Cowpea: Difference between revisions

→Culinary use: Nutrition additions |

Lead and other changes |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

|Common Names}} |

|Common Names}} |

||

The '''cowpea''' |

The '''cowpea''', ''Vigna unguiculata'', is an [[Annual plant|annual]] [[Herbaceous plant|herbaceous]] [[legume]] from the genus ''[[Vigna]]''. Four subspecies are recognised, of which three are cultivated. There is a high level of [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]] diversity found within the species with large variations in the size, shape and structure of the plant. Cowpeas can be erect, semi erect ([[Trailing plant|trailing]]) or [[Climbing plant|climbing]]. The crop is mainly grown for its seeds, which are extremely high in [[Protein (nutrient)|protein]], although the leaves and immature seed pods can also be consumed. |

||

Due to its tolerance for sandy soil and low rainfall it is an important crop in the [[Semi-arid climate|semi-arid]] regions across Africa and other countries. It requires very few inputs, as the plants [[root nodule]]s are able to [[Nitrogen fixation|fix atmospheric nitrogen]], making it a valuable crop for resource poor farmers and [[intercropping]]. The whole plant can also be used as [[forage]] for animals, with its use as cow feed likely responsible for its name. |

|||

Cowpeas are one of the most important food [[legume]] crops in the semiarid tropics covering Asia, Africa, southern Europe, and Central and South America. A drought-tolerant and warm-weather crop, cowpeas are well-adapted to the drier regions of the tropics, where other food legumes do not perform well. It also has the useful ability to [[Nitrogen fixation|fix atmospheric nitrogen]] through its [[root nodule]]s, and it grows well in poor soils with more than 85% sand and with less than 0.2% organic matter and low levels of phosphorus.<ref>{{Cite journal| pages = 169–150| year = 2003| doi = 10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00148-5| volume = 84| journal = Field Crops Research | first1 = B.| last2 = Ajeigbe | first2 = H. A.| last3 = Tarawali | first3 = S. A.| last4 = Fernandez-Rivera | first4 = S.| last5 = Abubakar | first5 = M.| title = Improving the production and utilization of cowpea as food and fodder| last1 = Singh}}</ref> In addition, it is shade tolerant, so is compatible as an [[intercrop]] with [[maize]], [[millet]], [[sorghum]], [[sugarcane]], and [[cotton]]. This makes cowpeas an important component of traditional intercropping systems, especially in the subsistence farming systems of the dry [[savanna]]s in sub-Saharan Africa.<ref>Blade, 2005{{Specify|date=August 2008}}</ref> In these systems the haulm (dried stalks) of cowpea is a valuable by-product, used as animal feed. |

|||

Cultivated cowpeas are known by the common names [[black-eye pea]], southern pea, [[yardlong bean]], [[catjang]], and crowder pea. They were [[Domestication|domesticated]] in Africa and are one of the oldest crops to be farmed. A second domestication event probably occurred in Asia, before they spread into Europe and the Americas. The seeds are usually cooked and made into stews and curries, or ground into flour or paste. |

|||

Research in Ghana found that selecting early generations of cowpea crops to increase yield is not an effective strategy. Francis Padi from the Savannah Agricultural Research Institute in Tamale, Ghana, writing in ''Crop Science'', suggests other methods such as bulk breeding are more efficient in developing high-yield varieties.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.scidev.net/en/sub-suharan-africa/news/sub-saharan-africa-news-in-brief-25-march-9-april.html |title=Sub-Saharan Africa news in brief: 25 March–9 April |accessdate=2008-04-13 |last=Scott |first=Christina |date=2008-04-10 |work=SciDev.Net |publisher=[[Science and Development Network]] |doi= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |quote= }}</ref> |

|||

Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in [[Nigeria]] and [[Niger]] which account for 66% of world cowpea production. A 1997 estimate suggests that cowpeas are cultivated on 12.5 million hectares, have a worldwide production of 3 million tonnes and consumed by 200 million people on a daily basis.<ref name=":16" /> Insect infestation is a major constraint to the production of cowpea, potentially responsible for over 90% loss in yield.<ref name=":3" /> The legume pod borer ''[[Maruca vitrata]],'' is the main pre-harvest pest of the cowpea and the cowpea weevil [[Callosobruchus maculatus|''Callosobruchus'' ''maculatus'']] the main post-harvest ''pest.'' |

|||

According to the USDA food database, the leaves of the cowpea plant have the highest percentage of calories from protein among [[vegetarianism|vegetarian]] foods.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://smarterfitter.com/2007/10/28/100-most-protein-rich-vegetarian-foods/ |title=100 Most Protein Rich Vegetarian Foods |accessdate=2008-04-06 |last=Shaw |first=Monica |date=2007-10-28 |work=SmarterFitter Blog |doi= |archiveurl= |archivedate= |quote= }}</ref> |

|||

== Taxonomy and etymology == |

== Taxonomy and etymology == |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

There is a large [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]] diversity found within the crop, and the growth conditions and grower preferences for each variety vary from region to region.<ref name=":2" /> |

There is a large [[Morphology (biology)|morphological]] diversity found within the crop, and the growth conditions and grower preferences for each variety vary from region to region.<ref name=":2" /> However, as the plant is primarily [[Self-pollination|self pollinating]] its [[genetic diversity]] within varieties is relatively low.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Egbadzor|first=Kenneth F|last2=Ofori|first2=Kwadwo|last3=Yeboah|first3=Martin|last4=Aboagye|first4=Lawrence M|last5=Opoku-Agyeman|first5=Michael O|last6=Danquah|first6=Eric Y|last7=Offei|first7=Samuel K|date=2014-09-20|title=Diversity in 113 cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp] accessions assessed with 458 SNP markers|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4190189/|journal=SpringerPlus|volume=3|doi=10.1186/2193-1801-3-541|issn=2193-1801|pmc=PMC4190189|pmid=25332852}}</ref> Cowpeas can either be short and bushy (as short {{Convert|20|cm|in}} or act like a vine by climbing supports or trailing along the ground (to a height of {{Convert|2|m|ft}}.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web|url=https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_viun.pdf|title=Plant guide for cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) .|last=Sheahan|first=C. M.|date=2012|website=USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ|archive-url=|archive-date=|dead-url=|access-date=}}</ref><ref name=":17">{{Cite book|url=https://www.nap.edu/read/11763/chapter/7#115|title=5 Cowpea {{!}} Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables {{!}} The National Academies Press|language=en|doi=10.17226/11763}}</ref> The [[Taproot|tap root]] can penetrate to a depth of {{Convert|2.4|m|ft}} after eight weeks.<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/afcm/cowpea.html|title=Cowpea|website=www.hort.purdue.edu|access-date=2017-04-13}}</ref> |

||

The size and shape of the leaves varies greatly, making this an important feature for classifying and distinguishing cowpea varieties.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Pottorff|first=Marti|last2=Ehlers|first2=Jeffrey D.|last3=Fatokun|first3=Christian|last4=Roberts|first4=Philip A.|last5=Close|first5=Timothy J.|date=2012-01-01|title=Leaf morphology in Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp]: QTL analysis, physical mapping and identifying a candidate gene using synteny with model legume species|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-234|journal=BMC Genomics|volume=13|pages=234|doi=10.1186/1471-2164-13-234|issn=1471-2164|pmc=3431217|pmid=22691139}}</ref> Another distinguishing feature of cowpeas are the long {{Convert|20-50|cm|in|8-20=}} [[Peduncle (botany)|peduncles]] which hold the flowers and seed pods. One peduncle can support four or more seed pods.<ref name=":8" /> |

The size and shape of the leaves varies greatly, making this an important feature for classifying and distinguishing cowpea varieties.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Pottorff|first=Marti|last2=Ehlers|first2=Jeffrey D.|last3=Fatokun|first3=Christian|last4=Roberts|first4=Philip A.|last5=Close|first5=Timothy J.|date=2012-01-01|title=Leaf morphology in Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp]: QTL analysis, physical mapping and identifying a candidate gene using synteny with model legume species|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-234|journal=BMC Genomics|volume=13|pages=234|doi=10.1186/1471-2164-13-234|issn=1471-2164|pmc=3431217|pmid=22691139}}</ref> Another distinguishing feature of cowpeas are the long {{Convert|20-50|cm|in|8-20=}} [[Peduncle (botany)|peduncles]] which hold the flowers and seed pods. One peduncle can support four or more seed pods.<ref name=":8" /> Flower colour varies through different shade of purple, pink, yellow and white and blue.<ref name=":17" /> |

||

Seeds and seed pods from wild cowpeas are very small,<ref name=":8" /> while cultivated varieties can have pods {{Convert| |

Seeds and seed pods from wild cowpeas are very small,<ref name=":8" /> while cultivated varieties can have pods between {{Convert|10 and 110|cm|in}} long.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Rawal|first=Kanti M.|date=1975-11-01|title=Natural hybridization among wild, weedy and cultivated Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00132908|journal=Euphytica|language=en|volume=24|issue=3|pages=699–707|doi=10.1007/BF00132908|issn=0014-2336}}</ref> A pod can contain 6-13 seeds that are usually kidney shaped, although the seeds become more spherical the more restricted they are within the pod.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":8" /> Their texture and colour is very diverse. They can have a smooth or rough coat, and be speckled, mottled or blotchy. Colours include white, cream, green, red, brown and black or various combinations.<ref name=":8" /> |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

agronomic traits. ''Journal Sci. Res. Dev., ,'' 10''', '''111-118.</ref> New research using [[Molecular marker|molecular markers]] has suggested that domestication may have instead occurred in East Africa and currently both theories are generally accepted.<ref name=":9" /> |

agronomic traits. ''Journal Sci. Res. Dev., ,'' 10''', '''111-118.</ref> New research using [[Molecular marker|molecular markers]] has suggested that domestication may have instead occurred in East Africa and currently both theories are generally accepted.<ref name=":9" /> |

||

While it may be uncertain when cultivation began |

While it may be uncertain when cultivation began it is considered one of the oldest domesticated crops.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Chivenge|first=Pauline|last2=Mabhaudhi|first2=Tafadzwanashe|last3=Modi|first3=Albert T.|last4=Mafongoya|first4=Paramu|date=2017-04-16|title=The Potential Role of Neglected and Underutilised Crop Species as Future Crops under Water Scarce Conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4483666/|journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health|volume=12|issue=6|pages=5685–5711|doi=10.3390/ijerph120605685|issn=1661-7827|pmc=PMC4483666|pmid=26016431}}</ref> Remains of charred cowpeas from rock shelters in Central Ghana have been dated to the [[2nd millennium BC|second millennium BCE]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=D'Andrea|title=Early domesticated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from Central Ghana|journal=Antiquity|date=September 1, 2007|volume=81|issue=313|pages=686–698|doi=10.1017/S0003598X00095661|url=http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=9437336|accessdate=20 May 2016|display-authors=etal}}</ref> In 2300 BC the cowpea is believed to have made its way into South East Asia where secondary domestication events may have occurred.<ref name=":1">PERRINO, P., LAGHETTI, G., SPAGNOLETTI ZEULI, P. L. & MONTI, L.M. (1993) Diversification of cowpea in the Mediterranean and other centres of cultivation. ''Genetic resources and crop evolution, ''40''',''' 121-132.</ref> From there they traveled north to the Mediterranean, where they were used by the Greeks and Romans.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=XMA9gYIj-C4C&pg=PA508&lpg=PA508&dq=cowpea+cultivation+history+greek+rome&source=bl&ots=nJTc5-rcCs&sig=Bsy4ZjgnveP3WbqRC6L8CkbpDM0&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiTuabOwqLTAhWMpZQKHWPDDHwQ6AEIJTAB#v=onepage&q=cowpea%20cultivation%20history%20greek%20rome&f=false|title=Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, Two Volume Set|last=Ensminger|first=Marion Eugene|last2=Ensminger|first2=Audrey H.|date=1993-11-09|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=9780849389801|language=en}}</ref> The first written references to the cowpea were in 300BC and they probably reached Central and North America during the [[slave trade]] through the 17th to early 19th centuries.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":0" /> |

||

== Cultivation == |

== Cultivation == |

||

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

== Production and consumption == |

== Production and consumption == |

||

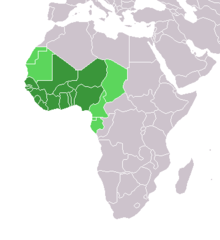

Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in Nigeria and Niger which account for 66% of world cowpea production.<ref name=":4">[http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor 24/01/2015 FAO 2012 FAOSTAT Gateway] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906230329/http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor |date=September 6, 2015 }}</ref> The Sahel region also contains other major producers such as [[Burkina Faso]], [[Ghana]], [[Senegal]] and [[Mali]]. |

Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in [[Nigeria]] and [[Niger]] which account for 66% of world cowpea production.<ref name=":4">[http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor 24/01/2015 FAO 2012 FAOSTAT Gateway] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906230329/http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor |date=September 6, 2015 }}</ref> The Sahel region also contains other major producers such as [[Burkina Faso]], [[Ghana]], [[Senegal]] and [[Mali]]. Niger is the main exporter of cowpeas and Nigeria the main importer. Exact figures for cowpea production are hard to come up with as it is not a major export crop. A 1997 estimate suggests that cowpeas are cultivated on 12.5 million hectares and have a worldwide production of 3 million tonnes.<ref name=":2" /> While they play a key role in subsistence farming and livestock fodder, the cowpea is also seen as a major cash crop by Central and West African farmers, with an estimated 200 million people consuming cowpea on a daily basis.<ref name=":16">LANGYINTUO, A. S., LOWENBERG-DEBOER, J., FAYE, M., LAMBERT, D., IBRO, G., MOUSSA, B., KERGNA, A., KUSHWAHA, S., MUSA, S. & NTOUKAM, G. (2003) Cowpea supply and demand in West and Central Africa. ''Field Crops Research,'' 82''',''' 215-231.</ref> |

||

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), as of 2012, the average cowpea yield in Western Africa was an estimated 483 kg/ha,<ref name=":4" /> which is still 50% below the estimated potential production yield.<ref>KORMAWA, P. M., CHIANU, J. N. & MANYONG, V. M. (2002) Cowpea demand and supply patterns in West Africa: the case of Nigeria. IN FATOKUN, C. A., TARAWALI, S. A., SINGH, B. B., KORMAWA, P. M. & TAMO, M. (Eds.) ''Challenges and Opportunities for enhancing sustainable Cowpea production.'' International Institute of Tropical Agriculture.</ref> In some tradition cropping methods the yield can be as low as 100 kg/ha. |

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), as of 2012, the average cowpea yield in Western Africa was an estimated 483 kg/ha,<ref name=":4" /> which is still 50% below the estimated potential production yield.<ref>KORMAWA, P. M., CHIANU, J. N. & MANYONG, V. M. (2002) Cowpea demand and supply patterns in West Africa: the case of Nigeria. IN FATOKUN, C. A., TARAWALI, S. A., SINGH, B. B., KORMAWA, P. M. & TAMO, M. (Eds.) ''Challenges and Opportunities for enhancing sustainable Cowpea production.'' International Institute of Tropical Agriculture.</ref> In some tradition cropping methods the yield can be as low as 100 kg/ha. |

||

Revision as of 01:35, 16 April 2017

| Cowpea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cowpeas | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | V. unguiculata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vigna unguiculata | |

| Synonyms[1][2][3] | |

|

List

| |

The cowpea, Vigna unguiculata, is an annual herbaceous legume from the genus Vigna. Four subspecies are recognised, of which three are cultivated. There is a high level of morphological diversity found within the species with large variations in the size, shape and structure of the plant. Cowpeas can be erect, semi erect (trailing) or climbing. The crop is mainly grown for its seeds, which are extremely high in protein, although the leaves and immature seed pods can also be consumed.

Due to its tolerance for sandy soil and low rainfall it is an important crop in the semi-arid regions across Africa and other countries. It requires very few inputs, as the plants root nodules are able to fix atmospheric nitrogen, making it a valuable crop for resource poor farmers and intercropping. The whole plant can also be used as forage for animals, with its use as cow feed likely responsible for its name.

Cultivated cowpeas are known by the common names black-eye pea, southern pea, yardlong bean, catjang, and crowder pea. They were domesticated in Africa and are one of the oldest crops to be farmed. A second domestication event probably occurred in Asia, before they spread into Europe and the Americas. The seeds are usually cooked and made into stews and curries, or ground into flour or paste.

Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in Nigeria and Niger which account for 66% of world cowpea production. A 1997 estimate suggests that cowpeas are cultivated on 12.5 million hectares, have a worldwide production of 3 million tonnes and consumed by 200 million people on a daily basis.[4] Insect infestation is a major constraint to the production of cowpea, potentially responsible for over 90% loss in yield.[5] The legume pod borer Maruca vitrata, is the main pre-harvest pest of the cowpea and the cowpea weevil Callosobruchus maculatus the main post-harvest pest.

Taxonomy and etymology

Vigna unguiculata is a member of the Vigna (peas or beans) genus.[6] Unguiculata is Latin for "with a small claw", which reflects the small stalks on the flower petals.[7] All cultivated cowpeas are found within the universally accepted V. unguiculata subspecies unguiculata classification, which is then commonly divided into four cultivar groups: Unguiculata, Biflora, Sesquipedalis, and Textilis.[8][9] Some well-known common names for cultivated cowpeas include black-eye pea, southern pea, yardlong bean, catjang, and crowder pea.[6] The classification of the wild relatives within V. unguiculata is more complicated, with over 20 different names having been used and between 3 and 10 subgroups described.[8][10] The original subgroups of stenophylla, dekindtiana and tenuis appear to be common in all taxonomic treatments, while the variations pubescens and protractor were raised to sub-species level by a 1993 charactisation.[8][11]

The first written reference of the word 'cowpea' appeared in 1798 in the United States.[7] The name was most likely acquired due to their use as a fodder crop for cows.[12] Black-eyed pea, a common name used for the unguiculata cultivar group, describes the presence of a distinctive black spot at the hilum of the seed. Black-eyed peas were first introduced to the southern states in the United States and some early varieties had peas squashed closely together in their pods, leading to the other common names of southern pea and crowder-pea.[7] Sesquipedalis in Latin means "foot and a half long", and this subspecies which arrived in the United States via Asia is characterised by unusually long pods, leading to the common names of yardlong bean, asparagus bean and Chinese long-bean.[13]

|

Group |

Common name[6] |

|---|---|

| Unguiculata | crowder-pea, southern pea, black-eyed pea |

| Biflora | catjang, sow-pea |

| Sesquipedalis | yardlong bean, asparagus bean, Chinese long-bean |

| Textilis |

Description

There is a large morphological diversity found within the crop, and the growth conditions and grower preferences for each variety vary from region to region.[8] However, as the plant is primarily self pollinating its genetic diversity within varieties is relatively low.[14] Cowpeas can either be short and bushy (as short 20 centimetres (7.9 in) or act like a vine by climbing supports or trailing along the ground (to a height of 2 metres (6.6 ft).[15][16] The tap root can penetrate to a depth of 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) after eight weeks.[17]

The size and shape of the leaves varies greatly, making this an important feature for classifying and distinguishing cowpea varieties.[18] Another distinguishing feature of cowpeas are the long 20–50 centimetres (7.9–19.7 in)* peduncles which hold the flowers and seed pods. One peduncle can support four or more seed pods.[17] Flower colour varies through different shade of purple, pink, yellow and white and blue.[16]

Seeds and seed pods from wild cowpeas are very small,[17] while cultivated varieties can have pods between 10 and 110 centimetres (3.9 and 43.3 in) long.[19] A pod can contain 6-13 seeds that are usually kidney shaped, although the seeds become more spherical the more restricted they are within the pod.[15][17] Their texture and colour is very diverse. They can have a smooth or rough coat, and be speckled, mottled or blotchy. Colours include white, cream, green, red, brown and black or various combinations.[17]

History

Compared to most other important crops, little is known about the domestication, dispersal and cultivation history of the cowpea.[20] Although there is no archaeological evidence for early cowpea cultivation the centre of diversity of the cultivated cowpea is West Africa, leading an early consensus that this is the likely centre of origin and place of early domestication.[21] New research using molecular markers has suggested that domestication may have instead occurred in East Africa and currently both theories are generally accepted.[20]

While it may be uncertain when cultivation began it is considered one of the oldest domesticated crops.[22] Remains of charred cowpeas from rock shelters in Central Ghana have been dated to the second millennium BCE.[23] In 2300 BC the cowpea is believed to have made its way into South East Asia where secondary domestication events may have occurred.[9] From there they traveled north to the Mediterranean, where they were used by the Greeks and Romans.[24] The first written references to the cowpea were in 300BC and they probably reached Central and North America during the slave trade through the 17th to early 19th centuries.[9][21]

Cultivation

Cowpeas thrive in poor dry conditions, growing well in soils up to 85% sand.[25] This makes them a particularly important crop in arid, semi-desert regions where not many other crops will grow. As well as an important source of food for humans in poor arid regions the crop can also be used as feed for livestock. This predominately occurs in India, where the stock is fed cowpea as forage or fodder.[8] It's nitrogen fixing ability means that as well as functioning as a sole-crop, the cowpea can be effectively intercropped with sorghum, millet, maize, cassava or cotton.[26]

The optimum temperature for cowpea growth is 30 °C (86 °F), making it only available as a summer crop for most of the world. It grows best in regions with an annual rainfall of between 400–700 millimetres (16–28 in). The ideal soils are sandy and it has better tolerance for infertile and acid soil than most other crops. Generally 133,000 seeds are planted per hectare for the erect varieties and 60,000 per hectare for the climbing and trailing varieties. The grain can be harvested after about 100 days or the whole plant used as forage after approximately 120 days. Leaves can be picked from 4 weeks after planting.[27]

These characteristics, along with its low fertilisation requirements, make the cowpea an ideal crop for resource poor farmers living in the Sahel region of West Africa. Early maturing varieties of the crop can thrive in the semi-arid climate, where rainfall is often less than 500mm per year. The timing of planting is crucial as the plant must mature during the seasonal rains.[28] The crop is mostly intercroped with pearl millet and plants are selected that provide both grain and fodder value instead of the more specialised varieties.[29]

Storage of the grains can be problematic in Africa due to potential infestation by post-harvest pests. Traditional methods of protecting stored grain include using the insecticidal properties of Neem extracts, mixing the grain with ash or sand, using vegetable oils, combining ash and oil into a soap solution or treating the cowpea pods with smoke or heat.[30] More modern methods include storage in airtight containers, using gamma irradiation, or heating or freezing the grain.[31] Temperatures of 60°C kill the weevil larvae, leading to a recent push to develop cheap forms of solar heating that can be used to treat stored grain.[32] One of the more recent developments is the use a cheap reusable double bagging system that asphyxiates the cowpea weevils.[33]

Pests and diseases

Insects are a major factor in the low yields of African cowpea crops, and they affect each tissue component and developmental stage of the plant. In bad infestations insect pressure is responsible for over 90% loss in yield.[5] The legume pod borer Maruca vitrata, is the main pre-harvest pest of the cowpea.[34] Other important pests include pod sucking bugs, thrips and the post-harvest weevil Callosobruchus maculatus.[5]

M. vitrata, the Maruca pod borer, causes the most damage to the growing cowpea due to their large host range and cosmopolitan distribution.[35] It causes damage to the flower buds, flowers and pods of the plant with infestations resulting in a 20-88% loss of yield.[35] While the insect can cause damage through all growth stages, most of the damage occurs during flowering.[35] Biological control has had limited success, so most preventative methods rely on the use of agrichemicals. Genetically modified cowpeas are currently being developed to express the cry protein from Bacillus thuringiensis., which is toxic to Lepidoteran species including the Maruca.[36]

Severe cowpea weevil, C. maculatus, infestations can affect 100% of the stored peas and cause up to 60% grain loss within a few months.[37][38] The bruchid generally enters the cowpea pod through holes pre-harvest and lays eggs on the dry seed.[39] The larvae burrow there way into the seed, feeding on the endosperm. The weevil develops into a sexually mature adult within the seed.[40] An individual bruchid will lay 20-40 eggs, and in optimal conditions each egg can develop into a reproductively active adults in 3 weeks.[41] The most common methods of protection involve the use of insecticides, the main pesticides used being carbomates, synthetic pyrethoids and organophosphates.[42]

Cowpea is susceptible to a number of nematode, fungal, bacterial and virus diseases, which can result in substantial loss in yield.[43] Common diseases include blights, root rot, wilt, powdery mildew, root knot, rust and leaf spot.[44] The plant is also susceptible to mosaic viruses, which is characterisd by a green mosaic pattern in the leaves.[44] The cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) was first discovered in 1959 and since then it has become an important biological tool in scientific research.[45] CPMV is very stable and easy to propagate to a high yield, making it useful in vector development and protein expression systems.[45] One of the plants defenses against some insect attacks is the cow pea trypsin inhibitor (CpTI).[46] CpTI is the only gene obtained outside of B. thuringiensis that has been inserted into a commercially available genetically modified crop.[47]

Culinary use

Cowpeas are grown mostly for their edible beans, although the leaves, green peas and green pea pods can also be consumed, meaning the cowpea can be used as a food source before the dried peas are harvested.[48] Like other legumes cowpea grain is cooked to make it edible, usually by boiling them. [49] Cowpeas can be prepared in stews, soups, purees and casseroles,[50][51] but the most common way to eat them is in curries.[50] They can also be processed into a paste or flour.[52] Chinese long beans can be eaten raw or cooked, but as they easily become waterlogged are usually sautéed, stir-fried, or deep-fried.[53]

A common snack in Africa is Koki or Moyin-Moyin, where the cowpeas are mashed into a paste and then wrapped in banana leaves.[54] In Africa cowpeas are also used as to supplement infant formula when weaning babies off milk.[55] Slaves brought to America and the West Indies cooked cowpea much the same way as they did in Africa, although much of the American South considered cowpeas not suitable for human consumption.[56] A popular dish was called Hoppin' John, which contained black-eyed peas cooked with spicy sausages, ham hock, pork, rice and tomato sauce. Over time cowpeas became more universally accepted and now Hoppin' John is seen as a traditional Southern dish ritually served on New Years day.[57]

Nutrition and health

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 336 kJ (80 kcal) |

60.03 g | |

| Sugars | 6.9 g |

| Dietary fiber | 10.6 g |

1.26 g | |

23.52 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 3 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 71% 0.853 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 17% 0.226 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 13% 2.075 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 21% 0.357 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 158% 633 μg |

| Vitamin C | 2% 1.5 mg |

| Vitamin K | 4% 5 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 8% 110 mg |

| Iron | 46% 8.27 mg |

| Magnesium | 44% 184 mg |

| Phosphorus | 34% 424 mg |

| Potassium | 37% 1112 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 16 mg |

| Zinc | 31% 3.37 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 11.95 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[58] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[59] | |

Cowpeas seeds provide a rich source of proteins and calories, as well as minerals and vitamins.[52] This complements the mainly cereal diet in countries that grow cowpeas as a major food crop.[60] A seed can consist of 25% protein and has very low fat content.[61] Cowpea starch is digested slower than the starch from cereals, which is more benefcial to human health.[52] The grain is one of the richest source of folic acid, an important vitamin that helps prevent neural tube defects in unborn babies.[62]

The cowpea has often been referred to as "poor man’s meat" due to the high levels of protein found in the seeds and leaves.[49] However, it does contain some anti-nutritional elements, notable phytic acid and protease inhibitors, which reduces the nutritional value of the crop.[52] Although little research has been conducted on the nutritional value of the leaves and immature pods, what is available suggests that the leaves have a similar nutrition value to black nightshade and sweet potato leaves, while the green pods have less anti-nutritional factors than the dried seeds.[52]

Production and consumption

Most cowpeas are grown on the African continent, particularly in Nigeria and Niger which account for 66% of world cowpea production.[63] The Sahel region also contains other major producers such as Burkina Faso, Ghana, Senegal and Mali. Niger is the main exporter of cowpeas and Nigeria the main importer. Exact figures for cowpea production are hard to come up with as it is not a major export crop. A 1997 estimate suggests that cowpeas are cultivated on 12.5 million hectares and have a worldwide production of 3 million tonnes.[8] While they play a key role in subsistence farming and livestock fodder, the cowpea is also seen as a major cash crop by Central and West African farmers, with an estimated 200 million people consuming cowpea on a daily basis.[4]

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), as of 2012, the average cowpea yield in Western Africa was an estimated 483 kg/ha,[63] which is still 50% below the estimated potential production yield.[64] In some tradition cropping methods the yield can be as low as 100 kg/ha.

Outside Africa, the major production areas are Asia, Central America, and South America. Brazil is the world's second-leading producer of cowpea seed, producing 600,000 tonnes annually.[65] The amount of protein content of cowpea's leafy parts consumed annually in Africa and Asia is equivalent to 5 million tonnes of dry cowpea seeds, representing as much as 30% of the total food legume production in the lowland tropics.[66]

References

- ^ "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species".

- ^ "International Plant Names Index, entry for Vigna sinensis".

- ^ "International Plant Names Index, entry for Pl. Jav. Rar. (Hasskarl)".

- ^ a b LANGYINTUO, A. S., LOWENBERG-DEBOER, J., FAYE, M., LAMBERT, D., IBRO, G., MOUSSA, B., KERGNA, A., KUSHWAHA, S., MUSA, S. & NTOUKAM, G. (2003) Cowpea supply and demand in West and Central Africa. Field Crops Research, 82, 215-231.

- ^ a b c JACKAI, L. E. N. & DAOUST, R. A. (1986) Insect pests of cowpeas. Annual Review of Entomology, 31, 95-119.

- ^ a b c "COWPEA.NET – Main – TaxonomyAndRelatedSpecies". cowpea.net.

- ^ a b c Top 100 Food Plants By Ernest Small page 104

- ^ a b c d e f SINGH, B. B., MOHAN, D. R., DASHIELL, K. E. & JACKAI, L. E. N. (1997) Advances in Cowpea Research, IITA, Ibadan Nigeria, International Institutre of Tropical Agriculture

- ^ a b c PERRINO, P., LAGHETTI, G., SPAGNOLETTI ZEULI, P. L. & MONTI, L.M. (1993) Diversification of cowpea in the Mediterranean and other centres of cultivation. Genetic resources and crop evolution, 40, 121-132.

- ^ Theoretical and Applied Genetics May 1999, Volume 98, Issue 6-7, pp 1104–1119 Genetic relationships among subspecies of Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. based on allozyme variation R. S. Pasquet

- ^ This appears to be one of the latest taxonomical classifications

- ^ 3 Cowpea Michael P. Timko Jeff D. Ehlers Philip A. Roberts

- ^ Ensminger, Marion; Ensminger, Audrey (1993). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia. Florida: CRC Press. p. 2363. ISBN 0-8493-8980-1.

- ^ Egbadzor, Kenneth F; Ofori, Kwadwo; Yeboah, Martin; Aboagye, Lawrence M; Opoku-Agyeman, Michael O; Danquah, Eric Y; Offei, Samuel K (2014-09-20). "Diversity in 113 cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L) Walp] accessions assessed with 458 SNP markers". SpringerPlus. 3. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-541. ISSN 2193-1801. PMC 4190189. PMID 25332852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Sheahan, C. M. (2012). "Plant guide for cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) " (PDF). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b 5 Cowpea | Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables | The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/11763.

- ^ a b c d e "Cowpea". www.hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ^ Pottorff, Marti; Ehlers, Jeffrey D.; Fatokun, Christian; Roberts, Philip A.; Close, Timothy J. (2012-01-01). "Leaf morphology in Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp]: QTL analysis, physical mapping and identifying a candidate gene using synteny with model legume species". BMC Genomics. 13: 234. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-234. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 3431217. PMID 22691139.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rawal, Kanti M. (1975-11-01). "Natural hybridization among wild, weedy and cultivated Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp". Euphytica. 24 (3): 699–707. doi:10.1007/BF00132908. ISSN 0014-2336.

- ^ a b Xiong, Haizheng; Shi, Ainong; Mou, Beiquan; Qin, Jun; Motes, Dennis; Lu, Weiguo; Ma, Jianbing; Weng, Yuejin; Yang, Wei (2016-08-10). "Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp)". PLOS ONE. 11 (8): e0160941. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160941. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4980000. PMID 27509049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b OGUNKANMI, L. A., TAIWO, A., MOGAJI, O. L., AWOBODEDE, A., EZIASHI, E. E. & OGUNDIPE, O. T. (2005/2006) Assessment of genetic diversity among cultivated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) cultivars from a range of localities across West Africa using agronomic traits. Journal Sci. Res. Dev., , 10, 111-118.

- ^ Chivenge, Pauline; Mabhaudhi, Tafadzwanashe; Modi, Albert T.; Mafongoya, Paramu (2017-04-16). "The Potential Role of Neglected and Underutilised Crop Species as Future Crops under Water Scarce Conditions in Sub-Saharan Africa". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 12 (6): 5685–5711. doi:10.3390/ijerph120605685. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 4483666. PMID 26016431.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ D'Andrea; et al. (September 1, 2007). "Early domesticated cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) from Central Ghana". Antiquity. 81 (313): 686–698. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00095661. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Ensminger, Marion Eugene; Ensminger, Audrey H. (1993-11-09). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, Two Volume Set. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849389801.

- ^ OBATOLU, V. A. (2003) Growth pattern of infants fed with a mixture of extruded malted maize and cowpea. Nutrition, 19,174-178.

- ^ BLADE, S. F., SHETTY, S. V. R., TERAO, T. & SINGH, B. B. (1997) Recent developments in cowpea cropping systems research. IN SINGH, B.B., MOHAN RAJ, D. R., DASHIELL, K. E. & JACKAI, L. E. N. (Eds.) Advances in Cowpea Research. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture and Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences.

- ^ "Production guidelines for Cowpeas" (PDF). South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Dugje, I.Y.; Omoigui, L.O.; Ekeleme, F; Kamara, A.Y.; Ajeigbe, H. (2009). "Farmers' Guide to Cowpea Production in West Africa". International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. Ibadan, Nigeria.

- ^ Ibaraki), Matsunaga, R.(Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences, Tsukuba,; B.B., Singh,; M., Adamou,; S., Tobita,; K., Hayashi,; A., Kamidohzono, (2006-01-01). "Cowpea [Vigna unguiculata] cultivation on the Sahelian region of west Africa: Farmers' preferences and production constraints". Japanese Journal of Tropical Agriculture (Japan). ISSN 0021-5260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Poswal, M. A. T.; Akpa, A. D. (1991-01-01). "Current trends in the use of traditional and organic methods for the control of crop pests and diseases in Nigeria". Tropical Pest Management. 37 (4): 329–333. doi:10.1080/09670879109371609. ISSN 0143-6147.

- ^ "Toxicity and repellence of African plants traditionally used for the protection of stored cowpea against Callosobruchus maculatus". Journal of stored products research. 40 (4). ISSN 0022-474X.

- ^ Murdock, L. L.; Shade, R. E. (1991-10-01). "Eradication of Cowpea Weevil (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)in Cowpeas by Solar Heating". American Entomologist. 37 (4): 228–231. doi:10.1093/ae/37.4.228. ISSN 1046-2821.

- ^ Baributsa, D.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Murdock, L.; Moussa, B. (2010-09-21). "Profitable chemical-free cowpea storage technology for smallholder farmers in Africa: opportunities and challenges". Julius-Kühn-Archiv (in German). 0 (425): 1046. doi:10.5073/jka.2010.425.340. ISSN 2199-921X.

- ^ SHARMA, H. C. (1998) Bionomics, host plant resistance, and management of the legume pod borer, Maruca vitrata. Crop Protection, 17, 373-386.

- ^ a b c Jayasinghe, R.C.; Premachandra, W.T.S. Dammini; Neilson, Roy (2015-09-21). "A study on Maruca vitrata infestation of Yard-long beans (Vigna unguiculata subspecies sesquipedalis)". Heliyon. 1 (1). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2015.e00014. ISSN 2405-8440. PMC 4939760. PMID 27441212.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Agunbiade, Tolulope A.; Coates, Brad S.; Datinon, Benjamin; Djouaka, Rousseau; Sun, Weilin; Tamò, Manuele; Pittendrigh, Barry R. (2014-03-19). "Genetic Differentiation among Maruca vitrata F. (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Populations on Cultivated Cowpea and Wild Host Plants: Implications for Insect Resistance Management and Biological Control Strategies". PLoS ONE. 9 (3). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092072. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3960178. PMID 24647356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kang, Jung Koo; Pittendrigh, Barry R.; Onstad, David W. (2013-12-01). "Insect resistance management for stored product pests: a case study of cowpea weevil (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)". Journal of Economic Entomology. 106 (6): 2473–2490. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 24498750.

- ^ Tarver, Matthew R; Shade, Richard E; Shukle, Richard H; Moar, William J; Muir, William M; Murdock, Larry M; Pittendrigh, Barry R (2007-05-01). "Pyramiding of insecticidal compounds for control of the cowpea bruchid (Callosobruchus maculatus F.)". Pest Management Science. 63 (5): 440–446. doi:10.1002/ps.1343. ISSN 1526-4998.

- ^ Mashela, P; Pofu, K (2012). "Storing cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) seeds in active cattle kraals for suppression of Callosobruchus maculates". African Journal of Biotechnology. 11: 14713–14715.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth (1988-02-01). "Egg laying decisions by the bean weevil Callosobruchus maculatus". Ecological Entomology. 13 (1): 107–118. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1988.tb00338.x. ISSN 1365-2311.

- ^ Murdock, Larry L.; Seck, Dogo; Ntoukam, Georges; Kitch, Laurie; Shade, R. E. (2003-05-01). "Preservation of cowpea grain in sub-Saharan Africa—Bean/Cowpea CRSP contributions". Field Crops Research. Research Highlights of the Bean/Cowpea Collaborative Research Support Program, 1981 - 2002. 82 (2–3): 169–178. doi:10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00036-4.

- ^ Jackai, L. E. N.; Adalla, C. B. (1997). "800x600 Pest management practices in cowpea: a review.". In Singh, B. B. (ed.). Advances in Cowpea Research. IITA. pp. 240–258. ISBN 9789781311109.

- ^ "The control of weed, pest and disease complexes in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) by the application of pesticides singly and in combination - ScienceDirect". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ a b "Southern Pea (Blackeye, Cowpea) | Texas Plant Disease Handbook". plantdiseasehandbook.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ a b Sainsbury, Frank; Cañizares, M. Carmen; Lomonossoff, George P. (2010-08-05). "Cowpea mosaic Virus: The Plant Virus–Based Biotechnology Workhorse". http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114242. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114242. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Use of cowpea trypsin inhibitor (CpTI) to protect plants against insect predation - ScienceDirect". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2017-04-15.

- ^ Wu, Hongsheng; Zhang, Yuhong; Liu, Ping; Xie, Jiaqin; He, Yunyu; Deng, Congshuang; Clercq, Patrick De; Pang, Hong (2014-04-21). "Effects of Transgenic Cry1Ac + CpTI Cotton on Non-Target Mealybug Pest Ferrisia virgata and Its Predator Cryptolaemus montrouzieri". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e95537. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095537. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3994093. PMID 24751821.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ EHLERS, J. D. & HALL, A. E. (1997) Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.). Field Crops Res., 53, 187-204.

- ^ a b Hamid, Saima; Muzaffar, Sabeera; Wani, Idrees Ahmed; Masoodi, Farooq Ahmad; Bhat, Mohd. Munaf (2016-06-01). "Physical and cooking characteristics of two cowpea cultivars grown in temperate Indian climate". Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences. 15 (2): 127–134. doi:10.1016/j.jssas.2014.08.002.

- ^ a b "Cowpeas Recipe". African Foods. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ "Africa Imports - African Recipes - Red-Red Stew". africaimports.com. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ a b c d e Gonçalves, Alexandre; Goufo, Piebiep; Barros, Ana; Domínguez‐Perles, Raúl; Trindade, Henrique; Rosa, Eduardo A. S.; Ferreira, Luis; Rodrigues, Miguel (2016-07-01). "Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp), a renewed multipurpose crop for a more sustainable agri‐food system: nutritional advantages and constraints". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 96 (9): 2941–2951. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7644. ISSN 1097-0010.

- ^ "The Long and the Short of Yard-Long Beans". Food52. 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ "Koki - The Congo Cookbook (African recipes) www.congocookbook.com -". www.congocookbook.com. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ Oyeleke, O. A.; Morton, I. D.; Bender, A. E. (1985-09-01). "The use of cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata) in improving a popular Nigerian weaning food". The British Journal of Nutrition. 54 (2): 343–347. ISSN 0007-1145. PMID 4063322.

- ^ Covey, Herbert C.; Eisnach, Dwight (2009-01-01). What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways from the Slave Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313374975.

- ^ Severson, Kim (2015-12-29). "Field Peas, a Southern Good Luck Charm". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

- ^ PHILLIPS, R. D., MCWATTERS, K. H., CHINNAN, M. S., HUNG, Y. C., BEUCHAT, L. R., SEFA-DEDEH, S., SAKYI-DAWSON, E., NGODDY, P., NNANYELUGO, D. & ENWERE, J. (2003) Utilization of cowpeas for human food. Field Crops Res., 82, 193-213.

- ^ RANGEL, A., DOMONT, G. B., PEDROSA, C. & FERREIRA, S. T. (2003) Functional properties of purified vicilins from cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) and pea (Pisum sativum) and cowpea protein isolate. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 51, 5792-5797.

- ^ Witthöft, C.; Hefni, M. (2016-01-01). Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Oxford: Academic Press. pp. 724–730. ISBN 9780123849533.

- ^ a b 24/01/2015 FAO 2012 FAOSTAT Gateway Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ KORMAWA, P. M., CHIANU, J. N. & MANYONG, V. M. (2002) Cowpea demand and supply patterns in West Africa: the case of Nigeria. IN FATOKUN, C. A., TARAWALI, S. A., SINGH, B. B., KORMAWA, P. M. & TAMO, M. (Eds.) Challenges and Opportunities for enhancing sustainable Cowpea production. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture.

- ^ (Quazzelli 1988).

- ^ (Steele, et al. 1985)