Jagera people

The Jagera people, also written Yagarr, Yaggera, Yuggera, and other variants, are the Australian First Nations people who speak the Yuggera language. The Yuggera language which encompasses a number of dialects was spoken by the traditional owners of the territories from Moreton Bay to the base of the Toowoomba ranges including the city of Brisbane. There is debate over whether the Turrbal people of the Brisbane area should be considered a subgroup of the Jagera or a separate people.[2][3]

Language

[edit]Yuggera belongs to the Durubalic subgroup of the Pama–Nyungan languages, and is sometimes treated as the language of the Brisbane area.[4] However, Turrbal is also sometimes used as the name for the Brisbane language or the Yugerra dialects of the Brisbane area.[5][6][7][8] The Australian English word "yakka" (loosely meaning "work", as in "hard yakka") came from the Yuggera language (yaga, "strenuous work").[9]

According to Tom Petrie, who provided several pages listing words and placenames in the languages spoken in the area of Brisbane (Mianjin),[10] yaggaar was the local word for "no".[11] (The word for "no" in Aboriginal languages was often an ethnonymic marker of difference between Aboriginal groups.)[11] Mianjin is a Yuggera/Turrbal word meaning "spike place" or "tulip wood". It was used for the area now covered by Gardens Point and the Brisbane central business district.[12][10] The Yuggera word for the Aboriginal people of Brisbane was Miguntyun.[13]

Ludwig Leichhardt recorded the name for the land holding area from Gardens Point to Breakfast Creek as Megandsin or Makandschin.[14]

Country

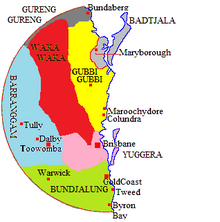

[edit]The precise territorial boundaries of the Jagera are not clear.[15][16] Norman Tindale defined the "Jagara" (Jagera) lands as encompassing the area around the Brisbane River from the Cleveland district west to the dividing range and north to the vicinity of Esk.[5] According to Watson, the "Yugarabul tribe" (Jagera) inhabited the territories from Moreton Bay to Toowoomba to the west, extending almost to Nanango in the northwest.[17] He also describes their territory as "the basins of the Brisbane and Caboolture Rivers" and states that a sub-group of the Yugarabul was the "Turaubul" (Turrbal) people whose territory included the site of the modern city of Brisbane.[2] According to Steele, the territory of the "Yuggera people" (Jagera) extended south to the Logan river, north almost to Caboolture and west to Toowoomba.[18] However, he considered that Turrbal speakers covered much of Brisbane from the Logan river to the Pine river.[19] Ford and Blake state that the Jagera and Turrbal were distinct peoples, the Jagera generally living south of the Brisbane river and the Turrbal mostly living north.[16]

At the time of European settlement, the Jagera people comprised local groups each of which had a specific territory.[2] The European names for the locality groups, sometimes called clans, of the Brisbane area include the Coorpooroo, Chepara, Yerongpan and others.[19][17]

Jagera territory adjoined that of the Wakka Wakka and the Gubbi Gubbi (also written Kabi Kabi or Gabi Gabi) to the north, and that of the Yugambeh and the Bundjalung people to the south.[20]

Native title

[edit]Descendants of both the Jagera (Yugara) and the Turrbal consider themselves traditional custodians of the land over which much of Brisbane is built.[21] Native claim applications were lodged respectively by the Turrbal in 1998 and the Jagera in 2011, and the two separate claims were combined in 2013.[21] In January 2015, Justice Christopher Jessup for the Federal Court of Australia, in Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2),[22] rejected the claims on the basis that under traditional law, which was now lacking, none of the claimants would be considered to have such a land right.[21] The decision was appealed before the full bench of the Federal Court, which on 25 July 2017 rejected both appeals, confirming the 2015 decision that native title does not exist in the greater Brisbane area.[23][24][25][26]

An Indigenous land use agreement (ILUA) was signed over the site of the historic 1843 Battle of One Tree Hill, now known as Table Top Mountain, when the warrior Multuggerah from the Ugarapul tribe and a group of men ambushed and won a battle with settlers in the area. The ILUA was signed between Toowoomba City Council and a body representing the "Jagera, Yuggera and Ugarapul people" as the traditional owners of the area, in 2008 (Ilua 2008).

Variant names and spellings

[edit]- Jagarabal (jagara = no)

- Jergarbal

- Yagara

- Yaggara

- Yuggara

- Yugg-ari

- Yackarabul

- Turubul (language name)

- Turrbal

- Turrubul

- Turrubal

- Terabul

- Torbul

- Turibul

- Yerongban

- Yeronghan

- Ninghi

- Yerongpan[5]

- Biriin[27]

Place names

[edit]

- Meebatboogan, Mount Greville, Moogerah Peaks National Park

- Cooyinnirra, Mount Mitchell, Main Range National Park

- Booroongapah, Flinders Peak, Flinders Peak Group

- Ginginbaar, Mount Blaine, Flinders Peak Group

Notable people

[edit]- Multuggerah, 19th-century warrior

- Hon. Neville Bonner, former Australian senator, Jagera elder[28]

- Jeanie Bell, Australian linguist[29]

- Faye Carr, 2017 National NAIDOC Awards Winner Female Elder of the Year[30][31][32]

- Latia Schefe, 2017 National NAIDOC Awards Winner Youth of the Year[30][33][32]

- Susan McCarthy, originally Bunjoey, daughter of Moonpago[34][35][a]

- Uncle Desmond Sandy, Aunty Ruth James and Aunty Pearl Sandy, claimants in the 2015 native title case[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bunjoey was the original informant for the stories in Edin Bell's Legends of the Coochin Valley. Bell identified the local tribe around Wallaces Creek, as Ugarapul, a form that has not gained acceptance in later Aboriginal studies.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Watson 1944.

- ^ a b c Watson 1944, pp. 4–5.

- ^ AustLII 2015, paragraphs 36-37, 40-43.

- ^ Dixon, Ramson & Thomas 2006, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Tindale 1974, p. 169.

- ^ Steele 2015, pp. 85, 121.

- ^ Dixon 2002, p. xxxiv.

- ^ Bowern 2013, pp. lix, lxiv.

- ^ Dixon, Ramson & Thomas 2006, p. 209.

- ^ a b Petrie & Petrie 1904, pp. 315–319.

- ^ a b Petrie & Petrie 1904, p. 319.

- ^ Steele 2015, pp. 122, 129.

- ^ The Queenslander 1934, p. 13.

- ^ Jefferies 2013, p. 640.

- ^ AustLII 2015, paragraphs 35-37.

- ^ a b Ford & Blake 1998, p. 11.

- ^ a b Crump 2015.

- ^ Steele 2015, p. xiv.

- ^ a b Steele 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Steele 2015, p. 46, 85.

- ^ a b c Riga 2015.

- ^ a b AustLII 2015.

- ^ Singleton & Testro 2017.

- ^ CCW 2017.

- ^ Carseldine 2017.

- ^ NNTT 2015.

- ^ Tindale 1974, pp. 169, 171.

- ^ Rolls & Johnson 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Russo 2015, p. 215.

- ^ a b Queensland Govt 2017.

- ^ Morelli 2017.

- ^ a b Zhou 2017.

- ^ ABC News 2017.

- ^ The Courier-Mail 1947, p. 2.

- ^ The Telegraph 1936, p. 11.

Sources

[edit]- "Aboriginal Language". The Queenslander. Brisbane. 18 January 1934. p. 13. Retrieved 27 October 2017 – via Trove.

- Bell, Edin (1946). Legends of the Coochin Valley. Bunyip Press – via Trove.

- Bowern, Claire, ed. (2013). The Oxford Guide to Australian Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198824978.

- Carseldine, Amy (18 September 2017). "Negative determination of native title over Brisbane upheld". Crown Law (Queensland Govt). Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Crump, Des (16 March 2015). "Aboriginal languages of the Greater Brisbane Area". Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages. State Library of Queensland. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Dixon, Robert M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.

- Dixon, R. M. W.; Ramson, W.S.; Thomas, Mandy (2006). Australian Aboriginal Words in English: Their Origin and Meaning (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-54073-4.

- Ford, Roger; Blake, Thom (1998). Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Queensland: an annotated guide to ethno-historical sources. Woolloonbabba, Qld: The Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research Action. ISBN 1876487003.

- Erdos, Renee (1967). Leichhardt, Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig (1813–1849) (2: 1788–1850 I-Z ed.). Melbourne: Australian National University. pp. 102–104. ISBN 0-522-84236-4 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- "Full Federal Court determines native title does not exist over a large part of greater Brisbane". Corrs Chambers Westgarth. 26 September 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Howitt, A. W. (Alfred William) (1904). The native tribes of South-East Australia. Robarts – University of Toronto. London: Macmillan – via Internet Archive.

- Jefferies, Anthony (2013). "Leichhardt: His contribution to Australian Aboriginal linguistics and ethnography 1843-44". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture. 7 (2): 633–652. ISSN 1440-4788.

- "Indigenous land use agreement signed in Toowoomba". National Native Title Tribunal. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Last of Her Tribe-- Ugaraphul Princess Buried At Coochin". The Telegraph. Brisbane. 30 May 1936. p. 11. Retrieved 19 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Meadows, Michael (2001). Voices in the Wilderness: Images of Aboriginal People in the Australian Media. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31566-4.

- "Mills takes out Person of the Year at NAIDOC Awards". ABC News. 2 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Morelli, Laura (3 July 2017). "This Yuggera Grandmother of 47 scores Female Elder of the year award at NAIDOC". NITV. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Petrie, Constance Campbell; Petrie, Tom (1904). Tom Petrie's reminiscences of early Queensland (dating from 1837). Cornell University Library. Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & co. – via Internet Archive.

- "QCD2015/001 – Yugara/YUgarapul People and Turrbal People". National Native Title Tribunal. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "Queenslanders Honoured at National NAIDOC Awards". Queensland Government. 1 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Riga, Rachel (28 January 2015). "Turrbal-Yugara native title claim over Brisbane rejected". ABC News. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Rolls, Mitchell; Johnson, Murray (2010). Historical Dictionary of Australian Aborigines. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-87475-6.

- Russo, Katherine E. (2015). "Semantic Change: Intersubjectivity and Social Knowledge in the Sydney Morning Herald". In Calabrese, Rita; Chambers, J. K.; Leitner, Gerhard (eds.). Variation and Change in Postcolonial Contexts. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 209–227. ISBN 978-1-443-88493-8.

- Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2015] FCA 15 (27 January 2015), Federal Court (Australia).

- Singleton, Scott; Testro, Nick (26 July 2017). "Full Federal Court confirms native title does not exist over greater Brisbane". King & Wood Mallesons. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Steele, John Gladstone (2015). Aboriginal Pathways: in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-702-25742-1.

- "This Week'S Book Reviews". The Courier-Mail. No. 3168. Brisbane. 18 January 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 19 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Watson, F. J. (1944). "Vocabularies of four representative tribes of South Eastern Queensland: with grammatical notes thereof and some notes on manners and customs, also, a list of Aboriginal place names and their derivations". Journal of The Royal Geographical Society of Australasia. 48 (34). Brisbane. OCLC 682056722. Retrieved 31 October 2017 – via Trove.

- Zhou, Naaman (1 July 2017). "Naidoc awards: Dianne Ryder, Ollie George and Patty Mills among winners". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 July 2017.