William James Hinchey

William James Hinchey (December 5, 1829 – September 9, 1893) was an Irish-American painter, Civil War correspondent, and diarist. His work serves as a visual record of the Santa Fe Trail, the Civil War, and life in 19th century Missouri. Additionally, his journals and business records provide insight into life as a working artist on the American Frontier. While primarily a portraitist, his most famous painting today is the Dedication of Eads Bridge.

Early life

[edit]William James Hinchey was born December 5, 1829, in Dublin, Ireland to Paul Chilrose Hinchey and his wife, Mary Ann Doyle Hinchey. Paul was a devout Protestant and son of a minister and Mary was a devout Catholic, which resulted in all eight of their children being double-baptized into both churches and Mary secretly taking the children to hear Catholic mass.[1]

A slight child, the Hinchey family physician recommended William take daily walks for exercise. Hinchey was encouraged by his family to draw and sketch, and he carried pencils and a sketchbook along with him on his walks. Hinchey's penchant for long walks and frequent sketching continued throughout his life; his son noted Hinchey kept up this habit until his death. Hinchey's parents further encouraged his artistic development by paying for painting and drawing lessons.[2]

Hinchey began selling pencil portraits at the age of twelve. Hinchey recollects in an 1850 diary entry that at twelve he was already determined to be a professional portrait painter. By the time he was 16, Hinchey had progressed to portraits in oil and pastels. Hinchey reported he was paid well enough for his commissions to pay half of the tuition of Trinity College.[3]

Hinchey went on to attend Oxford. During his time in Oxford he began to advocate for Irish Home Rule, participating in street protests and associating with a group of students that was responsible for minor mischief, such as breaking windows in government buildings. English authorities began to pay more serious attention when the group began organizing on behalf of Irish tenant farmers for land reform in the areas outside of Dublin. Fortunately for Hinchey his father, who worked as a government building inspector in Dublin, was tipped off that William was about to be arrested for conspiring against the crown. Hinchey quickly relocated to Paris.[1]

While Hinchey never returned permanently to Ireland, his dedication to an independent Ireland never flagged – along with naming one of his sons for Robert Emmett, Commander of the Irish Rebellion of 1803, his last words were his wish to see Ireland freed from British rule.[1] Despite his experience at Oxford and subsequent self-imposed exile, for the remainder of this life Hinchey continued to advocate for other progressive social and governmental reform.[citation needed]

Exile in France

[edit]Facing self-imposed exile from Ireland, Hinchey settled in Paris where he continued to study art. In need of funds to support himself, during this period he continued to work as a painter and gilder. By 1854, with the assistance of Dr. Mile, the head of the Irish College in Paris, Hinchey had established a network for commissions for portraits, sales of old master copies, and religious art.[2]

While at the Louvre painting, Hinchey was approached by Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy. Lamy was the first bishop for the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, whose bishopric covered the New Mexico Territory, including today's New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of Nevada and Colorado. Lamy been made aware of Hinchey through a mutual friend and was on the hunt for an artist to travel back to Santa Fe with his party to help revive the Spanish missions.

At the Louvre, Lamy offered Hinchey a papal contract for what amounted to the position of artist-in-residence for the Archdiocese of Santa Fe. In exchange for an all-expenses-paid (except clothing) round-trip to Santa Fe plus a salary, Hinchey would be responsible for painting religious works, repairing existing paintings, and restoring and creating frescos.[3][1] The decision to accept was not hard for Hinchey. Enamored by America's progressive democracy compared to the monarchies he saw around him in Europe, Hinchey recorded in his diary:

I had read much and dreamed of the glory of free America, and had felt a great gratitude to the United States as the hospitable refuge of those who fled there from the greedy grasp of Europe's monsters and mighty ones. Enterprising exiles from every country had gone there, to the land where there was to be seen the native red men, these unsubduable sons of liberty. Where also were to be seen the great grizzly bear and the giant bison and beyond, the Mexican descendants of Montezuma. Twas not hard to pursuade me into leaving for a year my position in Paris, to indulge in such an excursion. The contrast between the Pinnacle of Art and Refinement [Paris] and the wild untamed savagery of the western wilds so far from daunting me, became the very charm of the enterprise that appealed to me. Liberal terms being offered me, I agreed to go, despite the discussions and protestations of my friends..

— W.J. Hinchey, June 2nd 1854[2]

Hinchey planned to return to Paris after the contract was over.[1] To prepare for the trip, Hinchey returned to London from Paris, then to Ireland for a visit with his family, then back to France where he met Bishop Lamy's party. Together, they took a boat from Le Havre for New York City. After a two-week sea crossing the party took a train to Cincinnati, then to Louisville, where they took a boat to St. Louis where they switched boats for Independence, Missouri to start the Santa Fe Trail by wagon to Santa Fe.[citation needed]

Santa Fe & The Santa Fe Trail

[edit]Hinchey's diaries and sketchbooks created on his trips to and from Santa Fe on the Santa Fe Trail resulted in the creation of an important written and visual record of trail life.[3] Hinchey's trips took 47 and 39 days. While no major disasters befell Hinchey on either trip, his diary records snowstorms, windstorms, rainstorms, sentry duty for raiding parties, and prairie fires alongside the day-to-day work of a wagon train collecting firewood or buffalo chips, hunting, and caring for stock. In what reads today as almost a parody of life on a frontier trail, Hinchey records the status of the Bishop's party at Westport on Friday the 22nd of September 1854, after only 12 days of camping waiting to start the trail:

Today, poor John, one of our Irishmen, was thrown off his horse (the young white one) and hurt…George, the hunter, had colic; Monsieur Abbe Vaur’s hands were blistered; Padre Ortiz was sick generally; and there was the man [Monsieur Eguillion] who had shot himself [in the hand the day before]. Also Monsieur Abbe Pollet. I don’t know what was ailing him. Monsieur Pere Avel was horse sore.

— W.J. Hinchey, September 22nd 1854[4]

Hinchey's time working for Bishop Lamy in Santa Fe would be short. He arrived in Santa Fe November 19, 1854 and had decided to leave by January 20, 1855, eventually leaving on February 29, 1855, well short of the year stipulated in his papal contract. While Hinchey disliked Santa Fe, more broadly life on the American frontier had failed to live up to the egalitarian and democratic idyll he envisioned. Hinchey's diary records his frustration with economic injustices like locals selling or pawning their possessions for food and other basic necessities and takes scathing aim at shop owners benefitting off of the impoverished.[2] After witnessing an assault on a local man in the town plaza, Hinchey wrote a letter to the editor of the Santa Fe Star Gazette, published on February 24, 1855, calling out the hypocrisy of Americans for throwing off one oppressor (Britain) while trying to become the oppressor of another:

In the name of justice and humanity, Mr. Editor, what are supposed to be the rights of the natives in this unfortunate territory, at the hands of the United States citizens resident here? Are they to be treated as brutes, unworthy the least consideration; and unpossessed of the slightest attribute for good; or despised and trampled on by their conquerors as beings unworthy even the exercise of toleration, on the part of a people boasting & the citizenship of the freest country in 'the world." Might not these persons who talk so much of that liberty which they seem so well to appreciate, be expected to exercise sympathy for those less fortunate individuals, who though living under the "glorious constitution' are not yet fully cognizant of all the advantages to be derived from the glorious State of things, consequent on such a constitution. Might they not remember, that their own country — now so preeminently free, was once governed by a distant power which ruled It from afar — which formed its then existing constitution and dictated its laws which, believing itself master, tried to oppress it, its own offspring; kindred in blood, in language and religion yet, that out of such wrongs, arose the rights, the glory and the brilliancy which now America enjoys, and which shining afar o'er every sea gladden the heart, illume the features, and enliven the hopes and aspiration of every lover of liberty?

— W.J. Hinchey, February 24th 1855[5]

Nor does Hinchey's diary spare his Catholic coworkers in Santa Fe scorn when they failed to live up to his standards. The day after arriving in Santa Fe, one of the clergy traveling in the Bishop's party died. Hinchey's diary for Sunday November 19, 1854, records his incredulity:

This morning when people got up they found the little Abbie Vaur dead. Dead without the Sacraments! In a Bishops House!! A month sick and snoring priests about him when he breathed his last !!! So much for the preaching and practicing of those fine ecclesiastical gentlemen.

— W.J. Hinchey, November 19th 1854[4]

Life in Missouri

[edit]After leaving Santa Fe, Hinchey wasted no time settling into Independence, Missouri. Within days of arriving, he was advertising himself in the paper as a portrait painter, although his diary records that he also took other work painting signs and banners.[1] Hinchey filled his life in Independence with many mid-nineteenth century American staples: lyceum lectures, debates, and attending Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, Catholic, and Mormon religious revivals. Hinchey abruptly left Independence on May 30, 1856 – one day after finding out a woman he was courting was engaged to another man.[1]

In August 1856 Hinchey was living in St. Louis at the Planter's Hotel, where he met Reverend Jerome Berryman who asked him to teach art and French at his newly established Acadia Valley Seminary, located in the Arcadia Valley of Missouri. William agreed to a one-year contract.[1] While teaching, he met and married one of his students, Lucinda Jane Holloman on August 8, 1857. Lucinda's family was well-established and prominent in Missouri: her father was a state representative and later a judge. The couple initially settled in Alton, Illinois, with Hinchey travelling to his St. Louis studio several times a week before they settled in St. Louis.[4] The couple had six children between 1859 and 1875 — five sons and, finally, one daughter.

By the 1880s, Hinchey was prosperous enough to build a large, Eastlake-style house with a wraparound porch in De Soto, Missouri. The family took portraits on the front steps and played croquet and tennis on the lawn.[5]

Civil War and Work as a War Correspondent

[edit]

During the Civil War, Hinchey continued to work as a portraitist as well as taking on work as a war correspondent for Harper's Weekly, New York Illustrated, and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.[3] As an Irish citizen, in 1861 Hinchey secured letters of passage from the Union Army that permitted him to move about Eastern Missouri, sketching and recording what he saw.[1] Hinchey's work was then engraved and published. While Hinchey's diaries note that he was generally well treated, he was captured at least twice and almost shot as a spy on one occasion due to his detailed notes and sketches of battles, troop numbers, and encampments.[6] During this period in Missouri, Hinchey recorded the Battle of Pilot Knob, the Battle of Fredricktown, and the Battle of Cape Girardeau.[1]

Hinchey continued to work as a portraitist, focusing his efforts on the new market of officers and enlisted men. At first, Hinchey planned to sell portraits in oil on paper at low cost to recently enlisted soldiers, but by January 1862 Hinchey was complaining that many soldiers were running out of money.[1] In May 1862, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to see if the demand for war portraits was greater in the capital. To avoid travel in the border states, Hinchey routed through St. Louis, Chicago, Ft. Wayne, Pittsburgh, and Harrisburg. Hinchey remained in the capital for three months until early August. During this time, Hinchey had a studio in a room inside the Capitol Building across from the Senate Chambers.[3]

Death

[edit]On September 7, 1893, Hinchey was riding the streetcar at Broadway and Poplar streets in downtown St. Louis when he attempted to exit the car and was sucked under, severely fracturing both legs requiring double amputation. Hinchey died in City Hospital two days after surgery, likely from blood poisoning. He was buried in De Soto City Cemetery.

In reporting on Hinchey's accident and later on his death, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat summed up Hinchey as "...an honorable and high-minded gentleman, liberal, large-hearted and true, and has many friends here who will hear of his misfortune with great sorrow; we sincerely hope that he may survive this accident."[7]

Working Practice as an Artist

[edit]

Hinchey operated in a commercial reality – he was not independently wealthy and needed to sell to survive.[3] By the time he arrived in St. Louis, Hinchey had already spent a decade successfully selling work. By the late 1850s, Manuel Joachim de Franca and George Caleb Bingham were already established and successful painters in St. Louis, with de Franca the city's leading portraitist for the upper classes. However, Hinchey's arrival did not start a rivalry as St. Louis was large and prosperous enough to support several working artists and Hinchey courted a less affluent market segment than either of these established painters.[3] Instead, Hinchey's connections to St. Louis’ artistic community and his relationship with de Franca likely helped him secure commissions. Within a few days of arriving in St. Louis in June 1856, de Franca commissioned Hinchey to make a portrait of a young boy. When de Franca approved he commissioned another, this time having Hinchey work from a daguerreotype.[3] When de Franca died in 1865, Hinchey was already a well-established option for the city's merchant middle class.

Photography played an important role in Hinchey's portrait practice, and he often worked from photos.[3] Photographs cut down the time needed for sittings, meaning that the subject could be at work while Hinchey produced portraits in his studio, broadening his appeal to more middle-class customers. The day after arriving in St. Louis, Hinchey's diary records a trip to the Fitzgibbon Gallery, a photography studio.[3] Hinchey used photographs in conjunction with sketches and sittings, and also offered portraits exclusively from photographs.

A surviving price list for Hinchey's studio from the Civil War period lists many options for portraits at various price points providing options for a wide array of potential customers depending on size, materials, and other options such as the inclusion of hands.[8] Hinchey's diaries record he could produce a simpler cabinet size (17x14 inches) portrait in 2–3 days.[3] This would have cost $50-$75 at the time when the average daily wage for a carpenter in Missouri was about $2, a hotel stay ranged from $1-$2 per day, and a six-room house in St. Louis could be rented out for $25 a month.[9][10]

Hinchey also painted and recorded the landscapes and world around him, accepting commissions for landscapes and recording important events. He also continued to work as a correspondent for illustrated newspapers until his death, adding another revenue stream and providing a market for engravings of civic events. Ironically for someone who had expressed his wish since the age of twelve to become a portrait painter, his painting of the Dedication of Eads Bridge on July 4, 1874, today at the St. Louis Art Museum, went on to become his most famous and widely exhibited work,[3] even traveling to Washington D.C. for an exhibition during the nation's bicentennial celebrations.

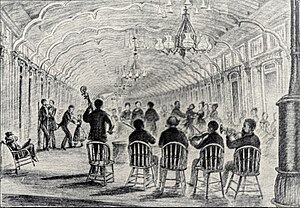

Although not intended as finished works, Hinchey's sketches and diary drawing have also been exhibited for both their artistic and historic merit.[11] Comparison of Hinchey's drawing of the interior of the steamboat Richmond with rare early photographs highlight the detail and accuracy of Hinchey's eye and underscore their importance as visual records for this period in history.

Diaries

[edit]Hinchey met Sir Issac Pitman, the developer of the Pitman shorthand system, in 1850 while attending Oxford University. Hinchey learned the Pitman system from Pitman and for the next 14 years kept a diary in Pitman shorthand.[3] In total, 17 diaries and 10 contemporaneous sketchbooks are known to exist. Hinchey's diaries were largely translated out of shorthand by his son, Steven, in the 1950s. Manuscript copies of the Steven Hinchey translation are held by the State Historical Society of Missouri and the St. Louis Art Museum.

One missing diary covering part of Hinchey's Santa Fe Trail journey was rediscovered by Anna Belle Cartwright in the 1990s and translated by four Independence, Missouri women.[4]

Another diary covering a portion of the Santa Fe Trail trip for three weeks from the Missouri Border to the Cimarron River remains lost. In a surviving diary, on December 20, 1854, Hinchey records his annoyance at losing one of his diaries and records his offer of a reward of $5 (a considerable sum for the time and place) for its return, suggesting that the missing diary may have been misplaced by Hinchey himself in 1854.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Morgan, Jack (February–March 2018). "An Irish Artist's American Odyssey". Irish America. New York, New York: Niall O'Dowd. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Cartwright, Anna Belle (May 1996). "William James Hinchey: An Irish Artist on the Santa Fe Trail, Part 1". Santa Fe Trail Association: Wagon Tracks. 10 (3). Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Springer, Lynn (1974). The Rediscovered Work of William J. Hinchey. St. Louis: The St. Louis Art Museum. LCCN 74014581.

- ^ a b c d Cartwright, Anna Belle (August 1996). "William James Hinchey: An Irish Artist on the Santa Fe Trail, Part 2". Santa Fe Trail Association: Wagon Tracks. 10 (4). Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Cartwright, Anna Belle (November 1996). "William James Hinchey: An Irish Artist on the Santa Fe Trail, Part 3". Santa Fe Trail Association: Wagon Tracks. 11 (1). Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Hinchey, William James; Holloman, John; Holloman, Elizabeth (1998). The W.J. Hinchey Diaries : Portrait of a Community During the Civil War. Iron County Missouri. OCLC 1144683640.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "W.J. Hinchey Obituary". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. St. Louis, Mo. September 9, 1983.

- ^ Springer, Lynn (1974). "Figure 78: List of Prices, ca. 1860-1870". The Rediscovered Work of William J. Hinchey. St. Louis: The St. Louis Art Museum. LCCN 74014581.

- ^ Edmunds, James M. (1866). Statistics of the United States, (including mortality, property, &c.,) in 1860: comp. from the original returns and being the final exhibit of the eighth census, under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior. Govt. Print. Off. p. 512. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Prices and Wages by Decade: 1860-1869". University of Missouri. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Scenes From the Road to Santa Fe: Sketches by William J. Hinchey. Independence, Missouri: National Frontier Trails Center. 1996.