White House Farm murders

White House Farm in 2007 | |

| Date | 6 – 7 August 1985 |

|---|---|

| Location | White House Farm, near Tolleshunt D'Arcy, Essex, England |

| Coordinates | 51°45′33″N 0°48′12″E / 51.7591°N 0.8032°E |

| Deaths |

|

| Convicted | Jeremy Bamber (then 24), convicted on 28 October 1986 of five counts of murder |

| Sentence | Whole-life order |

The White House Farm murders took place near the village of Tolleshunt D'Arcy, Essex, England, during the night of 6 – 7 August 1985. Nevill and June Bamber were shot and killed inside their farmhouse, along with their adoptive daughter, Sheila Caffell, and Sheila's six-year-old twin sons. The only surviving member of the immediate family was June and Nevill's adoptive son, Jeremy Bamber, then 24 years old, who said he had been at home a few miles away when the shooting took place.[1]

The police at first believed that Sheila, diagnosed with schizophrenia, had fired the shots then turned the gun on herself. But weeks after the murders Jeremy Bamber's ex-girlfriend told police that he had implicated himself. The prosecution argued that, motivated by a large inheritance, Bamber had shot the family with his father's semi-automatic rifle, then placed the gun in his unstable sister's hands to make it look like a murder–suicide. A silencer the prosecution said was on the rifle would have made it too long, they argued, for Sheila's fingers to reach the trigger to shoot herself. Bamber was convicted of five counts of murder in October 1986 by a 10–2 majority, sentenced to a minimum of 25 years, and informed in 1994 that he would never be released.[2][3]

Bamber protested his innocence throughout, although his extended family remained convinced of his guilt.[4] Between 2004 and 2012 his lawyers submitted several unsuccessful applications to the Criminal Cases Review Commission.[5] They argued that the silencer might not have been used during the killings, that the crime scene may have been damaged then reconstructed, that crime-scene photographs were taken weeks after the murders, and that the time of Sheila's death was miscalculated.[6][7]

A key issue was whether Bamber received a call from his father that night to say Sheila had "gone berserk" with a gun. Bamber said that he did, that he alerted police, and that Sheila fired the final shot while he and the officers were standing outside the house. It became a central plank of the prosecution's case that the father had made no such call, and that the only reason Bamber would have lied about it—indeed, the only way he could have known about the shootings when he alerted the police—was that he was the killer himself.[8]

Bambers

Nevill and June Bamber

Ralph Nevill Bamber (known as Nevill, born 8 June 1924, 61 when he died), was a farmer, former RAF pilot, and local magistrate at Witham Magistrates' Court. He and his wife, June (née Speakman, born 3 June 1924, also 61 when she died), had married in 1949 and moved into the Georgian White House Farm on Pages Lane, Tolleshunt D'Arcy, set among 300 acres of tenant farmland that had belonged to June's father.[9][10] Nevill was described in court as 6' 4" tall and in good physical health, a point that became significant because Bamber's defence was that Sheila, a slim woman of 28, was able to beat and subdue her father, something the prosecution contested.[11]

Unable to have biological children, the couple adopted Sheila and Jeremy as babies; the children were not related to one another. The Bambers were wealthy and gave the children a good home and private education, but June was intensely religious and reportedly tried to force her children and grandchildren to adopt the same ideas. She had a poor relationship with Sheila, who felt June disapproved of her, and June's relationship with Jeremy was so troubled that he had apparently stopped speaking to her. The court heard that Sheila's ex-husband was concerned about the effect June was having on his sons; she apparently made them kneel and pray with her, which upset him. She suffered from depression and in 1982 was treated by the psychiatrist who later saw Sheila.[12][13]

Sheila Caffell

Background

Sheila Jean Caffell (born 18 July 1957, 28 when she died)[14] was born to the 18-year-old daughter of a senior chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Her biological mother named her Phyliss, and gave her up to the Church of England Children's Society two weeks after the birth, at the insistence of the chaplain. In October that year Phyliss was adopted by the Bambers and renamed Sheila.[15] She attended private schools, first Moira House in Eastbourne, Sussex, then Old Hall School in Hethersett, Norfolk, followed by secretarial college in Swiss Cottage, London.[16] In 1974, when she was 17, Sheila discovered she was pregnant by her boyfriend, Colin Caffell (later her husband); the Bambers arranged an abortion. Her relationship with her adoptive mother deteriorated significantly that summer, when June found Sheila and Colin sunbathing naked in a field. June reportedly started calling Sheila the "devil's child," which the psychiatrist identified as the trigger for Sheila's paranoid delusions about having been taken over by the devil.[17]

Sheila continued with her secretarial course, then trained as a hairdresser, and briefly found work as a model with the Lucie Clayton agency, which included two months' work in Tokyo. She and Colin married in May 1977 when Sheila was 20. She suffered two more miscarriages, then on 22 June 1979 the twins were born.[18] The birth led to a deterioration in her mental health. She became increasingly erratic, throwing pots and pans at her husband, and once pushing her hands through a window, cutting herself. The couple separated just four months after the birth, and divorced in May 1982.[19]

After the breakdown of the marriage, Nevill bought Sheila a flat in Morshead Mansions, Maida Vale, London, and Colin continued to help raise the children from his home in nearby Kilburn. Sheila became friendly with a group of young women who nicknamed her "Bambi," and who later told reporters that she was vulnerable and desperately insecure, often complaining about her poor relationship with her adoptive mother. One said there was a lot of partying and drugs, particularly cocaine, and older men who were interested in the women for all the wrong reasons.[20] Sheila's brief modelling career ended after the birth of the boys, and she lived on welfare or took low-paying jobs, including as a waitress at School Dinners, a London restaurant in which a traditional British menu is served up by young women in stockings and suspenders. There were also cleaning jobs, and there was one episode of nude photography, much regretted.[21]

Mental health

Sheila's mental health continued to decline, with episodes of banging her head against walls and becoming agitated to the point where one of her boyfriends feared for his safety.[22] She decided to trace her birth mother, then living in Canada, and with the help of social services they met at Heathrow Airport in 1982 for a brief reunion, but it seems the relationship did not develop.[23] The boys were briefly placed in foster care in 1982 and 1983, an arrangement that seemed to cause no problems.[24]

In August 1983 Sheila was referred by her family doctor to Dr. Hugh Ferguson, the psychiatrist who had earlier treated June. He said she was in an agitated, paranoid and psychotic state; he admitted her to St Andrew's Hospital in Northampton, where she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder.[25]

Ferguson wrote that Sheila believed the devil had given her the power to project evil onto others, and that she could make her sons have sex and cause violence with her. She called them the "devil's children," the phrase June had apparently used of Sheila, and said she believed she was capable of murdering them or of getting them to kill others. She spoke about suicide, though the court heard that Ferguson did not regard her as a suicide risk. She was discharged on 10 September 1983.[25] Ferguson continued treating her as an outpatient; he diagnosed schizophrenia and prescribed trifluoperazine, an antipsychotic drug.[26]

In 1985 Sheila became more enthusiastic about religion, to the surprise of her friends who were apparently unaware that she came from a religious family.[27] She was re-admitted to St Andrew's in March 1985, five months before the murders, believing her boyfriend at the time to be the devil and herself to be in direct communication with God.[28] She was discharged just under four weeks later, and as an outpatient received a monthly injection of haloperidol, an antipsychotic drug that has a sedative effect.[29]

She went to stay at White House Farm to recuperate. It was obvious to her friends and family that her mental health was getting worse.[27] Just before the murders, Colin complained that he was doing 95 percent of the work with the boys; he drafted a letter to Sheila's father in late March or early April 1985, which was never sent, asking him to persuade Sheila to let the twins live with Colin most of the time.[30] According to Bamber, the family discussed placing the boys in daytime foster care over dinner on the night of the murders, with little response from Sheila.[31]

Despite Sheila's erratic mental state, her psychiatrist told the court that the kind of violence necessary to commit the murders was not consistent with his view of her. In particular, he said he did not believe she would have killed her father or children, because her difficult relationship was confined to her mother.[32] Her ex-husband said the same: that, despite her tendency to throw things and sometimes hit him, she had never harmed the children.[33] June Bamber's sister, Pamela Boutflour, testified that Sheila was not a violent person and that she had never known Sheila to use a gun; June's niece, Ann Eaton, told the court that Sheila did not know how to use one.[34] Bamber disputed this, telling police on the night of the shooting, as they stood outside the house, that he and Sheila had gone target shooting together. He acknowledged later that he had not seen her fire a gun as an adult.[35]

Jeremy Bamber

Jeremy Nevill Bamber (born 13 January 1961) is the son of a student midwife who, after an affair with a married army sergeant, gave her baby to the Church of England Children's Society when he was six weeks old. His biological parents later married each other and had other children.[37]

Nevill and June adopted Bamber when he was six months old. They sent him to private schools, first to Maldon Court, a preparatory school, then to Gresham's School, a boarding school in Holt, Norfolk. He left Gresham's with no qualifications, but attended sixth-form college and in 1978 passed seven O-levels.[38] Nevill paid for him to visit Australia, where Bamber took a scuba diving course, then New Zealand. Former friends alleged that he had broken into a jeweller's shop while in New Zealand and had stolen an expensive watch, and had also boasted, they said, of being involved in smuggling heroin.[39]

He returned to England to work on his adoptive parents' farm for £170 a week,[1] and set up home rent-free in a cottage Nevill owned at 9 Head Street, Goldhanger (51.745857°N 0.755881°E). The cottage lay 3–3.5 miles (5.6 km) from the farmhouse (51.7591°N 0.8032°E), a five-minute drive by car and at least 15 minutes by bicycle. [40] His father also gave him a car to use, and Jeremy owned eight percent of a family company, Osea Road Camp Sites Ltd, which ran a caravan site.[41]

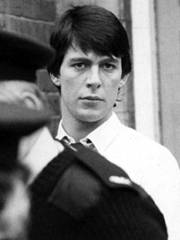

To Bamber's supporters, who over the years have included several MPs and journalists, he is the victim of Britain's most serious miscarriage of justice.[42] The Guardian took up his case at one point; two Guardian journalists who interviewed him in 2011 called him "clever and strategic." They wrote that there was something about him that made the public unsympathetic toward him: he was "handsome in a rather cruel, caddish way—he seemed to exude arrogance and indifference. ... Like Meursault in the Camus novel L'Etranger, he did not seem to display the appropriate emotions."[43]

His detractors, a group that includes his extended family, see him as a psychopath, and regard his long fight to have the conviction declared unsafe as part of the clinical picture.[44] His father's secretary, Barbara Wilson, told a documentary in November 2013 that Bamber used to provoke his parents, riding in circles around his mother on a bicycle, wearing make-up in public to upset his father, and allegedly once hiding a bag of live rats in his mother's car. She said that Bamber's father did not trust him, and that whenever Bamber visited the farmhouse there were arguments. Tension had increased in the weeks before the murders; she said Bamber's father had mentioned something to her about foreseeing a "shooting accident."[45] Bamber underwent several assessments in prison, and according to the Guardian no indication of mental illness or psychopathy was found.[43] He passed a lie detector test in 2007.[46]

Extended family, inheritance

The financial ties and inheritance issues within the immediate and extended family added a layer of complexity to the case. The prosecution argued that Bamber had killed his family to inherit £436,000, the farmhouse where the murders took place, 300 acres (1.2 km2) of land, and the caravan site in Maldon. Because of his conviction, the estate passed instead to the cousins who had found the silencer in the gun cupboard after the murders, with the flecks of blood and paint that proved pivotal to the prosecution's case.[47]

After Bamber's conviction, one cousin on his mother's side moved into White House Farm, and that cousin and several others acquired ownership of the caravan site.[48] Bamber argues that they set him up, a claim another cousin dismissed in 2010 as "an absolute load of piffle."[47] Bamber launched two legal actions to secure a share of the estate, which the cousins said in 2004 was part of an attempt to harass and vilify them.[49]

Murder weapon

Nevill kept several guns at the farm. He was reportedly careful with them, cleaning them after use and securing them.[50] The murder weapon was a .22 Anschütz semi-automatic rifle, model 525, which Nevill purchased on 30 November 1984, along with a Parker Hale sound moderator (a "silencer"), telescopic sights, and 500 rounds of ammunition. The rifle used cartridges, which were loaded into a magazine that held ten cartridges. Twenty-five shots were fired during the killing, so assuming it was fully loaded to begin with, it would have been reloaded at least twice. The court heard that the gun became progressively harder to load as the number of cartridges increased; loading the tenth was described as exceptionally hard.[51]

The rifle had normally been used, with the silencer and telescopic sights attached, to shoot rabbits. The court heard that a screwdriver was needed to remove the sights, but they were usually left in place because it was time-consuming to realign them. Nevill's nephew, Anthony Pargeter, visited the farmhouse around 26 July 1985, and told the court that he had seen the rifle, with the sights and silencer attached, in the gun cupboard in the ground-floor office. Bamber testified that he had visited the farmhouse on the evening of 6 August, hours before the murders, and that he had loaded the gun, thinking he heard rabbits outside, then left it with a full magazine and a box of ammunition on the kitchen table.[51]

White House Farm, 6–7 August 1985

Sheila's visit

On 4 August 1985, three days before the murders, Sheila and the boys arrived at her parents' home at White House Farm to spend the week with them. The housekeeper saw her that day and noticed nothing unusual. Sheila was seen the next day with her children by two farm workers, Julie and Leonard Foakes, who said she seemed happy.[52] One of the crime-scene photographs shows that someone, possibly Sheila, had carved "I hate this place" into the cupboard doors of the bedroom the twins were sleeping in.[53]

Bamber visited the farm on the evening of Tuesday, 6 August. He told the court that his parents suggested to Sheila that evening that the boys be placed in day-time foster care with a local family, because of her mental-health problems. Bamber said Sheila did not seem bothered by the suggestion and had simply said she would rather stay in London.[31] The boys had been in foster care before, although in London rather than near White House Farm, and it had not appeared to cause a problem for Sheila. Her psychiatrist, Dr. Ferguson, told the Court of Appeal in 2002 that any suggestion that the children be removed from her care would have provoked a strong reaction from Sheila, but that she might have welcomed daytime help.[54]

Barbara Wilson, the farm's secretary, telephoned the farmhouse at 9.30 pm that evening and spoke to Nevill. She said he was short with her, and Wilson was left with the impression that she had interrupted an argument. June Bamber's sister, Pamela Boutflour, also telephoned that evening at about 10 pm. She spoke to Sheila, who she said was quiet, then to June, who seemed normal.[55]

Telephone calls

There was one telephone line and normally four telephones at the farm: a cordless phone with a memory-recall feature in the kitchen; a beige digital phone, also kept in the kitchen; a blue digital phone in the first-floor office; and a cream rotary phone (dial phone) in the main bedroom. The cordless phone had been sent away for repair on 5 August, so on the night of the murders there were three phones in the house.[56]

The rotary phone that was normally in the main bedroom had been moved into the kitchen where the beige digital phone normally sat. Police found the latter under a pile of magazines. They found the rotary phone in the kitchen with its receiver off the hook. The implication was that someone—Nevill, according to Bamber—had been interrupted mid-call.[56]

A central issue is whether Nevill telephoned Bamber before the murders to say that Sheila had gone crazy with a gun. Bamber said he did receive such a call, and that the line went dead in the middle of it, which was consistent with the phone being found off the hook. The prosecution said that he had not received such a call, and that his claim to have done so was part of his setting the scene to blame Sheila; it was Bamber himself, they said, who had left the phone off the hook. This was one of three key points the jury was asked to consider by the trial judge during his summing up.[8] In 2010 Bamber's lawyers highlighted two police phone logs (below) in support of Bamber's application to have his case referred back to the Court of Appeal. The question was whether these logs described one call to the police, from Bamber alone, or two calls, one from Bamber and another from his father.[57]

Telephone log 1

A police log timed at 3:26 am on 7 August 1985 (right) was entered as evidence at the trial but not shown to the jury. It discusses a telephone call made that night to a local police station. According to the prosecution, the log discusses a call known to have been made by Bamber. According to Bamber's defence team, it may show that a separate call was made by Nevill.[57]

The log is headed "Daughter gone berserk": "Mr Bamber, White House Farm, Tolleshunt d’Arcy—daughter Sheila Bamber, aged 26 years, has got hold of one of my guns." It adds: "Message passed to CD by the son of Mr Bamber after phone went dead." It goes on to say: "Mr Bamber has a collection of shotguns and .410s," and it includes the telephone number 860209, the number at the time for White House Farm. The final entry says: "0356 GPO [the telephone operator] have checked phone line to farmhouse and confirm phone left off hook." The log shows that a patrol car, Charlie Alpha 7 (CA7), was sent to the scene at 3.35 am.[57]

Telephone log 2

A different police log shows that, at 3.36 am, Bamber rang Chelmsford Police Station using a direct line, rather than the emergency number (999), and spoke to PC West. The court accepted that the officer who recorded the log misread a digital clock, and that the call had probably come in at around 3:26 am, around the time of the call mentioned in the first log.[58]

Bamber said: "You've got to help me. My father has just rung me and said, 'Please come over. Your sister has gone crazy and has got the gun.' Then the line went dead." Bamber said he had tried to ring his father back, but there was no reply.[58] The log continues: "Father Mr. Bamber, White House Farm, Tolleshunt D'Arcy ... Sister Sheila Bamber age 27. Has history of mental illness. ... Dispatched CA5 [Charlie Alpha 5] to scene ... Informant requested to attend scene."[57]

Police response

PC West contacted civilian dispatcher Malcolm Bonnet at the Chelmsford HQ Information Room using a radio link; this conversation was recorded as having taken place at 3.26 am. PC West then spoke to Bamber again, who apparently complained about the time the police response was taking, and said: "When my father rang he sounded terrified." He was told to go to the farm and wait for the police. At 3.35 am Bonnet sent a police car to White House Farm. A telephone operator checked the line to the farm at 03:56, according to a police log, or at 04:30, according to the Court of Appeal. The phone was off the hook, the line was open and a dog could be heard barking.[58]

Explaining why he had called a local police station and not 999, Bamber told police that night that he had not thought it would make a difference in terms of how fast they arrived.[59] He said he had spent time looking up the number, and even though his father had asked him to come quickly, he had first telephoned his girlfriend, Julie Mugford, in London, then had driven slowly to the farmhouse. He also said he could have called one of the farm workers, but had not at the time considered it.[60] In his early witness statements, Bamber said he had telephoned the police immediately after receiving his father's call, then telephoned Mugford. During later police interviews, he said he had called Mugford first. He said he was confused about the sequence of events.[59]

Scene outside

After the telephone calls, Bamber made his way to the farmhouse, as did PS Bews, PC Myall and PC Saxby from Witham Police Station, passing Bamber in their car on the way there. They told the court that, in their view, he was driving much slower than them. Bamber's cousin, Ann Eaton, testified that Bamber was normally a fast driver.[61][62]

Bamber arrived at the farmhouse one or two minutes after the police. They waited for a tactical firearms group to arrive, which turned up at 5 am and decided to wait until daylight before trying to enter. Police determined that all the doors and windows to the house were shut, except for the window in the main bedroom on the first floor. Using a loudhailer, they spent two hours trying to communicate with Sheila. The only sound they reported from the house was a dog barking.[61][63]

While waiting outside, the police questioned Bamber, who they said seemed calm. He told them about the phone call from his father, and that it sounded as though someone had cut him off. He said he did not get along with his sister. When asked whether she might have gone berserk with the gun, the police said he replied: "I don't really know. She is a nutter. She's been having treatment." The police asked why Nevill would have called Bamber and not the police. Bamber replied that his father was the sort of person who might want to keep things within the family.[64]

Bamber told the police that Sheila was familiar with guns and that they had gone target shooting together. He said he had been at the farmhouse himself a few hours earlier, and that he had loaded the rifle because he thought he had heard rabbits outside. He had left it on the kitchen table fully loaded, with a box of ammunition nearby.[65] After the bodies were discovered, a doctor, Dr. Craig, was called to the house to certify the deaths, which he testified could have occurred at any time during the night. He said Bamber appeared to be in a state of shock; he broke down, cried and seemed to vomit. The doctor said Bamber told him at that point about the discussion the family had had about possibly having Sheila's sons placed in foster care.[66]

Inside farmhouse

Nevill

The police eventually entered at 7:54 am through the back door, which had been locked from the inside.[61] They found five bodies with multiple gunshot wounds. Twenty-five shots had been fired, mostly at close range.[67] Nevill was found downstairs in the kitchen, dressed in pyjamas, lying over an overturned chair next to the fireplace, amid a scene suggestive of a struggle.[68] A telephone was lying on one of the kitchen surfaces with its receiver off the hook, next to several .22 shells. The police said chairs and stools were overturned, and there was broken crockery, a broken sugar basin, and what looked like blood on the floor. A ceiling light lampshade had been broken.[69]

Nevill had been shot eight times, six times to the head and face, fired when the rifle was a few inches from his skin. The remaining shots to his body had occurred from at least two feet away. Based on where the empty cartridges were found—three were in the kitchen and one on the stairs—the police concluded he had been shot four times upstairs, but had managed to get downstairs where a struggle took place, during which he was hit several times with the rifle and shot again, this time fatally.[70]

There were two wounds to his right side, and two to the top of his head, which would probably have resulted in unconsciousness. The left side of his lip was wounded, his jaw was fractured, and his teeth, neck and larynx were damaged. The pathologist said he would have had difficulty speaking. There were gunshot wounds to his left shoulder and left elbow. He also had black eyes, a broken nose, bruising to the cheeks, cuts on the head, bruising to the right forearm, and circular burn-type marks on his back, consistent with his having been hit with the rifle.[70] One of the pillars of the prosecution case was that Sheila would not have been strong enough to inflict this beating on Nevill, who was 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) tall and by all accounts in good health.[1]

June

The court heard that the other four bodies were found upstairs. June's body was heavily bloodstained. She was found lying on the floor in the master bedroom by the doorway, bare-footed and wearing her nightdress. She had been shot seven times; one shot to her forehead between her eyes, and another to the right side of her head, would have caused her death quickly. There were also shots to the right side of her lower neck, her right forearm, and two injuries on the right side of her chest and her right knee. The police believed she had been sitting up during part of the attack, based on the pattern of blood on her clothing. Five of the shots occurred when the gun was at least a foot from her body. The shot between her eyes was from less than one foot.[71]

Daniel and Nicholas

The boys were found in their beds, shot through the head. They appeared to have been shot while in bed. Daniel had been shot five times in the back of the head, four times with the gun held within one foot of his head, and once from over two feet away. Nicholas had been shot three times, all contact or close-proximity shots.[72]

Sheila

The court heard that Sheila was found on the floor of the master bedroom with her mother. She was in her nightdress and bare-footed, with two bullet wounds under her chin, one on her throat. The pathologist, Dr Peter Vanezis, said that the lower of the injuries had occurred from three inches (76 mm) away, and that the higher one was a contact injury. The higher of the two would have killed her immediately. The lower injury would have killed her too, he said, but not necessarily straightaway. Vanezis testified that it would be possible for a person with such an injury to stand up and walk around, but the lack of blood on her nightdress suggested to him that she had not done this. He believed that the lower of her injuries had happened first, because it had caused bleeding inside the neck; the court heard that if the immediately fatal wound had had happened first, the bleeding would not have occurred to the same extent. Vanesiz said that the pattern of blood stains on her nightdress suggested she had been sitting up when she received both injuries.[73]

There were no marks on her body suggestive of a struggle. The firearms officer who first saw her said her feet and hands were clean, her fingernails manicured and not broken, and her fingertips free of blood, dirt or powder. There was no trace of lead dust. The rifle magazine would have been loaded at least twice during the killings; this would usually leave lubricant and material from the bullets on the hands. A scenes-of-crimes officer, DC Hammersley, said there were bloodstains on the back of her right hand, but that otherwise her hands were clean.[73]

There was no blood on her feet or other debris, such as the sugar that was on the downstairs floor. Low traces of lead were found on her hands and forehead at postmortem, but the levels were consistent with the everyday handling of things around the house. A scientist, Mr Elliott, testified that if she had loaded 18 cartridges into a magazine he would expect to see more lead on her hands. The blood on her nightdress was consistent with her own, and no trace of firearm-discharge residue was on it. Blood and urine samples indicated that she had taken the anti-psychotic drug haloperidol, and several days earlier had used cannabis.[73]

The rifle, without the silencer or sights attached, was lying on her body pointing up at her neck. June's Bible lay on the floor to the right of Sheila. It was normally kept in a bedside cupboard. June's fingerprints were on it, as were others that could not be identified, including one made by a child.[74]

Police investigation

Criticism

Journalist David Connett, who attended the trial, writes that it was by common consent a poor investigation.[75] The trial judge, Mr Justice Drake, expressed concern about what he called a "less than thorough investigation."[76] According to Claire Powell, "doing a Bamber" briefly became police slang for making a mess of a case.[77]

According to Connett, the officer in charge, DCI "Taff" Jones, deputy head of CID, was told that it was a "domestic," and went off to play golf. Jones became so convinced of the murder–suicide theory that he ordered Bamber's cousins out of his office when they asked him to consider whether Bamber had set the whole thing up. Evidence was not recorded or preserved, and three days after the killings the police burned bloodstained bedding and a carpet, apparently to spare Bamber's feelings. The inquest opened on 14 August 1985, and the police gave evidence that it was a murder–suicide.[75]

The scenes-of-crime officer did not find the silencer in the cupboard. It was found by one of Bamber's cousins days later, and it took the police three days to collect it from them. The same officer moved the rifle without wearing gloves, and it was not examined for fingerprints until weeks later. The Bible found with Sheila was not examined at all. Connett writes that a hacksaw blade that might have been used to gain entry to the house lay in the garden for months. Officers did not take contemporaneous notes; those who had dealt with Bamber wrote down their statements weeks later. Bamber's clothes were not examined until one month later. The bodies were cremated. Ten years later all blood samples were destroyed.[75]

Unlike DCI Jones, his junior officers were suspicious of Bamber, and when Jones was removed from the case, they began to look more closely at him. (Jones died before the case came to court after falling from a ladder at his home.) Bamber's behaviour after the funeral increased suspicion that he had been involved. The Times reported that, immediately after the bodies were found, he broke down and was offered tea and whisky by police, and apparently managed to persuade them to burn bedding and carpets inside the house. He wept openly at the funerals, supported by his girlfriend, Julie Mugford, after which he flew to Amsterdam, where he apparently tried to buy a consignment of drugs and offered to sell nude photographs of Sheila to tabloid newspapers. He also invited friends to expensive champagne-and-lobster dinners. His behaviour served to draw police attention to him.[1]

Fingerprints on rifle

A print from Sheila's right ring finger was found on the right side of the butt, pointing downwards. A print from Bamber's right forefinger was on the rear end of the barrel, above the stock and pointing across the gun. He said he had used the gun to shoot rabbits. There were three other prints that could not be identified.[78]

Silencer

On the day of the murders, the police searched the gun cupboard in the ground-floor office, but did not examine it closely or search for the silencer or sights for the rifle. Three days later, members of Bamber's extended family visited the farm with Basil Cock, the estate's executor. During that visit one of Bamber's cousins, David Boutflour, found the silencer and sights in the cupboard. The court heard that several people had witnessed this discovery: Boutflour's father and sister; the farm secretary; and Basil Cock. The family took the silencer to Boutflour's sister's home to examine it. They said they found the surface of it had been damaged and that there seemed to be red paint and blood on it. They told the police about their find, and the police collected the silencer from them on 12 August, five days after the murders. At that point the police reportedly noticed an inch-long grey hair attached to the silencer, but this was lost before the silencer arrived at the Forensic Science Service at Huntingdon.[79]

The family returned to the farmhouse to search for the source of the red paint, and found what they said was recent damage to the underside of the red-painted mantelpiece above the Aga cooker in the kitchen. A scenes-of-crime officer, DI Cook, took a paint sample from the mantelpiece on 14 August, and it contained the same 15 layers of paint and varnish that were in the paint flake on the silencer. On 1 October casts were taken of the marks on the mantel, and the marks were deemed consistent with the silencer having come into contact with the mantelpiece more than once.[79] In February 2010 Bamber's legal team submitted evidence that they said showed the marks had been created after the crime-scene photographs were taken (see below).[80]

A scientist at the Forensic Science Laboratory, Mr. Hayward, found blood on the inside and outside surface of the silencer, the latter not enough to permit analysis. The blood inside was found to be the same blood group as Sheila's, although it might have been a mixture of Nevill's and June's. A firearms expert, a Mr. Fletcher, said the blood was backspatter, caused by a close-contact shooting. Tests at the lab indicated that it would have been physically impossible for Sheila to have reached the trigger to shoot herself with the silencer attached.[79]

Julie Mugford's allegations

Background

A month after the murders Bamber's girlfriend, Julie Mugford, changed her statement, as a result of which Bamber was arrested. He and Mugford had started dating in 1983 when she was a 19-year-old student at Goldsmith's College in London; she was still studying there when the killings occurred. Mugford admitted to a brief background of dishonesty. She had been cautioned in 1985 for using a friend's chequebook to obtain goods worth around £700, after it had been reported stolen; she said she and the friend had repaid the money to the bank. She also acknowledged having helped Bamber in March or April 1985 to steal just under £1,000 from the office of the Osea Road caravan site his family owned; she said he had staged a break-in to make it appear that strangers were responsible. The admission added to the picture of her own and Bamber's lack of credibility.[50]

As part of their submission to the Criminal Cases Review Commission in 2012, Bamber's lawyers found a letter dated 26 September 1985 showing that the assistant director of public prosecutions who prepared the case against Bamber had suggested that Mugford not be prosecuted for the burglary, the cheque fraud, and for a further offence of selling cannabis. She subsequently testified against Bamber during his trial in October 1986. The judge told the jury that they could convict Bamber on Mugford's testimony alone.[81][82]

Statements to police

Mugford was at first supportive of Bamber after the murders; newspaper photographs of the funeral show him weeping and hanging onto her arm. On the day after the killings, she told police that she had received a telephone call from him at about 3:30 am on 7 August, shortly after the murders, during which he sounded worried and said, "There's something wrong at home." She said she had been tired and had not asked what it was.[50]

Her position toward Bamber changed on 3 September 1985, after they rowed about his involvement with another woman. She threw something at him, slapped him, and he twisted her arm up her back. She went to the police four days later and changed her statement.[50] In the second statement she said he had talked disparagingly about his "old" father, his "mad" mother, his sister who he said had nothing to live for, and the twins who he said were disturbed. Bamber denied having said these things and argued that Mugford was motivated by jealousy, but other witnesses offered similar testimony. Mugford's mother said Bamber had told her he hated his adoptive mother, and that he had described her as mad. A friend of Mugford's testified that Bamber had said around February 1985 that his parents kept him short of money, his mother was a religious freak, and "I fucking hate my parents." A farm worker testified that Bamber seemed not to get on with Sheila and had once said: "I'm not going to share my money with my sister."[83]

In discussions Mugford said she had dismissed as fantasies, she alleged that Bamber had said he wanted to sedate his parents and set fire to the farmhouse. He reportedly said Sheila would make a good scapegoat. Mugford alleged he had discussed entering the house through the kitchen window because the catch was broken, and leaving it via a different window that latched when it was shut from the outside.[83]

She said she had spent the weekend before the murders with him in his cottage in Goldhanger, where he had dyed his hair black. She also said that she had seen his mother's bicycle there. This was significant because the prosecution alleged that he had used the bicycle to cycle between his cottage and the farmhouse on the night of the murders. She told police Bamber had telephoned her at 9:50 pm on 6 August to say he had been thinking about the crime all day, was pissed off, and that it was "tonight or never." A few hours later, at 3:00–3:30 am on 7 August, she said he phoned her again to say: "Everything is going well. Something is wrong at the farm. I haven't had any sleep all night ... bye honey and I love you lots." Her flatmates' evidence suggested that call had come through closer to 3 am. He called her later during the morning of 7 August to tell her that Sheila had gone mad, and that a police car was coming to pick her up and bring her to the farmhouse. When she arrived there, she said he had pulled her to one side and said: "I should have been an actor."[83]

Later that evening, on 7 August, she asked Bamber whether he had done it. He said no, but that a friend of his had, whom he named; the man was a plumber the family had used in the past. Bamber allegedly said he had told this friend how he could enter and leave the farmhouse undetected, and that one of his instructions had been for the friend to telephone him from the farm on one of the phones in the house that had a memory redial facility, so that if the police checked it, it would give him an alibi. Everything had gone as planned, he said, except that Nevill had put up a fight, and the friend had become angry and shot him seven times. The friend had allegedly told Sheila to lie down and shoot herself last, Bamber said. The friend then placed the Bible on her chest so she appeared to have killed herself in a religious frenzy. The children were shot in their sleep, he said. Mugford said Bamber claimed to have paid the friend £2,000.[83]

Bamber's arrest

As a result of Mugford's statement Bamber was arrested on 8 September 1985, as was the friend Mugford said he had implicated, although the latter had a solid alibi and was released. Bamber told police Mugford was lying because he had jilted her. He said he loved his parents and sister, and denied that they had kept him short of money; he said the only reason he had broken into the caravan site with Mugford was to prove that security was poor. He said he had occasionally gained entry to the farmhouse through a downstairs windows, and had used a knife to move the catches from the outside. He also said he had seen his parents' wills, and that they had left the estate to be shared between him and Sheila. As for the rifle, he told police the gun was used mostly with the silencer off because it would otherwise not fit in its case.[84]

He was bailed from the police station on 13 September, after which he went on holiday to Saint-Tropez. Before leaving England, he returned to the farmhouse, gaining entry by the downstairs bathroom window. He said he did this because he had left his keys in London and needed some papers from the house for the trip to France; he entered through the window rather than borrow keys from the farm's housekeeper who lived nearby. When he returned to England on 29 September, he was re-arrested and charged with the murders.[84][85]

Trial, October 1986

Bamber was tried in October 1986 before Mr Justice Drake and a jury at Chelmsford Crown Court, during a trial that lasted 19 days. The prosecution was led by Anthony Arlidge QC, and the defence by Geoffrey Rivlin QC, supported by Ed Lawson, QC.[75] The Times wrote that Bamber cut an arrogant figure in the witness box. At one point when prosecutors accused him of lying, he replied: "That is what you have got to establish."[1]

Prosecution case

The prosecution case was that Bamber had been motivated by hatred and greed. They argued that he had left the farm around 10 pm on 6 August 1985, and returned by bicycle in the early hours of the morning, using a route that avoided the main roads. He had entered the house through a downstairs bathroom window, taken the rifle with the silencer attached, and gone upstairs.[86]

He had shot June in her bed, but she had managed to get up and walk a few steps before collapsing and dying. He had shot Nevill in the bedroom too, but Nevill was able to get downstairs where he and Bamber had fought in the kitchen, before Bamber shot him several times in the head. He had shot Sheila in the main bedroom, and had shot the children in their beds, in their own bedroom, as they slept.[86]

They argued that Bamber had then set about arranging the scene to make it appear that Sheila was the killer. He had discovered that she could not have reached the trigger with the silencer attached, so he had removed it and placed it in the cupboard, then placed a Bible next to her body to introduce a religious theme. He had removed the kitchen phone from its hook, left the house via a kitchen window, and banged it from the outside so that the catch dropped back into position. He had then cycled home. Shortly after 3 am, he had telephoned Mugford, then the police at 3:26 am to say he had just received a frantic call from his father. To create a delay before the bodies were discovered, he had not called 999, had driven slowly to the farmhouse, and had told police that his sister was familiar with guns, so that they would be reluctant to enter.[86]

The prosecution argued that Bamber had not received a call from his father, that Nevill was too badly injured after the first shots to have spoken to anyone, that there was no blood on the kitchen phone that had been left dangling, and that Nevill would have called the police before calling Bamber.[87] The prosecution position was that, if the call to Bamber really had been the last thing the father had done before shots were fired, and if he thereafter dropped the receiver, the line to Bamber's home would have remained open for one to two minutes, and Bamber would not have been able to telephone the police immediately to let them know about his father's call, as he said he had.[56] That the line would not have cleared in time for him to call the police is one of several disputed points.[88]

The silencer played a central role. It was deemed to have been on the rifle when it was fired, because of the blood found inside it. The prosecution said the blood had come from Sheila's head, when the silencer was pointed at her. Expert evidence was submitted that, given her injuries after the first shot, Sheila could not have shot herself, placed the silencer in the downstairs cupboard, then run back upstairs to where her body was found. There was also expert testimony that there were no traces of gun oil on her nightdress, despite 25 shots having been fired and the gun having been reloaded at least twice.[87]

Prosecutors argued that, had Sheila killed her family then discovered she could not commit suicide with the silencer fitted, it would have been found next to her; there was no reason for her to have returned it to the gun cupboard. That she had carried out the killings was further discounted because, it was argued, she was mentally well at the time, had no interest in or knowledge of guns, lacked the strength to overcome her father, and there was no evidence on her clothes or body that she had moved around the crime scene or been involved in a struggle.[87]

Defence case

The defence maintained that the witnesses who said Bamber disliked his family were lying or had misinterpreted his words. Mugford had further lied about Bamber's confession, they said, because he had betrayed her, and she wanted to stop him from being with anyone else. No one had seen him cycle to and from the farm. There were no marks on him on the night that suggested he had been in a fight, and no blood-stained clothing of his was recovered. The reason he had not gone to the farm as quickly as he should have when his father telephoned was that he was afraid.[89]

They argued that Sheila was the killer, and that she did know how to handle guns, because she had been raised on a farm and had attended shoots when she was younger. She had a very serious mental illness, had said she felt she was capable of killing her children, and the loaded rifle had been left on the kitchen table by Bamber. There had been a recent family argument about placing the children in foster care.[89]

The defence also argued that people who have carried out so-called "altruistic" killings have been known to engage in ritualistic behaviour before killing themselves, and that Sheila might have placed the silencer in the cupboard, changed her clothes and washed herself, which would explain why there was little lead on her hands, or sugar from the floor on her feet. There was also a possibility that the blood in the silencer was not hers, the defence said, but was a mixture of Nevill's and June's.[89]

Summing up, verdict

The judge said there were three crucial points, in no particular order. Did the jury believe Julie Mugford or Jeremy Bamber? Were they sure that Sheila was not the killer who then committed suicide? He said this question involved another: was the second, fatal, shot fired at Sheila with the silencer on? If yes, she could not have fired it. Finally, did Nevill call Bamber in the middle of the night? If there was no such call, it undermined the entirety of Bamber's story, and the only reason he would have had to invent the phone call was that he was responsible for the murders.[8]

The jury found Bamber guilty on 28 October 1986 by a majority of ten to two; had one more juror supported him, he would not have been convicted. The judge told him he was "evil, almost beyond belief" and sentenced him to five life terms, with a recommendation that he serve at least 25 years.[90]

Appeals

Leave to appeal refused, 1989, 1994

Bamber first sought leave to appeal in November 1986, arguing that the judge had misdirected the jury. The application was heard and refused by a single judge in April 1988. Bamber's lawyer requested a full hearing before three judges, arguing that the trial judge's summing up had been biased against Bamber, that his language had been too forceful, and that he had undermined the defence by advancing his own theory. The lawyer also argued that the defence had not pressed Julie Mugford about her dealings with the media, but should have, because as soon as the trial was over her story began to appear in newspapers. The judges rejected the application in March 1989.[91]

Because the trial judge had criticized the police investigation, Essex Police held an internal inquiry, conducted by Detective Chief Superintendent Dickinson. Bamber alleged this report confirmed that evidence had been withheld by the police, so he made a formal complaint, which was investigated in 1991 by the City of London Police. This process uncovered more documentation, which Bamber used to petition the Home Secretary in September 1993 for a referral back to the Court of Appeal, refused in July 1994.[92]

During this process, the Home Office declined to give Bamber the expert evidence it had obtained, so Bamber applied for judicial review of that decision in November 1994; this resulted in the Home Office handing over its expert evidence. In February 1996 the Essex police destroyed many of the original trial exhibits without informing Bamber or his lawyers. The officer responsible said he had not been aware that the case was on-going.[92]

Court of Appeal, 2002

The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) was established in April 1997 to review allegations of miscarriage of justice, and Bamber's case was passed to them at that time.[93] The CCRC referred the case to the Court of Appeal in March 2001 on the grounds that new DNA testing on the silencer constituted fresh evidence.[94]

The appeal was heard at the Royal Courts of Justice by Lord Justice Kay, Mr Justice Wright, and Mr Justice Henriques from 17 October to 1 November 2002, and the decision published on 12 December. The prosecution was represented by Victor Temple QC, and Bamber by Michael Turner QC.[50] Bamber brought 16 issues to the attention of the court, 14 about failure to disclose evidence or the fabrication of evidence, and two (points 14 and 15) related to the silencer and DNA testing. Point 11 was withdrawn by the defence.[95]

- Hand swabs from Sheila Caffell[96]

- Testing of hand swabs[97]

- Disturbance of crime scene[98]

- Evidence relating to windows[99]

- Timing of phone call to Julie Mugford[100]

- Credibility of Julie Mugford[101]

- Letter from Colin Caffell[102]

- Statement of Colin Caffell[103]

- Photograph showing the words "I hate this place"[53]

- Bible[104]

- Proposed purchase by Bamber of a Porsche[105]

- Telephone in the kitchen[106]

- Scars on Bamber's hands[107]

- Blood in the silencer[108]

- DNA evidence[109]

- Police misconduct[110]

Although most of the issues were reviewed by the court, the reason for the referral was point 15, the discovery of DNA on the silencer, the result of a test not available in 1986. The silencer evidence during the original trial came from a Mr. Hayward of the Forensic Science Laboratory. He had found human blood inside the silencer, and had stated that its blood group was consistent with it having come from Sheila. He said there was a remote possibility that it was a mixture of blood from Nevill and June.[108]

Mark Webster, an expert instructed by Bamber's defence team, argued that Hayward's tests had been inadequate, and that there was a real possibility, not a remote one, that the blood had come from Nevill and June. This was a critical point, because the prosecution case rested on the silencer having been on the gun when Sheila was shot, something she could not have done herself because of the length of her arms. If she was shot with the silencer on the gun, it meant that someone else had shot her. If her blood was inside the silencer it supported the prosecution's position, but if the blood belonged to someone else, that part of the prosecution case collapsed.[108]

The defence argued that new tests comparing DNA in the silencer to a sample from Sheila's biological mother suggested that the "major component" of the DNA in the silencer had not come from Sheila.[111] A DNA sample from June's sister suggested that the major component had come from June, they argued.[109]

The court concluded that June's DNA was in the silencer, that Sheila's DNA may have been in the silencer, and that there was evidence of DNA from at least one male. The judges' conclusion was that the results were complex, incomplete, and also meaningless because they did not establish how June's DNA came to be in the silencer years after the trial, did not establish that Sheila's was not in it, and did not lead to a conclusion that Bamber's conviction was unsafe.[109] In a 522-point judgment dismissing the appeal, the judges said that there was no conduct on the part of the police or prosecution that would have adversely affected the jury's verdict, and that the more they examined the details of the case, the more they thought the jury had been right.[112]

Against whole-life tariff

The trial judge recommended a minimum term of 25 years, but in December 1994 Home Secretary Michael Howard ruled that Bamber should remain in prison for the rest of his life. In May 2008 Bamber lost a High Court appeal against the whole-life tariff before Mr. Justice Tugendhat.[113][114] This was upheld by the Appeal Court in May 2009.[115]

Bamber and three other British whole-life prisoners appealed to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France, but the appeal was rejected in January 2012.[116] Bamber and two prisoners, Douglas Vinter and Peter Moore, appealed that decision too, and in July 2013 the European Court's Grand Chamber ruled that keeping the prisoners in jail with no prospect of release or review may not be compatible with Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment.[117][118]

Criminal Cases Review Commission

Campaign

A campaign gathered pace over the years to secure Bamber's release, and from March 2001 several websites were set up to discuss the evidence.[119] Bamber used one of them in 2002 to offer a £1m reward for evidence that would overturn his conviction.[120]

His case was taken up by MPs George Galloway and Andrew Hunter, and journalist Bob Woffinden. Woffinden argued between 2007 and 2011 that Sheila had shot her family, then watched as police gathered outside the house before shooting herself. He changed his mind in 2011 and stated that he believed Bamber was guilty.[121]

In 2004 Bamber launched a fresh attempt to obtain another appeal, with a defence team that included Giovanni di Stefano.[122][123] (In March 2013 di Stefano was sentenced in the UK to 14 years in prison for having fraudulently presented himself as a lawyer.)[124] Di Stefano applied unsuccessfully in March 2004 to have the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) refer the case back to the Court of Appeal.[125][126][127] The defence team made a fresh submission in January 2009.[128]

Defence arguments

Crime scene

The defence argues that the first officers to enter the farmhouse inadvertently disturbed the crime scene, then reconstructed it. Crime-scene photographs not made available to the original defence show Sheila's right arm and hand in slightly different positions in relation to the gun, which is lying across her body. The gun itself also appears to have moved. Former Lancashire Detective Chief Superintendent Mick Gradwell, shown the photographs by the Guardian and Observer, said in January 2011: "The evidence shows, or portrays, Essex police having damaged the scene, and then having staged it again to make it look like it was originally. And if that has happened, and that hasn't been disclosed, that is really, really serious."[129][130]

Sheila's body, time of death

The defence disputes the location of Sheila's body. The police said they found her upstairs with her mother, but PC Collins reported seeing through a window what he thought was the body of a woman near the kitchen door.[131] Later police reports said that only Nevill had been found in the kitchen.[132] A retired police officer who worked on the case said in 2011 that the first police logs were simply mistaken in reporting that a woman's body had been found downstairs.[133] Bamber's lawyers argue that images of Sheila taken by a police photographer at around 9 am on 7 August 1985 show her blood was still wet, and that, had she been killed before 3:30 am as the prosecution said, it would have congealed by 9 am.[134]

Scratch marks on mantelpiece

The defence commissioned a report from Peter Sutherst, a British forensic photographic expert, who was asked in 2008 to examine negatives of the kitchen taken on the day of the murders and later. In his report, dated 17 January 2010, Sutherst argued that scratch marks in paintwork on the kitchen mantelpiece had been created after the crime-scene photographs had been taken. The prosecution alleged that the marks had been made during the struggle in the kitchen between Bamber and his father, as the silencer, attached to the rifle, had scratched against the mantelpiece. The prosecution said that paint chips identical to the paint on the mantelpiece were found on or inside the silencer.[122]

Sutherst said the scratch marks appeared in photographs taken on 10 September 1985, 34 days after the murders, but were not visible in the original crime-scene photographs. He also said he had failed to find in the photographs any chipped paint on the carpet below the mantelpiece, where it might have been expected to fall had the mantelpiece been scratched during a struggle.[122] He was asked by the CCRC to examine a red spot on the carpet visible in photographs underneath the scratches on the mantelpiece. He said the red spot matched a piece of nail varnish missing from one of Sheila's toes.[135] He concluded that the scratch marks on the mantel had been created after the day of the murders.[122]

Police telephone, radio logs

Police telephone logs had been entered as evidence during the trial, but had not been noticed by Bamber's lawyers. Bamber's new defence team said the logs showed that someone calling himself Mr. Bamber had telephoned police on the night of the attack to say his daughter had "gone berserk" with one of his guns.[57] Stan Jones, a former detective sergeant who worked on the case, told the Essex Chronicle in 2010: "The only person who telephoned the police was Jeremy Bamber. There is no way his father phoned. To suggest it is farcical."[133] A separate log of a police radio message shows there was an attempt to speak to someone inside the farmhouse that night, as police waited outside to enter, but there was no response. Police say the officers had simply made a mistake.[136]

Silencer

Gun experts commissioned by the defence argued that the injuries were consistent with the silencer not having been used, and that its absence would explain burn marks on Nevill's body. That the gun had a silencer on it during the murders was central to the prosecution's case. The experts involved in compiling the report were David Fowler, chief medical examiner for the state of Maryland in the United States; Ljubisa Dragovic, chief medical examiner of Oakland county in Michigan; Marcella Fierro, former chief medical examiner for the state of Virginia; Daniel Caruso, chief of burn services at the Arizona Burn Center; and Dr. John Manlove, a British forensic scientist.[137][138]

Letter regarding Mugford

Bamber's lawyers told the press in March 2012 that they had found a letter, dated 26 September 1985, from John Walker, assistant director of public prosecutions, to the Chief Constable of Essex Police, discussing the prosecution of Bamber. Walker had written that he was suggesting, "with considerable hestitation," that Mugford be told she would not be prosecuted for drugs offences, burglary and cheque fraud, offences she had confessed to during her police interviews regarding Bamber. Bamber's lawyers said this raised the possibility that she had been persuaded to testify in the hope that charges would not be pursued. According to the Guardian, the trial judge told the jury that they could convict Bamber based on Mugford's testimony alone.[81]

CCRC response, 2012

The CCRC provisionally rejected Bamber's 2009 submission in February 2011 in an 89-page document. It invited his lawyers to respond within three months, extended the deadline to allow them to study all 406 crime-scene photographs,[128] and in September 2011 granted them an indefinite period in which to pursue an additional line of inquiry.[139][140] The CCRC finally rejected the application in April 2012 in a 109-page report, which said the submission had not identified any new evidence or legal argument that would raise the real possibility of the Court of Appeal overturning the conviction.[5] The High Court turned down Bamber's application for a judicial review of that decision in November 2012.[141] As of May 2013, according to his website, Bamber's defence team was preparing a fresh submission.[142]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e "Murder most foul, but did he do it?", The Times, editorial, 18 March 2001.

- ^ Bamber, R v [2002] EWCA Crim 2912 (12 December 2002), 1. Text.

- ^ Peter Hutchison, "Jeremy Bamber: a profile", The Daily Telegraph, 11 February 2011.

- ^ David James Smith, "And by dawn they were all dead", The Sunday Times Magazine, 11 July 2010, 18–22 (archived); for extended family, 19–20.

- ^ a b Eric Allison, "Jeremy Bamber murder appeal bid thrown out", The Guardian, 26 April 2012.

- ^ Eric Allison and Mark Townsend, "Gun experts raise doubts over Jeremy Bamber murder verdict", The Observer, 4 February 2012.

- ^ Eric Allison, et al., "Jeremy Bamber: Will new evidence bring historic third appeal?", Guardian Films, 30 January 2011, from 08:00 mins.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 153.

- ^ For dates of birth, Colin Caffell, In Search of the Rainbow's End, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 1994, 15.

- ^ For other biographical details, Claire Powell, Murder at White House Farm, London: Headline Book Publishing, 1994, 18, 21–22, 25.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 12, 151.v(c).

- ^ Powell 1994, 34, 52–53; for the psychiatrist, 228–232; for Sheila's relationship with June, 230.

- ^ For the praying, Smith 2010, 18–19.

- ^ Roger Wilkes, Blood Relations: Jeremy Bamber and the White House Farm Murders, London: Robinson Publishing, 1994, 35.

- ^ Carol Ann Lee, The Murders at White House Farm, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 2015, 21.

- ^ Powell 1994, 21–22, 29, 32; Caffell 1994, 128, 131.

- ^ Caffell 1994, 136–137; Powell 1994, 229.

- ^ Powell 1994, 36–37; Caffell 1994, 139–141.

- ^ Powell 1994, 42–45, 50; [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 16–17. Text.

- ^ Powell 1994, 59–65.

- ^ Lee 2015, 111; Powell 1994, 74–79.

- ^ Powell 1994, 80.

- ^ Powell 1994, 51–52.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 373. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 84. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 85. Text.

- ^ a b Powell 1994, 81–82.

- ^ Powell 1994, 230; [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 85. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 86–87. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 371–372. Text; Eric Allison, Simon Hattenstone, "Is Jeremy Bamber innocent?", The Guardian, 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 370. Text.

- ^ Powell 1994, 231; [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 88–89. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 83. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 82. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 30, 143. Text.

- ^ Powell 1994, 174.

- ^ Lee 2015, 25; Powell 1994, 265.

- ^ Powell 1994, 40.

- ^ Powell 1994, 47–48.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 18. Text.

- ^ Lee 2015, 79.

- ^ Eric Allison and Mark Townsend, "The new evidence Jeremy Bamber says could end his 26 years in prison", The Observer, 30 January 2011.

- ^ a b Eric Allison and Simon Hattenstone, "Is Jeremy Bamber innocent?", The Guardian, 10 February 2011.

- ^ For psychopath, "Ofcom rejects convicted killer Jeremy Bamber's complaint", BBC News, 26 September 2011; for an interview with a cousin, Interview with David Boutflour, BBC News, 9 July 2013.

- ^ Dominic Kennedy, "Jeremy Bamber’s father ‘foresaw’ family slaughter at farm", The Times, 8 November 2013.

- ^ George Galloway, "Lie Detectors: Jeremy Bamber", House of Commons, 15 May 2007.

- ^ a b Smith (Sunday Times) 2010, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Matthew Moore, "Jeremy Bamber claims he was framed for murder by cousins", The Daily Telegraph, 12 July 2010.

- ^ "Killer's family cash claim fails", BBC News, 6 October 2004.

- ^ a b c d e [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 12. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 21, 30. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 22. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 392–404. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 373–377. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 23. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 22. Text.

- ^ a b c d e f Nick Collins, "Jeremy Bamber murders: new evidence could clear killer", The Daily Telegraph, 5 August 2010; Second police log (webcite).

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 24–27. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 29, 134. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 141. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 8. Text.

- ^ Lee 2015, 163.

- ^ Lee 2015, 168.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 29. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 30. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 39. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 58–65. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 236, 239. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 33. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 41–42. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 43. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 36, 44. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 45–53. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 52. Text.

- ^ a b c d David Connett, "Past crimes: The Bamber files", The Independent, 8 August 2010.

- ^ Bamber, R v [2009] EWCA Crim 962 (14 May 2009), 11. Text.

- ^ Powell 1994, 91.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 72. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 73–80. Text.

- ^ Smith (Sunday Times) 2010, 20.

- ^ a b Eric Allison, "Jeremy Bamber in new challenge to conviction for murdering family", The Guardian, 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Jeremy Bamber: prosecutor's correspondence with police—full documents", The Guardian, 29 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 94–120. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 127–136. Text.

- ^ "Bamber killings: son remanded", The Glasgow Herald, 1 October 1985.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 145–150. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 151. Text.

- ^ Andrew Green, "Mystery of the White House Farm: will we ever know the truth?", Innocent, undated (webcite).

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 152. Text.

- ^ Ian Burrell, "Jeremy Bamber has served 15 years for the murder of his family. But was he guilty?" The Independent, 13 March 2001.

- ^ Powell 1994, 276, 283–285; [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 155–158. Text.

- ^ a b [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 159ff. Text.

- ^ "Commission refers conviction of Jeremy Bamber to Court of Appeal", Criminal Cases Review Commission, 12 March 2001.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 166ff. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 169–174. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 175–213. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 214–232. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 233–260. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 261–288. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 289–330. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 331–366. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 367–377. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 378–391. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 405–427. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 428. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 429–443. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 444–451. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 452–475. Text.

- ^ a b c [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 476–508. Text.

- ^ [2002] EWCA Crim 2912, 509–511. Text.

- ^ Peter Foster, Thomas Penny, "Appeal Court reviews Bamber 'massacre'", The Daily Telegraph, 12 March 2001.

- ^ Sarah Hall, "Bamber loses appeal over murder convictions", The Guardian, 13 December 2002.

- ^ "R v Jeremy Neville Bamber" [2008] EWHC 862 (Queens Bench), Case No. 2005/52/MTR, before Mr Justice Tugendhat, 16 May 2008.

- ^ "Killer's life term is 'justified'", BBC News, 14 May 2009.

- ^ [2009] EWCA Crim 962, 4. Text.

- ^ "Murderers lose appeal against whole life tariffs", BBC News, 17 January 2012.

- ^ Owen Bowcott, Eric Allison, "Whole-life jail terms without review breach human rights - European court", The Guardian, 9 July 2013.

- ^ Owen Bowcott, "Murderers may face 100 years in jail under plans backed by David Cameron", The Guardian, 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Murderer's website sparks anger", Birmingham Evening Mail, 5 March 2001.

- ^ "Killer Bamber offers £1m reward", BBC News, 22 December 2002.

- ^ Leo McKinstry, "Lack of appeal", The Spectator, 7 April 2012; Lee 2015, 399.

- ^ a b c d Mark Townsend, Eric Allison, "Jeremy Bamber did not murder his family, insists court expert", The Observer, 21 February 2010.

- ^ Mark Townsend, Eric Allison, Shehani Fernando, Maggie Kane, "Jeremy Bamber conviction challenged by new photographic evidence", The Observer, 21 February 2010.

- ^ "Bogus Italian lawyer Giovanni di Stefano found guilty", BBC News, 27 March 2013.

- ^ "Bamber in new bid to clear name", BBC News, 2 August 2005.

- ^ Andrew Hunter, "Jeremy Bamber", House of Commons, 9 February 2005.

- ^ "MP 'would offer bail' for killer", BBC News, 8 December 2004.

- ^ a b Eric Allison, Peter Walker, "Jeremy Bamber loses attempt to appeal", The Guardian, 11 February 2011.

"Jeremy Bamber's lawyers given more time to prepare case", BBC News, 19 July 2011.

- ^ Eric Allison, et al., "Jeremy Bamber: Will new evidence bring historic third appeal?", Guardian Films, 30 January 2011, from 06:36 mins for the detective's name; from 08:00 mins for the quote.

- ^ Mick Gradwell, "Which adopted child shot farmhouse family?", Lancashire Evening Post, 10 February 2011.

- ^ Essex police log, jeremybamber.com.

- ^ "R v Jeremy Bamber" [2002], EWCA, Crim 2912, paras 33, 35, 36.

- ^ a b "Maldon: Detective rejects new evidence Bambi went 'berserk' as farcical", Essex Chronicle, 12 August 2010.

- ^ "Request for pardon from Secretary of State", Studio Legale Internazionale, 3 August 2005, 2 (webcite).

- ^ Eric Allison, Mark Townsend, "The new evidence Jeremy Bamber says could end his 26 years in prison", The Observer, 30 January 2011.

- ^ Scott Lomax, Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?, Stroud: The History Press, 2008, image 8, between 128 and 129.

- ^ Eric Allison and Mark Townsend, "Gun experts raise doubts over Jeremy Bamber murder verdict", The Observer, 4 February 2012.

- ^ For burn marks, "R v Jeremy Bamber", 12 December 2002, para 42.

- ^ "Jeremy Bamber's lawyers get further time to prepare", BBC News, 2 September 2011.

- ^ Eric Allison, Mark Townsend, "Gun experts raise doubts over Jeremy Bamber murder verdict", The Observer, 4 February 2012.

- ^ "Jeremy Bamber's latest action against conviction fails", BBC News, 29 November 2012.

- ^ "CCRC Applications", jeremy-bamber.co.uk, 22 May 2013; Dominic Kennedy, "Bamber challenges murder conviction over gun evidence", The Times, 2 December 2013.

Bibliography

- News reports are cited above only.

Hearings

- Bamber, R v [2002] EWCA Crim 2912 (12 December 2002). Text.

- Bamber, R v [2009] EWCA Crim 962 (14 May 2009). Text.

Books

- Lee, Carol Ann. The Murders at White House Farm, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 2015.

- Powell, Claire. Murder at White House Farm, London: Headline Book Publishing, 1994.

- Scott Lomax, Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?, Stroud: The History Press, 2008.

- Wilkes, Roger. Blood Relations: Jeremy Bamber and the White House Farm Murders, London: Robinson Publishing, 1994.

Further reading

Television

- Bambers' funeral service, Anglia Television, August 1985, from 00:01:31.

- Real Crimes: Jeremy Bamber, Anglia Television. 2003.

- The White House Farm Murders, Yorkshire Television. 1993.

Books/articles

- Appleyard, Nick. "Tonight's the Night," Life Means Life, London: John Blake Publishing Ltd, 2009.

- D'Cruze, Shani; Walklate, Sandra L.; Pegg, Samantha. "The White House Farm murders," Murder: Social and Historical Approaches to Understanding Murder and Murderers, Uffculme: Willan, 2006.

- Howard, Amanda. "Jeremy Bamber," A Killer in the Family, London: New Holland Publishers, 2013.

- Leyton, Elliott. Sole Survivor: Children Who Murder Their Families, London: John Blake Publishing Ltd, 2009.