Phalanx bone: Difference between revisions

→Structure: merge from Distal phalanges |

m →References: complete merge |

||

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

*[http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=4866 MedTerms.com Medical Dictionary] |

*[http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=4866 MedTerms.com Medical Dictionary] |

||

{{refbegin|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

* <!--Almécija-->{{cite doi|10.1371/journal.pone.0011727}} |

|||

* <!--Gough-Palmer-->{{cite doi|10.1148/rg.282075061 | date = March 2008}} |

|||

* <!--Hamrick-->{{cite pmid|9637179}} |

|||

* <!--Mittra-->{{cite pmid|17657781}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | ref = harv |

|||

| last1 = Shrewsbury | first1 = M |

|||

| last2 = Johnson | first2 = RK |

|||

| title = The Fascia of the Distal Phalanx |

|||

| journal = J Bone Joint Surg Am. | year = 1975 | issue = 57 | pages = 784–788 |

|||

| url = http://www.ejbjs.org/cgi/reprint/57/6/784.pdf |

|||

}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

{{Bones of skeleton}} |

{{Bones of skeleton}} |

||

Revision as of 08:39, 1 January 2014

It has been suggested that Distal phalanx be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2013. |

| Phalanx bone | |

|---|---|

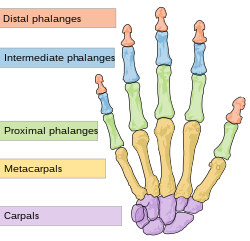

Illustration of the phalanges | |

The phalanges in a human hand | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Metacarpophalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, interphalangeal |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Phalanges |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The phalanges (singular: phalanx) are bones in the toes and fingers found in the limbs of most vertebrates. In humans and monkeys, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are long bones.

Structure

The phalanges are bones that exist on each finger and toe. There are 56 phalanges in the human body, with fourteen phalanges on each hand and foot. Three phalanges are present on each finger and toe, with the exception of the thumb and large toe, which possess only two. They are named according to whether they are proximal or distal, and according to the finger or toe they are in. The proximal phalanges are those that are closes to the hand or foot. These join with the metacarpals of the hand or metatarsals of the foot. The distal phalanges are the bones at the tips of the fingers or toes, and the middle phalanges are situated in between. The thumb and large toe do not possess a middle phalanx. [1]: 95

In the hand, the prominent, knobby ends of the proximal phalanx is often called the knuckle. The intermediate phalanx is not only intermediate in location, but is also usually intermediate in size among the other phalanges ("finger" bones).

The distal or terminal phalanges (singular phalanx) are the terminal limb bones located at the tip of the digits (i.e. fingers and toes). In human anatomy, the distal phalanges of the four fingers and toes articulate proximally with the intermediate phalanges at the distal interphalangeal joints (DIP); in the thumb and big toe, with only two phalanges, the distal phalanges articulate proximally with the proximal phalanges. The distal phalanges carry and shape nails and claws and are therefore occasionally referred to as the ungual phalanges. The distal phalanges are cone-shaped in most mammals, including most primates, but relatively wide and flat in humans.

Human anatomy

Fingers

The distal phalanges of the fingers are convex on their dorsal and flat on their volar surfaces; they are recognized by their small size, and by a roughened, elevated surface of a horseshoe form on the volar surface of the distal extremity of each which serves to support the sensitive pulp of the finger. [3]

In the distal phalanges of the hand the centres for the bodies appear at the distal extremities of the phalanges, instead of at the middle of the bodies, as in the other phalanges. Moreover, of all the bones of the hand, the distal phalanges are the first to ossify. [3]

In the hand, the distal ends of the distal phalanges possess flat and wide expansions called apical tufts. They serve to support the fleshy pad or pulp on the volar side of the fingertips and the nails on the dorsal side. [4]

The shaft of the distal phalanx is expanded proximally at the base and "waisted" distally. It ends in a crescent-shaped rough cap of bone epiphysis — the apical tuft (or ungual tuberosity/process) which covers a larger portion of the phalanx on the volar side than on the dorsal side. Two lateral ungual spines project proximally from the apical tuft. Near the base of the shaft are two lateral tubercles. Between these a V-shaped ridge extending proximally serves for the insertion of the flexor pollicis longus. Another ridge at the base serves for the insertion of the extensor aponeurosis. [5] The flexor insertion is sided by two fossae — the ungual fossa distally and the proximopalmar fossa proximally.

Thumb

The human pollical distal phalanx (PDP) has a pronounced insertion for the flexor pollicis longus (asymmetric towards the radial side), an ungual fossa, and a pair of dissymmetric ungual spines (the ulnar being more prominent). This asymmetry is necessary to ensure that the thumb pulp is always facing the pulps of the other digits, an osteological configuration which provides the maximum contact surface with held objects. [2]

Toes

The distal phalanges of the toes, in form, resemble those of the fingers; but they are smaller and are flattened from above downward; each presents a broad base for articulation with the corresponding bone of the second row, and an expanded distal extremity for the support of the nail and end of the toe. [6]

Location

Hand

The phalanges of the hand (Latin: Ossa digitorum manus, phalanges digitorum manus) are commonly known as the finger bones. They are fourteen in number, three for each finger, and two for the thumb on each hand. The names of the phalanges of the three rows of finger bones, from the hand out, are; proximal, intermediate and distal phalanges, while the thumb only contains a proximal and distal phalanx. Each consists of a body and two extremities.

- The body tapers from above downward, is convex posteriorly, concave in front from above downward, flat from side to side; its sides are marked by rough areas which give attachment to the fibrous sheaths of the flexor tendons.

- The proximal extremities of the bones of the first row present oval, concave articular surfaces, broader from side to side than from front to back. The proximal extremity of each of the bones of the second and third rows presents a double concavity separated by a median ridge.

- The distal extremities are smaller than the proximal, and each ends in two condyles (knuckles) separated by a shallow groove; the articular surface extends farther on the palmar than on the dorsal surface, a condition best marked in the bones of the first row.

The ungual phalanges, those most distal, are convex on their dorsal and flat on their volar surfaces; they are recognized by their small size, and by a roughened, elevated surface of a horseshoe form on the volar surface of the distal extremity of each which serves to support the sensitive pulp of the finger.

All of the five proximal phalanges articulate with a corresponding metacarpal bone in the hand through a metacarpophalangeal joint. The proximal, intermediate and distal phalanges articulates with one an other through interphalangeal articulations, proximal and distal interphalangeal joints respectively for the four fingers, while the thumb only contains one interphalangeal joint.

Foot

The phalanges are also present in the foot (Latin: ossa digitorum pedis, phalanges digitorum pedis). There are three phalanges for every toe, with the exception of the big toe, in which there are two. They differ from the phalanges of the hand in that, however, in their size, the bodies being much reduced in length, and, especially in the first row, laterally compressed.

- First row: The body of each is compressed from side to side, convex above, concave below. The base is concave; and the head presents a trochlear surface for articulation with the second phalanx.

- Second row: The phalanges of the second row are remarkably small and short, but rather broader than those of the first row.

The ungual phalanges, in form, resemble those of the fingers; but they are smaller and are flattened from above downward; each presents a broad base for articulation with the corresponding bone of the second row, and an expanded distal extremity for the support of the nail and end of the toe.

In the second, third, fourth, and fifth toes the phalanges of the first row articulate behind with the metatarsal bones, and in front with the second phalanges, which in their turn articulate with the first and third: the ungual phalanges articulate with the second.

-

Plan of ossification of the foot.

-

Bones of the left foot. Plantar surface.

-

Bones of foot

Development

The number of phalanges in animals is often expressed as a "phalangeal formula" that indicates the numbers of phalanges in digits, beginning from the innermost medial or proximal.

In animals

Most land mammals including humans have a 2-3-3-3-3 formula in both the hands (or paws) and feet. Primitive reptiles typically had the formula 2-3-4-4-5, and this pattern, with some modification, remained in many later reptiles and in the mammal-like reptiles. The phalangeal formula in the flippers of cetaceans (marine mammals) is 2-12-8-1.

In vertebrates, proximal phalanges have a similar placement in the corresponding limbs, be they paw, wing or fin. In many species, they are the longest and thickest phalanx ("finger" bone). The middle phalanx also a corresponding place in their limbs, whether they be paw, wing, hoof or fin.

-

Distal phalanges

-

-

-

-

Olduvai hominid

-

-

Interphalangeal ligaments and phalanges.Right hand. Deep dissection. Posterior (dorsal) view.

-

Interphalangeal ligaments and phalanges.Right hand. Deep dissection. Posterior (dorsal) view.

Primates

The morphology of the distal phalanges of human thumbs closely reflects an adaptation for a refined precision grip with pad-to-pad contact. While this has traditionally been associated with the advent of stone tool-making, the intrinsic hand proportions of australopiths and the resemblance between human hands and the short hands of Miocene apes, suggest that human hand proportions are largely plesiomorphic — in contrast to the derived elongated hand pattern and poorly developed thumb musculature of extant hominoids. The capability of a pad-to-pad precision grip in human hands is reflected in the morphology of the distal phalanges, especially in the pollical distal phalanges (PDP). [2]

In Neanderthals, the apical tufts were expanded and more robust than in modern and early upper Paleolithic humans. A proposal that Neanderthal distal phalanges was an adaptation to colder climate (than in Africa) is not supported by a recent comparison showing that in hominins, cold-adapted populations possessed smaller apical tufts than do warm-adapted populations. [7]

In non-human, living primates the apical tufts vary in size, but they are never larger than in humans. Enlarged apical tufts, to the extent they actually reflect expanded digital pulps, may have played a significant role in enhancing friction between the hand and held objects during Neolithic toolmaking. [4]

Among non-human primates phylogeny and style of locomotion appear to play a role in apical tuft size. Suspensory primates and New World monkeys have the smallest apical tufts, while terrestrial quadrupeds and Strepsirrhines have the largest. [7] A study of the fingertip morphology of four small-bodied New World monkey species, indicated a correlation between increasing small-branch foraging and reduced flexor and extensor tubercles in distal phalanges and broadened distal parts of distal phalanges. coupled with expanded apical pads and developed epidermal ridges. This suggests that widened distal phalanges were developed in arboreal primates, rather than in quadrupedal terrestrial primates. [8]

Other mammals

In ungulates (hoofed mammals) the forelimb is optimized for speed and endurance by a combination of length of stride and rapid step; the proximal forelimb segments are short with large muscles, while the distal segments are elongated with less musculature. In two of the major groups of ungulates, odd-toed and even-toed ungulates, what remain of the "hands" — the metacarpal and phalangeal bones — are elongated to the extent that they serve little use beyond locomotion. The giraffe, the largest even-toed ungulate, has large terminal phalanges and fused metacarpal bones able to absorb the stress from running. [9]

The sloth spend its life hanging upside-down from branches, and has highly specialized third and fourth digits for the purpose. They have short and squat proximal phalanges with much longer terminal phalanges. They have vestigial second and fifth metacarpals, and their palm extends to the distal interphalangeal joints. The arboreal specialization of these terminal phalanges makes it impossible for the sloth to walk on the ground where the animal has to drag its body with its claws. [9]

-

Distal phalanges of a Masai giraffe

-

Three-fingered sloth

-

Terminal phalanx of a Scelidotherium ground sloth

History

The term phalanx or phalanges refers to an ancient Greek army formation in which soldiers stand side by side, several rows deep, like an arrangement of fingers or toes.

Additional images

-

Phalanges.

-

Phalanges.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle and tarsometarsal joints. Bones of foot.Deep dissection.

-

Ankle and tarsometatarsal joint. Deep dissection.Anterior view

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection. Posterior view.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection.Anterior, palmar, view.

-

Wrist joint. Deep dissection.Anterior, palmar, view.

-

Interphalangeal ligaments and phalanges.Right hand. Deep dissection. Posterior (dorsal) view.

See also

References

- ^ Premkumar, Kalyani (2012). Anatomy & Physiology: The Massage Connection. Baltimore, MD. ISBN 978-0-7817-5922-9

- ^ a b c d Almécija, Moyà-Solà & Alba 2010

- ^ a b Gray, Henry (1918). "6b. 3. The Phalanges of the Hand". Anatomy of the Human Body. ISBN 0-8121-0644-X.

- ^ a b "Apical Phalangeal Tufts". Center for Academic Research & Training in Anthropogeny. Retrieved February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Shrewsbury & Johnson 1975, p. 784

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). "6d. 3. The Phalanges of the Foot". Anatomy of the Human Body. ISBN 0-8121-0644-X.

- ^ a b Mittra et al. 2007

- ^ Hamrick 1998

- ^ a b Gough-Palmer, MacLachlan & Routh 2008

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011727, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0011727instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1148/rg.282075061 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1148/rg.282075061instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9637179, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9637179instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17657781, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17657781instead. - Shrewsbury, M; Johnson, RK (1975). "The Fascia of the Distal Phalanx" (PDF). J Bone Joint Surg Am. (57): 784–788.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)