Kylix

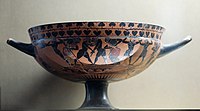

In the pottery of ancient Greece, a kylix (/ˈkaɪlɪks/ KY-liks, /ˈkɪlɪks/ KIL-iks; Ancient Greek: κύλιξ, pl. κύλικες; also spelled cylix; pl.: kylikes /ˈkaɪlɪkiːz/ KY-lih-keez, /ˈkɪlɪkiːz/ KIL-ih-keez) is the most common type of cup in the period, usually associated with the drinking of wine. The cup often consists of a rounded base and a thin stem under a basin. The cup is accompanied by two handles on opposite sides.

The inner basin is often adorned in the bottom so that as the liquid is consumed an image is revealed; this adornment is usually in a circular frame and called a tondo.[1] There are many variations of the kylikes, other cups available in the era include the skyphos, or the kantharoi.[2] Kylikes were also popular exports, being the most common pottery import from Attica found in Etruscan settlements.[3]

Etymology

[edit]

The Greek word kylix, meaning 'cup', could refer to both a drinking vessel as well as the cup shape of a flower. It is possibly related to the Latin word calix, also meaning 'cup', and may have originally been borrowed from a non-Indo-European language.[4] Kylix appears to in antiquity refer to the characteristic wide and short shape of the vessel and may have referred to many types of drinking vessels.[5]

Some types of kylikes have their own names with their own etymology. One such variety is komast cups, where komast refers to the name of the type of drunken figures painted on them, which is characteristic of the style. Another uniquely named type is a Siana cup, which is named after a site in Rhodes where it was originally found. The last major variety that has a specific name is the Little-Master cup, which is translated from German which references the small scale of the adornments on the cup.[5]

Purpose

[edit]

Kylikes are most famous for their association with symposiums and wine, where the set of kylikes could match the kraters, which are the mixing vessels for diluting wine.[2][3] These symposiums included various vessels for the preparation and drinking of wine and often were adorned with images of Dionysus and his worshippers.[6] However, the images in the tondo contained a variety of themes meant to surprise and amuse the party guest.

One such theme is that of sailing, often adorning mixing vessels in the late 6th century, ships and other maritime scenes were popular, as there were comparisons made between symposiums and sailing in literature of the time.[7] Other themes would include humorous designs, including on the base of the cup, such as the male genitals on the Bomford cup, a late 6th century kylix.[8]

At symposiums the process of mixing the wine was completed by a master of ceremonies then passed around by a young male slave.[6] The mixing of the wine and small drinking vessels are believed to possibly be an effort to allow a guest to enjoy his wine, but also avoid a drunken scandal, by encouraging moderation and lowering alcohol content.[9] Thus the shape of the kylix may have been an ideal shape for not only displaying art, but also for the reclined positions that men would sit or lay in while drinking at symposiums. The short broad shape allowed for reclined drinking with minimal risk of spilling.[10] The handles allowed the guests to play kottabos,[3] where a guest would put their right index finger into one of the handles and attempt to fling the last of their wine into a target, often a container on a pedestal or floating in a pool, in order to win a prize.[10]

Subtypes

[edit]

There are many types of kylix that have been defined by archaeologists, often denoting a regional variance or chronological difference.[5] One of the major features of early cups is if they have an offset lip or not, the lack of an offset lip means that if one were to place the cup on a flat surface the lip would be parallel to the surface the cup is set on rather than angled in some way.

Of the majorly chronological types there are types A, B and C. Type A developed in the late 6th century BCE and fade out of production by the early 5th century. This type is characterized by a smooth profile, lack of an offset lip and a wide, short stem. These cups also featured both red and black figure art, sometimes on the same cup called bilingual kylix.[5][9][11]

Type B is very reminiscent of Type A, except the stems are thinner and has a more curved joining from the basin to the stem of the cup.[5] This type is the most common found in Etruscan tombs.[3]

Type C is less common than types A and B and sometimes has an offset lip and can have carving or molding on the base of the stem. However, they are less decorative than previous types and are often solid black in color and may only be decorated in the tondo.[5]

For the stylistic and locational types continue to be definitions based on the presence of an offset lip as well as the types of decorations present on the cups. One such type is the komast cup developed in Athens and inspired by Corinthian pottery; it is defined by a narrow lip and sharp offset paired with a short, flared stem. This type is also defined with a decoration of drunken parties portrayed on the outside of the cup which grants this style its name.[5][12]

Another type is the Siana cup; this style is known for its tall feet and lips when compared to the komast cups. They are also defined with a decorated tondo and are decorated in a style reminiscent of eastern Greek traditions.[5] Their decorations can be large when compared to those of other types, often covering from foot to lip, or having layers of decoration to cover the outside of the cup. When compared to Little-Master cup, their basins are deeper and have a less defined lip.[13]

Little-Master cups are named for the small details in their decorative elements, they are characterized by half globe basins and tall thin stems.[13] They can often be divided into two more specific styles, lip cups and band cups. Lip cups have a more offset lip, often focusing on the lower parts of the cup. Band cups on the other hand are mostly black save for a band of decoration all around the cup often containing images of people.[5] Stemless cups are known for their lack of stem and most surviving examples are plain black and lacking decoration.[5]

Decoration and construction

[edit]

Kylikes are most famous for their adornments; adorned kylikes were part of a set used for special occasions such as a symposium, the most common kylikes were of a solid color without adornment.[2] If present, the tondo contains either black-figure or red-figure styles of the 6th and 5th century BC, and the outside was also often painted;[2] an example of a tondo can be seen to the left. Black glaze type B kylikes appear to have been a popular export to Etruscan settlements and are not as commonly found in the Athens area, where it is believed they developed. This may suggest that these were made with the intention of exporting these kylikes.[3]

Some of the earliest designs found on kylix include spiked flower designs and whorled shells. These designs could be paired with chevrons or dot designs between the whorls or spiked flowers to fill space, although this was more common with whorled designs.[15] Later designs included the presence of roosters, which is believed to be reminiscent of the fact that an older man may gift a young man a rooster as a sign of love. It is debated if this is the reasoning behind the presence of roosters as cock fighting was also a common form of entertainment at the time, many other common symbols seen in the art of kylikes are similarly debated in meaning.[13] At other times the meaning is less debated, as in some kylikes there are sexually explicit images portrayed[13] as were scenes of parties.[12] Many kylikes also drew from mythological stories in their art.[16] A few of the more famous painters of the time were Onesimos, Makron, and Douris.[17]

Ridged varieties of kylix have much more variety in shape and appear to have less consistent qualities of craftsmanship than those with smooth profiles. This may be due to smooth profiled kylikes being intended for more elite consumers who could pay for more carefully made and decorated pieces. Kylikes that had been polished or had their pores filled with slip made better drinking vessels as they did not absorb the liquid they contained. Most kylikes were made of ceramics however, but it is believed they were modeled after metal drinking vessels of the elite.[18]

Famous pieces

[edit]Individual kylikes with articles include:

- Arkesilas Cup, very unusual because it shows a then-living political figure, Arkesilaos II, king of Kyrene (died 550 BC). It is dated to about 565/560 BC, and is now in Paris.

- Dionysus Cup, famous for its painting, 540–530 BC. It is one of the masterpieces of the Attic black-figure potter Exekias and one of the most significant works in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich.[19]

- Berlin Foundry Cup, a red-figure kylix from the early 5th century BC. It is the name vase of the Attic vase painter known conventionally as the Foundry Painter. Its most striking feature is the exterior depiction of activities in an Athenian bronze workshop or foundry. It is an important source on ancient Greek metal-working technology.

- Brygos cup of Würzburg, an Attic red-figure kylix from about 480 BC. It was made by the Brygos potter and painted by the man known as the Brygos Painter. Its symposium scenes are some of the best-known images of Greek pottery.

See also

[edit]![]() Media related to Kylixes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kylixes at Wikimedia Commons

References

[edit]- ^ Kylix (Drinking Cup), Art Institute Chicago, retrieved 2023-05-19

- ^ a b c d "2006.35.T, Attic Kylix". Department of Classics. 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e Steiner, Ann; Neils, Jenifer (2018-12-19). "An Imported Attic Kylix from the Sanctuary at Poggio Colla". Etruscan Studies. 21 (1–2): 98–145. doi:10.1515/etst-2018-0010. ISSN 2163-8217. S2CID 194911397.

- ^ "kylix | Etymology, origin and meaning of kylix by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Cups and other drinking vessels". www.carc.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ a b Art, Authors: Department of Greek and Roman. "The Symposium in Ancient Greece | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ "Terracotta kylix: eye-cup (drinking cup) | Greek, Attic | Archaic". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ Osborn, Robin (1998). Archaic and classical Greek art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9780192842022. OCLC 40162410.

- ^ a b Naglak, Matthew (2010-01-01). "Turning the Cup: Thematic Balance in the Greek Symposium". Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal. 11 (1).

- ^ a b Museum, Seattle Art (2019-10-11). "Object of the Week: Kylix". SAMBlog. Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- ^ Mack, Charles R. (March 2016). "An Eye-Cup Fragment by the Amasis Painter in South Carolina". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 35 (3): 205–215. doi:10.1086/686706. ISSN 0737-4453. S2CID 192890825.

- ^ a b Miller, Margaret (2007). Csapo, Eric (ed.). The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond from Ritual to Drama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83682-1.

- ^ a b c d Padgett, J. Michael (2002). "Objects of Desire: Greek Vases from the John B. Elliott Collection". Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University. 61: 37–48. doi:10.2307/3774766. ISSN 0032-843X. JSTOR 3774766.

- ^ "Running Warrior". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Wace, A. J. B. (November 1957). "Part V. The Chronology of Late Helladic IIIB". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 52: 220–223. doi:10.1017/s0068245400012983. ISSN 0068-2454. S2CID 163305772.

- ^ Timeline of Art History Archived 2008-03-02 at the Wayback Machine, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Retrieved on 2008-03-18.

- ^ Ancient Greek Pottery Archived 2008-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Young Aggressive Sincere Organized and United, 2005-01-10.

- ^ "Aegean Bronze Age civilizations", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2003, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t000544, retrieved 2023-06-06

- ^ Inventory number 8729 (formerly 2044); evaluation of worth by John Boardman, Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen. Mainz 1977, p. 64 and Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei. Stuttgart 2002, p. 121