Charles W. White

Charles White | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles Wilbert White, Jr. April 2, 1918 |

| Died | October 3, 1979 (aged 61) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Education | School of the Art Institute of Chicago |

| Known for | Painting; visual art |

| Notable work | The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy |

| Movement | New Negro Movement (Chicago Black Renaissance) |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Catlett (m. 1941-1946; divorced) Frances Barrett (m. 1950-1979; his death)[1] |

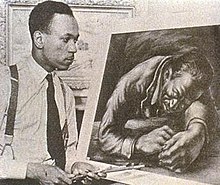

Charles Wilbert White, Jr. (April 2, 1918 – October 3, 1979) was an American artist known for his chronicling of African American related subjects in paintings, drawings, lithographs, and murals. White's lifelong commitment to chronicling the triumphs and struggles of his community in representational form cemented him as one of the most well-known artists in African American art history.

Following his death in 1979, White's work has been included in the permanent collections of the Art Institute of Chicago,[2] Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art,[3] The Newark Museum, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.[4] White's best known work is The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy, a mural at Hampton University. In 2018, the centenary year of his birth, the first major retrospective exhibition of his work was organized by the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]Charles Wilbert White was born on April 2, 1918, to Ethelene Gary, a domestic worker, and Charles White Sr., a railroad and construction worker, on the South Side of Chicago. Ethelene was born in Mississippi and came north in the Great Migration. She raised Charles, and as she had no child care, she would often leave him at the public library.[6] There, White developed an affinity for art and reading.[7] White's mother bought him a set of oil paints when he was seven years old, which hooked White on painting. White also played music as a child, studied modern dance, and was part of theatre groups; however, he stated that art was his true passion.[citation needed]

White's mother also took him to the Art Institute of Chicago, where he would read and look at paintings—developing a particular interest in the works of Winslow Homer and George Inness. Since White had little money growing up, he often painted on whatever surfaces he could find including shirts, cardboard, and window blinds. During the Great Depression, White tried to conceal his passion for art in fear of embarrassment; however, this ended when White got a job painting signs at the age of fourteen. White learned how to mix paints by sitting-in every day for a week on an Art Institute sponsored painting class that was taking place at a park near his home.[8] His mother remarried when White's father died in 1926. She married a steel mill worker who would become an abusive alcoholic, especially towards White. This experience lead him to escape into art. White had few opportunities to pursue his natural talent at this time due to the abuse and lack of resources from his household which was economically insufficient.[9] This is also the same year his mother began sending him to Mississippi twice a year to his aunts, Hasty and Harriet Baines, where he would learn about his heritage and African American Southern folklore. White showed persistence while battling abuse and poverty. He used his own experiences, curiosity and feelings about the neglected history of African Americans to help shape a common theme within his work.[7] An early activist, as a teenager, he volunteered his talents and became the house artist at the National Negro Congress in Chicago.[6] Later, in a union with fellow black artists, White was arrested while picketing.[7]

White won a grant during the seventh grade to attend Saturday art classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. After reading Alain Locke's book The New Negro: An Interpretation, a critique of the Harlem Renaissance,[10] White's social views changed. He learned after reading Locke's text about important African American figures in American history, and questioned his teachers on why they were not taught to students in school, causing some to label him a "rebel problematic child."[7] White did not graduate from high school, having lost a year due to his refusal to attend class after being disillusioned with the teaching system. While he was encouraged by his art teachers to submit his art works and won various scholarships, these would later be declared an "error" and be taken away from him and given to whites instead.[7] He was admitted to two art schools, each then pulled his acceptance because of his race.[11]

White ultimately received a full scholarship to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied from 1937 to 1938.[12] While there, White identified Mitchell Siporin, Francis Chapin, and Aaron Bohrod as his influences. He was an excellent draftsman, completing five drawing courses and received a final "A grade."[13] To pay the costs of art supplies, White became a cook, using his mother's instruction and recipes. White later became an art teacher at St. Elizabeth Catholic High School.[8]

Career

[edit]In 1940, White stated in an interview, "I am interested in the social, even the propagandistic angle of painting that will say what I have to say. Paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent."[14] In 1938, White was hired by the Illinois Art Project, a state affiliate of the Works Progress Administration. His work received an extended showing at the Chicago Coliseum during the Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro, which was part of the American Negro Exposition commemorating the 75th anniversary of Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery.[15] An important figure in what became known as the Chicago Black Renaissance, White taught art classes at the Southside Community Art Center.[6] Following his first show at Paragon Studios in Cincinnati in 1938, White's work was exhibited widely throughout the United States, including, among many others, exhibitions at the Roko Gallery, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1939 he produced his WPA mural Five Great American Negroes, now at Howard University Gallery of Art.[11] White also showed at the Palace of Culture in Warsaw and the Pushkin Museum. In 1976 his work was featured in Two Centuries of Black American Art, LACMA's first exhibition devoted exclusively to African-American Artists.[16]

White moved to New Orleans in 1941 to teach at Dillard University. That same year, he married sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett, who also taught at Dillard.[15] He served in the US Army during WWII, but was discharged when he contracted tuberculosis. In 1942, White and Catlett moved to New York City. While in New York City, White learned lithography and etching techniques at the Arts Student League, taking direction from renowned artist Harry Sternberg, who encouraged him to move beyond “stylization to individuation in his figures.” It was here that White honed his technical skills and developed a more deepened vision of black society.[9]

While in New York, White and Catlett met Viktor Lowenfeld, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany who taught at Hampton Institute in Virginia. Lowenfeld invited the couple to teach at Hampton.[17] While at the Hampton Institute, White painted one of his most well known works, The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy.[18] Measuring around 12 feet by seven feet,[19] the mural depicts a number of notable African-Americans including Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Peter Salem, George Washington Carver, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Marian Anderson.

In 1946, White and Catlett received a Rosenwald Fund Fellowship, which enabled them to move to Mexico City. There, White and Catlett joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular, an influential print shop collective focused on using art to advance revolutionary social causes. The couple divorced shortly after moving to Mexico.[20]

Printmaking enabled White to reach a wider public more directly and allowed him to bring together his social commitment and artistic practice. Although he had long been aware of art’s social utility, with his lithographs and linocuts he was finally able to communicate with a large, cross-national community of black workers and socialist artists, as opposed to his paintings, which were generally tied to individual purchasers. He started providing political cartoons for the Daily Worker and, in 1953, he published, in association with Masses and Mainstream, a portfolio of six reproductions of his ink-and-charcoal drawings, entitled Charles White: Six Drawings. Priced at $3—about $35.23 in 2024—this portfolio aimed at getting art to the people, a main concern for progressive artists of the period. In this respect it was a great success, and White himself acknowledged this when he learned that a group of workers in Alabama combined their savings to buy a portfolio and shared the pictures among themselves.[21]

In 1956, due to ongoing respiratory issues—potentially related from an earlier case of tuberculosis—White moved to Los Angeles for its drier, more mild climate.[6] From 1965 to his death in 1979, White taught at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles.[22] On faculty at Otis, he was a beacon for African American artists who came to study with him.[23] Among those he taught were Alonzo Davis, David Hammons, and Kerry James Marshall.[24] An elementary school was named after him and is located on the former Otis College campus.[25][26]

White was elected to the National Academy of Design in 1972. Later in life, White moved to Altadena, California, where he remained until his death of congestive heart failure in 1979.

Legacy

[edit]During his time at the Otis Art Institute, White was a mentor for many young Black artists, including Kerry James Marshall, Richard Wyatt Jr., David Hammons, and Alonzo Davis.[6][9][24] Marshall reflected that “Under [his] influence I always knew that I wanted to make work that was about something: history, culture, politics, social issues. (...) It was just a matter of mastering the skills to actually do it.”[27] He also inspired a generation of socially conscious African American artists like Benny Andrews, Faith Ringgold, and Dana Chandler and regularly attended exhibitions in Black art spaces like the Brockman Gallery, Gallery 32 and the Heritage Gallery.[6][9]

White's popularity faded after his death. According to M.H. Miller, “Part of this had to do with the fact that throughout the ’80s and ’90s, artists of color were rare in an industry that endorses the work of white men at the exclusion of everyone else.” Additionally, “during his lifetime and in the decades following, the figurative art that White championed was overshadowed by a more abstract or conceptual style.”[6]

Shortly after White's death, a park in Altadena, California, where he spent a great deal of his later years, was renamed Charles White Park—the first park to be named after an American-born artist.[28] The park hosted the Charles White Memorial Arts Festival from 1980 through to the early 1990s, and, in 2021, Altadena Arts hosted the first-ever Altadena Arts Festival, a reiteration of the Charles White Memorial Art Festival focused on celebrating artists of color, women artists, and artists with disabilities.[29][30]

White's works and writings are featured in the collections of Atlanta University,[31] the Barnett-Aden Gallery, Howard University,[32] the Library of Congress,[33][34] the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[35][36] the Minneapolis Institute of Art,[37] the Oakland Museum,[38] the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[39] the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,[40] Syracuse University and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.[41] The CEJJES Institute of Pomona, New York, owns a number of White's works and has established a dedicated Charles W. White Gallery.[42] In 2015, Drs. Susan G. and Edmund W. Gordon of Pomona, New York donated their collection of works by Charles White to the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas, Austin.[43]

Reception

[edit]In 1982, a retrospective exhibition of White's work was held at the Studio Museum in Harlem.[6] In the 1990s, the idea of staging a major traveling retrospective exhibition arose. Ultimately, over approximately a ten year period, staff from the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art attempted to locate various White pieces to put together an extensive exhibition of his work. The exhibition opened in Chicago in 2018, traveling to New York City and Los Angeles.[44][45]

White "was a humanist, drawn to the physical body and more literal representations of the lives of African-Americans," according to Lauren Warnecke for the Chicago Tribune.[44] While this put him out of step with the abstract movement in art, the power of his work is undeniable according to the Los Angeles Times' Christopher Knight, especially White's graphic work in graphite, charcoal, crayon and ink.[46] The Washington Post art critic, Philip Kennicott finds White's work central to American art.[47] "Grace, passion, coolness, toughness, [and] beauty" mark White's work, according to Holland Cotter in The New York Times; White had "the hand of an angel" and "the eye of a sage."[11]

In November 2019, two works by White went up for the first time in Christie's and Sotheby's main-seasonal New York City contemporary art auctions. Both works, Banner for Willie J. (1976)—a portrait of White's cousin, who was killed during an armed robbery—and Ye Shall Inherit the Earth (1953)—a charcoal drawing of civil rights icon Rosa Lee Ingram with a child in her arms—made sales records for the artist's work.[48][49][50]

References

[edit]- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths WHITE, FRANCES BARRETT". The New York Times. 15 October 2000. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Charles White". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ "Acquisition: Charles White". National Gallery of Art. April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "Artist Info". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Lopez, Ruth (June 5, 2018). "Key figure of the Chicago Black Renaissance, Charles White, finally gets his due". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 2018-06-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller, M.H. (September 28, 2018). "The Man Who Taught a Generation of Black Artists Gets His Own Retrospective". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Charles White 1913 - 1938". www.cejjesinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ^ a b "Oral history interview with Charles W. White, 1965 March 9", Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

- ^ a b c d Blum, Paul Von (1 December 2009). "Charles White: an artist for humanity's sake" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 3 (4): 27–37. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.599.690. Gale A306515936 ProQuest 237007314.

- ^ Sartorius, Tara Cady (February 1998). "Art across the Curriculum: Play by Play". Arts & Activities. 123 (1): 14–16. OCLC 425236169.

- ^ a b c Cotter, Holland (October 11, 2018). "Charles White Was a Giant, Even Among the Heroes He Painted". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- ^ "Celebrating Charles White | School of the Art Institute of Chicago". www.saic.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-09.

- ^ Wilson, Alona C. (2005). "Study of Charles White". International Review of African American Art. 20 (1): 46–47.

- ^ Elliot, Jeffrey; White, Charles (1978). "Charles White: Portrait of an Artist". Negro History Bulletin. 41 (3): 825–828. JSTOR 44213837.

- ^ a b Courage, Richard A. "Charles White and the Black Chicago Renaissance". iraaa.museum.hamptonu.edu. International Review of African American Art. Hampton University. Retrieved 2018-06-08.

- ^ "Checklist of Artworks" (PDF). LACMA. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Paul Von Blum, J. D. "Charles White: An Artist for Humanity’s Sake."

- ^ Hocker, Cliff. "VMFA Focus on African American Art". International Review of African American Art. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Breanne, Robertson (Spring 2016). "Pan-Americanism, Patriotism, and Race Pride in Charles White's Hampton Mural". American Art. 30 (1): 52–71. doi:10.1086/686548. S2CID 163452559.

- ^ "First Impressions: Elizabeth Catlett & Charles White at the Taller de Gráfica Popular". Swann Galleries News. 2023-10-03. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ John P. Murphy, ‘Charles White: The Politics of Print’, Print Quarterly, xxxvi, no. 2, June 2019, pp. 146–56.

- ^ Brock, Mary Sherwood, Otis Connections/ LA Printmaking in the 1960s "Otis Connections/ LA Printmaking in the 1960s" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ Thackara, Tess (11 October 2018). "Charles White's Artworks Made Him an Icon for Black Artists". Artsy. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Charles White". Digital Archive NOW DIG THIS!: ART AND BLACK LOS ANGELES 1960–1980. Hammer Museum. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Charles White". ucla.edu.

- ^ Office of Communications. "LACMA funding transformative renovation of Charles White Elementary School Art Gallery". LAUSDdaily.net. LAUSD. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Charles White". MoMA. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Charles White: The Artist and the Park". Unframed. 2013-09-12. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "First-ever Altadena Arts Festival Will Celebrate Local Visual Artists, Eclectic Array of Bands and Poetry". Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Home". Altadena Arts. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Box 1, Folder 22 | A Finding Aid to the Charles W. White papers, 1933-1987, bulk 1960s-1970s | Digitized Collection | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ Article, Jo Lawson-Tancred ShareShare This (2022-11-08). "A Rediscovered Charles White Drawing Stolen From Howard University in the 1970s Must Be Returned, a Judge Has Ruled". Artnet News. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Our war / artist, Charles White". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ ""Gideon" / Charles White '51". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Charles Wilbert White | Hope for the Future". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Charles Wilbert White | Melinda". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Just a Closer Walk with Thee, Charles White ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "2010.54.6040 | OMCA COLLECTIONS". collections.museumca.org. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Charles White | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Goodnight Irene". art.nelson-atkins.org. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "Guitarist (Primary Title) – (2001.10) – Collections". vmfa.museum. Retrieved 2024-06-10.

- ^ "The Charles White Gallery", The CEJJES Institute.

- ^ Ghorashi, Hannah (2015-05-05). "UT Austin Receives Significant Collection of Works By WPA Artist Charles White". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ a b Warnecke, Lauren (June 15, 2018). "It's a homecoming for artist Charles White at the Art Institute". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Norman, Lee Ann (June 18, 2018). "Poise And Dignity In Every View, A Review of Charles White at the Art Institute of Chicago". Newcity Art. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ^ Knight, Christopher (March 7, 2019). "Review: Charles White show at LACMA pinpoints the power of an underappreciated black artist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ Kennicott, Philip (October 18, 2018). "Charles White, who made some of this country's greatest art, transcends labels". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

White should be a household name, even among people who don't closely follow the art world....It shouldn't be possible to tell the history of American art without White figuring squarely in the middle of it.

- ^ Tully, Judd (2019-11-15). "Abstract Expressionism Leads Sotheby's Contemporary Sale in New York, with $30.1 M. Willem de Kooning Topping Market-Affirming $270.7 M. Total". ARTNews. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ Reyburn, Scott; Pogrebin, Robin (15 November 2019). "For Auctions, It's 'No Froth,' but 'Steady.' That's the New Normal". The New York Times.

- ^ Tully, Judd (2019-11-14). "At Solid $325.3 M. Christie's Contemporary Art Sale in New York, Ed Ruscha Is King". ARTNews. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

Further reading

[edit]- Finkelstein, Sidney (1953). "Charles White's Humanist Art". Masses & Mainstream. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Finkelstein, Sidney (1955). Charles White: Ein Künstler Amerikas. Verlag d. Kunst. p. 67. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- The Editors of ARTnews (2018-10-26). "From the Archives: Reviews of Charles White's Exhibitions Over the Decades". ARTnews. Retrieved 2018-11-29. (reviews from 1943 to 1976 that appeared in the paper)

- Oehler, Sarah Kelly; Adler, Esther, eds. (2018). Charles White: A Retrospective. Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 9780300232981. OCLC 1015275517.