Synthon

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2015) |

In retrosynthetic analysis, a synthon is a hypothetical unit within a target molecule that represents a potential starting reagent in the retroactive synthesis of that target molecule. The term was coined in 1967 by E. J. Corey.[1] He noted in 1988 that the "word synthon has now come to be used to mean synthetic building block rather than retrosynthetic fragmentation structures".[2] It was noted in 1998[3] that the phrase did not feature very prominently in Corey's 1981 book The Logic of Chemical Synthesis,[4] as it was not included in the index. Because synthons are charged, when placed into a synthesis an uncharged form is found commercially instead of forming and using the potentially very unstable charged synthons.

Example

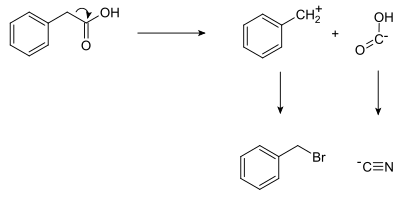

[edit]In planning the synthesis of phenylacetic acid, two synthons are identified: a nucleophilic "COOH−" group, and an electrophilic "PhCH2+" group. Of course, both synthons do not exist by themselves; synthetic equivalents corresponding to the synthons are reacted to produce the desired reactant. In this case, the cyanide anion is the synthetic equivalent for the COOH− synthon, while benzyl bromide is the synthetic equivalent for the benzyl synthon.

The synthesis of phenylacetic acid determined by retrosynthetic analysis is thus:

- Ph−CH2−Br + Na+[C≡N]− → Ph−CH2−C≡N + NaBr

- Ph−CH2−C≡N + 2 H2O → Ph−CH2−C(=O)−OH + NH3

where Ph stands for phenyl.

- C2 synthons - acetylene, acetaldehyde

- -C2H4OH synthon - ethylene oxide

- carbocation synthons - alkyl halides

- carbanion synthons - Grignard reagents, organolithiums, substituted acetylides

Alternative use in synthetic oligonucleotides

[edit]This term is also used in the field of gene synthesis—for example "40-base synthetic oligonucleotides are built into 500- to 800-bp synthons".[5]

Carbocationic synthons

[edit]

Many retrosynthetic disconnections important for organic synthesis planning use carbocationic synthons. Carbon-carbon bonds, for example, exist ubiquitously in organic molecules, and are usually disconnected during a retrosynthetic analysis to yield carbocationic and carbanionic synthons. Carbon-heteroatom bonds, such as those found in alkyl halides, alcohols, and amides, can also be traced backwards retrosynthetically to polar C-X bond disconnections yielding a carbocation on carbon. oxonium and acylium ions are carbocationic synthons for carbonyl compounds such as ketones, aldehydes and carboxylic acid derivatives. An oxonium-type synthon was used in a disconnection en route[clarification needed] to the hops ether[clarification needed],[6] a key component of beer (see fig.1). In the forward direction, the researchers used an intramolecular aldol reaction catalyzed by titanium tetrachloride to form the tetrahydrofuran ring of hops ether.

Another common disconnection that features carbocationic synthons is the Pictet-Spengler reaction. The mechanism of the reaction involves C-C pi-bond attack onto an iminium ion, usually formed in situ from the condensation of an amine and an aldehyde. The Pictet-Spengler reaction has been used extensively for the synthesis of numerous indole and isoquinoline alkaloids.[7]

Carbanion alkylation is a common strategy used to create carbon-carbon bonds. The alkylating agent is usually an alkyl halide or an equivalent compound with a good leaving group on carbon. Allyl halides are particularly attractive for SN2-type reactions due to the increased reactivity added by the allyl system. Celestolide (4-acetyl-6-t-butyl-1,1-dimethylindane, a component of musk perfume) can be synthesized using a benzyl anion alkylation with 3-chloro-2-methylprop-1-ene as an intermediate step.[8] The synthesis is fairly straightforward, and has been adapted for teaching purposes in an undergraduate laboratory.

References

[edit]- ^ E. J. Corey (1967). "General methods for the construction of complex molecules" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 14: 30–37. doi:10.1351/pac196714010019. S2CID 73595158.

- ^ E. J. Corey (1988). "Robert Robinson Lecture. Retrosynthetic thinking—essentials and examples". Chem. Soc. Rev. 17: 111–133. doi:10.1039/CS9881700111.

- ^ W. A. Smit, A. F. Buchkov, R. Cople (1998). Organic Synthesis, the science behind the art. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0-85404-544-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elias James Corey; Xue-Min Cheng (1995). The logic of chemical synthesis. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-471-11594-0.

- ^ Sarah J. Kodumal; Kedar G. Patel; Ralph Reid; Hugo G. Menzella; Mark Welch & Daniel V. Santi (November 2, 2004). "Total synthesis of long DNA sequences: Synthesis of a contiguous 32-kb polyketide synthase gene cluster". PNAS. 101 (44): 15573–15578. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10115573K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406911101. PMC 524854. PMID 15496466.

- ^ Linderman, Russell J.; Godfrey, Alex. (August 1988). "Novel synthesis of tetrahydrofurans via a synthetic equivalent to a carbonyl ylide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (18): 6249–6251. doi:10.1021/ja00226a052. PMID 22148812.

- ^ Whaley, W. M.; Govindachari, T. R. (1951). "The Pictet-Spengler Synthesis of Tetrahydroisoquinolines and Related Compounds". In Adams, R. (ed.). Organic Reactions. Vol. VI. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 151. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or006.03. ISBN 0471264180.

- ^ Kagabu, Shinzo; Kojima, Yuka (May 1992). "A synthesis of indane musk Celestolide". Journal of Chemical Education. 69 (5): 420. Bibcode:1992JChEd..69..420K. doi:10.1021/ed069p420.