Pedal point

In music, a pedal point (also pedal note, organ point, pedal tone, or pedal) is a sustained tone, typically in the bass, during which at least one foreign (i.e. dissonant) harmony is sounded in the other parts. A pedal point sometimes functions as a "non-chord tone", placing it in the categories alongside suspensions, retardations, and passing tones. However, the pedal point is unique among non-chord tones, "in that it begins on a consonance, sustains (or repeats) through another chord as a dissonance until the harmony", not the non-chord tone, "resolves back to a consonance".[2]

Pedal points "have a strong tonal effect, 'pulling' the harmony back to its root".[2] Pedal points can also build drama or intensity and expectation. When a pedal point occurs in a voice other than the bass, it is usually referred to as an inverted pedal point[3] (see inversion). Pedal points are usually on either the tonic or the dominant (fifth note of the scale) tones. The pedal tone is considered a chord tone in the original harmony, then a nonchord tone during the intervening dissonant harmonies, and then a chord tone again when the harmony resolves. A dissonant pedal point may go against all harmonies present during its duration, being almost more like an added tone than a nonchord tone, or pedal points may serve as atonal pitch centers.

The term comes from the organ for its ability to sustain a note indefinitely and the tendency for such notes to be played on an organ's pedal keyboard. The pedal keyboard on an organ is played by the feet; as such, the organist can hold down a pedal point for lengthy periods while both hands perform higher-register music on the manual keyboards.

Types

[edit]A double pedal is two pedal tones played simultaneously. An inverted pedal is a pedal that is not in the bass (and often is the highest part.) Mozart included numerous inverted pedals in his works, particularly in the solo parts of his concertos. An internal pedal is a pedal that is similar to the inverted pedal, except that it is played in the middle register between the bass and the upper voices.

A drone differs from a pedal point in degree or quality. A pedal point may be a nonchord tone and thus required to resolve, unlike a drone, or a pedal point may simply be a shorter drone, a drone being a longer pedal point.

Use in classical music

[edit]There are numerous examples of pedal points in classical music. Pedal points often appear in early baroque music "alla battaglia", notably prolonged in Heinrich Schütz's Es steh Gott auf (SWV 356) and Claudio Monteverdi's Altri canti di Marte.[4]

In Henry Purcell's "Fantasia upon One Note" for a consort of viols, a tenor viol sustains a C throughout, while the other viols weave increasingly elaborate counter-melodies around it:

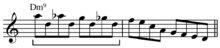

Pedal points are often found near the end of fugues "... to reestablish the tonality of the composition after it has become clouded by the numerous modulations and digressions along the way within the middle entries of the subject and answer and in the connecting episodes".[5] Fugues often conclude with figures written over a bass pedal point:[6]

Pedal points are also used in other polyphonic compositions to strengthen a final cadence, signal important structural points in the composition, and for their dramatic effect.

Pedal points are somewhat problematic on the harpsichord, which has only a limited sustain capability. Often the pedal note is simply repeated at intervals. A pedal tone can also be realized with a trill; this is particularly common with inverted pedals. Another method of producing a pedal point on the harpsichord is to repeat the pedal point note (or its octave) on every beat. The rarely seen pedal harpsichord, a harpsichord with a pedal keyboard, makes it easier to perform repeated bass notes on the harpsichord, since both hands are still free to play on the upper manual keyboards.

With the development of the piano, composers began exploring the potential of a pedal-point in creating mood and atmosphere. An example is the inverted pedal that pervades the right hand part of the piano accompaniment in Schubert's song Erlkönig:

According to Eugene Narmour (1987, p. 101) "There is no instrument on which a pedal point sounds better than the piano (with its ready-made damper mechanism), and, safe to say, no composer more fond of harmonic pedals than Chopin."[7] An example is the Prelude in D♭, Op. 28, No. 15, (the "Raindrop Prelude") which, like the Purcell, features one repeated note throughout. The piece is in ternary form, with its serene outer "A" sections contrasting the brooding middle "B" section:

In this prelude, the repeated bass A♭ that pervades the outer section becomes, through an enharmonic change, a G♯ in the minor key middle section, where it moves from the bass to the top part. There are other examples of piano music where a single note pervades almost the entire piece: a persistent B♭ features in both Debussy's piano prelude "Voiles" and "Le Gibet" from Ravel's Gaspard de la Nuit.

The term "pedal point" is also used to describe a bass note that is held for a long period in orchestral music, as in the symphonies of Jean Sibelius. Pedal points for orchestral music are often performed by the double basses with the bow, which creates a sustained, organ-like bass tone underneath the changing harmonies in the upper voices. The closing section of the third movement of Johannes Brahms's Ein Deutsches Requiem, "Herr, lehre doch mich" (bars 173–208), features a sustained timpani roll on D natural for over two minutes until resolving in the final chord:

Ernest Newman (1947, p. iii) wrote of the "mixed reception" given to the Requiem, particularly this movement, which "was greeted with many expressions of disapproval; the continual pedal point—intensified by the too vigorous work of the drummer".[8]

Use in opera

[edit]The openings of the first two operas of Wagner's cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen ("The Ring of the Nibelung") feature pedal notes. The prelude to Das Rheingold features an E♭ pedal tone in the bass for 162 bars:

Robert Donington (1963, p. 35)[9] says: "The Ring opens quietly, but with an effect which in the context of harmonized music is apparently unique. For a very long passage there is not only no modulation but no change of chord. A chord of E♭ major builds up: first the tonic sounds in the abysmal depths; next a fifth is added; then an arpeggio movement on the complete triad, calm but swelling, an embryonic motive ... But still the chord does not change ... A sense of timelessness sets in."

By contrast, the stormy prelude to Die Walküre features an inverted pedal: the sustained tremolos in the upper strings offset the melodic and rhythmic activity in the 'cellos and basses:

Alban Berg’s expressionist opera Wozzeck makes subtle use of a pedal tone in Act 3, scene 2, when the jealous, put-upon soldier Wozzeck murders his unfaithful wife, Marie. Douglas Jarman (1989, p38) describes the powerful dramatic effect of this episode:[10] "Marie and Wozzeck are walking through the wood. Anxious, Marie tries to hurry on but Wozzeck detains her. A disjointed, sinister conversation follows until, as the moon rises, blood-red, Wozzeck draws a knife. A long crescendo begins as the note B natural, which has been present as a subdued pedal point throughout the scene, is now taken up by the kettledrums. Wozzeck plunges the knife into Marie’s throat."

Use in jazz and popular music

[edit]Examples of jazz tunes which include pedal points include Duke Ellington's "Satin Doll"" (intro), Stevie Wonder's "Too High" (intro), Miles Davis's "On Green Dolphin Street", Bill Evans's "34 Skidoo", Herbie Hancock's "Dolphin Dance" from his Maiden Voyage album, Pat Metheny's "Lakes" and "Half Life of Absolution", and John Coltrane's "Naima".[11] The latter, from the album Giant Steps, has the notation "E♭ pedal" to instruct the bass player to play a sustained pedal. Jazz musicians also use pedal points to add tension to the bridge or solo sections of a tune. In an ii-V-I progression, some jazz musicians play a V pedal note under all three chords, or under the first two chords.

Rock guitarists have used pedal points in their solos. The progressive rock band Genesis often used a "pedal-point groove",[12] in which the "bass remains static on the tonic as chords move above the bass at varying speeds", with the Genesis songs "Cinema Show" and "Apocalypse in 9/8"[12] being examples of this.[13] "By the late 1970s and early 1980s, pedal-point grooves such as this had become a well-worn cliché of progressive rock as they had of funk (James Brown’s "Sex Machine"), and were already making frequent appearances in more commercial styles such as stadium rock (Van Halen’s 'Jump') and synth-pop (Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s 'Relax')."[13]

Film composers use pedal points to add tension to thrillers and horror films. In the Hitchcock thriller film North by Northwest, Bernard Herrmann "uses the pedal point and ostinato as techniques to achieve tension", resulting in a dissonant, dramatic effect. In one scene, "The Phone Booth", Herrmann "uses the timpani playing a low pedal B-flat to create a sense of impending doom", as one character is arranging for another character's murder.[14] Other notable examples from similar genres are the music for the opening title of the TV series "Sherlock" by David Arnold and Michael Price, and one of the main themes of Interstellar by Hans Zimmer: "[...] to sustain a dominant pedal at length as this theme does gives an impression of a prolonged avoidance of resolution. Indeed, given the enormous length of time that elapses during Cooper’s absence, this is an entirely appropriate sentiment.".[15]

In small combo jazz or jazz fusion groups, the double bass player or Hammond organist may also introduce a pedal point (usually on the tonic or the dominant) in a tune that does not explicitly request a pedal point, to add tension and interest. Thrash metal in particular makes abundant use a muted low E string (or lower, if other tunings are used) as a pedal point.

Other examples include The Supremes' "You Keep Me Hangin' On" (chorus: octave E's against A, G, and F major chords) and John Denver's "The Eagle And The Hawk" (intro: top two guitar strings, B & E, against B, A, G, F, and E major chords).[16] Also, Tom Petty's "Free Falling" and Goo Goo Dolls' "Name".[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zinn, David (1981). The Structure & Analysis of the Modern Improvised Line, p. 118. ISBN 978-0-935016-03-1.

- ^ a b Frank, Robert J. (2000). "Non-Chord Tones". Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Theory on the Web, Southern Methodist University.

- ^ a b c Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 99. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Gerald Drebes: "Schütz, Monteverdi und die „Vollkommenheit der Musik“ – „Es steh Gott auf“ aus den „Symphoniae sacrae“ II (1647)". In: "Schütz-Jahrbuch", Jg. 14, 1992, p. 25–55, h. 37–40, online: "Gerald Drebes - 2 Aufsätze online: Monteverdi und H. Schütz" (in German). Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ^ "The Fugue", an outline of the substantials of a fugue based on Hugo Norden's Foundation Studies in Fugue.

- ^ Smith, Timothy A. (1996). "Anatomy of a Fugue".

- ^ Narmour, E. (1987) "Melodic structuring of harmonic dissonance" in Samson, J. (ed.) Chopin Studies. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Newman, E. (1947) preface to the vocal score of Brahms Ein Deutsches Requiem, reprinted in the 1999 edition. London, Novello and Co. Ltd.

- ^ Donington, R. (1963) Wagner's "Ring" and its Symbols. London, Faber.

- ^ Jarman, D (1989) Alban Berg Wozzeck. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Rawlins, Robert (2005). Jazzology: The Encyclopedia of Jazz Theory for All Musicians, p. 132. ISBN 0-634-08678-2.

- ^ a b Spicer, Mark S.; Rudolph, John (2010). Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music. United States of America: The University of Michigan Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1.

- ^ a b "Composition And Experimentation In British Rock 1967–1976", Philomusica on-line.

- ^ "A Case Study of the Bernard Herrmann Style", p. 2, Hitchcock.TV.

- ^ Richards, Mark (February 18, 2015). "Oscar Nominees 2015, Best Original Score (Part 5 of 6): Hans Zimmer's Interstellar". Film Music Notes. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p. 77. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- ^ Stephenson (2002), p. 81.