X-bar theory

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

X-bar theory is a theory of syntactic category formation. It embodies two independent claims: one, that phrases may contain intermediate constituents projected from a head X; and two, that this system of projected constituency may be common to more than one category (e.g., N, V, A, P, etc.).

The letter X is used to signify an arbitrary lexical category (part of speech); when analyzing a specific utterance, specific categories are assigned. Thus, the X may become an N for noun, a V for verb, an A for adjective, or a P for preposition.

The term X-bar is derived from the notation representing this structure. Certain structures are represented by X (an X with a bar over it). Because this may be difficult to typeset, this is often written as X′, using the prime symbol or with superscript numerals as exponents, e.g., X1. In English, however, this is still read as "X bar". The notation XP stands for X Phrase, and is at the equivalent level of X-bar-bar (X with a double overbar), written X″ or X2, usually read aloud as X double bar.

X-bar theory was first proposed by Noam Chomsky (1970),[1] building on Zellig Harris's 1951 (ch. 6) approach to categories,[2] and further developed by Ray Jackendoff (1977).[3] X-bar theory was incorporated into both transformational and nontransformational theories of syntax, including GB, GPSG, LFG, and HPSG. Recent work in the Minimalist Program has largely abandoned X-bar schemata in favor of Bare Phrase Structure approaches.

Core concepts

There are three "syntax assembly" rules which form the basis of X-bar theory. These rules can be expressed in English, as immediate dominance rules for natural language (useful for example for programmers in the field of NLP—natural language processing), or visually as parse trees. All three representations are presented below.

1. An X Phrase consists of an optional specifier and an X-bar, in any order:

XP → (specifier), X′

XP XP

/ \ or / \

spec X' X' spec

2. One kind of X-bar consists of an X-bar and an adjunct, in either order:

(X′ → X′, adjunct)

Not all XPs contain X′s with adjuncts, so this rewrite rule is "optional".

X' X' / \ or / \ X' adjunct adjunct X'

3. Another kind of X-bar consists of an X (the head of the phrase) and any number of complements (possibly zero), in any order:

X′ → X, (complement...)

X' X' / \ or / \ X complement complement X

(a head-first and a head-final example showing one complement)

How the rules combine

The following diagram illustrates one way the rules might be combined to form a generic XP structure. Because the rules are recursive, there is an infinite number of possible structures that could be generated, including smaller trees that omit optional parts, structures with multiple complements, and additional layers of XPs and X′s of various types.

XP

/ \

spec X'

/ \

X' adjunct

/ \

X complement

|

head

Because all of the rules allow combination in any order, the left-right position of the branches at any point may be reversed from what is shown in the example. However, in any given language, usually only one handedness for each rule is observed. The above example maps naturally onto the left-to-right phrase order used in English.

Note that a complement-containing X' may be distinguished from an adjunct-containing X' by the fact that the complement has an X (head) as a sibling, whereas an adjunct has X-bar as a sibling.

A simple noun phrase

The noun phrase "the cat" might be rendered like this:

NP

/ \

Det N'

| |

the N

|

cat

The word the is a determiner (specifically an article), which at first was believed to be a type of specifier for nouns. The head is the determiner (D) which projects into a determiner phrase (DP or DetP). The word cat is the noun phrase (NP) which acts as the complement of the determiner phrase. More recently, it has been suggested that D is the head of the noun phrase.[citation needed]

Note that branches with empty specifiers, adjuncts, complements, and heads are often omitted, to reduce visual clutter. The DetP and NP above have no adjuncts or complements, so they end up being very linear.

In English, specifiers precede the X-bar that contains the head. Thus, determiners always precede their nouns if they are in the same noun phrase. Other languages use different word order.

A full sentence

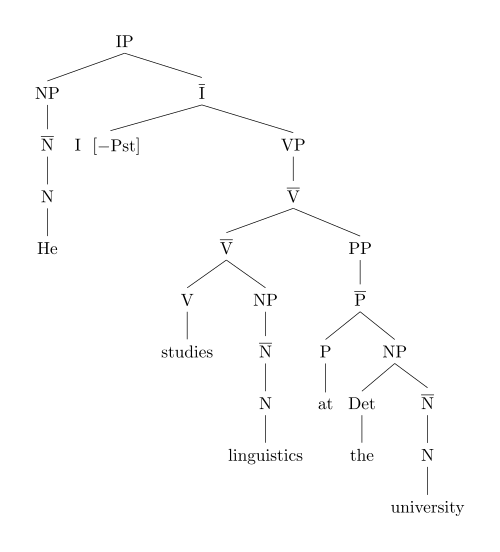

For more complex utterances, different theories of grammar assign X-bar theory elements to phrase types in different ways. Consider the sentence He studies linguistics at the university. A transformational grammar theory might parse this sentence as the following diagram shows:

The "IP" is an inflectional phrase. Its specifier is the noun phrase (NP) which acts as the subject of the sentence. The complement of the IP is the predicate of the sentence, a verb phrase (VP). There is no word in the sentence which explicitly acts as the head of the inflectional phrase, but this slot is usually considered to contain the unspoken "present tense" implied by the tense marker on the verb "studies".

A head-driven phrase structure grammar might parse this sentence differently. In this theory, the sentence is modeled as a verb phrase (VP). The noun phrase (NP) that is the subject of the sentence is located in the specifier of the verb phrase. The predicate parses the same way in both theories.

Substitution test

Evidence for the existence of X-bars may be provided by the various possibilities of substitution. For example, to the above sentence He studies linguistics at the university, someone may reply She does, also. Here the word does stands for the entire phrase studies linguistics at the university. However, had the reply been And she does at night-school, the word does would stand for just studies linguistics. This implies that significant constituents containing the verb exist at two levels; the constituent at the higher level here is named a verb phrase, and that at the lower level a V-bar (coming above the verb itself, which is studies).

Reduction

In 1981, Tim Stowell tried to derive X-bar theory from more general principles in his MIT thesis Origins of phrase structure, a pathbreaking but ultimately unsuccessful effort according to Andras Kornai and Geoffrey Pullum.[4] In the mid 1990s, there were two major attempts to deduce versions of X-bar theory from independent principles. Richard Kayne's theory of Antisymmetry derived X-bar theory from the assumption that there was a tight relation between structure and linear order; and Noam Chomsky's paper Bare Phrase Structure[5] attempted to eliminate labelling (i.e., bar-levels) from syntax and deduce their effects from other principles of the grammar.

Quantity of sentence structure

Theories of syntax that build on the X-bar schema tend to posit a large amount of sentence structure. The constituency-based, binary branching structures of the X-bar schema increase the number of nodes in the parse tree to the upper limits of what is possible. The result is highly layered trees (= "tall" trees) that acknowledge as many syntactic constituents as possible. The number of potential discontinuities increases, which increases the role of movement up the tree (in a derivational theory, e.g. Government and Binding Theory) or feature passing up and down the tree (in a representational theory, e.g. Lexical Functional Grammar). The analysis of phenomena such as inversion and shifting becomes more complex because these phenomena will necessarily involve discontinuities and thus necessitate movement or feature passing. Whether the large amount of sentence structure associated with X-bar schemata is necessary or beneficial is a matter of debate.

Endocentric structures only

When the X-bar schema was introduced and generally adopted into generative grammar in the 1970s, it was replacing a view of syntax that allowed for exocentric structures with one that views all sentence structure as endocentric. In other words, all phrasal units necessarily have a head in the X-bar schema, unlike the traditional binary division of the sentence (S) into a subject noun phrase (NP) and a predicate verb phrase (VP) (S → NP + VP), which was an exocentric division. In this regard, the X-bar schema was taking generative grammar one step toward a dependency-based theory of syntax, since dependency-based structures are incapable of acknowledging exocentric divisions. At the same time, the X-bar schema was taking generative grammar two steps away from a dependency-based understanding of syntactic structure insofar as it was allowing for an explosion in the amount of syntactic structure that the theory can posit. Dependency-based structures, in contrast, necessarily restrict the amount of sentence structure to an absolute minimum.

See also

References

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1970). Remarks on nominalization. In: R. Jacobs and P. Rosenbaum (eds.) Reading in English Transformational Grammar, 184-221. Waltham: Ginn.

- ^ Harris, Zellig (1951). Methods in structural linguistics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Jackendoff, Ray (1977). X-bar-Syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph 2. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ Kornai, Andras and Pullum, Geoffrey (1990) The X-bar theory of phrase structure. Language 66 24-50

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1994). "Bare Phrase Structure". MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics (5).