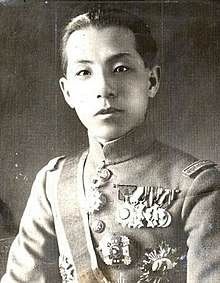

Zhang Xueliang

Zhang Xueliang | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | 張學良 |

| Nickname(s) | Young Marshal |

| Born | 3 June 1901 Taian, Liaoning, Qing Empire |

| Died | 15 October 2001 (aged 100) Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1915–1936 |

| Rank | General of the Army |

| Commands | Northeast Peace Preservation Forces |

| Battles / wars | |

| Spouse(s) | Yu Fengzhi (1897–1990) Gu Duanyu (1904–1983) Edith Chao (1912–2000) |

| Relations | Zhang Zuolin (father) Zhao Chungui (mother) |

Zhang Xueliang or Chang Hsueh-liang (later, Peter H. L. Chang) (3 June 1901[1] – 15 October 2001), nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern China after the assassination of his father, Zhang Zuolin (the "Old Marshal"), by the Japanese on 4 June 1928. He was an instigator of the 1936 Xi'an Incident, in which Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of China's ruling party, was arrested in order to force him to enter into a truce with the insurgent Chinese Communist Party and form a united front against Japan, which had occupied Manchuria. As a result, he spent over 50 years under house arrest, first in mainland China and then in Taiwan. He is regarded by the Chinese Communist Party as a patriotic hero for his role in the Xi'an Incident.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Biography

Early life

Born in Haicheng, Liaoning province in 1901, Zhang was educated by private tutors and, unlike his father, felt at ease in the company of westerners. He graduated from Fengtian Military Academy, was made a colonel in the Fengtian Army and appointed commander of his father's bodyguards in 1919. In 1921 he was sent to Japan to observe military maneuvers, where he developed a special interest in aircraft. Later he developed an air corps for the Fengtian Army, which was widely used in the battles that took place within the Great Wall during the 1920s. In 1922 he was promoted to Major General and commanded an army-sized force. Two years later he was also made commander of the air units. Upon the death of his father in 1928, he succeeded him as the leader of the Northeast Peace Preservation Forces (popularly "Northeast Army", 东北军 Dōngběi Jūn), which controlled China's northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang, Fengtian, and Jilin (Kirin).[8] In December of the same year he proclaimed his allegiance to the Kuomintang (KMT; Chinese Nationalist Party).

Warlord to republican general

The Japanese believed that Zhang Xueliang, who was known as a womanizer and an opium addict, would be much more subject to Japanese influence than was his father. On this premise, an officer of the Japanese Guandong Army therefore killed his father, Zhang Zuolin (the "Old Marshal"), by exploding a bomb above his train while it crossed under a railroad bridge. Surprisingly, the younger Zhang proved to be more independent and skilled than anyone had expected. With the assistance of Australian journalist William Henry Donald, he overcame his opium addiction and declared his support for Chiang Kai-shek, leading to the reunification of China in 1928.

He was given the nickname of 千古功臣; 'Hero of history' by PRC historians because of his desire to reunite China and rid it of Japanese invaders; and was willing to pay the price and become "vice" leader of China. (Not because it was good that he was supporting the Kuomintang.) In order to rid his command of Japanese influence, he had two prominent pro-Tokyo officials executed in front of the assembled guests at a dinner party in January 1929. It was a hard decision for him to make. The two had powers over the heads of others. Zhang was a fierce critic of many of the Soviet Union's policies, which served to undermine Chinese sovereignty, including its interference in Outer Mongolia. When he attempted to wrest control over a part of the Chinese Eastern Railway in Heilongjiang from the Soviets, he was beaten back by the Red Army.[9] At the same time, he developed closer relations with the United States.

In 1930, when warlords Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan attempted to overthrow Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang government, Zhang stepped in to support the Nanjing-based government against the Northern warlords in exchange for control of the key railroads in Hebei Province and the customs revenues from the port city of Tianjin. A year later, in the September 18 Mukden Incident, Japanese troops attacked Zhang's forces in Shenyang (Mukden) in order to provoke a full-on war with China, which Chiang did not want until his forces were stronger.[10] In accordance with this strategy, Zhang's armies withdrew from the front lines without significant engagements, leading to the effective Japanese occupation of Zhang's former northeastern domain.[11] There has been speculation that Chiang Kai-Shek wrote a letter to Zhang asking him to pull his forces back, but Zhang later stated that he himself issued the orders. Apparently Zhang was aware of how weak his forces were compared to the Japanese, and wished to preserve his position by retaining a sizeable army. Nonetheless, this would still be in line with Chiang's overall strategic standings. Zhang later traveled in Europe before returning to China to take command of the Encirclement Campaigns, first in Hebei-Henan-Anhui and later in the Northwest.

Xi'an incident

On 6 April 1936, Zhang met with CPC delegate Zhou Enlai to plan the end of the Chinese Civil War. KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek at the time took a non-aggressive position against Japan and considered the communists to be a greater danger to the Republic of China than the Japanese, and his overall strategy was to annihilate the communists before focusing his efforts on the Japanese.[10] He believed that "communism was a cancer while the Japanese represented a superficial wound." However, growing nationalist anger against Japan made this position very unpopular, leading to Zhang's action against Chiang known as the Xi'an incident.

On 12 December 1936, Zhang and Gen. Yang Hucheng kidnapped Chiang and imprisoned him until he agreed to form a united front with the communists against the Japanese invasion. After the negotiations, Chiang agreed to unite with the communists and drive the Japanese out of China. When Chiang was released, Zhang chose to return to the capital with him. However, once they were away from Zhang's loyal troops, Chiang had him put under house arrest. From there he was always watched and lived near the Nationalist capital, wherever it moved to.

Later life from 1949

In 1949 Zhang was transferred to Taiwan, where he remained under a loose house arrest for the next 40 years in a villa in Taipei's northern suburbs. He spent his time studying Ming dynasty literature, Manchu language and the Bible, receiving occasional guests and collecting Chinese fan paintings, calligraphy and other works of art by illustrious artists. A collection of more than 200 works, using his studio's name "Dingyuanzhai" (定远斋), was auctioned with tremendous success by Sotheby's on 10 April 1994. He and his wife, Edith Chao, became devout Christians and also regularly attended Sunday services at the Methodist chapel in Shilin, a Taipei suburb with Chiang Kai-Shek's family. After Chiang's death in 1975, his freedom was restored officially.

He immigrated to Honolulu, Hawaii, in 1993. There were numerous pleas for him to visit mainland China, but Zhang, claiming his political closeness with the KMT, declined. He died of pneumonia at the age of 100[a] at Straub Hospital in Honolulu,[2] and was buried in Hawaii.

In popular culture

- Zhang was portrayed by Andy Lau in a cameo appearance in the 1994 martial arts film Drunken Master II.

- Zhang was centrally featured in the 1981 Chinese film The Xi'an Incident (Xi'an Shibian), directed by Cheng Yin, with Zhang played by Jin Ange.

- A 2007 TV series on the Xi'an Incident was produced and aired in mainland China, with Zhang Xueliang being portrayed by Hu Jun.[citation needed]

- Zhang is a main figure in the American novel Soul Slip Peak (2013).

- The Peter H. L. Chang reading room at Columbia University's Butler Library is named after Zhang. The library hosts a collection of Zhang's papers.

- Beijing microbrewery Great Leap Brewing named its Little General IPA after Zhang.[12]

- A Chinese TV series titled 'Young Marshal' is based on Zhang's life.

See also

- Warlord era

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Sino-German cooperation (1911–1941)

Notes

- ^ Following the Chinese way of counting, his age is often given as 101.

References

- ^ According to other accounts, 1898 or 1900

- ^ a b Kristof, Nicholas D. (19 October 2001). "Zhang Xueliang, 100, Dies; Warlord and Hero of China". The New York Times. p. C13. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "Tribute for Chinese hero". BBC News. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 21 July 2002.

- ^ "Zhang Xueliang, Chinese military leader, died in Hawaii in 2001 at the age of 100". thinkfinity.org. 14 October 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "张学良老校长". neu.edu.cn. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "张学良先生今逝世 江泽民向其亲属发去唁电". chinanews.com. 15 October 2001. Retrieved 16 October 2001.

- ^ "伟大的爱国者张学良先生病逝 江泽民发唁电高度评价张学良先生的历史功绩". people.com.cn. 16 October 2001. Retrieved 17 October 2001.

- ^ Li, Xiaobing, ed. (2012). "Zhang Xueliang (Chang Hsueh-liang) (1901-2001)". China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 531.

- ^ Jeans, Roger B (1997). Democracy and Socialism in Republican China: The Politics of Zhang Junmai (Carsun Chang), 1906-1941. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 108.

- ^ a b "Chiang Kai-shek | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0674033388. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ McDonnell, Justin (23 July 2013). "Interview: Great Leap Brewery Founder Taps Into China's Thirst for a Good Microbrew". Asia Society. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

Further reading

External links

- Use dmy dates from October 2010

- 1901 births

- 2001 deaths

- People from Anshan

- Chinese Christians

- Chinese centenarians

- Converts to Christianity from Buddhism

- National Revolutionary Army generals from Liaoning

- Republic of China warlords from Liaoning

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Infectious disease deaths in Hawaii

- Children of national leaders

- Taiwanese people from Liaoning

- Chinese Civil War refugees

- People of the Northern Expedition

- People of the Central Plains War

- Chinese emigrants to the United States

- Taiwanese emigrants to the United States