcing Holy Alliance policies. Ypsilanti's army headed south, reaching Pandur-occupied Bucharest.

End of the Uprising

Tudor's actions in the meanwhile had destroyed his alliance to local boyars. He had started wearing the kalpak (a tall, cylindrical, black leather hat; see Ottoman Clothing) reserved for the Prince, and demanded to be addressed as Domn ("Master", "Prince"; cf. Domnitor) - moving away from subordination to the landowners' cause.

The meeting between Ypsilanti and Tudor brought a new compromise. Tudor considered himself liberated from the provisions of the January agreement, as Russia was now an enemy of the Etaireía; Ypsilanti tried to persuade him that Russian support was still possible. The country was divided into a Greek administration and a Wallachian one, with Tudor's declaring himself neutral in face of large Ottoman armies preparing to cross the north of the Danube. Ottoman actions had been prompted by Russian threat of intervention in Wallachia.

Tudor's army retreated towards Oltenia in May, as the Ottomans occupied Bucharest without meeting resistance. Tudor was no longer capable of maintaining the discipline and cohesion of his own troops, and an attempt to ensure these through selective hangings only served to win him the fear of his subordinates. There was a general apathy when his willingness for a compromise with the Ottoman Empire caused him to be arrested (by the same Olimpiotul and Farmache, on June 1, in Goleşti), tried by the Etaireía, in Târgovişte. He was tortured, killed, and his mutilated body was thrown into a well near a monastery.[citation needed] The Etaireía did not succeed in its goal to assume command of Vladimirescu's army: most of it disbanded on the spot, with only a handful opposing Ottoman presence, and only up to August.