Zinaida Reich

Zinaida Reich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Zinaida Nikolayevna Reich July 3, 1894 |

| Died | July 15, 1939 (aged 45) |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

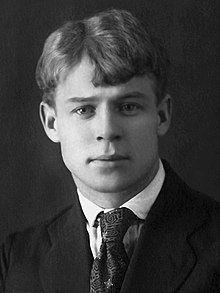

Zinaida Nikolayevna Reich (the last name also spelled Raikh or Raih; Template:Lang-ru; 3 July [O.S. 21 June] 1894 – 15 July 1939)[1] was a Russian actress and became one of the main stars of the Meyerhold Theatre until it was closed under Joseph Stalin. Reich married the poet Sergey Yesenin and had two children with him. After their divorce, she married the director Vsevolod Meyerhold. She is believed to have been murdered by the NKVD[citation needed] during the time of Great Purge.[2]

Family and early years

Zinaida Nikolayevna Reich was born in the village of Blizhniye Melnitsy near Odessa.[3] Her mother was Anna Ivanovna Viktorova, a Russian noblewoman and niece of a notable Russian linguist and archaeologist, Alexey Viktorov (Викторов, Алексей Егорович).[1] Her father was a russified German, Augustus Reich, who worked as a sailor and a railroad engineer.[1] In order to marry Anna, Reich (originally Roman Catholic) accepted Orthodox Christianity and was baptised as Nikolay Andreyevich Reich.[1] Augustus Reich was an early social democrat and had been twice politically exiled to the North of Russia prior to meeting Anna. As he continued his activity, during the Russian Revolution of 1905, the family was exiled from Odessa to Bendery.[1]

Zinaida Reich considered herself to be a hereditary proletarian. She studied in a gymnasium in Bendery but was expelled for her political activities before completing the eighth (last) grade.[4] She enrolled in the Kiev Higher Education Courses for Women, and in 1913 she became a member of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party.[5] In a year, she was arrested and spent two months in a prison. Her mother managed to arrange a certificate of secondary education for Reich so that she could continue her studies. Kiev would not allow her to study without a "certificate of political trustworthiness". Reich enrolled in Rayevsky Women Higher Education Courses in Saint Petersburg.

She also worked as a technical editor for Delo Naroda (People's Cause), a newspaper of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party. There she met the poet Sergey Yesenin, who at that time was influenced by the Party. Yesenin deserted the Russian Army in March 1917 following the February Revolution and settled in Saint Petersburg.[4]

Marriage to Sergey Yesenin

In spring 1917 Reich met Sergey Yesenin. The young people fell in love. They traveled to the White Sea and Russian North and got married in Kiriko-Ulitovskaya Church near Vologda on 4 August 1917.[1][4] After the wedding, the couple moved to Oryol, where her parents lived.[1][4] In September 1917 the couple returned to Saint Petersburg, where Reich worked for the People's Commissariat for Food (NarkomProd). In 1918 the People's Commissariat moved to Moscow and so did the couple. As Zinaida was pregnant, she moved to be with her parents in Oryol while Yesenin continued his literary career in Moscow.[4]

Reich returned to Moscow when their daughter Tatiana was one year old, but she and Yesenin quarreled. In February 1920 Reich gave birth to their son Konstantin, but the couple continued to live separately. At that time Reich lived in a shelter for mothers with infants. On 5 October 1921 Zinaida Reich and Sergey Yesenin were officially divorced.[4]

The story of the couple is known from the memoir Novel without Lies (1926)[6] (Роман без вранья) written by Yesenin's close friend, room-mate and allegedly homosexual lover[7][8] Anatoly Marienhof. Marienhof described Reich as a "crummy Jewish dame with fleshy lips on a face round as a dinner-plate". He wrote that Yesenin allegedly was upset when he saw his black-haired son, Konstantin. "No Yesenin had ever been black-haired", he allegedly said.[6] Reich had dark hair, which is genetically dominant over light hair.[9] Historians have doubted that Marienhof's description of Reich is accurate. She was of German-Russian ancestry and Russian Orthodox by faith.

Marriage to Meyerhold

Reich studied at the State Experimental Theatre Workshops, headed by famous theatrical director Vsevolod Meyerhold.[4] Meyerhold was 20 years older than she; at the time he had been married for 25 years to his wife Olga and had three daughters with her.[3] He ended up getting a divorce, and Reich and Meyerhold married in 1922.[5]

Yesenin and Reich had a relationship after her second marriage. The poet often broke into the house of Meyerholds demanding to see his former wife and children. Reich and Yesenin met secretly in her friend's apartment.[4] Their relations ended with the suicide of Yesenin on 23 December 1925.

Star of Meyerhold Theater

Reich worked as an actress and was featured as a star of the Meyerhold Theatre from 1923 until her death in 1939. According to the theatre critic N. Volkov:

"The works of Vsevolod Meyerhold of the 1920s and 1930s cannot be understood without Zinaida Reich... In all his productions, Meyerhold was building 'mise en scenes' to feature Zinaida Reich... If he was afraid that Zinaida would not manage her part, he would create beneficial 'mise en scenes' for her... Together with Meyerhold, Reich traveled his creative path: from experiments in biomechanics to deeper psychologism".[5]).

Meyerhold took the family name Meyerhold-Reich as a sign of their partnership.[4]

Not everyone accepted that a young actress with no experience had become the star of the famous theatre. According to Anatoly Marienhof, when Meyerhold had suggested that he would make Reich a great actress, Marienhof said he might as well invent electric lamps. Marienhof wrote that one needed no talent to become a famous actress – only Meyerhold as the husband and idiots as the public.[10] The actor Igor Ilyinsky was so upset that Reich received all the major roles that he left the Meyerhold Theater. Later, he revised his opinion of her acting talent and appreciated her.[5]

Murder

In the early 1930s, as Joseph Stalin repressed all avant-garde art and experimentation, the government declared Meyerhold's work as antagonistic and alien to the Soviet people. His theatre was closed down in January 1938. The ailing Constantin Stanislavski, then the director of an opera theatre (now known as Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre), invited Meyerhold to lead his company.

Stanislavski died in August 1938. Meyerhold directed his theatre for nearly a year until he was arrested in Leningrad on June 20, 1939. Twenty-five days later, his wife Zinaida Reich was found dying in their Moscow apartment on July 15, 1939.[11] It was believed that two unknown assailants broke into the Reich-Meyerhold apartment during the night of 14–15 July. They stabbed her 17 times, including through the eyes. Reich died from loss of blood the next morning. Her last words to her doctor were, "Leave me alone, I am dying." Reich had sent both her children out of the apartment that night, and nothing was taken from the apartment. Some historians believe that the murder was organized by the NKVD.[12][13][14][15]

Zinaida Reich was buried at Vagankovo Cemetery near the grave of her first husband Sergey Yesenin.[13] As Meyerhold was executed by the NKVD on 2 February 1940 after a confession from torture, the location of his remains is not known. Supporters erected a memorial to him at Reich's gravesite.[16]

The Moscow apartment was divided into two: one unit was given to Vardo Maximashvili[citation needed], an NKVD officer and an alleged lover of Lavrenty Beria[citation needed], the head of the NKVD. The other was given to Beria's personal chauffeur[citation needed]. Since the end of the Soviet Union, the whole apartment has been restored. It is now maintained and operated as the Meyerhold Museum.[13]

Reich's daughter Tatyana Yesenina (1918–92) became a notable writer. Her son Konstantin Yesenin (1920–86) became a journalist and a prominent football statistician.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Goltsova, Antonina. Сергей Есенин и Зинаида Райх (in Russian). RU. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ Зинаида Райх (in Russian). RU. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Zinaida Raikh". RU: Peoples Encyclopedia. 25 September 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Райх Зинаида". Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Yudina, Yekaterina. "Райх, Зинаида Николаевна". Encyclopedia Krugosvet. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Marienhof, Anatoly (1926). Novel without Lies (Роман без Вранья).

- ^ Blair, Fredrika (1986). Isadora: Portrait of the Artist as a Woman. McGraw-Hill. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-07-005598-8.

- ^ Leyland, Winston (1993). Gay Roots: Twenty Years of Gay Sunshine: an Anthology of Gay History, Sex, Politics, and Culture. Gay Sunshine Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-940567-12-2.

- ^ "РАЙХ Зинаида Николаевна". Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ Marienhof, Anatoly. Бессмертная трилогия (№2) – Мой век, моя молодость, мои друзья и подруги.

- ^ Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin: the Court of the Red Tsar. 2004; p. 323

- ^ Izgarshev, Igor (28 February 2001). Зинаида Райх: Гамлет в юбке (in Russian). RU. Argumenty i Fakty. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Загадка смерти Зинаиды Райх". Komsomolskaya Pravda. 14 November 2005. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Dovbnya, A. "Всеволод Мейерхольд и Зинаида Райх". Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Monastyrskaya, Anastasiya. Зинаида Райх: параллельные пути (in Russian). Women Saint-Petersburg. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ^ Bartsits, Oksana & Dursunov, Alexander (14 April 2003). Тайны Ваганьковского кладбища (in Russian). RU. Аргументы и Факты. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)