Bamar people: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

rewrote article, added citations |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description| |

{{Short description|The majority ethnic group in Myanmar (Burma)}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2020}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|date=May 2015}} |

|||

{{Contains special characters|Burmese}} |

|||

{{Infobox ethnic group |

{{Infobox ethnic group |

||

| group = |

| group = Bamar |

||

| native_name = |

| native_name = {{my|ဗမာလူမျိုး}} |

||

| native_name_lang = my |

|||

| image = Burmese.JPG |

|||

| image = |

|||

| pop = '''{{circa}} 39 million'''<ref>[[Burmese Proper]] (35) + [[Burmese diaspora]] (4 million)</ref> |

|||

| image_caption = |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[File:Map of the Burmans Diaspora in the World.jpg|Map of the Burmans diaspora|center|frameless|280x280px]] --> |

|||

| image_alt = |

|||

| regions = {{flag|Myanmar}}{{nbsp|6}} 35,942,466<ref>{{cite web|url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=KP |title=Worldbank, 2020}}</ref><br/> |

|||

| image_upright = |

|||

'''Diaspora {{as of|2022|lc=on}}'''<br/>{{circa}} 3,890,902 million<ref name="MOFA">{{Cite book|publisher=Ministry of Foreign Affairs|location=South Korea|year=2019|access-date=2019-11-09|url=http://www.mofa.go.kr/www/wpge/m_21509/contents.do|title=재외동포현황(2019)/Total number of overseas Koreans (2019)}}</ref> |

|||

| |

| total = <!-- total population worldwide --> |

||

| |

| total_year = <!-- year of total population --> |

||

| |

| total_source = |

||

| total_ref = <!-- references supporting total population --> |

|||

| region2 = {{flag|Australia}} |

|||

| |

| genealogy = |

||

| |

| regions = {{flag|Myanmar}} {{circa}} 35 million |

||

| |

| languages = [[Burmese language|Burmese]] |

||

| religions = Predominantly [[Theravada Buddhism]] and [[Burmese folk religion]]<br/> |

|||

| pop3 = 110,000 |

|||

Minority [[Christianity]] and [[Islam]] |

|||

| ref3 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| related_groups = [[Danu people|Danu]], [[Intha people|Intha]], [[Rakhine people|Rakhine]], [[Marma people|Marma]], [[Achang people|Achang]] and other [[Sino-Tibetan peoples]] |

|||

| region4 = {{flag|Singapore}} |

|||

| |

| footnotes = |

||

| ref4 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region5 = {{flag|Malaysia}} |

|||

| pop5 = 66,500 |

|||

| ref5 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region6 = {{flag|South Korea}} |

|||

| pop6 = 22,000 |

|||

| ref6 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region7 = {{flag|Japan}} |

|||

| pop7 = 15,800 |

|||

| ref7 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region8 = {{flag|England}} |

|||

| pop8 = 9,800 |

|||

| ref8 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region9 = {{flag|UAE}} |

|||

| pop9 = 7,500 |

|||

| ref9 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region11 = {{flag|Germany}} |

|||

| pop11 = 7,300 |

|||

| ref11 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region12 = {{flag|Hong Kong}} |

|||

| pop12 = 5,400 |

|||

| ref12 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region13 = {{flag|Cambodia}} |

|||

| pop13 = 4,700 |

|||

| ref13 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region14 = {{flag|Norway}} |

|||

| pop14 = 1,500 |

|||

| ref14 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region15 = {{flag|New Zealand}} |

|||

| pop15 = 1,000 |

|||

| ref15 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region16 = {{flag|France}} |

|||

| pop16 = 900 |

|||

| ref16 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region17 = {{flag|Sweden}} |

|||

| pop17 = 800 |

|||

| ref17 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region18 = {{flag|Pakistan}} |

|||

| pop18 = 200 |

|||

| ref18 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region19 = {{flag|Taiwan}} |

|||

| pop19 = 40,000 |

|||

| ref19 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region20 = {{flag|Vatican}} |

|||

| pop20 = 20 |

|||

| ref20 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region21 = {{flag|India}} |

|||

| pop21 = 100 |

|||

| ref21 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region22 = {{flag|Canada}} |

|||

| pop22 = 9,300 |

|||

| ref22 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region23 = {{flag|Chad}} |

|||

| pop23 = 45 |

|||

| ref23 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region24 = {{flag|Denmark}} |

|||

| pop24 = 1,764 |

|||

| ref24 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region25 = {{flag|Saudi Arabia}} |

|||

| pop25 = 50,000 |

|||

| ref25 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region26 = {{flag|Luxembourg}} |

|||

| pop26 = 11 |

|||

| ref26 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region27 = {{flag|Nepal}} |

|||

| pop27 = 20 |

|||

| ref27 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region28 = {{flag|Kuwait}} |

|||

| pop28 = 10 |

|||

| ref28 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region29 = {{flag|Italy}} |

|||

| pop29 = 35 |

|||

| ref29 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region30 = {{flag|Netherlands}} |

|||

| pop30 = 30 |

|||

| ref30 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region31 = {{flag|Finland}} |

|||

| pop31 = 30 |

|||

| ref31 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region32 = {{flag|Sri Lanka}} |

|||

| pop32 = 15 |

|||

| ref32 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| region33 = {{flag|China}} |

|||

| pop33 = 20,000 |

|||

| ref33 = <ref name="MOFA"/> |

|||

| langs = '''[[Burmese language|Burmese]]'''<ref>{{Ethnologue17|kor}}</ref> |

|||

{{flatlist}} |

|||

{{endflatlist}} |

|||

| rels = [[Theravada Buddhism]] |

|||

| related_groups = [[Sino-Tibetan language]] speaking people |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{distinguish||text=[[Burmese]], the demonym for people from Myanmar (Burma)}} |

|||

The '''Bamar''' ({{MYname|MY=ဗမာလူမျိုး|MLCTS=ba. ma lu myui:}}, {{IPA-my|bəmà lùmjó|IPA}}; historically '''Mranmas'''; also known as the '''Burmans''', '''Burmese''', or '''Myanmars'''<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sargent |first=Inge |title=Twilight Over Burma: My life as a Shan Princess |publisher=[[University of Hawaii Press]] |year=1994 |isbn=0824816285 |location=Honolulu |pages=xv |language=English}}</ref>) are a Southeast Asian [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan]] [[ethnic group]] native to [[Myanmar]] (formerly Burma). The Bamar live primarily in the [[Irrawaddy River|Irrawaddy River basin]] and speak the [[Burmese language]], which is the sole official language of Myanmar at a national level.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/burma/|title=The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency|website=www.cia.gov|language=en|access-date=2018-07-09}}</ref> Bamar customs and identity are closely intertwined with the broader culture of Myanmar. |

|||

{{Contains special characters|Burmese}} |

|||

The '''Bamar''' ({{MYname|MY=ဗမာလူမျိုး|MLCTS=ba. ma lu myui:}}, {{IPA-my|bəmà lùmjó|IPA}}; also known as the '''Burmans''') are a [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan]] [[ethnic group]] native to [[Myanmar]] (formerly Burma) in [[Southeast Asia]]. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar, constituting 68% of the country's population.<ref name=":0">{{Citation |title=Country Summary |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/burma/summaries |work=The World Factbook |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |language=en |access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref> The geographic homeland of the Bamar is the [[Irrawaddy River|Irrawaddy River basin]]. [[Burmese language|Burmese]] is the native language of the Bamar, as well as the [[national language]] and [[lingua franca]] of Myanmar.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

==Origins== |

|||

The Bamar speak Burmese, a [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan language]]. The Burmese-speaking people first migrated from present-day [[Yunnan]], China to the Irrawaddy valley in the 7th century. Over the following centuries, the Burmese speakers absorbed other ethnic groups such as the [[Pyu people|Pyu]] and the [[Mon people|Mon]].<ref name=ms-8>{{cite journal |last1=Summerer |first1=Monika |last2=Horst |first2=Jürgen |last3=Erhart |first3=Gertraud |last4=Weißensteiner |first4=Hansi |last5=Schönherr |first5=Sebastian |last6=Pacher |first6=Dominic |last7=Forer |first7=Lukas |last8=Horst |first8=David |last9=Manhart |first9=Angelika |last10=Horst |first10=Basil |last11=Sanguansermsri |first11=Torpong |last12=Kloss-Brandstätter |first12=Anita |title=Large-scale mitochondrial DNA analysis in Southeast Asia reveals evolutionary effects of cultural isolation in the multi-ethnic population of Myanmar |journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology |date=2014 |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=17 |doi=10.1186/1471-2148-14-17 |pmc=3913319 |pmid=24467713 }}</ref><ref>{{harv|Myint-U|2006|pp=51–52}}</ref> A 2014 DNA analysis shows that Burmese people were "typical [[Southeast Asia]]n" but "also with [[Northeast Asia]]n and [[South Asia]]n influences" and that the gene pool of the Bamar was far more diverse than other ethnic groups such as the [[Karen people]]. They are closer to the [[Yi people|Yi]] and [[Mon people]] than to the [[Karen people|Karen]].<ref name=ms-8/> |

|||

== Ethnonyms == |

|||

Ninth century Chinese sources indicate that [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan]]-speaking tribes were present near today's [[Irrawaddy River]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Brief History of Achang People|publisher=民族出版社|year=2008|isbn=9787105087105}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Book of Man|publisher=中国书店出版社|year=2007|isbn=9787805684765}}</ref> These tribes were considered ancestors of Bamar people.<ref>{{Cite book|title=民族学报, Volume 2|publisher=Yunnan Nationalities University|year=1982|pages=37, 38, 48}}</ref> |

|||

{{Also|Names of Myanmar}} |

|||

In the [[Burmese language]], '''Bamar''' (ဗမာ, also transcribed '''Bama''') and '''Myanmar''' (မြန်မာ, also transliterated '''Mranma''' and transcribed '''Myanma''') have historically been interchangeable [[Endonym and exonym|endonyms]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bradley |first=David |date=2019-01-28 |title=Language policy and language planning in mainland Southeast Asia: Myanmar and Lisu |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/lingvan-2018-0071/html |journal=Linguistics Vanguard |language=en |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=20180071 |doi=10.1515/lingvan-2018-0071 |issn=2199-174X}}</ref> Burmese is a [[Diglossia|diglossic language]]; "Bamar" is the diglossic low form of "Myanmar," which is the diglossic high equivalent.<ref name=":10">{{Citation |last=Bradley |first=David |title=17 Typological profile of Burmic languages |date=2021-08-09 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110558142-017/html |work=The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia |pages=299–336 |editor-last=Sidwell |editor-first=Paul |publisher=De Gruyter |doi=10.1515/9783110558142-017 |isbn=978-3-11-055814-2 |access-date=2022-08-22 |editor2-last=Jenny |editor2-first=Mathias}}</ref> The term "Myanmar" is extant to the early 1100s, first appearing on a stone inscription, where it was used as a cultural identifier, and has continued to be used in this manner.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal |last=Aung-Thwin |first=Michael |author-link=Michael Aung-Thwin |date=June 2008 |title=Mranma Pran: When context encounters notion |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-southeast-asian-studies/article/abs/mranma-pran-when-context-encounters-notion/A0768468DD8E4755B18BA5EEA43BC992 |journal=Journal of Southeast Asian Studies |language=en |volume=39 |issue=2 |pages=193–217 |doi=10.1017/S0022463408000179 |issn=1474-0680}}</ref> From the onset of [[British rule in Burma|British colonial rule]] to the [[Japanese occupation of Burma|Japanese occupation]] of Burma, "Bamar" was used in Burmese to refer to both the country and its majority ethnic group.<ref name=":14">{{Cite journal |last=Bradley |first=David |date=2019-01-28 |title=Language policy and language planning in mainland Southeast Asia: Myanmar and Lisu |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/lingvan-2018-0071/html |journal=Linguistics Vanguard |language=en |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=20180071 |doi=10.1515/lingvan-2018-0071 |issn=2199-174X}}</ref> Since the country achieved [[Independence Day (Myanmar)|independence in 1948]], "Myanmar" has been officially used to designate both the nation-state and its official language, while "Bamar" has been used to designate the majority ethnic group, especially in written contexts.<ref name=":14" /> In spoken usage, "Bamar" and "Myanmar" remain interchangeable, especially with respect to referencing the language and country.<ref name=":14" /> |

|||

In the [[English language]], the Bamar are known by a number of exonyms, including '''Burmans''' and '''Burmese''', both of which were interchangeably used by the British.{{NoteTag|Historical spellings include 'Birman'.}} In June 1989, in an attempt to indigenise both the country's place names and ethnonyms, the [[State Peace and Development Council|military government]] changed the official English names of the country (from Burma to Myanmar), the language (from Burmese to Myanmar), and the country's majority ethnic group (from Burmans to Bamar).<ref>{{Cite web |date=1989-06-21 |title=Burma Decides It's the 'Union of Myanmar' |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-06-21-mn-2419-story.html |access-date=2022-08-21 |website=Los Angeles Times |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Notes |date=1998-07-01 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780804765121-024/html |work=Asian Security Practice |pages=701–744 |editor-last=Alagappa |editor-first=Muthiah |publisher=Stanford University Press |doi=10.1515/9780804765121-024 |isbn=978-0-8047-6512-1 |access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Guyot |first=James F. |last2=Badgley |first2=John |date=1990 |title=Myanmar in 1989: Tatmadaw V |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2644897 |journal=Asian Survey |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=187–195 |doi=10.2307/2644897 |issn=0004-4687}}</ref> |

|||

==Languages== |

|||

[[File:WIKITONGUES- Naw speaking Burmese.webm|thumb|A Burmese speaker, recorded in [[Taiwan]].]] |

|||

[[Burmese language|Burmese]] is spoken by the Bamar but is also widely spoken by ethnic minorities and other nationalities in Myanmar. Its core vocabulary consists of [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan]] words, but many terms associated with [[Buddhism]], arts, sciences and government have derived from the [[Indo-European languages]] of [[Pali]] and [[English language|English]]. |

|||

== Ancestral origins == |

|||

The [[Rakhine people|Rakhine]], although culturally distinct from the Bamar, are ethnically related and speak a dialect of Burmese that includes retention of the {{IPA|/r/}} sound, which has coalesced into the {{IPA|/j/}} sound in standard Burmese (although it is still present in orthography). |

|||

{{Main|Early Pagan Kingdom}}{{multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| total_width = 320 |

|||

| image1 = Pagan-kingdom.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = The extent of the 11th century [[Pagan Empire]] under [[Anawrahta]] |

|||

| image2 = Ethnolinguistic map of Burma 1972 en.svg |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

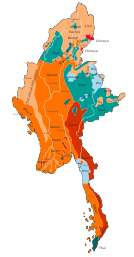

| caption2 = The Bamar continue to inhabit the fertile low-lying river valleys in the centre of Myanmar (in orange). |

|||

| footer = |

|||

}} |

|||

The Bamar's northern origins are evidenced by the extant distribution of [[Burmish languages]] to the north of the country, and the fact that ''taung'' (တောင်), the Burmese word for 'south' also means 'mountain,' which suggests that at one point ancestors of the Bamar lived north of the [[Himalayas]].<ref name=":2">{{Citation |title=Burmese |date=2019 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/historical-phonology-of-tibetan-burmese-and-chinese/burmese/CAECA9BA3FF80C3E4770795D13589F17 |work=The Historical Phonology of Tibetan, Burmese, and Chinese |pages=46–83 |editor-last=Hill |editor-first=Nathan W. |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/9781316550939.003 |isbn=978-1-107-14648-8 |access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref> Until a thousand years ago, ancestors of the Bamar and [[Yi people|Yi]] were much more widespread across Yunnan, Guizhou, southern Sichuan, and northern Burma.{{NoteTag|The Tanguts of Western Xia (to the north of Yunnan around this time) spoke a Tibeto-Burman language that may also have been close to Burmese-Yi. Going further back in time, the people of the ancient kingdom of Sanxingdui in Sichuan (in the 12th–11th centuries BCE) were probably ancestral to later Tibeto-Burman groups and perhaps even more narrowly, to the ancestors of the Burmese-Yi speakers at Dian and Yelang.}} During the [[Han dynasty]] in China, Yunnan was ruled primarily by the Burmese-Yi speaking [[Dian Kingdom|Dian]] and [[Yelang]] kingdoms. During the [[Tang dynasty]] in China, Yunnan and northern Burma were ruled by the Burmese-Yi speaking [[Kingdom of Nanzhao|Nanzhao]] kingdom. [[File:Bodleian Ms. Burm. a. 5 fol 181.jpg|thumb|[[Paddy field|Wet rice cultivation]] is closely associated with the Bamar.]]Between the 600s to 800s, the Bamar had cut through the Himalayas, and down the [[Irrawaddy River|Irrawaddy]] (Ayeyarwady) and [[Salween River|Salween]] (Thanlwin) Rivers in large numbers, establishing the outpost of [[Bagan|Pagan]] (Bagan).<ref>{{Citation |last=Goh |first=Geok Yian |title=Commercial Networks and Economic Structures of Theravada Buddhist Southeast Asia (Thailand and Myanmar) |date=2021-02-23 |url=https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-546 |work=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.546 |isbn=978-0-19-027772-7 |access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3648200277/GVRL?u=wikipedia&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=c3e2019a |title=Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life |publisher=Gale |year=2017 |edition=3rd |volume=3 |location=Farmington Hills |pages=206-212 |language=en |chapter=Burmans/Myanmarans}}</ref> The Bamar gradually settled in the fertile Irrawaddy and Salween river valleys that were home to [[Pyu city-states]], where they established the [[Pagan Kingdom]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Minahan |first=James |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=abNDLZQ6quYC&newbks=0&printsec=frontcover&q=bamar&hl=en |title=Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia |date=2012 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-59884-659-1 |language=en}}</ref> Between the 1050s to 1060s, King [[Anawrahta]] founded the [[Pagan Kingdom|Pagan Empire]], for the first time unifying the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery under one polity. By the 1100s, the [[Burmese language]] and culture had became dominant in the upper Irrawaddy valley, eclipsing Pyu (formerly called Tircul) and [[Pali]] norms. Conventional [[Burmese chronicles]] state that the [[Pyu]] were assimilated into the Bamar population. By the 1200s, Bamar settlements were found as far south as Mergui (Myeik) and Tenassarim (Taninthayi), both of which remain home to archaic Burmese dialects.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hudson |first=Bob |url=https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199355358.013.11 |title=The Oxford Handbook of Early Southeast Asia |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2022 |isbn=9780199355372 |editor-last=Higham |editor-first=Charles F. W. |language=en |chapter=Early States in Myanmar |editor-last2=Kim |editor-first2=Nam C.}}</ref> By the 1400s, Burmese speakers had also migrated westward, settling in what is now Rakhine State, where they eventually became the Rakhine (also called [[Rakhine people|Arakanese]]).<ref>{{Citation |last=Charney |first=Michael W. |title=Religion and Migration in Rakhine |date=2021-08-31 |url=https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-414 |work=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.414 |isbn=978-0-19-027772-7 |access-date=2022-09-11}}</ref> |

|||

=== Genetics === |

|||

Additional dialects come from coastal areas of [[Tanintharyi Region]] including Myeik (Beik) and [[Dawei]] (Tavoyan) as well as inland and isolated areas like Yaw. |

|||

A 2014 DNA analysis found that the Bamar exhibited 'extraordinary' genetic diversity, with 80 different mitochondrial lineages and indications of recent demographic expansion.<ref name="ms-8">{{cite journal |last1=Summerer |first1=Monika |last2=Horst |first2=Jürgen |last3=Erhart |first3=Gertraud |last4=Weißensteiner |first4=Hansi |last5=Schönherr |first5=Sebastian |last6=Pacher |first6=Dominic |last7=Forer |first7=Lukas |last8=Horst |first8=David |last9=Manhart |first9=Angelika |last10=Horst |first10=Basil |last11=Sanguansermsri |first11=Torpong |last12=Kloss-Brandstätter |first12=Anita |date=2014 |title=Large-scale mitochondrial DNA analysis in Southeast Asia reveals evolutionary effects of cultural isolation in the multi-ethnic population of Myanmar |journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=17 |doi=10.1186/1471-2148-14-17 |pmc=3913319 |pmid=24467713}}</ref> As the Bamar expanded their presence in the region following their arrival by the 800s, they likely incorporated older [[Haplogroup|haplogroups]] like those of the Pyu and Mon.<ref name="ms-8" /> Another genetic study of [[Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase|G6PD]] mutations in Mon and Bamar men found that they likely share a common ancestry, despite speaking languages that belong to different language families.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Nuchprayoon |first=Issarang |last2=Louicharoen |first2=Chalisa |last3=Charoenvej |first3=Warisa |date=2008-01 |title=Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase mutations in Mon and Burmese of southern Myanmar |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/jhg2008206 |journal=Journal of Human Genetics |language=en |volume=53 |issue=1 |pages=48–54 |doi=10.1007/s10038-007-0217-3 |issn=1435-232X}}</ref> |

|||

== Ethnic identity == |

|||

Other dialects are Taungyoe, Danu and [[Intha people|Intha]] in [[Shan State]].{{sfn|Gordon|2005}} |

|||

Modern-day Bamar identity remains permeable and dynamic, and is generally distinguished by language and religion, i.e., the Burmese language and Theravada Buddhism.<ref name=":6">{{Citation |title=4. Burman Territories and Borders in the Making of a Myanmar Nation State |date=2016-12-31 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1355/9789814695770-010/html |work=Myanmar's Mountain and Maritime Borderscapes |pages=99–120 |editor-last=Oh |editor-first=Su-Ann |publisher=ISEAS Publishing |doi=10.1355/9789814695770-010 |isbn=978-981-4695-77-0 |access-date=2022-08-22}}</ref> There is considerable variation among individuals who identify as Bamar, and members of other ethnic groups, particularly the [[Mon people|Mon]], [[Shan people|Shan]], [[Karen people|Karen]], and [[Chinese people in Myanmar|Sino-Burmese]], self-identify as Bamar to various degrees, some to the extent of complete assimilation.<ref name=":17" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=2014-04-11 |title=Old identity, new identification for Mandalay minorities |url=https://www.mmtimes.com/national-news/10155-old-identity-new-identification-for-mandalay-minorities.html |access-date=2022-08-26 |website=The Myanmar Times}}</ref> To this day, the Burmese language does not have precise terminology that distinguishes the Western concepts of race, ethnicity and religion; the term ''lu-myo'' ({{my|လူမျိုး}}, {{lit|type of person}}) can reference all three.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2020-08-28 |title=Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar |url=https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/312-identity-crisis-ethnicity-and-conflict-myanmar |website=International Crisis Group}}</ref> For instance, many Bamar self-identify as members of the 'Buddhist ''lu-myo''' or the '[[Burmese people|Myanmar ''lu-myo'']],' which has posed a significant challenge for census-takers.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Callahan |first=Mary P. |date=2017 |title=Distorted, Dangerous Data? Lumyo in the 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/665626 |journal=Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia |volume=32 |issue=2 |pages=452–478 |issn=1793-2858}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Saya_Chone's_"Royal_Audience".png|thumb|[[Saya Chone]]'s "Royal Audience," a traditional painting depicting the Mandalay Palace's royal audience hall]] |

|||

In the pre-colonial era, ethnic identity was fluid and dynamic, marked by patron-client relationships, religion, and regional origins.<ref>{{Citation |last=Thawnghmung |first=Ardeth Maung |title=“National Races” in Myanmar |date=2022-04-20 |url=https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-656 |work=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.656 |isbn=978-0-19-027772-7 |access-date=2022-08-21}}</ref> Consequently, many non-Bamar assimilated and adopted a Bamar identity and norms for sociopolitical purposes.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Walton |first=Matthew J. |date=2013-02-01 |title=The “Wages of Burman-ness:” Ethnicity and Burman Privilege in Contemporary Myanmar |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2012.730892 |journal=Journal of Contemporary Asia |volume=43 |issue=1 |pages=1–27 |doi=10.1080/00472336.2012.730892 |issn=0047-2336}}</ref> Between the 1500s and 1800s, the notion of Bamar identity expanded significantly, driven by intermarriage with other communities and voluntary changes in self-identification, especially in Mon and Shan-speaking regions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=South |first=Ashley |last2=Lall |first2=Marie |date=2016 |title=Language, Education and the Peace Process in Myanmar |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/content/crossref/journals/contemporary_southeast_asia_a_journal_of_international_and_strategic_affairs/v038/38.1.south.html |journal=Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs |language=en |volume=38 |issue=1 |pages=128–153 |doi=10.1353/csa.2016.0009 |issn=1793-284X}}</ref><ref name=":5">{{Citation |title=9. Was the Seventeenth Century a Watershed in Burmese History? |date=2018-12-31 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7591/9781501732171-014/html |work=Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era |pages=214–249 |editor-last=Reid |editor-first=Anthony J. S. |publisher=Cornell University Press |doi=10.7591/9781501732171-014 |isbn=978-1-5017-3217-1 |access-date=2022-08-22}}</ref> Bamar identity was also more inclusive in the precolonial era, especially during 1700s when [[Konbaung dynasty|Konbaung kings]] embarked on major territorial expansion campaigns, to [[Manipur Kingdom|Manipur]], [[Ahom kingdom|Assam]], [[Mrauk U]], and [[Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom|Pegu]].<ref name=":4" /> These campaigns paralleled those in other Southeast Asian kingdoms, such as Vietnam's southward expansion ([[Nam tiến]]), which wrested control of the [[Mekong Delta|Mekong delta]] from the [[Champa]] during the same period. |

|||

[[File:Burmese_family_portrait.JPG|right|thumb|Portrait of a Bamar family at the turn of the 20th century, during British rule]] |

|||

In the early 1900s, a narrower strain of Bamar nationalism developed in response to British colonial rule, which failed to address Bamar grievances and actively marginalised the Bamar from [[Public sphere|public spheres]] such as education and the armed forces.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Taylor |first=Robert H. |date=2005-11-01 |title=Do States Make Nations? |url=https://doi.org/10.5367/000000005775179676 |journal=South East Asia Research |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=261–286 |doi=10.5367/000000005775179676 |issn=0967-828X}}</ref><ref name=":4" /> The British employed [[divide and rule]] tactics which fostered mistrust between the Bamar and ethnic minorities, and would have consequential effects on Burmese ethnic identity and politics in the post-colonial era.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Han |first=Enze |date=2019-10-10 |title=Comparative Nation Building across the Borderland Area |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/34954/chapter/298578700 |language=en |doi=10.1093/oso/9780190688301.003.0007}}</ref> In 1925, the British discharged all Bamar soldiers from the colonial army, and adopted an exclusionary policy of recruiting only among the Chin, Kachin and Karen minorities, and by 1930 the [[Thakins|Dobama Asiayone]], a leading Burmese nationalist group had emerged, from which independence leaders like [[U Nu]] and [[Aung San]] would launch their political careers.<ref name=":17">{{Cite book |last=Houtman |first=Gustaaf |url=https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3403700448/GVRL?u=wikipedia&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=15d6cdb3 |title=Encyclopedia of Modern Asia |publisher=Charles Scribner's Sons |year=2002 |editor-last=Christensen |editor-first=Karen |location=New York |pages=383-384 |language=en |chapter=Burmans |editor-last2=Levinson |editor-first2=David}}</ref><ref name=":4" /> For most of its colonial history, Burma was administered as a province of [[Presidencies and provinces of British India|British India]]. It was not until 1937 that Burma was formally separated and became directly administered by the [[The Crown|British Crown]], after a long struggle for direct colonial representation.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Schober |first=Juliane |date=2010-11-30 |title=The Emergence of the Secular in Modern Burma |url=https://academic.oup.com/hawaii-scholarship-online/book/16781/chapter/173930816 |language=en |doi=10.21313/hawaii/9780824833824.003.0003}}</ref> |

|||

=== Government classification === |

|||

English was introduced in the 1800s when the Bamar first came into contact with the British as a trading nation and continued to flourish under subsequent [[British rule in Burma|colonial rule]]. |

|||

The Burmese government officially classifies nine 'ethnic groups' under the Bamar 'national race.'<ref name=":18">{{Cite web |last=Than Tun Win |title=Composition of the Different Ethnic Groups under the 8 Major National Ethnic Races in Myanmar |url=https://www.embassyofmyanmar.be/ABOUT/ethnicgroups.htm |website=Embassy of the Union of Myanmar, Brussels}}</ref> Of these nine groups, the Bamar, Dawei (Tavoyan), Myeik or Beik (Merguese), Yaw, and Yabein, all speak dialects of the Burmese language.<ref name=":18" /> One group, the [[Hpon language|Hpon]], speak a [[Burmish languages|Burmish language]] closely related to Burmese.<ref name=":18" /> Two groups, the [[Kadu language|Kadu]] and [[Ganan language|Ganan]], speak more distantly related Sino-Tibetan languages. The last group, the [[Moken]] (Salon in Burmese), speak an unrelated [[Austronesian languages|Austronesian language]].<ref name=":18" /> The Burmese-speaking [[Danu people|Danu]] and [[Intha people|Intha]] are classified under the [[Shan people|Shan]] 'national race.'<ref name=":18" /> |

|||

== Geographic distribution == |

|||

==Distribution== |

|||

=== Myanmar === |

|||

The Bamar are most numerous in Myanmar, constituting the majority ethnic group at around two thirds of the total population of about 54 million people in 2019.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.un.org/sg/sites/www.un.org.sg/files/atoms/files/Myanmar%20Report%20-%20May%202019.pdf|title=A BRIEF AND INDEPENDENT INQUIRY INTO THE INVOLVEMENT OF THE UNITED NATIONS IN MYANMAR FROM 2010 TO 2018|first=Gert |last=Rosenthal|date=29 May 2019|website=un.org}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Myanmar_states_location.svg|right|thumb|Myanmar's [[Administrative divisions of Myanmar|seven regions]] (in pale yellow) are home to the majority of the Bamar.]] |

|||

The Bamar predominantly live at the confluence of the [[Irrawaddy River|Irrawaddy]], Salween, and [[Sittaung River]] valleys in the centre of the country, which roughly encompass the country's [[Administrative divisions of Myanmar|seven administrative regions]], namely [[Sagaing Region|Sagaing]], [[Magway Region|Magwe]], [[Mandalay Region|Mandalay]] in [[Upper Myanmar]], as well as [[Bago Region|Bago]], [[Yangon Region|Yangon]], [[Ayeyarwady Region|Ayeyarwady]] and [[Tanintharyi Region|Taninthayi Regions]] in [[Lower Myanmar]]. However, the Bamar, particularly labour migrants, are found throughout all 14 of Myanmar's regions and states.<ref>{{Citation |last=Boutry |first=Maxime |title=Internal Migration in Myanmar |date=2020 |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7_9 |work=Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia |pages=163–183 |editor-last=Bell |editor-first=Martin |place=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7_9 |isbn=978-3-030-44009-1 |access-date=2022-09-11 |editor2-last=Bernard |editor2-first=Aude |editor3-last=Charles-Edwards |editor3-first=Elin |editor4-last=Zhu |editor4-first=Yu}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Ethnic Bamar men, Bagan, Myanmar.jpg|thumb|Men on an ox-drawn cart in [[Bagan]], a historic royal capital in the Anya region, the cultural heartland of the Bamar.]] |

|||

The cultural heartland of the Bamar is called Anya (အညာ, {{Lit|upstream}}, also spelt Anyar), which is the area adjoining the upper reaches of the Irrawaddy River, and centred around Sagaing, Magwe, and Mandalay.<ref name=":3" /><ref>{{Cite book |url=http://sealang.net/burmese/ |title=Myanmar-English Dictionary |publisher=Myanmar Language Commission |year=1993 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=":7">{{Citation |title=CHAPTER II. BURMA: THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE |date=1942-12-31 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1525/9780520351851-005/html |work=Modern Burma |pages=9–22 |publisher=University of California Press |doi=10.1525/9780520351851-005 |isbn=978-0-520-35185-1 |access-date=2022-08-22}}</ref> This region is often called the 'central dry zone' in English due to its paucity of rainfall and reliance on water irrigation.<ref name=":7" /> For 1,100 years, this region was home to a series of [[List of capitals of Myanmar|Burmese royal capitals]], until the British annexed Upper Burma (the last remaining part of the [[Konbaung dynasty|Konbaung Kingdom]]) in 1885.<ref name=":3" /> Bamar from this region are called ''anyar thar'' (အညာသား) in Burmese.<ref>{{Citation |title=13 Without the Mon Paradigm |date=2020-12-31 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780824874414-014/html |work=The Mists of Rāmañña |pages=299–322 |publisher=University of Hawaii Press |doi=10.1515/9780824874414-014 |isbn=978-0-8248-7441-4 |access-date=2022-08-22}}</ref> |

|||

In the 1500s, with the expansion of the [[First Toungoo Empire|Toungoo Empire]], the Bamar began populating the lower stretches of the Irrawaddy River valley, including [[Taungoo]] and [[Pyay|Prome]] (now Pyay), helping to disseminate the Burmese language and Bamar social customs.<ref name=":5" /> This influx of migration to historically Mon-speaking regions coincided with the rise of King [[Tabinshwehti]].<ref name=":19">{{Cite journal |last=Wallis |first=Keziah |date=2021 |title=Nats in the Land of the Hintha: Village Religion in Lower Myanmar |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/798153 |journal=Journal of Burma Studies |language=en |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=193–226 |doi=10.1353/jbs.2021.0010 |issn=2010-314X}}</ref> This pattern of migration intensified during the Konbaung dynasty, particularly among men specialised in wet rice cultivation, as women and children were generally prohibited from emigrating.<ref name=":19" /> Following the British annexation of [[Lower Burma]] in 1852, millions of Bamar from the Anya region resettled in the sparsely populated [[Irrawaddy Delta|Irrawaddy delta]] between 1858 and 1941.<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal |last=Kyaw |first=Nyi Nyi |date=2019-05-04 |title=Adulteration of pure native blood by aliens? mixed race kapya in colonial and post-Colonial Myanmar |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2018.1499223 |journal=Social Identities |volume=25 |issue=3 |pages=345–359 |doi=10.1080/13504630.2018.1499223 |issn=1350-4630}}</ref><ref name=":6" /> The Bamar were drawn to this 'rice frontier' by the British colonial authorities, who were eager to scale rice cultivation in the colony, and attract skilled Bamar farmers.<ref name=":6" /> By the 1890s, the British had established another centre of power and political economy in the Irrawaddy delta.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

The [[Burmese diaspora]], which is a recent phenomenon in historical terms and began at the start of World War II, has been mainly brought about by a protracted period of military rule and reflects the ethnic diversity of Myanmar. Many have settled in Europe, particularly in Great Britain. |

|||

=== Diaspora === |

|||

Following [[Myanmar#Independence (1948–1962)|Myanmar's Independence (1948–1962)]], many began moving to the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, United States, Malaysia, Singapore, mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, India and Japan.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kiik|first=Laur|date=2020|title=Confluences amid Conflict: How Resisting China's Myitsone Dam Project Linked Kachin and Bamar Nationalisms in War-Torn Burma|url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/778559|journal=Journal of Burma Studies|language=en|volume=24|issue=2|pages=229–273|doi=10.1353/jbs.2020.0010|s2cid=231624929|issn=2010-314X}}</ref> |

|||

The Bamar have emigrated to neighbouring Asian countries as well as Western countries, mirroring the migration patterns of the broader [[Burmese diaspora]]. Significant migration began at the start of World War II, and has continued through decades of military rule, economic decline and political instability. Many have settled in Europe, particularly in Great Britain. Following [[Myanmar#Independence (1948%E2%80%931962)|Myanmar's Independence (1948–1962)]], many began moving to the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, United States, Malaysia, Singapore, mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, India and Japan.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kiik |first=Laur |date=2020 |title=Confluences amid Conflict: How Resisting China's Myitsone Dam Project Linked Kachin and Bamar Nationalisms in War-Torn Burma |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/778559 |journal=Journal of Burma Studies |language=en |volume=24 |issue=2 |pages=229–273 |doi=10.1353/jbs.2020.0010 |issn=2010-314X |s2cid=231624929}}</ref> |

|||

== Language == |

|||

{{Main|Burmese language}} |

|||

[[File:Myazedi-Inscription-Burmese.JPG|thumb|The [[Myazedi inscription]], dated to 1113, is the oldest surviving stone inscription of the Burmese language.]] |

|||

[[Burmese language|Burmese]], a member of the [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan language family]], is the native language of the Bamar,<ref name=":2" /> and the national language of Myanmar. Burmese is the most widely spoken [[Tibeto-Burman]] language, and used as a [[lingua franca]] in Myanmar by 97% of the country's population.<ref>{{Citation |last=Bradley |first=David |title=Burmese as a lingua franca |date=1996-12-31 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110819724.2.745/html |work=Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas |pages=745–748 |editor-last=Wurm |editor-first=Stephen A. |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |doi=10.1515/9783110819724.2.745 |isbn=978-3-11-013417-9 |access-date=2022-08-22 |editor2-last=Mühlhäusler |editor2-first=Peter |editor3-last=Tryon |editor3-first=Darrell T.}}</ref> Burmese is a [[Diglossia|diglossic language]] with literary high and spoken low forms. The literary form of Burmese preserves many conservative classical forms and grammatical particles traced back to [[Old Burmese]] stone inscriptions, but are no longer used in spoken Burmese.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bradley |first=David |date=Spring 1993 |title=Pronouns in Burmese-Lolo |url=http://sealang.net/sala/archives/pdf4/bradley1993pronouns.pdf |journal=Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area |volume=16 |issue=1}}</ref> |

|||

[[Pali]], the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism, is the primary source of Burmese loanwords.<ref name=":10" /> British colonisation also introduced numerous English loanwords to the Burmese lexicon.<ref name=":11">{{Citation |last=Jenny |first=Mathias |title=25 The national languages of MSEA: Burmese, Thai, Lao, Khmer, Vietnamese |date=2021-08-09 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110558142-025/html |work=The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia |pages=599–622 |editor-last=Sidwell |editor-first=Paul |publisher=De Gruyter |doi=10.1515/9783110558142-025 |isbn=978-3-11-055814-2 |access-date=2022-08-22 |editor2-last=Jenny |editor2-first=Mathias}}</ref> As a lingua franca, Burmese has been the source and intermediary of loanwords to other [[Lolo-Burmese languages]] and major regional languages, including Shan, Kachin, and Mon.<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kurabe |first=Keita |date=2016-12-31 |title=Phonology of Burmese loanwords in Jinghpaw |url=https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/handle/2433/219015 |journal=京都大学言語学研究 |volume=35 |pages=91–128 |doi=10.14989/219015 |issn=1349-7804}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Burmese-Pali Manuscript Wellcome L0067946.jpg|thumb|[[Niddesa|Mahāniddesa]], a Buddhist manuscript written in the Burmese script]] |

|||

The Burmese language has a longstanding literary tradition and tradition of literacy.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fen |first=Wong Soon |date=April 2005 |title=English in Myanmar |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0033688205053485 |journal=RELC Journal |language=en |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=93–104 |doi=10.1177/0033688205053485 |issn=0033-6882}}</ref> Burmese is the fifth Sino-Tibetan language to develop a writing system, after [[Chinese characters|Chinese]], [[Tibetan script|Tibetan]], [[Pyu language (Sino-Tibetan)|Pyu]], and [[Tangut script|Tangut]]. The oldest surviving written Burmese document is the [[Myazedi inscription]], which is dated to 1113.<ref name=":2" /> The [[Burmese script]] is an [[Abugida|Indic writing system]], and modern Burmese orthography retains features of Old Burmese spellings.<ref name=":12">{{Citation |last=Jenny |first=Mathias |title=36 Writing systems of MSEA |date=2021-08-09 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110558142-036/html |work=The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia |pages=879–906 |editor-last=Sidwell |editor-first=Paul |publisher=De Gruyter |doi=10.1515/9783110558142-036 |isbn=978-3-11-055814-2 |access-date=2022-08-22 |editor2-last=Jenny |editor2-first=Mathias}}</ref> The Shan, Ahom, Khamti, Karen, and Palaung scripts are descendants of the Burmese script.<ref name=":12" /> |

|||

Standard Burmese is based on the language spoken in Yangon and Mandalay, although more distinct Burmese dialects, including [[Yaw dialect|Yaw]], [[Tavoyan dialects|Dawei]] (Tavoyan), [[Myeik dialect|Myeik]], [[Palaw]], [[Intha-Danu language|Intha-Danu]], [[Arakanese language|Arakanese]] (Rakhine), and [[Taungyo]], emerge in more peripheral and remote areas of the country.<ref name=":13">{{Citation |last=Hill |first=Nathan W. |title=7 Scholarship on Trans-Himalayan (Tibeto-Burman) languages of South East Asia |date=2021-08-09 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110558142-007/html |work=The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia |pages=111–138 |editor-last=Sidwell |editor-first=Paul |publisher=De Gruyter |doi=10.1515/9783110558142-007 |isbn=978-3-11-055814-2 |access-date=2022-08-22 |editor2-last=Jenny |editor2-first=Mathias}}</ref> These dialects differ from Standard Burmese in pronunciation and lexical choice, not grammar.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Frawley |first=William |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sl_dDVctycgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=International+Encyclopedia+of+Linguistics+(2+ed.)+%C2%A0&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&ovdme=1&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj5opyW9dn5AhUFQjABHfGOBXQQ6AF6BAgKEAM#v=onepage&q=International%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Linguistics%20(2%20ed.)%20%C2%A0&f=false |title=International Encyclopedia of Linguistics |date=May 2003 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-19-513977-8 |edition=2nd |language=en |chapter=Burmese}}</ref> For instance, Arakanese retains the {{IPA|/ɹ/}} sound, which had merged into the {{IPA|/j/}} sound in standard Burmese between the 1700s and 1800s (although the former sound is still represented in modern Burmese orthography), while the Dawei and Intha dialects retain a medial {{IPA|/l/}} that had disappeared in standard Burmese orthography by the 1100s.<ref name=":13" /> The pronunciation distinction is reflected in the word for 'ground,' which is pronounced {{IPA|/mjè/}} in standard Burmese, {{IPA|/mɹì/}} in Arakanese (both spelt {{my|မြေ}}), and {{IPA|/mlè/}} in Dawei (spelt {{my|မ္လေ}}).{{NoteTag|Unlike Standard Burmese, Rakhine also merges the {{IPA|/i/}} and {{IPA|/e/}} vowels.}} |

|||

==Culture and society== |

==Culture and society== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Noviciation_Ceremony.jpg|thumb|A young boy dressed in royal attire ceremonially re-enacts the Buddha's life, in the [[shinbyu]] rite of passage.]] |

||

Bamar culture, including traditions, literature, cuisine, music, dance, and theatre, has been significantly enriched by Theravada Buddhism and by historical contact and exchange with neighbouring societies, and more recently shaped by Myanmar's colonial and post-colonial history. |

|||

Bamar culture has been influenced by those of neighboring countries. This is manifested in its language, cuisine, music, dance and theatre. The arts, particularly literature, have historically been influenced by the local form of the [[Animism|animistic]] religion and [[Theravada Buddhism]]. In a traditional village, the monastery is the centre of cultural life. Monks are venerated and supported by the lay people. [[Rites of passage]] are also of cultural importance to the Bamar. These include ''[[shinbyu]]'' ({{my|ရှင်ပြု}}), a novitiate ceremony for Buddhist boys and ''nar tha'' ({{my|နားထွင်း}}), an ear-piercing ceremony for girls. Burmese culture is most evident in villages where local festivals are held throughout the year, the most important being the [[pagoda festival]]. Many villages have a guardian [[Nat (spirit)|nat]] and superstition and taboos are commonplace. |

|||

A pivotal Bamar societal value is the concept of [[Anade|''anade'']], which is manifested by very strong inhibitions (e.g., hesitation, reluctance, restraint, or avoidance) against asserting oneself in human relations based on the fear that it will offend someone or cause someone to [[lose face]], or become embarrassed, or be of inconvenience.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Myanmar Personality |url=http://www.myanmar.gov.mm/Perspective/persp2001/1-2001/nar.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20070822213342/http://www.myanmar.gov.mm/Perspective/persp2001/1-2001/nar.htm |archive-date=22 August 2007 |access-date=22 May 2022 |website=www.myanmar.gov.mm}}</ref> Charity and almsgiving are also central to Bamar society, best exemplified by Myanmar's consistent presence among the world's most generous countries according to the [[World Giving Index]], since rankings were first introduced in 2013.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Pequenino |first=Karla |date=2016-10-26 |title=Myanmar again named world's most generous country |url=https://www.cnn.com/2016/10/26/world/world-generosity-index-caf-2016/index.html |access-date=2022-09-11 |website=CNN |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=June 2021 |title=CAF World Giving Index 2021 |url=https://www.cafonline.org/docs/default-source/about-us-research/cafworldgivingindex2021_report_web2_100621.pdf |website=Charities Aid Foundation}}</ref> |

|||

===Traditional dress=== |

|||

The Bamar traditionally wore sarongs. Women wear a type of sarong known as ''htamain'' ({{my|ထဘီ}}), while men wear a sarong sewn into a tube, called a ''longyi'' (လုံချည်)<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=https://consult-myanmar.com/2015/03/09/myanmars-traditional-fashion-choices-endure/|title=Myanmar's Traditional Fashion Choices Endure|website=consult-myanmar.com|language=en-US|access-date=2018-07-09}}</ref> or, more formally, a single long piece wrapped around the hips, known in Burmese as a ''paso'' ({{my|ပုဆိုး}}). Formal attire often consists of gold jewelry, silk scarves and jackets. On formal occasions, men often wear cloth turbans called ''[[gaung baung]]'' ({{my|ခေါင်းပေါင်း}}) and [[Mandarin collar|Mandarin collared jackets]] called ''taikpon'' ({{my|တိုက်ပုံ}}), while women wear blouses. |

|||

The Bamar customarily recognise [[Twelve Auspicious Rites]], which are a series of [[Rite of passage|rites of passage]]. Among these rites, the naming of the child, first feeding, ear-boring for girls, Buddhist ordination ([[shinbyu|''shinbyu'']]) for boys, and [[Marriage in Myanmar|wedding]] rites are the most widely-practiced today.<ref name=":32">{{Cite web |title=မြန်မာတွင် လောကီမင်္ဂလာလေးမျိုးသာပြုလုပ်တော့ဟု ဗြိတိန်မနုဿဗေဒပညာရှင်ဆို |url=https://7day.news/detail?id=41102 |access-date=2021-01-17 |website=7Day News - ၇ ရက်နေ့စဉ် သတင်း |language=my}}</ref> |

|||

Both genders wear velvet sandals called ''[[Hnyat-phanat|gadiba phanat]]'' ({{my|ကတ္တီပါဖိနပ်}}, also called ''Mandalay phanat''), although leather, rubber and plastic sandals ({{my|ဂျပန်ဖိနပ်}}, lit. Japanese shoes) are also worn. In cities and urban areas, Western dress, including T-shirts, jeans and sports shoes or trainers, has become popular, especially among the younger generation.<ref name=":1" /> Talismanic tattoos, earrings, and long hair tied in a knot were once common among Bamar men, but have ceased to be fashionable since after World War II; men in shorts and sporting ponytails, as well as both sexes with bleached hair, have made their appearance in [[Yangon]] and [[Mandalay]] more recently, especially in the anything-goes atmosphere of the Burmese New Year holiday known as [[Thingyan]]. |

|||

=== Literature === |

|||

Bamar people of both sexes and all ages also wear ''[[thanaka]]'', especially on their faces, although the practice is largely confined to women, children, and young, unmarried men. Western makeup and cosmetics have long enjoyed a popularity in urban areas.<ref name=":1" /> However, thanaka is not exclusively worn by the Bamar, as many other ethnic groups throughout Burma utilize this cosmetic. |

|||

{{Main|Burmese literature}} |

|||

[[File:19th-century Ramayana manuscript, Rama Thagyin, Myanmar version, Ravana (Dathagiri) sends Gambi as golden deer (Shwethamin) to deceive Sita (Thida).jpg|thumb|A 19th-century Burmese manuscript depicting a scene from the [[Ramayana]] epic.]]{{Expand section|date=September 2022}} |

|||

===Cuisine=== |

|||

Burmese literature has a longstanding history, spanning religious and secular genres. [[Burmese chronicles]] and historical memoirs called ''ayedawbon'' comprise the basis of the Bamar's pre-colonial historical writing traditions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wade |first=Geoff |date=2012-03-29 |title=Southeast Asian Historical Writing |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/4818/chapter/147118654 |language=en |doi=10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199219179.003.0007}}</ref> |

|||

[[Burmese cuisine|Bamar cuisine]] contains many regional elements, such as [[stir frying]] techniques and [[curries]] which can be hot but lightly spiced otherwise, almost always with [[fish paste]] as well as onions, garlic, ginger, dried chili and turmeric. Rice ({{my|ထမင်း}} ''htamin'') is the staple, although [[noodles]] ({{my|ခေါက်ဆွဲ}}, ''hkauk swè''), [[salad]]s ({{my|အသုပ်}}, ''a thouk''), and breads ({{my|ပေါင်မုန့်}}, ''paung mont'') are also eaten. Burmese typical diet consists of rice as the main dish along with various curry dishes. [[Green tea]] is often the beverage of choice, but tea is also traditionally pickled and eaten as a salad called ''[[lahpet]]''. The best-known dish of Bamar origin is ''[[mohinga]]'', rice noodles in a fish broth. It is available in most parts of the region, also considered as the national dish of [[Myanmar]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.foodrepublic.com/2017/02/22/burmese-food-primer/|title=Burmese Food Primer: Essential Dishes To Eat in Myanmar|date=2017-02-22|work=Food Republic|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en-US}}</ref> Dishes from other ethnic minorities such as the [[Shan people|Shan]], Chinese and Indian are also consumed. |

|||

=== |

=== Calendar === |

||

{{Main|Burmese calendar}} |

|||

Traditional [[music of Myanmar]] consists of an orchestra mainly of percussion and wind instruments but the ''[[saung|saung gauk]]'' ({{my|စောင်းကောက်}}), a boat-shaped harp, is often symbolic of the Bamar. Other traditional instruments include ''[[pattala]]'' (Burmese [[xylophone]]), ''walatkhok'', ''lagwin'' and ''[[Pat waing|hsaingwaing]]''. Traditional Bamar dancing is similar to Thai dancing. Puppetry is also a popular form of entertainment and is often performed at ''pwé''s, which is a generic term for shows, celebrations and festivals. In urban areas, movies from both [[Bollywood]] and Hollywood have long been popular, but more recently Korean and Chinese films, especially DVDs, have become increasingly popular. |

|||

The traditional [[Burmese calendar]] is a lunisolar calendar that was widely adopted throughout mainland Southeast Asia, including Siam and Lan Xang, until the late 19th century. Similar to neighbouring Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, ''[[Thingyan]]'', which is held during the month of April, marks the beginning of the Burmese New Year.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2017-06-16 |title=HOW THE BURMESE CELEBRATE NEW YEAR FESTIVAL? |language=vi-VN |work=EN – To travel is to live |url=https://idealtravelasia.com/burmese-celebrate-new-year-festival/ |access-date=2018-07-09}}</ref> Several Buddhist full moon days, including the full moon days of [[Tabaung]] (for [[Māgha Pūjā|Magha Puja]]), [[Kason]] (for [[Vesak]]), [[Waso]] (start of the [[Vassa|Buddhist lent]]), Thadingyut (end of the Buddhist lent), and [[Tazaungmon]] (start of [[Kathina]]), are [[Public holidays in Myanmar|national holidays]]. Full moon days also tend to coincide with numerous [[pagoda festival]]s, which typically commemorate events in a pagoda's history. |

|||

===Festivals=== |

|||

Buddhist festivals and holidays are widely celebrated by the Bamar people. ''[[Thingyan]]'', the Water Festival, which marks the beginning of the Burmese New Year in April, is one such example.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://idealtravelasia.com/burmese-celebrate-new-year-festival/|title=HOW THE BURMESE CELEBRATE NEW YEAR FESTIVAL?|date=2017-06-16|work=EN – To travel is to live|access-date=2018-07-09|language=vi-VN}}</ref> ''[[Thadingyut Festival|Thadingyut]]'', which marks the end of the [[Vassa|Buddhist lent]], is celebrated with the Festival of Lights in October. ''[[Kathina]]'' or robe offering ceremony for monks is held at the start of Lent in July and again in November. |

|||

=== |

===Cuisine=== |

||

{{Main|Burmese cuisine}} |

|||

[[File:Nat-ein.jpg|thumb|A ''[[nat ein]]'' in Downtown Yangon]] |

|||

[[File:Pickled_tea_(lahpet).JPG|thumb|''Laphet'', served in a traditional lacquer tray called ''laphet ok''.]] |

|||

The majority of the Bamar follow a [[syncretism]] of the native [[Burmese folk religion]] and [[Theravada|Theravada Buddhism]]. People are expected to keep the basic [[five precepts]] and practise ''[[dāna]]'' "charity", ''sīla'' "[[Buddhist ethics]]" and ''[[vipassanā]]'' "meditation". Most villages have a monastery and often a [[stupa]] maintained and supported by the villagers. Annual [[pagoda festival]]s usually fall on a full moon and robe offering ceremonies for [[bhikkhu]]s are held both at the beginning and after the [[Vassa]]. This coincides with the [[monsoon]]s, during which the [[uposatha]] is generally observed once a week. |

|||

[[White rice]] is the staple of the Bamar diet, reflecting a millennium of continuous rice cultivation in Burmese-speaking areas. [[Burmese curry|Burmese curries]], which are made with a curry paste of onions, garlic, ginger, paprika, and turmeric, alongside [[Burmese salads]], soup, cooked vegetables, and [[ngapi]] (fermented shrimp or fish paste) traditionally accompany rice for meals. Noodles and [[Indian bread|Indian breads]] are also eaten.<ref name=":02">{{Cite book |last=Duguid |first=Naomi |url= |title=Burma: Rivers of Flavor |date=2012-11-27 |publisher=Random House of Canada |isbn=978-0-307-36217-9 |location= |pages= |language=en}}</ref> The Bamar traditionally drink [[green tea]], and also eat pickled tea leaves, called ''[[lahpet]]'', which plays an important role in ritual culture.<ref>{{Cite book |last=van Driem |first=George L. |url=https://brill.com/view/title/36412 |title=The Tale of Tea: A Comprehensive History of Tea from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day |date=2019-01-01 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-39360-8 |doi=10.1163/9789004393608_002}}</ref> Burmese cuisine is also known for its variety of [[Mont (food)|''mont'']], a profuse variety of sweet desserts and savory snacks, including [[Burmese fritters]]. The best-known dish of Bamar origin is ''[[mohinga]]'', rice noodles in a fish broth. It is available in most parts of the region, also considered as the national dish of [[Myanmar]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.foodrepublic.com/2017/02/22/burmese-food-primer/|title=Burmese Food Primer: Essential Dishes To Eat in Myanmar|date=2017-02-22|work=Food Republic|access-date=2018-07-09|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Hsun_laung,_Mandalay,_Myanmar.JPG|thumb|Buddhist monks in Mandalay receive food alms from a ''[[htamanè]]'' hawker during their daily alms round (ဆွမ်းလောင်းလှည့်).]] |

|||

Burmese cuisine has been significantly enriched by contact and trade with neighboring kingdoms and countries well into modern times. The [[Columbian exchange]] in the 15th and 16th centuries introduced key ingredients into the Burmese culinary repertoire, including [[Tomato|tomatoes]], [[Chili pepper|chili peppers]], [[Peanut|peanuts]], and [[Potato|potatoes]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cumo |first=Christopher |url= |title=The Ongoing Columbian Exchange: Stories of Biological and Economic Transfer in World History: Stories of Biological and Economic Transfer in World History |date=2015-02-25 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-61069-796-5 |location= |pages= |language=en}}</ref> While record-keeping of pre-colonial culinary traditions is scant, food was and remains deeply intertwined with Bamar religious life, exemplified in the giving of food alms ([[dāna]]), and communal feasts called ''[[satuditha]]'' and ''ahlu pwe'' (အလှူပွဲ). |

|||

===Music=== |

|||

Children were educated by monks before secular state schools came into being. A ''[[shinbyu]]'' ceremony by which young boys become novice monks for a short period is considered the most important duty of Buddhist parents. Christian missionaries had made little impact on the Bamar despite the popularity of missionary schools in cities.{{citation needed|date=May 2020}} |

|||

{{Main|Music of Myanmar}} |

|||

[[File:Wyne_Lay_playing_a_Saung.JPG|thumb|Burmese singer [[Wyne Lay]] plays the ''saung'' during a musical performance.]] |

|||

Traditional Bamar music is subdivided into folk and classical traditions. Folk music is typically accompanied by the [[hsaing waing|''hsaing waing'']], a musical ensemble featuring a variety of gongs, drums and other instruments, including a drum circle called [[pat waing|''pat waing'']], which is the ensemble's centrepiece.<ref name="hsaing">{{cite journal |last=Garifas |first=Robert |year=1985 |title=The Development of the Modern Burmese Hsaing Ensemble |journal=Asian Music |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=1–28 |doi=10.2307/834011 |jstor=834011}}</ref> Classical music descends from Burmese royal court traditions. The [[Mahāgīta]] constitutes the entire corpus of Burmese classical music, which is often accompanied by a small [[chamber music]] ensemble that features a distinct set of instruments, such as a harp called [[Saung|saung gauk]], bell and clapper, and a xylophone called [[pattala]]. |

|||

===Traditional dress=== |

|||

The Bamar practise Buddhism along with ''[[nat (spirit)|Nat]]'' worship which predated Buddhism. It involves rituals relating to a pantheon of 37 Nats or spirits designated by King [[Anawrahta]], although many minor nats are also worshipped. In villages, many houses have outdoors altars to honor nats, called ''nat ein'' ({{my|နတ်အိမ်}}), in addition to one outside the village known as ''nat sin'' ({{my|နတ်စင်}}) often under a bo tree (''[[Ficus religiosa]]''). Indoors in many households, one may find a coconut called ''nat oun'' up the main post for the ''Eindwin Min Mahagiri'' ({{my|အိမ်တွင်းမင်းမဟာဂိရိ}}, lit. "Indoor Lord of the Great Mountain"), considered one of the most important of the Nats. |

|||

{{See|Burmese clothing}} |

|||

[[File:Mandalay_belle.jpg|thumb|A Mandalay woman dressed in a trailing ''htamein'' commonly worn in until the early 20th century.]] |

|||

The Bamar traditionally wear [[Sarong|sarongs]] called [[Longyi|''longyi'']], an ankle-length cylindrical skirt that is wrapped at the waist.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Myanmar's Traditional Fashion Choices Endure |url=https://consult-myanmar.com/2015/03/09/myanmars-traditional-fashion-choices-endure/ |access-date=2018-07-09 |website=consult-myanmar.com |language=en-US}}</ref> The modern form of the ''longyi'' was popularised during the British colonial period, and replaced the much lengthier ''paso'' (လုံချည်) and ''htamein'' ({{my|ထဘီ}}) of the pre-colonial era. The indigenous [[Acheik|''acheik'']] silk textile, known for its colorful wave-like patterns, is closely associated with the Bamar. |

|||

Formal attire for men includes a longyi accompanied by a jacket called ''taikpon'' ({{my|တိုက်ပုံ}}), which similar to the Manchu [[Magua (clothing)|magua]], and a cloth turban called ''[[gaung baung]]'' ({{my|ခေါင်းပေါင်း}}).<ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |date= |title=The origin of today's Myanmar men's outfit |url=https://www.lostfootsteps.org/en/history/the-origin-of-todays-myanmar-mens-outfit |url-status=live |archive-url= |archive-date= |access-date=2020-12-07 |website=Lost Footsteps |language=en}}</ref> Velvet sandals called ''[[Hnyat-phanat|gadiba phanat]]'' ({{my|ကတ္တီပါဖိနပ်}}, also called ''Mandalay phanat''), are worn as formal footwear by both men and women. |

|||

The term "Bamar" is sometimes used to refer to both the practice of Buddhism as well as the ethnic identity. [[Islam in Myanmar|Bamar Muslims]], however, practise Islam and claim ethnic Bamar heritage and culture in all matters other than religion.<ref name="Ayako">{{cite journal | url=http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/Formation_of_the_Concept_of_Myanmar_Muslims_as_Indigenous-en.pdf | title=The Formation of the Concept of Myanmar Muslims as Indigenous Citizens: Their History and Current Situation | author=Ayako, Saito | journal=The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies | year=2014 | issue=32 | pages=25–40}}</ref> |

|||

Bamar people of both sexes and all ages also apply ''[[thanaka|thanakha]]'', a paste ground from the fragrant wood of select tree species, on their skin, especially on their faces.<ref name="yeni">{{cite news |last=Yeni |date=5 August 2011 |title=Beauty That's More Than Skin Deep |work=The Irrawaddy |url=http://irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=21842 |url-status=dead |accessdate=7 August 2011 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110806235130/http://irrawaddy.org/article.php?art_id=21842 |archivedate=6 August 2011}}</ref> In modern times, the practice is now largely confined to women, children, and young, unmarried men. The use of ''thanakha'' is not unique to by the Bamar; many other Burmese ethnic groups also utilize this cosmetic. Western makeup and cosmetics have long enjoyed a popularity in urban areas.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

===Naming=== |

|||

{{main|Burmese names}} |

|||

===Personal names=== |

|||

In the past, the Bamar typically had shorter names, usually limited to one or two syllables. However, the trend of adopting longer names (four or five for females and three for males) has become popular. Bamar names also frequently make use of [[Pali]]-derived loan words. Bamar people typically use the day of birth (traditional 8-day calendar, which includes ''[[Rahu|Yahu]]'', Wednesday afternoon) as the basis for naming, although this practice is not universal.{{sfn|Scott|1882|p=4}} Letters from groups within the [[Burmese alphabet]] are designated to certain days, from which the Bamar choose names.{{sfn|Scott|1882|p=4-6}} |

|||

{{main|Burmese names}} |

|||

[[File:PICT0032 Burma Yangon Shwédagon Temple Planetary Post (7506306786).jpg|thumb|The Tuesday planetary post at [[Shwedagon Pagoda]], which is customarily visited by Tuesday-born devotees.]] |

|||

The Bamar possess a single personal name, and do not have family names or surnames.<ref name=":15">{{Cite web |title=Myanmar (Burmese) Culture |url=http://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/burmese-myanmar-culture/burmese-myanmar-culture-naming |access-date=2022-08-22 |website=Cultural Atlas |language=en}}</ref> Burmese names typically incorporate a mix of native and Pali words that symbolise positive virtues, with female names tending to signify beauty, flora, and family values, and male names connoting strength, bravery, and success.<ref name=":15" /> Personal names are prefixed with honorifics based on one's relative gender, age, and social status.<ref name=":16">{{Cite web |last=Khaing |first=Daw Mi Mi |date=1958-02-01 |title=Burmese Names |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1958/02/burmese-names/306818/ |access-date=2022-08-22 |website=The Atlantic |language=en}}</ref> For instance, a Bamar male will advance from the honorific of "Maung" to "Ko" as he approaches middle adulthood, and from "Ko" to "U' as he approaches [[old age]].<ref name=":16" /> |

|||

A common Bamar naming scheme uses a child's day of birth to assign the first letter of their name, reflecting the importance of one's day of birth in [[Burmese zodiac|Burmese astrology]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ma Tin Cho Mar |date=2020 |title=ONOMASTIC TREASURE OF BURMESE PERSONAL NAMES AND NAMING PRACTICES IN MYANMAR |journal=Isu Dalam Pendidikan |publisher=University of Malaya |issue=43}}</ref> The traditional [[Burmese calendar]] includes ''[[Rahu|Yahu]]'', which is Wednesday afternoon. |

|||

They are chosen as follows: |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

{|class="wikitable" |

||

!Day |

!Day of birth |

||

!Letters |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Monday<br/>({{my|တနင်္လာ}}) |

|||

| {{my|က}} (ka), {{my|ခ}} (kha), {{my|ဂ}} (ga), {{my|ဃ}} (gha), {{my|င}} (nga) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Tuesday<br/>({{my|အင်္ဂါ}}) |

|||

| {{my|စ}} (sa), {{my|ဆ}} (hsa), {{my|ဇ}} (za), {{my|ဈ}} (za), {{my|ည}} (nya) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Wednesday<br/>({{my|ဗုဒ္ဓဟူး}}) |

|||

| {{my|လ}} (la), {{my|ဝ}} (wa) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Rahu|Yahu]]<br/>({{my|ရာဟု}}) |

|||

| {{my|ယ}} (ya), {{my|ရ}} (ya, ra) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Thursday<br/>({{my|ကြာသပတေး}}) |

|||

| {{my|ပ}} (pa), {{my|ဖ}} (hpa), {{my|ဗ}} (ba), {{my|ဘ}} (ba), {{my|မ}} (ma) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Friday<br/>({{my|သောကြာ}}) |

|||

| {{my|သ}} (tha), {{my|ဟ}} (ha) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Saturday<br/>({{my|စနေ}}) |

|||

| {{my|တ}} (ta), {{my|ထ}} (hta), {{my|ဒ}} (da), {{my|ဓ}} (da), {{my|န}} (na) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Sunday<br/>({{my|တနင်္ဂနွေ}}) |

|||

| {{my|အ}} (a) |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

== |

== Religions == |

||

{{See|Buddhism in Myanmar|Burmese folk religion}}[[File:Buddha_Day.jpg|thumb|Buddhist devotees converge on a Bodhi tree in preparation for watering, a traditional activity during the Full Moon Day of Kason.]]The Bamar traditionally practice a syncretic blend of [[Theravada|Theravada Buddhism]] and indigenous [[Burmese folk religion]], the latter of which involves the recognition and veneration of spirits called [[Nat (deity)|''nat'']], and pre-dates the introduction of Theravada Buddhism. These two faiths play an important role in Bamar cultural life. A minority of Bamar practice other world religions, including Islam and Christianity. Among them, [[Islam in Myanmar|Bamar Muslims]] (previously known as Zerbadees or Pati), are the descendants of interracial marriages between Indian Muslim fathers and Bamar Buddhist mothers, and self-identify as Bamar.<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last=Khin Maung Yin |date=2005 |title=Salience of Ethnicity among Burman Muslims: A Study in Identity Formation |journal=Intellectual Discourse |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=161-179}}</ref><ref name="Ayako">{{cite journal |author=Ayako, Saito |year=2014 |title=The Formation of the Concept of Myanmar Muslims as Indigenous Citizens: Their History and Current Situation |url=http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/Formation_of_the_Concept_of_Myanmar_Muslims_as_Indigenous-en.pdf |journal=The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies |issue=32 |pages=25–40}}</ref>{{NoteTag|The term Zerbadee was first used in the 1891 Burma Census, and may derive from the Persian phrase zer bad, which means 'below the wind' or 'land of the east.'}} |

|||

Theravada Buddhism is closely intertwined with the Bamar, having been the predominant faith among Burmese speakers since the 11th century, during the [[Pagan Kingdom|Pagan]] dynasty. Modern-day Bamar Buddhism is typified by the observance of basic [[five precepts]] and the practice of ''[[dāna]]'' (charity), ''sīla (''[[Buddhist ethics]]) and ''bhavana'' (meditation). Village life is centred at Buddhist monasteries called ''[[kyaung]]'', which serve as community centres and address the community's spiritual needs.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Griffiths |first=Michael P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Eta_DwAAQBAJ&newbks=0&printsec=frontcover&pg=PT25&dq=bamar+buddhism+centred+monastery&hl=en |title=Community Welfare Organisations in Rural Myanmar: Precarity and Parahita |date=2019-11-21 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-76743-8 |language=en}}</ref> Buddhist Sabbath days called [[uposatha]], which follow the moon's phases (i.e., new, waxing, full, waning), are observed by more devout Buddhists.[[File:Nat_oun.JPG|thumb|A coconut, called ''on-daw'', is traditionally hung on the southwest post in a house, symbolising the household guardian ''nat.'']]The Bamar also profess a belief in guardian ''nats,'' particularly the veneration of [[Mahagiri]], the household guardian ''nat.<ref name=":19" />'' Bamar households traditionally maintain a shrine, which holds a long-stemmed coconut called ''on-daw'' (အုန်းတော်), symbolic of Mahagiri.''<ref name=":19" />'' The shrine is traditionally placed at the home's main southwest pillar (called ''yotaing'' or ရိုးတိုင်). The expression of Burmese folk religion is very localised; the Bamar in Upper Myanmar and urban areas tend to propitiate the Thirty-Seven Min, a pantheon of ''nats'' who are intimately linked to the pre-colonial royal court.<ref name=":19" /> Meanwhile, the Bamar in Lower Myanmar tend to propitiate other local or guardian ''nats'' like [[Bago Medaw]].<ref name=":19" /> [[Spirit house|Spirit houses]] called ''nat ein'' ({{my|နတ်အိမ်}}) or ''nat sin'' ({{my|နတ်စင်}}) are commonly found in Bamar areas. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Burmese people]] |

|||

* [[Culture of Myanmar]] |

* [[Culture of Myanmar]] |

||

* [[Demographics of Myanmar]] |

* [[Demographics of Myanmar]] |

||

| Line 201: | Line 168: | ||

* [[Rakhine people]] |

* [[Rakhine people]] |

||

* [[Burmese mythology]] |

* [[Burmese mythology]] |

||

== Notes == |

|||

{{NoteFoot}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 213: | Line 183: | ||

*{{cite book | author=Tsaya | author-link=Tsaya | year=1886 | title=Myam-Ma, The Home of the Burman | publisher=Thacker, Spink and Co. | location =Calcutta | pages = 36–37 | url=http://dlxs.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?type=simple;c=sea;cc=sea;sid=40c565a47750ac05acd1a56fe2bec38b;rgn=author;q1=Tsaya;view=toc;subview=short;sort=occur;start=1;size=25;idno=sea314}} |

*{{cite book | author=Tsaya | author-link=Tsaya | year=1886 | title=Myam-Ma, The Home of the Burman | publisher=Thacker, Spink and Co. | location =Calcutta | pages = 36–37 | url=http://dlxs.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?type=simple;c=sea;cc=sea;sid=40c565a47750ac05acd1a56fe2bec38b;rgn=author;q1=Tsaya;view=toc;subview=short;sort=occur;start=1;size=25;idno=sea314}} |

||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

==External links== |

|||

*[https://archive.org/details/TheSilkenEast The Silken East – A Record of Life and Travel in Burma by V. C. Scott O'Connor 1904] |

|||

*{{cite web |first=Kyi |last=Wai |title=Burmese Women's Hair in Big Demand |url=http://www.irrawaddy.org/Multimedia/Hair/index.php |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071111203543/http://www.irrawaddy.org/Multimedia/Hair/index.php |archive-date=2007-11-11 |publisher=[[The Irrawaddy]] |date=2007-06-15}} |

|||

{{Ethnic groups in Burma}} |

|||

{{Ethnic groups in Cambodia}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Bamar people]] |

|||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Myanmar]] |

|||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Thailand]] |

|||

[[Category:Sino-Tibetan-speaking people]] |

|||

[[Category:Buddhist communities of Myanmar]] |

|||

[[Category:Southeast Asian people]] |

|||

Revision as of 23:03, 11 September 2022

ဗမာလူမျိုး | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Burmese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Theravada Buddhism and Burmese folk religion Minority Christianity and Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Danu, Intha, Rakhine, Marma, Achang and other Sino-Tibetan peoples |

The Bamar (Burmese: ဗမာလူမျိုး; MLCTS: ba. ma lu myui:, IPA: [bəmà lùmjó]; also known as the Burmans) are a Sino-Tibetan ethnic group native to Myanmar (formerly Burma) in Southeast Asia. With approximately 35 million people, the Bamar make up the largest ethnic group in Myanmar, constituting 68% of the country's population.[1] The geographic homeland of the Bamar is the Irrawaddy River basin. Burmese is the native language of the Bamar, as well as the national language and lingua franca of Myanmar.[1]

Ethnonyms

In the Burmese language, Bamar (ဗမာ, also transcribed Bama) and Myanmar (မြန်မာ, also transliterated Mranma and transcribed Myanma) have historically been interchangeable endonyms.[2] Burmese is a diglossic language; "Bamar" is the diglossic low form of "Myanmar," which is the diglossic high equivalent.[3] The term "Myanmar" is extant to the early 1100s, first appearing on a stone inscription, where it was used as a cultural identifier, and has continued to be used in this manner.[4] From the onset of British colonial rule to the Japanese occupation of Burma, "Bamar" was used in Burmese to refer to both the country and its majority ethnic group.[5] Since the country achieved independence in 1948, "Myanmar" has been officially used to designate both the nation-state and its official language, while "Bamar" has been used to designate the majority ethnic group, especially in written contexts.[5] In spoken usage, "Bamar" and "Myanmar" remain interchangeable, especially with respect to referencing the language and country.[5]

In the English language, the Bamar are known by a number of exonyms, including Burmans and Burmese, both of which were interchangeably used by the British.[note 1] In June 1989, in an attempt to indigenise both the country's place names and ethnonyms, the military government changed the official English names of the country (from Burma to Myanmar), the language (from Burmese to Myanmar), and the country's majority ethnic group (from Burmans to Bamar).[6][7][8]

Ancestral origins

The Bamar's northern origins are evidenced by the extant distribution of Burmish languages to the north of the country, and the fact that taung (တောင်), the Burmese word for 'south' also means 'mountain,' which suggests that at one point ancestors of the Bamar lived north of the Himalayas.[9] Until a thousand years ago, ancestors of the Bamar and Yi were much more widespread across Yunnan, Guizhou, southern Sichuan, and northern Burma.[note 2] During the Han dynasty in China, Yunnan was ruled primarily by the Burmese-Yi speaking Dian and Yelang kingdoms. During the Tang dynasty in China, Yunnan and northern Burma were ruled by the Burmese-Yi speaking Nanzhao kingdom.