Genetic genealogy: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m [432]Add: title, year, last1, first1, journal, volume, issue, pages. Tweak: title, journal, volume, issue. | RebekahThorn |

RebekahThorn (talk | contribs) →Additional readings: Adding some journal articles that mention genetic genealogy |

||

| Line 158: | Line 158: | ||

*{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.01.012|title=The impact of additional Y-STR loci on resolving common haplotypes and closely related individuals|year=2007|last1=Decker|first1=A.E.|last2=Kline|first2=M.C.|last3=Vallone|first3=P.M.|last4=Butler|first4=J.M.|journal=Forensic Science International: Genetics|volume=1|issue=2|pages=215}} |

*{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.01.012|title=The impact of additional Y-STR loci on resolving common haplotypes and closely related individuals|year=2007|last1=Decker|first1=A.E.|last2=Kline|first2=M.C.|last3=Vallone|first3=P.M.|last4=Butler|first4=J.M.|journal=Forensic Science International: Genetics|volume=1|issue=2|pages=215}} |

||

*{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/ajpa.22233|title=Genetic genealogy comes of age: Perspectives on the use of deep-rooted pedigrees in human population genetics|year=2013|last1=Larmuseau|first1=M.H.D.|last2=Van Geystelen|first2=A.|last3=Van Oven|first3=M.|last4=Decorte|first4=R.|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=150|issue=4|pages=505–11|pmid=23440589}} |

*{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/ajpa.22233|title=Genetic genealogy comes of age: Perspectives on the use of deep-rooted pedigrees in human population genetics|year=2013|last1=Larmuseau|first1=M.H.D.|last2=Van Geystelen|first2=A.|last3=Van Oven|first3=M.|last4=Decorte|first4=R.|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=150|issue=4|pages=505–11|pmid=23440589}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{cite journal|doi=}} |

*{{cite journal|doi=}} |

||

--> |

--> |

||

Revision as of 02:39, 2 July 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Genetic genealogy |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

Genetic genealogy is the application of genetics to traditional genealogy. Genetic genealogy involves the use of genealogical DNA testing to determine the level of genetic relationship between individuals. It can be said that genetic genealogy has ridden the wave of popular genealogy and family history. Propelled further by public participation in the initial genographic project, hundreds of thousands of people have now tested seeking genealogical information or simply knowledge of their genetic heritage.

History

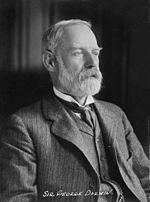

The investigation of surnames in genetics can be said to go back to George Darwin, a son of Charles Darwin. In 1875, George Darwin used surnames to estimate the frequency of first-cousin marriages and calculated the expected incidence of marriage between people of the same surname (isonymy). He arrived at a figure between 2.25% and 4.5% for cousin-marriage in the population of Great Britain, with the upper classes being on the high end and the general rural population on the low end.[1]

Population genetics and surname studies

It was over 100 years later that population geneticists began to use Y-Chromosome markers to provide evidence of common ancestry between individuals with a tradition of common ancestry. Two notable studies showed common heritage between men from Cohen Jewish lineages[2] and then common ancestry between descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s paternal line and male lineage descendants of the freed slave, Sally Hemmings.[3]

Bryan Sykes, a molecular biologist at Oxford University tested the new methodology in general surname research. His study of the Sykes surname obtained results by looking at four STR markers on the male chromosome. It pointed the way to genetics becoming a valuable assistant in the service of genealogy and history.[4]

Direct to consumer paternity testing

The first company to provide direct-to-consumer genetic DNA testing was the now defunct GeneTree. However, it did not at the time offer multi-generational genealogy tests. In fall 2001, GeneTree sold its assets to Salt Lake City-based Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation (SMGF) which originated in 1999.[5] While in operation, SMGF would provide free Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA tests to thousands.[6] Later, GeneTree would return to genetic testing for genealogy in conjunction with the Sorenson parent company and would eventually be part of the assets aquired in the Ancestry.com buyout of SMGF.[7]

The genetic genealogy revolution

In 2000, Family Tree DNA, founded by Bennett Greenspan and Max Blankfeld, was the first company dedicated to direct-to-consumer testing for genealogy research. They initially offered eleven marker Y-Chromosome STR tests and HVR1 mitochondrial DNA tests. They originally tested in partnership with the University of Arizona.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

The publication of Sykes The Seven Daughters of Eve in 2001, which described the seven major haplogroups of European ancestors, helped push personal ancestry testing through DNA tests into wide public notice. With the growing availability and affordability of genealogical DNA testing, genetic genealogy as a field grew rapidly. By 2003, the field of DNA testing of surnames was declared officially to have “arrived” in an article by Jobling and Tyler-Smith in Nature Reviews Genetics.[15] The number of firms offering tests, and the number of consumers ordering them, had risen dramatically.[16]

The Genographic project

The original Genographic Project was a five-year research study launched in 2005 by the National Geographic Society and IBM, in partnership with the University of Arizona and Family Tree DNA. Its goals are primarily anthropological, not genealogical. The project says that by April 2010 it had sold more than 350,000 of its public participation testing kits, which test the general public for either twelve STR markers on the Y-Chromosome or mutations on the HVR1 region of the mtDNA.[17]

In 2007, annual sales of genetic genealogical tests for all companies, including the laboratories that support them, are estimated to be in the area of $60 million (2006).[6]

Autosomal testing

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2013) |

Typical customers and interest groups

Male DNA testing customers most often start with a Y-Chromosome test to determine their father's paternal ancestry. Females generally begin with a mitochondrial test to trace their ancient maternal lineage, which males often have tested for the same purpose.

A common consumer goal in purchasing DNA testing services is to acquire quantified, scientific linkage to a specific ancestral group. A compelling example of this motive is found in the expressed desires of some consumers to be proven to have Viking paternal ancestry. In keeping with this marketplace demand, one British DNA testing service, Oxford Ancestors, offers a Y-Chromosome test purporting to assess whether given males are of "Viking stock." Those whose DNA falls into the designated haplogroup are issued Viking Descendant certificates by the testing service. The same DNA testing company participated in producing a televised documentary, "The Blood of the Vikings," in conjunction with the BBC, which showed how DNA testing could reveal Viking ancestry.

The RootsWeb Genealogy-DNA[18] Internet discussion group has a membership of 750 subscribers from around the world. Some subscribers have had various DNA tests performed and are seeking advice and guidance in interpreting their results. The list also includes administrators of DNA projects that examine surnames, geographic regions, or ethnic groups. The sophistication of subscribers ranges from expert to novice. In some cases, subscribers have been credited with making useful and novel contributions to knowledge in the field of genetic genealogy.[citation needed]

Citizen Science and ISOGG

One of the earliest groups the to emerge in genetic genealogy was the International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG). Their stated goal is to promote DNA testing for genealogy.[19] Members advocate the use of genetics in genealogical research and the group facilitates networking among self-styled genetic genealogists.[20]

The ISOGG Y-chromosome tree

Beginning in 2006, ISOGG began to create and maintain the ISOGG Y-haplogroup tree,[21][20] From 2006 through mid-2013, each page carried the note,

ISOGG (International Society of Genetic Genealogy) is not affiliated with any registered, trademarked, and/or copyrighted names of companies, websites and organizations. The Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2006 is for informational purposes only, and does not represent an endorsement by ISOGG.

[21] The tree has a set goal of being the most current possible tree. This is possible partly because it uses both "consenting research subjects and individuals pursuing genetic genealogy."[22] Yet more recently the tree has been described as providing the "accepted nomenclature" for human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups and subclades.[23]

Uses

Mitochondrial DNA and direct maternal lineages

mtDNA testing involves sequencing or testing the parts of the hypervariable region (HVR1 or HVR2) or the complete mitochondrial genome (mtGenome). An mtDNA test that only tests part of the hypervariable region may also include the additional SNPs needed to assign people to a maternal haplogroup.[24]

Direct paternal lineages

Y-Chromosome DNA (Y-DNA) testing involves short tandem repeat (STR) and, sometimes, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) testing of the Y-Chromosome. The Y-Chromosome is present only in males and reveals information strictly on the paternal line. These tests can provide insight into the recent (via STRs) and ancient (via SNPs) genetic ancestry. A Y-chromosome STR test will reveal a haplotype, which should be similar among all male descendants of a male ancestor. SNP tests are used to assign people to a paternal haplogroup, which defines a much larger genetic population.[25][26]

Biogeographical and ethnic origins

Additional DNA tests exist for determining biogeographical and ethnic origin, but these tests have less relevance for traditional genealogy.

Genetic genealogy has revealed astonishing links between peoples. For instance, it has shown that the ancient Phoenician people were ancestors of much of the present-day population of the island of Malta. Preliminary results from a study by Pierre Zalloua of the American University of Beirut and Spencer Wells, supported by a grant from National Geographic's Committee for Research and Exploration, were published in the October 2004 issue of National Geographic. One of the conclusions is that "more than half of the Y-Chromosome lineages that we see in today's Maltese population could have come in with the Phoenicians."[27]

Human migration

Genealogical DNA testing methods are also being used on a longer time scale to trace human migratory patterns. For example, they have been used to determine when the first humans came to North America and what path they followed.

For several years, a number of researchers and laboratories from around the world have been sampling indigenous populations from around the globe in an effort to map historical human migration patterns. Recently, several projects have been created that are aimed at bringing this science to the public. One example, mentioned in History above, is the National Geographic Society's Genographic Project, which aims to map historical human migration patterns by collecting and analyzing DNA samples from over 100,000 people across five continents. Another example is the DNA Clans Genetic Ancestry Analysis, which measures a person's precise genetic connections to indigenous ethnic groups from around the world.[28]

See also

- Allele

- Allele frequency

- Electropherogram

- Family name

- Genealogical DNA test

- Genealogy

- Genetic recombination

- Haplogroup

- Haplotype

- Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups

- Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups

- Human mitochondrial genetics

- Human genetic clustering

- Most recent common ancestor

- Short tandem repeat (STR)

- Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

- Y-STR (Y-chromosome short tandem repeat)

- Y-chromosome haplogroups by populations

- Non-paternity event

References

- ^ Darwin, George H. (Sep., 1875). "Note on the Marriages of First Cousins". Journal of the Statistical Society of London. 38 (3): 344–348. doi:10.2307/2338771.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Skorecki, Karl; Selig, Sara; Blazer, Shraga; Bradman, Robert; Bradman, Neil; Waburton, P. J.; Ismajlowicz, Monica; Hammer, Michael F. (1 January 1997). "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests". Nature. 385 (6611): 32. doi:10.1038/385032a0. PMID 8985243.

- ^ Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty, 27 January 2012 – 14 October 2012, Smithsonian Institution, accessed 23 March 2012. Quote: "The [DNA test results show a genetic link between the Jefferson and Hemings descendants: A man with the Jefferson Y chromosome fathered Eston Hemings (born 1808). While there were other adult males with the Jefferson Y chromosome living in Virginia at that time, most historians now believe that the documentary and genetic evidence, considered together, strongly support the conclusion that [Thomas] Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings's children."

- ^ Sykes, Bryan; Irven, Catherine (2000). "Surnames and the Y Chromosome". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (4): 1417. doi:10.1086/302850.

- ^ ""CMMG alum launches multi-million dollar genetic testing company - Alum notes" (PDF). 17 (2). Wayne State University, School of Medicine's alumni journal. Spring 2006: 1. Retrieved 24 Jan 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "How Big Is the Genetic Genealogy Market?". The Genetic Genealogist. Retrieved 19 Feb 2009.

- ^ "Ancestry.com Launches new AncestryDNA Service: The Next Generation of DNA Science Poised to Enrich Family History Research" (Press release). Retrieved 1 July 2013.

{{cite press release}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ Belli, Anne (January 18, 2005). "Moneymakers: Bennett Greenspan". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

Years of researching his family tree through records and documents revealed roots in Argentina, but he ran out of leads looking for his maternal great-grandfather. After hearing about new genetic testing at the University of Arizona, he persuaded a scientist there to test DNA samples from a known cousin in California and a suspected distant cousin in Buenos Aires. It was a match. But the real find was the idea for Family Tree DNA, which the former film salesman launched in early 2000 to provide the same kind of service for others searching for their ancestors.

- ^ "National Genealogical Society Quarterly". 93 (1–4). National Genealogical Society. 2005: 248.

Businessman Bennett Greenspan hoped that the approach used in the Jefferson and Cohen research would help family historians. After reaching a brick wall on his mother's surname, Nitz, he discovered and Argentine researching the same surname. Greenspan enlisted the help of a male Nitz cousin. A scientist involved in the original Cohen investigation tested the Argentine's and Greenspan's cousin's Y chromosomes. Their haplotypes matched perfectly.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lomax, John Nova (April 14, 2005). "Who's Your Daddy?". Houston Press. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

A real estate developer and entrepreneur, Greenspan has been interested in genealogy since his preteen days.

- ^ Capper, Russ (November 15, 2008). "Bennett Greenspan of FamilyTreeDNA.com". The BusinessMakers Radio Show. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Dardashti, Schelly Talalay (March 30, 2008). "When oral history meets genetics". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

Greenspan, born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, has been interested in genealogy from a very young age; he drew his first family tree at age 11.

- ^ Gibbens, Pam (April 2006). "Talk of The Town – At Familytree DNA, it's all Relative". Greater Houston Weekly / Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ Bradford, Nicole (24 Feb 2008). "Riding the 'genetic revolution'". Houston Business Journal. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Jobling, Mark A.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2003). "The human Y chromosome: An evolutionary marker comes of age". Nature Reviews Genetics. 4 (8): 598–612. doi:10.1038/nrg1124. PMID 12897772.

- ^ Deboeck, Guido. "Genetic Genealogy Becomes Mainstream". BellaOnline. Retrieved 19 Feb 2009.

- ^ "The Genographic Project: A Landmark Study of the Human Journey". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 Feb 2009.

- ^ "Rootsweb Genealogy-DNA Mailing List". Rootsweb (by Ancestry.com).

- ^ "The International Society of Genetic Genealogy". Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ a b King, TE (2009). "What's in a name? Y chromosomes, surnames and the genetic genealogy revolution". Trends in Genetics. 25 (8): 351–360. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2009.06.003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b International Society of Genetic Genealogy (2006)). "Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2006, Version: 1.24, Date: 7 June 2007". Retrieved 1 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Gitschier, Jane (2009). "Inferential Genotyping of Y Chromosomes in Latter-Day Saints Founders and Comparison to Utah Samples in the HapMap Project". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (2): 251. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.018.

- ^ van Holst Pellekaan, Sheila (2013). "Genetic evidence for the colonization of Australia". Quaternary International. 285: 44–56. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.04.014.

- ^ Family Tree DNA Editorial Team (2013). "Understanding Results: mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA)". Gene by Gene. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Family Tree DNA Editorial Team (2013). "Understanding Results: Y-DNA Short Tandem Repeat (STR)". Gene by Gene. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Family Tree DNA Editorial Team (2013). "Understanding Results: Y-DNA Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)". Gene by Gene. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Franklin-Barbajosa, Cassandra (Oct 2004). "In the Wake of the Phoenicians: DNA study reveals a Phoenician-Maltese link". National Geographic Online. Retrieved 19 Feb 2009.

- ^ "DNA Clans (Y-Clan) - DNA Ancestry Analysis". Genebase. Retrieved 19 Feb 2009.

Additional readings

Books

- Terrence Carmichael and Alexander Kuklin (2000). How to DNA Test Our Family Relationships. DNA Press. Early book on adoptions, paternity and other relationship testing. Carmichael is a founder of GeneTree.

- L. Cavalli-Sforza et al. (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Luigi-Luca and Francesco Cavalli-Sforza (1998). The Great Human Diasporas, translated from the Italian by Sarah Thorne. Reading, Mass. : Perseus Books.

- Colleen Fitzpatrick and Andrew Yeiser (2005). DNA and Genealogy. Rice Book Press.

- Clive Gamble (1993). Timewalkers: The Prehistory of Global Colonization. Stroud: Sutton.

- M. Jobling (2003). Human Evolutionary Genetics.

- Steve Olson (2002). Mapping Human History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Survey of major populations.

- Stephen Oppenheimer (2003). The Real Eve. Modern Man’s Journey out of Africa. Carroll & Graf.

- PBS (2003). The Journey of Man DVD. Broadcast aired in January 2003, Spencer Wells, host.

- Chris Pomery (2004) DNA and Family History: How Genetic Testing Can Advance Your Genealogical Research. London: National Archives. Early guide for do-it-yourself genealogists. Now updated (2007) as Family History in the Genes: Trace Your DNA and Grow Your Family Tree.

- Alan Savin (2003). DNA for Family Historians. Maidenhead: Genetic Genealogy Guides.

- Thomas H. Shawker (2004). Unlocking Your Genetic History: A Step-by-Step Guide to Discovering Your Family's Medical and Genetic Heritage (National Genealogical Society Guide, 6). Guide to the difficult subject of family medical history and genetic diseases.

- Megan Smolenyak and Ann Turner (2004). Trace Your Roots with DNA: Using Genetic Tests to Explore Your Family Tree. Rodale Books, ISBN 978-1-59486-006-5. Out of date but still worth reading.

- Bryan Sykes (2001) The Seven Daughters of Eve. The Science that Reveals Our Genetic Ancestry. New York, Norton. Names the founders of Europe’s major female haplogroups Helena, Jasmine, Katrine, Tara, Velda, Xenia, and Ursula.

- Bryan Sykes (2004). Adam's Curse. A Future without Men. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Linda Tagliaferro (1999). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Decoding Your Genes. Alpha Books.

- Spencer Wells (2004). The Journey of Man. New York: Random House.

Journals

- Wolinsky, Howard (2006). "Genetic genealogy goes global. Although useful in investigating ancestry, the application of genetics to traditional genealogy could be abused". EMBO reports. 7 (11): 1072–4. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400843. PMC 1679782. PMID 17077861.

- Nelson, A. (2008). "Bio Science: Genetic Genealogy Testing and the Pursuit of African Ancestry". Social Studies of Science. 38 (5): 759–83. doi:10.1177/0306312708091929. PMID 19227820.

- Williams, Sloan R. (2005). "Genetic Genealogy: The Woodson Family's Experience". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 29 (2): 225. doi:10.1007/s11013-005-7426-3.

- Gymrek, M.; McGuire, A. L.; Golan, D.; Halperin, E.; Erlich, Y. (2013). "Identifying Personal Genomes by Surname Inference". Science. 339 (6117): 321–4. doi:10.1126/science.1229566. PMID 23329047.

- El-Haj, Nadia ABU (2007). "Rethinking genetic genealogy: A response to Stephan Palmi�". American Ethnologist. 34 (2): 223. doi:10.1525/ae.2007.34.2.223.

{{cite journal}}: replacement character in|title=at position 58 (help) - Van Oven, Mannis; Kayser, Manfred (2009). "Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation". Human Mutation. 30 (2): E386–94. doi:10.1002/humu.20921. PMID 18853457.

- Sims, Lynn M.; Garvey, Dennis; Ballantyne, Jack (2009). Batzer, Mark A (ed.). "Improved Resolution Haplogroup G Phylogeny in the Y Chromosome, Revealed by a Set of Newly Characterized SNPs". PLoS ONE. 4 (6): e5792. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005792. PMC 2686153. PMID 19495413.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Tutton, Richard (2004). ""They want to know where they came from": Population genetics, identity, and family genealogy". New Genetics and Society. 23 (1): 105–20. doi:10.1080/1463677042000189606. PMID 15470787.

- Nash, Catherine (2004). "Genetic kinship". Cultural Studies. 18: 1. doi:10.1080/0950238042000181593.

- Royal, Charmaine D.; Novembre, John; Fullerton, Stephanie M.; Goldstein, David B.; Long, Jeffrey C.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Clark, Andrew G. (2010). "Inferring Genetic Ancestry: Opportunities, Challenges, and Implications". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (5): 661. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.011.

- Decker, A.E.; Kline, M.C.; Vallone, P.M.; Butler, J.M. (2007). "The impact of additional Y-STR loci on resolving common haplotypes and closely related individuals". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 1 (2): 215. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.01.012.

- Larmuseau, M.H.D.; Van Geystelen, A.; Van Oven, M.; Decorte, R. (2013). "Genetic genealogy comes of age: Perspectives on the use of deep-rooted pedigrees in human population genetics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 150 (4): 505–11. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22233. PMID 23440589.

- . doi:10.1046/j.1471-8731.2003.00069.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1007/s12687-011-0048-y.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1093/humrep/den052.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1177/0306312710379170.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1093/gbe/evt066.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . doi:10.1016/j.tig.2013.02.001.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links and resources

Maps

- National Geographic's interactive Atlas of the Human Journey

News

- MSNBC — Genetic Genealogy Front Page