Low back pain: Difference between revisions

→Differential diagnosis: c/e, accurify to source |

diff diag - add henschke 2013 for vertebral fracture |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

===Differential diagnosis=== |

===Differential diagnosis=== |

||

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from [[radiculopathy]] and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using [[diagnostic imaging]] or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> In addition, the successful finding of some red flags comes with a high risk of a false-positive diagnosis of spinal malignancy, and evidence does not support their use for making such |

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from [[radiculopathy]] and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using [[diagnostic imaging]] or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> In addition, the successful finding of some red flags comes with a high risk of a false-positive diagnosis of spinal malignancy or vertebral fracture, and evidence does not clearly support their use for making such diagnoses, especially ones based on the presence of only one red flag.<ref name=henschke_2013_spinmal/><ref name=henschke_2013_vertfrac/> With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain typically are treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the underlying cause.<ref name=koes_2010/><ref name=casazza_2012/> |

||

===Imaging=== |

===Imaging=== |

||

| Line 255: | Line 255: | ||

<ref name=henschke_2009>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, ''et al.'' |title=Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=60 |issue=10 |pages=3072–80 |year=2009 |month=October |pmid=19790051 |doi=10.1002/art.24853 |url=}}</ref> |

<ref name=henschke_2009>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, ''et al.'' |title=Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=60 |issue=10 |pages=3072–80 |year=2009 |month=October |pmid=19790051 |doi=10.1002/art.24853 |url=}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= |

<ref name=henschke_2013_spinmal>{{cite journal |author=Henschke N, Maher CG, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L |title=Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=2 |issue= |pages=CD008686 |year=2013 |pmid=23450586 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008686.pub2 |url=}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=henschke_2013_vertfrac>{{cite journal |author=Williams CM, Henschke N, Maher CG, ''et al.'' |title=Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in patients presenting with low-back pain |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=1 |issue= |pages=CD008643 |year=2013 |pmid=23440831 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD008643.pub2 |url=}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=hoy_2012>{{cite journal |author=Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, ''et al.'' |title=A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=2028–37 |year=2012 |month=June |pmid=22231424 |doi=10.1002/art.34347 |url=}}</ref> |

<ref name=hoy_2012>{{cite journal |author=Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, ''et al.'' |title=A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=2028–37 |year=2012 |month=June |pmid=22231424 |doi=10.1002/art.34347 |url=}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:05, 4 June 2013

| Low back pain | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery, rehabilitation |

Low back pain or lumbago /lʌmˈbeɪɡoʊ/ is a common musculoskeletal disorder affecting 80% of people at some point in their lives. In the United States it is the most common cause of job-related disability, a leading contributor to missed work, and the second most common neurological ailment — only headache is more common.[1] It can be either acute, subacute or chronic in duration. With conservative measures, the symptoms of low back pain typically show significant improvement within a few weeks from onset.

Classification

Lower back pain may be classified by the duration of symptoms as acute, subacute and chronic. Within these classifications, there is no agreement across medical organizations for the specific duration of symptoms, but generally pain lasting less than six weeks is classified as acute, pain lasting six to 12 weeks is subacute, and more than 12 weeks is chronic.[2]

Cause

The majority of lower back pain is referred to as non specific low back pain and does not have a definitive cause.[3] It is believed to stem from benign musculoskeletal problems such as muscle or soft tissues sprain or strains.[1] This is particularly true when the pain arose suddenly during physical loading of the back, with the pain lateral to the spine. Over 99% of back pain instances fall within this category.[4] The full differential diagnosis includes many other less common conditions.

- Mechanical:

- Apophyseal osteoarthritis

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Degenerative discs

- Scheuermann's kyphosis

- Spinal disc herniation ("slipped disc")

- Thoracic or lumbar spinal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis and other congenital abnormalities

- Fractures

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

- Unequal leg length

- Restricted hip motion

- Misaligned pelvis - pelvic obliquity, anteversion or retroversion Template:Nb10

- Abnormal foot pronation

- Inflammatory:

- Seronegative spondylarthritides (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Infection - epidural abscess or osteomyelitis

- Sacroiliitis

- Neoplastic:

- Bone tumors (primary or metastatic)

- Intradural spinal tumors

- Metabolic:

- Osteoporotic fractures

- Osteomalacia

- Ochronosis

- Chondrocalcinosis

- Psychosomatic

- Paget's disease

- Referred pain:

- Pelvic/abdominal disease

- Prostate Cancer

- Posture

- Oxygen deprivation

Pathophysiology

Sensation

In general, pain is an unpleasant feeling in response to stimuli that have the potential to damage or do damage the body's tissues (noxious stimuli). There are four fundamental steps in the process of pain perception: transduction, transmission, perception and modulation. The process starts when the potentially pain-causing event stimulates the endings of specialized nerve cells (nociceptors). A nociceptor converts the stimulus into an electrical signal by transduction. Several different types of nerve fibers carry out the transmission of the electrical signal from the transducing nociceptor to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, from there to the brain stem, and then from the brain stem to the various parts of the brain such as the thalamus and the limbic system. There, the pain signals are processed and given context in the process of pain perception. Through modulation, the brain can then modify the sending of further nerve impulses by signaling the release of neurotransmitters that either inhibit them (for example, serotonin and endorphins) or stimulate them.[5]

Afferent nerve fibers carry nerve impulses from sensory nerve cells in the lower back towards the central nervous system.[6] Signals travel to the dorsal root ganglia (the connections between the peripheral nerves and the central spinal nerves) along three types of afferent nerve fibers: A beta fibers, A delta fibers, and C fibers.[5] The fibers of the A group are coated to differing degrees with myelin,[5] an electrical insulator that prevents signal loss and increases transmission speed.[7] The A beta fibers transmit light touch and not pain messages, and as they are heavily myelinated, they transfer their signals quickly. The A delta and C fibers handle pain messages, and as they are less myelinated, they transfer their signals more slowly.[5] These nerve cells release certain chemicals (peptides) in response to painful stimuli.[5]

The afferent nerves, carrying all types of sensation, terminate at the multi-layered dorsal horn of the spinal cord.[5] Generally, the different layers carry different types of sensation so that, for example, the layers carrying pain signals are separate from the layers carrying touch signals.[5] The signals then travel from the dorsal horn to the brain.[5] In the brain, the signals interact with the limbic system.[5]

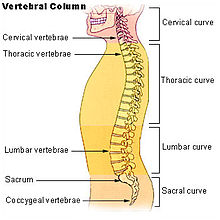

Back structures

The lumbar region (or lower back region) is made up of five vertebrae (L1-L5). In between these vertebrae lie fibrocartilage discs (intervertebral discs), which act as cushions, preventing the vertebrae from rubbing together while at the same time protecting the spinal cord. Nerves stem from the spinal cord through foramina within the vertebrae, providing muscles with sensations and motor associated messages. Stability of the spine is provided through ligaments and muscles of the back, lower back and abdomen. Small joints which prevent, as well as direct, motion of the spine are called facet joints (zygapophysial joints).[8]

Causes of lower back pain are varied. Most cases are believed to be due to a sprain or strain in the muscles and soft tissues of the back.[1] Overactivity of the muscles of the back can lead to an injured or torn ligament in the back which in turn leads to pain. An injury can also occur to one of the intervertebral discs (disc tear, disc herniation). Due to aging, discs begin to diminish and shrink in size, resulting in vertebrae and facet joints rubbing against one another. Ligament and joint functionality also diminishes as one ages, leading to spondylolisthesis, which causes the vertebrae to move much more than they should. Pain is also generated through lumbar spinal stenosis, sciatica and scoliosis. At the lowest end of the spine, some patients may have tailbone pain (also called coccyx pain or coccydynia). Others may have pain from their sacroiliac joint, where the spinal column attaches to the pelvis, called sacroiliac joint dysfunction which may be responsible for 22.6% of low back pain.[9] Physical causes may include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, degeneration of the discs between the vertebrae or a spinal disc herniation, a vertebral fracture (such as from osteoporosis), or rarely, an infection or tumor.[10]

In the vast majority of cases, no noteworthy or serious cause is ever identified. If the pain resolves after a few weeks, intensive testing is not indicated.[11][unreliable source]

Diagnostic approach

| Red flags[12] |

|---|

| Recent significant trauma |

| Milder trauma if age > 50 |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| Unexplained fever |

| Immunosuppression |

| History of cancer |

| Intravenous drug use |

| Osteoporosis |

| Chronic corticosteroid use |

| Age > 70 years |

| Focal neurological deficit |

| Duration > 6 weeks |

Differential diagnosis

For correct diagnosis, non-specific low back pain must be differentiated from radiculopathy and serious spinal problems such as a tumor, infection or spinal fracture. Certain signs, termed "red flags," may indicate a more serious condition, and prompt a more extensive investigation using diagnostic imaging or laboratory testing; even so, most individuals seeking treatment for acute low back pain have one or more red flags but no serious underlying problem.[2][3] In addition, the successful finding of some red flags comes with a high risk of a false-positive diagnosis of spinal malignancy or vertebral fracture, and evidence does not clearly support their use for making such diagnoses, especially ones based on the presence of only one red flag.[13][14] With other causes ruled out, people with non-specific low back pain typically are treated symptomatically, without exact determination of the underlying cause.[2][3]

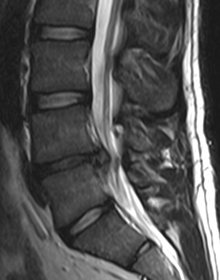

Imaging

Complaints of lower back pain are one of the most common reasons why people visit doctors.[15] Although medical societies do not recommend imaging tests such as an X-ray, CT scan, or MRI within a few weeks of the onset of pain as the pain is likely to subside,[15] many patients and doctors use them to try to find the cause of the pain.[15] Such tests are not required in lower back pain except in the cases where "red flags" are present,[16][17] and fewer than 1% of imaging tests identify the cause of a problem.[15] In most cases, the tests are not necessary, and most people with feel better after a month regardless of whether they undergo imaging.[15] Routine imaging may be harmful to a person's health from the radiation used, and more imaging is associated with higher expense and higher rates of surgery but no resultant benefit.[18] Imaging may also detect harmless abnormalities which encourage the patient to request further unnecessary testing or to worry.[15] Even so, from 1994 to 2006, in the United States, MRI scans of the lumbar region increased by more than 300% among Medicare beneficiaries.[19]

Prevention

Exercise is effective in preventing recurrence of non-acute pain; however, in the treatment of acute episodes results are mixed.[20] Proper lifting techniques may be useful.[21] Lumbar support does not appear effective.[22] Firm mattresses have demonstrated less effectiveness in preventing back pain than medium-firm mattresses.[23]

Cigarette smoking impacts the success and proper healing of spinal fusion surgery in patients who undergo cervical fusion; rates of nonunion are significantly greater for smokers than for nonsmokers.[24] Smoke and nicotine accelerate spine deterioration, reduce blood flow to the lower spine, and cause discs to degenerate.[25]

Management

For acute cases that are not debilitating, the treatment goal is to restore normal function and return the individual to work while minimizing pain. The condition is normally not serious, most often resolves without significant intervention, and recovery is aided by attempting to resume normal activity as soon as possible within the limits of pain; providing afflicted individuals with coping skills through reassurance of these facts is effective in hastening recovery.[3] Low back pain may be best treated with conservative self-care,[26] including: application of heat or cold,[27][28] and continued activity within the limits of the pain.[2] Engaging in physical activity within the limits of pain aids recovery. Prolonged bed rest (more than 2 days) is considered counterproductive.[29] Even with cases of severe pain, some activity is preferred to prolonged sitting or lying down - excluding movements that would further strain the back.[11][unreliable source] Structured exercise in acute low back pain has demonstrated neither improvement nor harm.[20] Heat application may have a modest benefit. The evidence for cold therapy however is limited.[27]

Low back pain is more likely to be persistent among people who previously required time off from work because of low back pain, those who expect passive treatments to help, those who believe that back pain is harmful or disabling or fear that any movement whatever will increase their pain, and people who have depression or anxiety.[11][unreliable source] A number of factors predict disability from back pain and include those who have poor coping behaviors or who fear activity are about 2.5 times as likely to have poor outcomes at a year.[30] Intensive multidisciplinary treatment programs may help subacute[29] or chronic[31] low back pain.[11][unreliable source] Behavioral therapy may be useful.[31]

Physical therapy

Physical therapy can include heat, ice, massage, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation. Active therapies can consist of stretching, strengthening and aerobic exercises. Exercising to restore motion and strength to the lower back can be very helpful in relieving pain and preventing future episodes of low back pain.[32] Treatment according to McKenzie method is somewhat effective for acute low back pain, but not for chronic low-back pain.[33] The benefit in the short term does not appear clinically significant.[3] Exercise therapy appears to be slightly effective at reducing pain and improving function in the treatment of chronic low back pain.[34] Compared to usual care, exercise therapy improved post-treatment pain intensity and disability, and long-term function.[35] Exercise programmes are effective for chronic LBP up to 6 months after treatment cessation, evidenced by pain score reduction and reoccurrence rates.[36] There is no evidence that one particular type of exercise therapy is clearly more effective than others.[37] The Alexander technique appears useful for chronic back pain.[38] There is tentative evidence to support the use of yoga.[39]

Medications

Short term use of pain and anti-inflammatory medications, such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen may help relieve the symptoms of lower back pain.[29][31] NSAIDs are slightly effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low-back pain without sciatica.[40] Muscle relaxants for acute and chronic pain have some benefit,[29][31] and are more effective in relieving pain and spasms when used in combination with NSAIDs.[41] Oral steroids have not been shown to be useful.[3]

Antidepressants appear ineffective in the treatment of chronic back pain[42] even though some previous studies found them helpful.[31] Tricyclic antidepressants are recommended in a 2007 guideline by the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society.[43] Prolotherapy, facet joint injections, and intradiscal steroid injections have not been found to be effective.[44] Epidural corticosteroid injections provide only slight temporary relief of sciatica with no long term benefit.[45] The role of narcotics for chronic low back pain is uncertain.[46]

Manual therapies

It is not known if chiropractic care improves clinical outcomes in those with lower back pain more or less than other treatments.[47] A 2012 Cochrane review found that spinal manipulation was no more effective than either inert interventions, sham manipulation, or other treatments and adding it to other treatment does not appear to increase the benefit.[48] A 2010 systematic review found that most studies suggest SM achieves equal or superior improvement in pain and function when compared with other commonly used interventions for short, intermediate, and long-term follow-up.[49] National guidelines come to different conclusions with some not recommending spinal manipulation, some describing manipulation as optional, and others recommending a short course in those who do not improve with other treatments.[2] The American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society recommend that it be considered for people who do not improve with self care options.[26] Acupuncture and massage is without substantial benefit.[3]

The effectiveness of spinal manipulation is more or less equal to other commonly prescribed treatment for chronic low-back pain, such as, exercise therapy, standard medical care or physiotherapy.[50] Some national guidelines consider its use optional, some do not recommend and others suggest a short course in those who do not improve with other measures.[2] Manipulation under anaesthesia, or medically assisted manipulation, currently has insufficient evidence to make any strong recommendations.[51] Acupuncture may help chronic pain;[31] however, a more recent randomized controlled trialsuggested insignificant difference between real and sham acupuncture.[52] Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has not been found to be effective in chronic lower back pain.[53] Massage therapy may benefit some to those with prolonged pain.[54]

Surgery

Surgery may be indicated when conservative treatment is not effective or when a person develops progressive and functionally limiting neurological symptoms such as leg weakness, bladder or bowel incontinence.[55] Spinal fusion has been shown not to improve outcomes in those with simple chronic low back pain.[56] Discectomy, in those with a herniated disc causing nerve root compression, resulted in better outcomes at one year but not in four to ten years.[55] Benefits of spinal surgery are limited when dealing with degenerative discs.[57] Surgical implants increased the risk with no added improvement in pain or function.[19]

Prognosis

Determining a general prognosis from the available evidence for low back pain is difficult. Inconsistencies in the data are probably due to variations across the sources in the definitions used for the characteristics of the condition. As well, the studies lack of the ideal kinds of evidence about the condition.[58]

Acute

In general, the short term prognosis for acute low back pain is positive. Pain and disability usually improve significantly in the first six weeks after onset of symptoms. After six weeks, improvement slows with only small gains up to one year. At one year after onset, pain and disability levels are low to minimal, on average. One review found distress, previous low back pain incidents, and job satisfaction to be probable prognostic factors.[58]

Chronic

For persistent low back pain, the short term prognosis is also positive, with significant improvement in the first six weeks, but very little improvement after that. At one year, those with chronic low back pain can anticipate still having moderate pain and disability.[58] Poor pain coping skills, functional impairment, poor general health, and a significant psychological (Waddell's signs) or psychiatric component to the pain are probable prognostic factors for chronic pain.[30]

Epidemiology

Low back pain that lasts at least one day and limits activity is a very common and widespread complaint.[59] Over a lifetime, 80% of people have lower back pain,[42] with the difficulty most often beginning between 20 and 40 years old.[3] Globally, approximately 9 to 12% of people have lower back pain at any given point in time, and nearly one quarter (23.2%) report having it at some point over any given one-month period.[59][60]

It is most common among women, and among people aged 40–80 years, with the overall number of individuals affected expected to increase as the population ages. Women may be more prone to raise the complaint due to pain related to osteoporosis, menstruation or pregnancy, or it may be that women are more willing than men to report pain due to differences in social expectations between the two groups. Prevalence is elevated among adolescents, with females reporting it earlier than males, possibly showing a correlation between low back pain and the onset of puberty, as females enter puberty earlier than males.[59] Of American adults, 26% report pain of at least one day in duration every three months.[61]

History

Low back pain has been with humans since at least the Bronze Age. The oldest known surgical treatise - the Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to about 1500 BCE - describes a diagnostic test and treatment for a physician to use on encountering a vertebral sprain. Hippocrates (c. 460 BCE – c. 370 BCE) was the first to make use of terms for sciatic pain and low back pain; Galen (active mid to late second century CE) detailed the concepts. Physicians through the end of the first millennium did not attempt back surgery of any kind, and recommended only watchful waiting. Through the Medieval period, folk medicine practitioners provided treatments for back pain based on the belief that it was caused by spirits.[62]

By the start of the 20th century, physicians thought low back pain was simply caused by inflammation of or damage to the nerves,[62] with neuralgia and neuritis frequently cited;[63] the popularity of such proposed neural main etiologies declined steadily throughout the century.[63] In the 1920s and 30s, new theories for the cause of low pack pain arose, with physicians proposing a combination of nervous system and psychological disorders such as neurasthenia, hysteria, or psychogenesis.[62] Muscular causes such as "muscular rheumatism" (now called fibromyalgia) were cited with increasing frequency as well.[63]

Emerging technologies such as radiography gave physicians new diagnostic tools, which revealed the intervertebral disk as a source for back pain. In 1938, orthopedic surgeon Joseph S. Barr reported on cases of disk-related sciatica improved or cured with back surgery;[63] consequently, in the 1940s, the vertebral disk model of low back pain took over,[62] dominating the literature through the 1980s, especially after the rise of new imaging technologies such as CT and MRI.[63] Such discussion later subsided as further research showed that it was actually relatively uncommon for disk problems to be the source of the pain, but even with the knowledge that diagnostic tools could show abnormalities probably unrelated to the patient's pain, physicians would still look to the tools' results instead of physical examinations for diagnosis and treatment plans. Since then, physicians have come to question whether it is likely that they will be able to identify a specific cause for a complaint of low back pain, or whether finding one is even necessary, as most complaints resolve themselves within six to 12 week regardless of treatment.[62]

Economics

In the United States, estimates of the costs of low back pain range between $38 and $50 billion a year and there are 300,000 operations annually. Back and neck operations are the third most common form of surgery in the United States.[64] Between 1990 and 2001 there was a 220% increase in spinal fussions in the United States, despite the fact that during that period there were no changes, clarifications, or improvements in the indications for surgery or new evidence of improved effectiveness.[19]

Women

Women may experience acute low back pain due to certain medical conditions of the female reproductive system, including endometriosis, ovarian cysts, ovarian cancer, or uterine fibroids.[65]

An estimated 50-70% of pregnant women experience back pain.[66] As one gets farther along in the pregnancy, due to the additional weight of the fetus, one’s center of gravity will shift forward causing one’s posture to change. This change in posture leads to increasing lower back pain.[66][67]

References

- ^ a b c "Lower Back Pain Fact Sheet. nih.gov". Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ^ a b c d e f Koes, BW (2010 Dec). "An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care". European Spine Journal. 19 (12): 2075–94. PMID 20602122.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Casazza, BA (2012 Feb 15). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute low back pain". American family physician. 85 (4): 343–50. PMID 22335313.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM; et al. (2009). "Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain". Arthritis Rheum. 60 (10): 3072–80. doi:10.1002/art.24853. PMID 19790051.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Salzberg L (2012). "The physiology of low back pain". Prim. Care. 39 (3): 487–98. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.014. PMID 22958558.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Physiology of Behavior (11 ed.). 2012. ISBN 978-0205239399.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Hartline DK (2008). "What is myelin?". Neuron Glia Biol. 4 (2): 153–63. doi:10.1017/S1740925X09990263. PMID 19737435.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Floyd, R., & Thompson, Clem. (2008). Manual of structural kinesiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

- ^ T N Bernard and W H Kirkaldy-Willis, "Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain," Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, no. 217 (April 1987) 266-280.

- ^ Burke,G.L.,MD, (1964). Backache: From Occiput to Coccyx. Vancouver, BC: Macdonald Publishing.

- ^ a b c d Atlas SJ (2010). "Nonpharmacological treatment for low back pain". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (1): 20–27.[unreliable source]

- ^ "American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria - Low Back Pain" (PDF). American College of Radiology.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Henschke N, Maher CG, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L (2013). "Red flags to screen for malignancy in patients with low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD008686. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008686.pub2. PMID 23450586.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams CM, Henschke N, Maher CG; et al. (2013). "Red flags to screen for vertebral fracture in patients presenting with low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD008643. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008643.pub2. PMID 23440831.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Use of imaging studies for low back pain: percentage of members with a primary diagnosis of low back pain who did not have an imaging study (plain x-ray, MRI, CT scan) within 28 days of the diagnosis". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-06Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Chou, R (2009 Feb 7). "Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9662): 463–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0. PMID 19200918.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Crownover BK, Bepko JL (2013). "Appropriate and safe use of diagnostic imaging". Am Fam Physician. 87 (7): 494–501. PMID 23547591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chou, R (2011 Feb 1). "Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians". Annals of internal medicine. 154 (3): 181–9. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00008. PMID 21282698.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Deyo, RA; Mirza, SK; Turner, JA; Martin, BI (2009). "Overtreating Chronic Back Pain: Time to Back Off?". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 22 (1): 62–8. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.080102. PMC 2729142. PMID 19124635.

- ^ a b Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, Jiang JY (2010). Choi, Brian KL (ed.). "Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD006555. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006555.pub2. PMID 20091596.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Delavier, Frédéric. Strength training anatomy. Human Kinetics Publishers, 2006. Print.

- ^ van Duijvenbode, IC (2008 Apr 16). "Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD001823. PMID 18425875.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kovacs FM, Abraira V, Peña A; et al. (2003). "Effect of firmness of mattress on chronic non-specific low-back pain: randomised, double-blind, controlled, multicentre trial". The Lancet. 362 (9396): 1599–604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14792-7. PMID 14630439.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.spineuniverse.com/wellness/cigarette-smoking-its-impact-spinal-fusions

- ^ Mayo Clinic (2008). Back pain guide [on-line].

- ^ a b Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V; et al. (October 2, 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Ann Intern Med. 147 (7): 478–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. PMID 17909209.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b French, Simon D; Cameron, Melainie; Walker, Bruce F; Reggars, John W; Esterman, Adrian J; French, Simon D (2006). French, Simon D (ed.). "Superficial heat or cold for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD004750. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004750.pub2. PMID 16437495.

- ^ "Heat or Cold Packs for Neck and Back Strain: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Efficacy. Gregory Garra. 2010; Academic Emergency Medicine - Wiley InterScience".

- ^ a b c d Koes B, van Tulder M (2006). "Low back pain (acute)". Clinical evidence (15): 1619–33. PMID 16973062.

- ^ a b Chou, R; Shekelle, P (2010). "Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain?". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (13): 1295–302. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.344. PMID 20371789.

- ^ a b c d e f van Tulder M, Koes B (2006). "Low back pain (chronic)". Clinical evidence (15): 1634–53. PMID 16973063.

- ^ http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00311

- ^ MacHado, LA; De Souza, MS; Ferreira, PH; Ferreira, ML (2006). "The McKenzie method for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis approach". Spine. 31 (9): E254–62. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000214884.18502.93. PMID 16641766.

- ^ Hayden, Jill; Van Tulder, Maurits W; Malmivaara, Antti; Koes, Bart W; Hayden, Jill (2005). Hayden, Jill (ed.). "Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD000335. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2. PMID 16034851.

- ^ van van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, Verhagen AP, Ostelo R, Koes BW, van Tulder MW (2011). "A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain". Eur Spine J. 20 (1): 19–39. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3. PMC 3036018. PMID 20640863.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith C, Grimmer-Somers K. (2010). "The treatment effect of exercise programmes for chronic low back pain". J Eval Clin Pract. 16 (3): 484–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01174.x. PMID 20438611.

- ^ van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Koes BW, van Tulder MW (2010). "Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 24 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002. PMID 20227641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woodman, JP (2012 Jan). "Evidence for the effectiveness of Alexander Technique lessons in medical and health-related conditions: a systematic review". International journal of clinical practice. 66 (1): 98–112. PMID 22171910.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Posadzki, P (2011 Sep). "Yoga for low back pain: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Clinical rheumatology. 30 (9): 1257–62. PMID 21590293.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Roelofs PDDM, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJPM, van Tulder MW (2008). Roelofs, Pepijn DDM (ed.). "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3. PMID 18253976.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Malanga GA, Dunn KR. Low back pain management: approaches to treatment. J Musculoskel Med. 2010;27:305-315.

- ^ a b Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WW, Roland M, van Tulder MW (2008). Urquhart, Donna M (ed.). "Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001703.pub3. PMID 18253994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ King SA (July 1, 2008). "Update on Treatment of Low Back Pain: Part 2". Psychiatric Times. 25 (8).

- ^ Chou, Roger; Loeser, John D.; Owens, Douglas K.; Rosenquist, Richard W.; Atlas, Steven J.; Baisden, Jamie; Carragee, Eugene J.; Grabois, Martin; Murphy, Donald R. (2009). "Interventional Therapies, Surgery, and Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation for Low Back Pain". Spine. 34 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a1390d. PMID 19363457.

- ^ Pinto, RZ (2012 Dec 18). "Epidural corticosteroid injections in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of internal medicine. 157 (12): 865–77. PMID 23362516.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Deshpande A, Furlan A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk D (2007). Deshpande, Amol (ed.). "Opioids for chronic low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004959. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub3. PMID 17636781.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walker, BF (2011 Feb 1). "A Cochrane review of combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain". Spine. 36 (3): 230–42. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318202ac73. PMID 21248591.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rubinstein, SM (2012 Sep 12). "Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 9: CD008880. PMID 22972127.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dagenais, S; Gay, RE; Tricco, AC; Freeman, MD; Mayer, JM (2010). "NASS Contemporary Concepts in Spine Care: spinal manipulation therapy for acute low back pain". The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 10 (10): 918–40. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2010.07.389. PMID 20869008.

- ^ Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJ, de Boer MR, van Tulder MW (2011). Rubinstein, Sidney M (ed.). "Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD008112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008112.pub2. PMID 21328304.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dagenais, S; Mayer, J; Wooley, J; Haldeman, S (2008). "Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with medicine-assisted manipulation". The Spine Journal. 8 (1): 142–9. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2007.09.010. PMID 18164462.

- ^ Haake M, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C; et al. (2007). "German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized, Multicenter, Blinded, Parallel-Group Trial With 3 Groups". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (17): 1892–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. PMID 17893311.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dubinsky, R. M.; Miyasaki, J. (2009). "Assessment: Efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain in neurologic disorders (an evidence-based review): Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 74 (2): 173–6. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c918fc. PMID 20042705.

- ^ Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T, Irvin E (2008). "Massage for low-back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). PMID 18843627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Manusov, EG (2012 Sep). "Surgical treatment of low back pain". Primary care. 39 (3): 525–31. PMID 22958562.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "BestBets: Spinal fusion in chronic back pain".

- ^ Mirza, SK; Deyo, RA (2007). "Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain". Spine. 32 (7): 816–23. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000259225.37454.38. PMID 17414918.

- ^ a b c Menezes Costa Lda, C (2012 Aug 7). "The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 184 (11): E613-24. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111271. PMC 3414626. PMID 22586331.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing pipe in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G; et al. (2012). "A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain". Arthritis Rheum. 64 (6): 2028–37. doi:10.1002/art.34347. PMID 22231424.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vos, T (2012 Dec 15). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. PMID 23245607.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Deyo, Richard A.; Mirza, Sohail K.; Martin, Brook I. (2006). "Back Pain Prevalence and Visit Rates". Spine. 31 (23): 2724–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. PMID 17077742.

- ^ a b c d e Maharty DC (2012). "The history of lower back pain: a look "back" through the centuries". Prim. Care. 39 (3): 463–70. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2012.06.002. PMID 22958555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Lutz GK, Butzlaff M, Schultz-Venrath U (2003). "Looking back on back pain: trial and error of diagnoses in the 20th century". Spine. 28 (16): 1899–905. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000083365.41261.CF. PMID 12923482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ACSM's Resources for Clinical Exercise Physiology: Musculoskeletal, Neuromuscular, Neoplastic, Immunologic and Hematologic Conditions (2 ed.). 2009. p. 149. ISBN 978-0781768702.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Low back pain - acute". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b Danforth Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, 2003, James. Gibbs, et al, Ch. 1

- ^ Williams Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, 2005, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 8,