Cholecystectomy: Difference between revisions

→Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Cholecystectomy: Added links, improved readability |

→Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Cholecystectomy: Added citations |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

====Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Cholecystectomy==== |

====Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Cholecystectomy==== |

||

Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery ([[Natural_orifice_transluminal_endoscopic_surgery|NOTES]]) is an experimental technique where the laparoscope is passed through natural orifices and internal incisions, rather than skin incisions, to access to the abdominal cavity. This offers the potential to eliminate visible scars. Since 2007, cholecystectomy by NOTES has been performed anecdotally via transgastric and transvaginal routes. The risk of [[Gastrointestinal_perforation|gastrointestinal leak]], difficulty visualizing the abdominal cavity and other technical limitations currently limit further clinical adoption of NOTES for cholecystectomy. |

Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery ([[Natural_orifice_transluminal_endoscopic_surgery|NOTES]]) is an experimental technique where the laparoscope is passed through natural orifices and internal incisions, rather than skin incisions, to access to the abdominal cavity.<ref name="Gaillard">{{cite journal|last1=Gaillard|first1=M|last2=Tranchart|first2=H|last3=Lainas|first3=P|last4=Dagher|first4=I|title=New minimally invasive approaches for cholecystectomy: Review of literature.|journal=World journal of gastrointestinal surgery|date=27 October 2015|volume=7|issue=10|pages=243-8|doi=10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.243|pmid=26523212}}</ref> This offers the potential to eliminate visible scars.<ref name="Chamberlain" /> Since 2007, cholecystectomy by NOTES has been performed anecdotally via transgastric and transvaginal routes.<ref name="Gaillard" /> The risk of [[Gastrointestinal_perforation|gastrointestinal leak]], difficulty visualizing the abdominal cavity and other technical limitations currently limit further clinical adoption of NOTES for cholecystectomy.<ref name="Chamberlain">{{cite journal|last1=Chamberlain|first1=RS|last2=Sakpal|first2=SV|title=A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy.|journal=Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract|date=September 2009|volume=13|issue=9|pages=1733-40|doi=10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y|pmid=19412642}}</ref> |

||

===Open cholecystectomy=== |

===Open cholecystectomy=== |

||

Revision as of 11:10, 20 March 2018

| Cholecystectomy | |

|---|---|

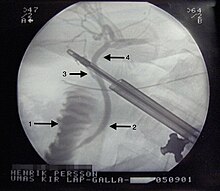

Cholangiogram (X-Ray) during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. 1 - Duodenum. 2 - Common bile duct. 3 - Cystic duct. 4 - Hepatic duct. The gallbladder is not seen as the cystic duct is occluded by the surgeon. | |

| Pronunciation | /ˌkɒləsɪsˈtɛktəmi/ |

| ICD-9-CM | 575.0 |

| MeSH | D002763 |

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. The operation is performed either laparoscopically, using a video camera, or via an open surgical technique. There are advantages and disadvantages to each operation.[1][page needed]

The surgery is typically very successful in relieving symptoms that people have, but up to 10% of people may continue to experience similar symptoms, which has been termed postcholecystectomy syndrome.[2] Additionally, there can be serious complications of cholecystectomy, such as bile duct injury, retained or dropped gall stones, abscess formation and narrowing (stenosis) of the bile duct.[2] In 2011, cholecystectomy was the 8th most common operating room procedure performed in hospitals in the United States.[3]

Medical use

Pain caused by gallstones, infection, and gallbladder cancer are common reasons for removal of the gallbladder. The gallbladder can also be removed in order to treat biliary dyskinesia or gallbladder cancer.[4]

Biliary colic

Biliary colic, or pain caused by gallstones, occurs when a gallstone temporarily blocks the bile duct that drains the gallbladder.[5] Typically, pain from biliary colic is felt in the right upper part of the abdomen, is moderate to severe, and goes away on its own after a few hours when the stone dislodges.[6] Gallstones are incredibly common but most people with gallstones will never have biliary colic or need surgery. Of the more than 20 million people in the US with gallstones, only about 30% will go on to require cholecystectomy.[7] 50–80 % of the patients with gallstones have no symptoms, and their stones are noticed incidentally on imaging tests of the abdomen (such as ultrasound or CT) done for some other reason.[8] However, once symptoms develop, more than 90% of people will have a repeat attack in the next 10 years.[9] Repeated attacks of biliary colic are the most common reason for removing the gallbladder, and lead to about 300,000 cholecystectomies in the US each year.[10][11]

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis, or inflammation of the gallbladder caused by interruption in the normal flow of bile, is another common reason for cholecystectomy.[12] Pain in cholecystitis is similar to that of biliary colic, but lasts longer than 6 hours and occurs together with signs of infection such as fever, chills, or an elevated white blood cell count.[9] People with cholecystitis will also usually have a positive Murphy sign on physical exam.[9]

Acute cholecystitis is the most common complication of gallstone disease, and 90-95% of acute cholecystitis is caused by gallstones blocking drainage of the gallbladder.[13] If the blockage is incomplete and the stone passes quickly, the person experiences biliary colic. If the gallbladder is completely blocked and remains so for a prolonged period, the person develops acute cholecystitis.[14]

The remaining 5-10% of acute cholecystitis occurs in people without gallstones, and for this reason is called acalculous cholecystitis. It usually develops in people who have abnormal bile drainage secondary to a serious illness, such as people with multi-organ failure, serious trauma, recent major surgery, or following a long stay in the intensive care unit.[14]

Cholecystitis may be acute or chronic. Chronic cholecystitis develops after multiple, repeat episodes of acute cholecystitis change the normal anatomy of the gallbladder.[14]

Gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer (also called carcinoma of the gallbladder) is a rare indication for cholecystectomy. In cases where cancer is suspected, the open technique for cholecystectomy is usually performed.[10]

Other indications

Removal of the gallbladder is also used to prevent the relapse of pancreatitis that is caused by gallstones that block the common bile duct.[12]: 940, 1017

Contraindications

There are no specific contraindications for this procedure, but anyone who cannot tolerate general surgery should not receive it. People can be split into high and low risk groups using a tool such as the ASA physical status classification system. In this system, people who are ASA categories III, IV, and V are considered high risk for cholecystectomy. Typically this means people who cannot tolerate general anesthesia, who have end-stage liver disease with portal hypertension, or whose blood does not clot properly.[4] This subset of people should not have a cholecystectomy. Alternatives to surgery are briefly mentioned below.

Risks and complications

All surgery carries risk of serious complications or even death. The operative death rate in cholecystectomy is about 0.1% in people under age 50 and about 0.5% in people over age 50.[15]

The most serious complication of cholecystectomy is damage to the bile ducts.[1][page needed] In laparoscopic cholecystectomy, this occurs in between 0.3% and 0.6% of cases.[1][page needed] Approximately 25-30% of biliary injuries are typically noticed intraoperatively during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the rest during the early post-operative period.[1][page needed] Damage to the duct that causes leakage typically manifests as either fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain several days following cholecystectomy or manifests in laboratory studies as rising total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase.[1][page needed]

Leakage from the stump of the cystic duct is a complication that is more common with the laparoscopic approach than the open approach but is still rare, occurring in less than 1% of procedures; it is treated by drainage followed by insertion of a bile duct stent.[16]

Procedure

In cholecystectomy, the cystic duct and cystic artery are identified and dissected, then ligated with clips and cut for removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is most commonly performed using a laparoscopic technique but can also be performed as an open surgery.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

By 2013, laparoscopic cholecystectomy had replaced open cholecystectomy as the first-choice of treatment for people with uncomplicated gallstones and acute cholecystitis.[17][18] Laparoscopic surgery has fewer complications, takes less time to recover from, and allows patients to leave the hospital and return to their normal activities sooner compared to open cholecystectomy.[19] Outcomes are as good or better than open procedures as long as the surgeon is well-trained in laparoscopic methods. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has also been shown to have decreased mortality, decreased morbidity, and decreased cardiac and respiratory complications.[20]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy requires several (usually 4) small incisions in the abdomen to allow the insertion of operating ports, small cylindrical tubes approximately 5 to 10 mm in diameter, through which surgical instruments are placed into the abdominal cavity. The surgeon inflates the abdominal cavity with carbon dioxide to create a working space. The laparascope, an instrument with a video camera and light source at the end, illuminates the surgical field and sends a magnified image from inside the abdomen to a video monitor, giving the surgeon a clear view of the organs and tissues. The surgeon performs the operation by manipulating the surgical instruments through the operating ports. The gallbladder fundus is identified, grasped, and retracted superiorly. With a second grasper, the gallbladder infundibulum is retracted laterally to expose and open Calot's Triangle (cystic artery, cystic duct, and common hepatic duct). The triangle is gently dissected to clear the peritoneal covering and obtain a view of the underlying structures. The cystic duct and the cystic artery are identified, ligated with titanium clips and cut. Then the gallbladder is dissected away from the liver bed and removed through one of the ports. [18]

Single Incision Laparascopic Cholecystecomy

Laparoendoscopic Single Site Surgery (LESS) or Single Incision Laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) is an technique in which a single cut is made through the navel, instead of the 3-4 four small different cuts used in standard laparoscopy. There appears to be a cosmetic benefit over conventional four-hole laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and no advantage in postoperative pain and hospital stay compared with standard laparascopic procedures.[21] There is no scientific consensus regarding risk for bile duct injury with SILS versus traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[21]

Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Cholecystectomy

Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) is an experimental technique where the laparoscope is passed through natural orifices and internal incisions, rather than skin incisions, to access to the abdominal cavity.[22] This offers the potential to eliminate visible scars.[23] Since 2007, cholecystectomy by NOTES has been performed anecdotally via transgastric and transvaginal routes.[22] The risk of gastrointestinal leak, difficulty visualizing the abdominal cavity and other technical limitations currently limit further clinical adoption of NOTES for cholecystectomy.[23]

Open cholecystectomy

Sometimes people need open surgery instead of laparascopy. In open cholecystectomy, a surgical incision of around 8 to 12 cm is made below the edge of the right rib cage and the gallbladder is removed through this large opening, typically using electrocautery.[18] The liver is retracted superiorly, and a top-down approach is taken (from the fundus towards the neck) to remove the gallbladder from the liver.[18][12]: 696 This is done if the person has severe cholecystitis, emphysematous gallbladder, fistulization of gallbladder and gallstone ileus, cholangitis, cirrhosis or portal hypertension, and blood dyscrasias.

Sometimes problems arise during the laparoscopic procedure -- for example, the person has unusual anatomy and the surgeon cannot see well enough through the camera, or it looks like the person has cancer -- and the laparascopy is stopped and the person is opened up with a larger incision instead.[18]

Open cholecystectomy is associated with greater post-operative pain, longer hospital length of stay, increased use of antibiotics, and a longer proportion of time out of work than a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[24]

Biopsy

After removal, the gallbladder should be sent for pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis and look for any incidental cancer. Incidental cancer of the gallbladder is found in approximately 1% of cholecystectomies.[12]: 1019 If cancer is present in the gallbladder, it's usually necessary to re-operate to remove parts of the liver and lymph nodes and test them for additional cancer.[25]

Long-term prognosis

In 95% of people undergoing cholecystectomy as treatment for simple biliary colic, removing the gallbladder completely resolves their symptoms.[11]

Up to 40% of people who undergo cholecystectomy develop a condition called postcholecystectomy syndrome, or PCS.[2] Symptoms are typically similar to the pain and discomfort prior to cholecystectomy and most commonly include gastrointestinal distress (dyspepsia) and persistent pain in the upper right abdomen.[2]

Some people following cholecystectomy may develop diarrhea.[4] The cause is unclear, but is presumed to involve the disturbance to the bile system. The disturbance is thought to be due to increased speed of enterohepatic recycling of bile salts, causing the terminal ileum to be unable to absorb them all.[4] This overwhelmed portion of the intestine leads to diarrhea.[4] Most cases resolve within weeks or a few months, though in rare cases the condition may last for years. It can be controlled with medication such as cholestyramine.[26]

Special populations and considerations

Pregnancy

It is generally safe for pregnant women to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy during any trimester of pregnancy.[8] Early elective surgery is recommended for women with symptomatic gallstones to decrease risk of spontaneous abortion and pre-term delivery.[8] Without cholecystectomy, more than half will have recurrent symptoms during their pregnancy, and nearly one in four will develop a complication requiring urgent surgery, such as acute cholecystitis.[8] Acute cholecystitis is the second most common cause of acute abdomen in pregnant women after appendectomy.[14]

Porcelain gallbladder

Porcelain gallbladder (PGB), a condition where the gallbladder wall shows calcification on imaging tests, was previously considered a reason to remove the gallbladder because it was thought that people with this condition had a high risk of developing gallbladder cancer.[9] However, more recent studies have shown that there is no strong association between gallbladder cancer and porcelain gallbladder, and that PGB alone is not a strong enough indication for a prophylactic cholecystectomy.[8]

Alternatives to surgery

There are several alternatives to cholecystectomy for people who do not want surgery, or in whom the benefits of surgery would outweigh the risks. These include:

- Conservative management, or a "watch and wait" approach that involves treating symptoms as-needed with oral medications. This is the preferred treatment for people with gallstones but no symptoms based on expert opinion.[8] Conservative management may also be appropriate for people with mild biliary colic, as the pain from colic can be managed with pain medications like NSAIDS (ex: ketorolac) or opioids.[9]

- ERCP, short for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, an endoscopic procedure that can remove gallstones or prevent blockages by widening parts of the bile duct where gallstones frequently get stuck. For this procedure, an endoscope, or small, long thin tube with a camera on the end, is passed through the mouth and down the throat. The doctor advances the camera through the stomach and into the first part of the small intestine to reach the opening of the bile duct. The doctor can inject a special, radiopaque dye through the endoscope into the bile duct to see stones or other blockages on x-ray.[27] ERCP does not require general anaesthesia and can be done outside of the operating room. While ERCP can be used to remove a specific stone that is causing a blockage to allow drainage, it cannot remove all stones in the gallbladder.

- Cholecystostomy, or drainage of an infected gallbladder via insertion of a small tube through the abdominal wall, can be an option for people who are too sick to have a full surgery under general anaesthesia, but need immediate drainage of the gallbladder.

Epidemiology

About 600,000 people receive a cholecystectomy in the United States each year.[12]: 855

In a study of Medicaid-covered and uninsured U.S. hospital stays in 2012, cholecystectomy was the most common operating room procedure.[28]

History

German Surgeon Wilhelm Fabry in 1618 removed the first gallstone from a living person.[29] The first elective cholecystectomy was performed in 1882 by Carl Langenbuch.[30] In September 12,1985, Erich Mühe performed the world's first laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[31]Introduced in 1987 by Phillipe Mouret in France, the laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a less invasive surgery than an open cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now considered the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic gallstones.[30][32]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Greenfield's surgery : scientific principles & practice. Mulholland, Michael W.,, Lillemoe, Keith D.,, Doherty, Gerard M.,, Upchurch, Gilbert R.,, Alam, Hasan B.,, Pawlik, Timothy M., (Sixth edition ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9781469890012. OCLC 933274207.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d Jaunoo, S.S.; Mohandas, S.; Almond, L.M. "Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCS)". International Journal of Surgery. 8 (1): 15–17. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.10.008.

- ^ "Characteristics of Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2011 - Statistical Brief #170". www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ a b c d e Sabiston textbook of surgery : the biological basis of modern surgical practice. Townsend, Courtney M., Jr.,, Beauchamp, R. Daniel,, Evers, B. Mark, 1957-, Mattox, Kenneth L., 1938- (20th edition ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9780323299879. OCLC 951748294.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Gallstones". NIDDK. November 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Internal Clinical Guidelines Team (October 2014). "Gallstone Disease: Diagnosis and Management of Cholelithiasis, Cholecystitis and Choledocholithiasis. Clinical Guideline 188": 21. PMID 25473723.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Doherty, Gerard M. (2015). Doherty, Gerard M. (ed.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (14 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ^ a b c d e f Agresta, Ferdinando; Campanile, Fabio Cesare; Vettoretto, Nereo; Silecchia, Gianfranco; Bergamini, Carlo; Maida, Pietro; Lombari, Pietro; Narilli, Piero; Marchi, Domenico (May 2015). "Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: consensus conference-based guidelines". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 400 (4): 429–453. doi:10.1007/s00423-015-1300-4. ISSN 1435-2451. PMID 25850631.

- ^ a b c d e Abraham, Sherly; Rivero, Haidy G.; Erlikh, Irina V.; Griffith, Larry F.; Kondamudi, Vasantha K. (2014-05-15). "Surgical and Nonsurgical Management of Gallstones". American Family Physician. 89 (10). ISSN 0002-838X.

- ^ a b Essential surgical procedures. Velasco, Jose M.,. [Philadelphia, PA]. ISBN 9780323375672. OCLC 949278311.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Doherty, Gerard M. (2015). Doherty, Gerard M. (ed.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (14 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ^ a b c d e Goldman, Lee (2011). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 1437727883.

- ^ Kimura, Yasutoshi; Takada, Tadahiro; Strasberg, Steven M.; Pitt, Henry A.; Gouma, Dirk J.; Garden, O. James; Büchler, Markus W.; Windsor, John A.; Mayumi, Toshihiko (January 2013). "TG13 current terminology, etiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Sciences. 20 (1): 8–23. doi:10.1007/s00534-012-0564-0. ISSN 1868-6982. PMID 23307004.

- ^ a b c d Kimura, Yasutoshi; Takada, Tadahiro; Kawarada, Yoshifumi; Nimura, Yuji; Hirata, Koichi; Sekimoto, Miho; Yoshida, Masahiro; Mayumi, Toshihiko; Wada, Keita (2007). "Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 14 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y. ISSN 0944-1166. PMC 2784509. PMID 17252293.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Doherty, Gerard M. (2015). Doherty, Gerard M. (ed.). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery (14 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ^ Siiki, A; Rinta-Kiikka, I; Sand, J; Laukkarinen, J (May 2015). "Biodegradable biliary stent in the endoscopic treatment of cystic duct leak after cholecystectomy: the first case report and review of literature". Journal of laparoendoscopic & advanced surgical techniques. Part A. 25 (5): 419–22. doi:10.1089/lap.2015.0068. PMID 25853929.

- ^ Coccolini, Federico; Catena, Fausto; Pisano, Michele; Gheza, Federico; Fagiuoli, Stefano; Saverio, Salomone Di; Leandro, Gioacchino; Montori, Giulia; Ceresoli, Marco. "Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Surgery. 18: 196–204. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.04.083.

- ^ a b c d e Shackelford's surgery of the alimentary tract. Yeo, Charles J., (Eighth edition ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 0323402321. OCLC 1003489504.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Yamashita, Yuichi; Takada, Tadahiro; Kawarada, Yoshifumi; Nimura, Yuji; Hirota, Masahiko; Miura, Fumihiko; Mayumi, Toshihiko; Yoshida, Masahiro; Strasberg, Steven (2007-01). "Surgical treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 14 (1): 91–97. doi:10.1007/s00534-006-1161-x. PMC 2784499. PMID 17252302.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Antoniou, Stavros A (2014-12-14). "Meta-analysis of laparoscopicvsopen cholecystectomy in elderly patients". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (46). doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Lirici, Marco Maria; Tierno, Simone Maria; Ponzano, Cecilia (October 2016). "Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: does it work? A systematic review". Surgical Endoscopy. 30 (10): 4389–4399. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-4757-5. ISSN 1432-2218. PMID 26895901.

- ^ a b Gaillard, M; Tranchart, H; Lainas, P; Dagher, I (27 October 2015). "New minimally invasive approaches for cholecystectomy: Review of literature". World journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 7 (10): 243–8. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.243. PMID 26523212.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Chamberlain, RS; Sakpal, SV (September 2009). "A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy". Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 13 (9): 1733–40. doi:10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y. PMID 19412642.

- ^ Glavić, Ž; Begić, L.; Šimleša, D.; Rukavina, A. (2001-04-01). "Treatment of acute cholecystitis". Surgical Endoscopy. 15 (4): 398–401. doi:10.1007/s004640000333. ISSN 0930-2794.

- ^ Kapoor VK (March 2001). "Incidental gallbladder cancer". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96 (3): 627–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03597.x. PMID 11280526.

- ^ Chronic diarrhea: A concern after gallbladder removal?, Mayo Clinic

- ^ "ERCP: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ^ Lopez-Gonzalez L, Pickens GT, Washington R, Weiss AJ (October 2014). "Characteristics of Medicaid and Uninsured Hospitalizations, 2012". HCUP Statistical Brief #183. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ^ Odze and Goldblum surgical pathology of the GI tract, liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. Odze, Robert D.,, Goldblum, John R., (Third edition ed.). Philadelphia, PA. ISBN 9781455707478. OCLC 889211538.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Schwartz's principles of surgery. Schwartz, Seymour I., 1928-, Brunicardi, F. Charles,, Andersen, Dana K.,, Billiar, Timothy R.,, Dunn, David L.,, Hunter, John G., (Tenth edition ed.). [New York]. ISBN 9780071796750. OCLC 892490454.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Reynolds, Walker Jr. (2001). "The First Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy". Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 5 (1): 89–94.

- ^ Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy : an Evidence-based Guide. Agresta, Ferdinando,, Campanile, Fabio Cesare,, Vettoretto, Nereo,. Cham [Switzerland]. ISBN 9783319054070. OCLC 880422516.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: others (link)