Dogu'a Tembien: Difference between revisions

→Culture: included subsection on siwa |

|||

| Line 233: | Line 233: | ||

== Culture == |

== Culture == |

||

=== ''Awrus'' === |

|||

Tembien's frenetic ''Awrus'' dancing style<ref name=Briggs>Philip Briggs, ''Ethiopia: The Bradt Travel Guide'', 3rd edition (Chalfont St Peters: Bradt, 2002), p. 270</ref><ref name="smidt">{{cite book |last1=Smidt |first1=W. |title=A Short History and Ethnography of the Tembien Tigrayans |publisher=SpringerNature |location=Cham, Switzerland |pages=63-78 |url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_4}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

In almost every household of Dogu'a Tembien, the woman knows how to prepare the local beer, ''[[Siwa (beer)|siwa]]''. Ingredients are water, a home-baked and toasted flat bread commonly made from [[barley]] in the highlands,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Fetien Abay |last2=Waters-Bayer |first2=A. |last3=Bjørnstad |first3=Å. |title=Farmers' seed management and innovation in varietal selection: implications for barley breeding in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia |journal=Ambio |date=2008 |volume=37 |issue=4 |pages=312-321 |url=https://bioone.org/journals/AMBIO-A-Journal-of-the-Human-Environment/volume-37/issue-4/0044-7447(2008)37[312:FSMAII]2.0.CO;2/Farmers-Seed-Management-and-Innovation-in-Varietal-Selection--Implications/10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[312:FSMAII]2.0.CO;2.short}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ayimut Kiros-Meles |last2=Abang |first2=M. |title=Farmers’ knowledge of crop diseases and control strategies in the Regional State of Tigrai, northern Ethiopia: implications for farmer–researcher collaboration in disease management |journal=Agriculture and Human Values |date=2008 |url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10460-007-9109-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Yemane Tsehaye |last2=Bjørnstad |first2=Å. |last3=Fetien Abay |title=Phenotypic and genotypic variation in flowering time in Ethiopian barleys |journal=Euphytica |date=2012 |volume=188 |issue=3 |pages=309-323 |url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10681-012-0764-3}}</ref> and from [[sorghum]], [[finger millet]] or [[maize]] in the lower areas,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Alemtsehay Tsegay |last2=Berhanu Abrha |last3=Getachew Hruy |title=Major Crops and Cropping Systems in Dogu’a Tembien |date=2019 |publisher=Springer |pages=403-413 |url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_27}}</ref> some yeast (''[[Saccharomyces cerevisiae]]''),<ref name="lee">{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=M. |last2=Meron Regu |last3=Semeneh Seleshe |title=Uniqueness of Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverage of plant origin, ''tella'' |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |date=2015 |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=110-114 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352618115000426}}</ref> and dried leaves of ''gesho'' (''[[Rhamnus prinoides]]'') that serve as a [[catalyser]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Abadi Berhane |title=Gesho (Rhamnus prinoides) cultivation in Northern Ethiopia, Tigray |url=https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abadi_Girmay2/publication/280776180_Gesho/links/55c623e408aeb97567439ab5/Gesho.pdf |accessdate=25 July 2019}}</ref> The brew is allowed to ferment for a few days, after which it is served, sometimes with the pieces of bread floating on it (the customer will gently blown them to one side of the beaker). The alcoholic content is 2% to 5%.<ref name="lee"/> Most of the coarser part of the brew, the ''atella'', remains back and is used as cattle feed.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nyssen |first1=J., and colleagues |title=Cattle Breeds, Milk Production, and Transhumance in Dogu’a Tembien |date=2019 |publisher=SpringerNature |location=Cham, Switzerland |pages=415-428 |url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_27}}</ref> |

|||

''Siwa'' is consumed during social events, after (manual) work, and as an incentive for farmers and labourers. There are about a hundred traditional beer houses (''[[Siwa (beer)|Inda Siwa]]''), often in unique settings, all across Dogu'a Tembien. |

|||

== Surrounding woredas== |

== Surrounding woredas== |

||

Revision as of 04:36, 28 July 2019

Degua Tembien

ደጉዓ ተምቤን | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Region | Tigray |

| Zone | Mehakelegnaw (Central) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,852.89 km2 (715.40 sq mi) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 113,595 |

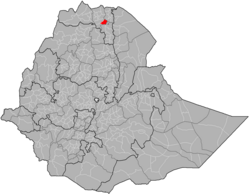

Degua Tembien (Tigrinya: ደጉዓ ተምቤን, "Upper Tembien", commonly transliterated as Dogu'a Tembien) is one of the woredas in the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. It is named in part after the former province of Tembien. Part of the Mehakelegnaw Zone, Degua Tembien is bordered on the south by the Debub Misraqawi (South Eastern) Zone, on the west by Abergele, on the north by Kola Tembien, and on the east by the Misraqawi (Eastern) Zone. The administrative center of this woreda is Hagere Selam.

Geography

Topography and landscapes

Major mountains

- Tsatsen, 2815 metres, a wide mesa between Hagere Selam and Inda Maryam Qorar (13°37′N 39°10′E / 13.617°N 39.167°E)

- Ekli Imba, 2799 metres, summit of the Arebay massif in Arebay tabia or district (13°43′N 39°16′E / 13.717°N 39.267°E)

- Imba Zuw’ala, 2710 metres, near Hagere Selam (13°39′N 39°11′E / 13.650°N 39.183°E)

- Aregen, 2660 metres, in Aregen tabia (13°37′N 39°5′E / 13.617°N 39.083°E)

- Dabba Selama, 2630 metres, in Haddinnet tabia (13°43′N 39°12′E / 13.717°N 39.200°E) (not to be confused with the homonymous monastery)

- Imba Dogu’a, 2610 metres, in Mizane Birhan tabia (13°37′N 39°16′E / 13.617°N 39.267°E)

- Imba Ra’isot, 2590 metres, in Ayninbirkekin tabia (13°40′N 39°15′E / 13.667°N 39.250°E)

- Itay Sara, 2460 metres, in Haddinnet tabia (13°43′N 39°10′E / 13.717°N 39.167°E)

- Imba Bete Giyergis, 2390 metres, in Debre Nazret tabia (13°30′N 39°19′E / 13.500°N 39.317°E)

- Tsili, 2595 metres, in Haddinnet tabia (13°44′N 39°11′E / 13.733°N 39.183°E)

Lowest places

The lowest places are where the main rivers leave the district. They are often located not far from the highest points, what indicates the magnitude of the relief

- Along Giba River, near Kemishana, 1406 metres (13°29′N 39°07′E / 13.483°N 39.117°E)

- Along Agefet River, north of Azef, 1728 metres (13°48′N 39°14′E / 13.800°N 39.233°E)

- Along Tsaliet River, underneath the promontory that holds Dabba Selama monastery, 1763 metres (13°42′N 39°05′E / 13.700°N 39.083°E)

- At the junction of Tanqwa and Tsech’i Rivers, a bit upstream from May Lomin, 1897 metres (13°37′N 39°01′E / 13.617°N 39.017°E)

Mountain passes

Since ages, major footpaths and roads in Dogu’a Tembien have been using mountain passes, called ksad, what means “neck” in Tigrinya language.

- Ksad Halah (13°40′N 39°15′E / 13.667°N 39.250°E), a narrow pass between Giba and Tsaliet basins, also crossed by the main road

- Ksad Miheno (13°40′N 39°13′E / 13.667°N 39.217°E), another pass with several footpaths linking Giba and Tsaliet basins; here, the main road is a ridge road and crosses the pass transversally

- Ksad Addi Amyuk (13°39.3′N 39°10.3′E / 13.6550°N 39.1717°E), at 2710 metres, is the highest pass of the district, where the main road passes before entering Hagere Selam

- Ksad Mederbay (13°38.75′N 39°15.3′E / 13.64583°N 39.2550°E), a V-shaped pass in a dolerite ridge, used to be the main entrance gate to Dogu’a Tembien, when coming from Mekelle with many converging footpaths and mule tracks. It was also a battle field during the Ethiopian Civil War of the 1980s

- Ksad Azef (13°44.2′N 39°13′E / 13.7367°N 39.217°E) is a place through which the Tembien highlands could relatively easily be accessed when coming from the Gheralta lowlands. During the Italian invasion, it was an important battlefield during the First Battle of Tembien – The Italians called it Passo Abaro

- Ksad Adawro (13°37.6′N 39°9.25′E / 13.6267°N 39.15417°E) is not a real pass, but a relatively level ledge between two cliffs

- The town of Hagere Selam is located on a wide saddle

- Ksad Korowya (13°42.16′N 39°7.3′E / 13.70267°N 39.1217°E), remotely located along Tsaliet River, is a spectacular pass in the sandstone landscape, to be crossed before ascending to Dogu’a Tembien from the northwest

Administrative division

Dogu’a Tembien comprises 24 tabias or municipalities (status 2019)

- Hagere Selam, woreda capital (13°38.9′N 39°10.7′E / 13.6483°N 39.1783°E)

- Degol Woyane, tabia centre in Zala (13°40′N 39°6′E / 13.667°N 39.100°E)

- Mahbere Sillasie, tabia centre in Guderbo (13°39′N 39°9′E / 13.650°N 39.150°E)

- Selam, tabia centre in Addi Werho (13°40′N 39°12′E / 13.667°N 39.200°E)

- Haddinnet, tabia centre in Addi Idaga (13°42′N 39°12′E / 13.700°N 39.200°E)

- Addi Walka, tabia centre in Kelkele (13°43′N 39°18′E / 13.717°N 39.300°E)

- Arebay, tabia centre in Arebay village (13°43′N 39°17′E / 13.717°N 39.283°E)

- Ayninbirkekin, tabia centre in Halah (13°40′N 39°14′E / 13.667°N 39.233°E)

- Addilal, tabia centre in Addilal village (13°41′N 39°19′E / 13.683°N 39.317°E)

- Addi Azmera, tabia centre in Tukhul (13°38′N 39°20′E / 13.633°N 39.333°E)

- Emni Ankelalu, tabia centre in Mitslal Afras (13°39′N 39°22′E / 13.650°N 39.367°E)

- Mizane Birhan, tabia centre in Ma’idi (13°37′N 39°16′E / 13.617°N 39.267°E)

- Mika’el Abiy, tabia centre in Megesta (13°37′N 39°12′E / 13.617°N 39.200°E)

- Lim’at, tabia centre in Maygua (13°37′N 39°8′E / 13.617°N 39.133°E)

- Melfa, tabia centre in Melfa village (13°38′N 39°8′E / 13.633°N 39.133°E), birthplace of Ethiopian emperor Yohannes IV

- Aregen, tabia centre in Addi Gotet (13°37′N 39°6′E / 13.617°N 39.100°E)

- Menachek, tabia centre in Addi Bayro (13°35′N 39°5′E / 13.583°N 39.083°E)

- Mizan, tabia centre in Kerene (13°35′N 39°3′E / 13.583°N 39.050°E). This tabia includes Arefa (13°35.4′N 39°1.7′E / 13.5900°N 39.0283°E), reputedly birthplace of the Queen of Sheba

- Simret, tabia centre in Dengolo (13°34′N 39°7′E / 13.567°N 39.117°E). This tabia includes the village of Mennawe (13°00′N 39°00′E / 13.000°N 39.000°E), birthplace of Ethiopian general Ras Alula Abba Nega

- Seret, tabia centre in Inda Maryam Qorar (13°35′N 39°8′E / 13.583°N 39.133°E)

- Walta, tabia centre in Da’erere (13°35′N 39°11′E / 13.583°N 39.183°E)

- Inda Sillasie, tabia centre in Migichi (13°33′N 39°12′E / 13.550°N 39.200°E)

- Amanit, tabia centre in Addi Qeshofo village (13°33′N 39°15′E / 13.550°N 39.250°E)

- Debre Nazret, tabia centre in Togogwa (13°34′N 39°18′E / 13.567°N 39.300°E)

Population

Some 127,000 people live in Dogu’a Tembien, with 56% below the age of 20. There are almost equal numbers of men and women. The population density is 122 people per km² (2010 data).[2][3] As in many low-income countries, he population pyramid has a wide base. There is however a timid onset of a demographic transition, in relation to the changing position of women in the society and improved health services. The Family Code of 2000 advocates gender equality; hence, the marriageable age was raised from 15 to 18 years old. Women rights impose sharing the assets that the household has accumulated. Female genital mutilation, child marriage, abduction and domestic violence are now considered to be crimes. Almost all children are scholarised but girls may interrupt when reaching the age of 13 to 15 years, in relation to absence of facilities for menstrual hygiene management in the schools.[2]

Based on the 2007 national census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this woreda had a total population of 113,595, an increase of 28% over the 1994 census, of whom 56,955 were men and 56,640 women; 7,270 or 6.4% were urban inhabitants. A total of 25,290 households were counted in this woreda, resulting in an average of 4.5 persons per household, and 24,591 housing units. The majority of the inhabitants said they practiced Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, with 99.89% reporting that as their religion.[4]

The 1994 national census reported a total population for this woreda of 89,037, of whom 44,408 were men and 44,629 were women. The largest ethnic group reported in Degua Tembien was the Tigrayan (99.87%). Tigrinya was spoken as a first language by 99.89%. Concerning education, 7% of the population were considered literate, which was less than the Zone average of 14%; 8% of children aged 7-12 were in primary school; 0.14% of the children aged 13-14 were in junior secondary school, and 0.21% of the inhabitants aged 15-18 were in senior secondary school. Concerning sanitary conditions, about 29% of the urban houses and 15% of all houses had access to safe drinking water at the time of the census; 6% of the urban and 2.4% of the total had toilet facilities.[5]

Geology

Overview

The East African Orogeny led to the growth of a mountain chain in the Precambrian (up to 800 million years ago or Ma), that was largely eroded afterwards.[6][7][8] Around 600 Ma, the Gondwana break-up led to the presence of tectonic structures and a Palaeozoic planation surface, that extents to the north and west of the Dogu'a Tembien massif.[9]

Subsequently, there was the deposition of sedimentary and volcanic formations, from older (at the foot of the massif) to younger, near the summits. From Palaeozoic to Triassic, Dogu’a Tembien was located near the South Pole. The (reactivate) Precambrian extensional faults guided the deposition of glacial sediments (Edaga Arbi Glacials and Enticho Sandstone). Later alluvial plain sediments were deposited (Adigrat Sandstone). The break-up of Gondwana (Late Palaeozoic to Early Triassic) led to an extensional tectonic phase, what caused the lowering of large parts of the Horn of Africa. As a consequence a marine transgression occurred, leading to the deposition of marine sediments (Antalo Limestone and Agula Shale).[10]

At the end of the Mesozoic tectonic phase, a new (Cretaceous) planation took place. After that, the deposition of continental sediments (Amba Aradam Formation) indicates the presence of less shallow seas, what was probably caused by a regional uplift. In the beginning of the Caenozoic, there was a relative tectonic quiescence, during which the Amba Aradam Sandstones were partially eroded what led to the formation of a new planation surface.[11]

In the Eocene, the Afar plume a broad regional uplift deformed the lithosphere, leading to the eruption of flood basalts. The magma followed pre-existing tectonic lineaments. A mere thickness of 400 metres of basalt indicates that the pre-trap rock topography was more elevated in Dogu'a Tembien as compared to more southerly areas. Three major formations may be distinguished: lower basalts, interbedded lacustrine deposits and upper basalts.[12] Almost at the same time, the Mekelle Dolerite intruded the Mesozoic sediments following joints and faults.[13]

A new magma intrusion occurred in the Early Miocene, what gave rise to a few phonolite plugs in Dogu’a Tembien.[12] The present geomorphology is marked by deep valleys, eroded as a result of the regional uplift. Throughout the Quaternary deposition of alluvium and freshwater tufa occurred in the valley bottoms.[14]

Fossils

In Dogu’a Tembien, there are two main fossil-bearing geological units. The Antalo Limestone (upper Jurassic) is the largest. Its marine deposits comprise mainly benthic marine invertebrates. Also, the Tertiary lacustrine deposits, interbedded in the basalt formations, contain a range of silicified mollusc fossils.[15]

In the Antalo Limestone: large Paracenoceratidae cephalopods (nautilus); Nerineidae indet.; sea urchins; Rhynchonellid brachiopod; crustaceans; coral colonies; crinoid stems.[16][15]

In the Tertiary silicified lacustrine deposits: Pila (gastropod); Lanistes sp.; Pirenella conica; and land snails (Achatinidae indet.).[15][17]

All snail shells, both fossil and recent, are called t’uyo in Tigrinya language, which means ‘helicoidal’.

Natural caves

The vast areas with outcropping Antalo Limestone hold numerous caves.

At Zeyi (13°33′N 39°9′E / 13.550°N 39.150°E), the monumental Zeyi Abune Aregawi church holds the entrance to Northern Ethiopia’s largest cave. The 364-metres long oval gallery displays stalactites, stalagmites, decametre-high columns, bell-holes following joints, and speleothems on walls and floor.[18]

The 145-metres long Zeleqwa horizontal gallery is located in a cliff nearby the river of the same name (13°38′N 39°7′E / 13.633°N 39.117°E). At the upper side of the cliff, there is an alignment of cavities: the “windows” of a gallery parallel to cliff and river. The cave floor holds with clay pots that would have served as food containers for villagers who went there hiding during an early 20th C. conflict.[19]

The Tinsehe caves, a cave system opening into the Upper Tsaliet River gorge near Addi Idaga (13°42′N 39°12′E / 13.700°N 39.200°E). The entrance near a small church is behind a waterfall 100 meters high.[20]

The May Hib’o cave (13°31′N 39°14′E / 13.517°N 39.233°E), a 70-metres long horizontal gallery, holds underground springs.[21]

Numerous other unexplored cave entrances are visible in Antalo Limestone cliffs.[19]

Rock-hewn churches

Like several other districts in Tigray, Dogu’a Tembien holds its share of rock-hewn or monolithic churches. These have literally been hewn from rock, mainly between the 10th and 14th centuries.[22][23][24]

The almost inaccessible Dabba Selama monastery (13°41.67′N 39°6.03′E / 13.69450°N 39.10050°E) is assumed to be the first monastery established in Ethiopia, by Saint Frumentius. The intrepid visitor will climb down, then scramble over narrow ledges along precipices, and finally climb an overhanging cliff. The mesa also comprises a church hewn in Adigrat Sandstone, in shape of a small basilica. The carvers attempted to establish four bays as wel as with a recess. The pillars are rounded (which is uncommon) and expand at either end, supporting arches that appear as triangles. Women are not allowed to do the ascent, nor to visit monastery or church. Independently from the difficult access to the monastery, the surrounding sandstone geomorphology is unique.[22][24]

The Amani’el church in May Baha (13°40′N 39°5.4′E / 13.667°N 39.0900°E) has also been carved in Adigrat Sandstone. Behind a pronaos (1960s), the rock church has cruciform columns, flat beams and a flat ceiling, a single arch, and a flat rear wall without apse. Windows give light to the church itself. Emperor Yohannes IV was baptised in this church.[22][24][25]

The Yohannes rock church at Debre Sema’it (13°34.62′N 39°2.24′E / 13.57700°N 39.03733°E) is located in the top of a rock pinnacle that overlooks Addi Nefas village. This church has also been hewn in Adigrat Sandstone.[25]

The Lafa Gebri’al rock church (13°35.87′N 39°17.25′E / 13.59783°N 39.28750°E) is now disused. It was hewn in a tufa plug. The church boosts a semi-circular wooden arch of approx. 1.5 metre across (in one piece).[25]

Ruba Bich’i’s village church (13°36′N 39°18′E / 13.600°N 39.300°E) is also an ancient rock-hewn church in freshwater tufa, and still in use.

The church of Kurkura Mika’el (13°40′N 39°9′E / 13.667°N 39.150°E), in a very scenic position in a small forest behind limestone pinnacles, is some 30 years old (File:Antalo_Limestone_at_Kurkura.jpg). Behind it, the remnant of the earlier church established in a natural cave of 20 metres by 20 metres. The roof of the cave is covered with sooth, evidencing the fact that the villagers took cover here, during the Italian bombardments of the Tembien battles in the mid-1930s.

The Kidane Mihret rock church at Ab’aro(13°44.5′N 39°12.06′E / 13.7417°N 39.20100°E), is surrounded by tufa plugs, springs and a cluster of trees. The church was established in widened caves of the tufa plug.[25]

Just outside the district, on the western slopes of the Dogu’a Tembien massif, there are seven other rock churches.

Mika’el Samba (13°42.56′N 39°6.81′E / 13.70933°N 39.11350°E) is a rock church hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. It holds grave cells off the main space. As Mika'el Samba is not a village church, priests are only present on the monthly Mika’els day, the twelfth day in the Ethiopian calendar.[22]

The Maryam Hibeto rock church (13°42.67′N 39°6.44′E / 13.71117°N 39.10733°E) is located at the edge of a church forest. It is hewn in Adigrat Sandstone, with a pronaos in front of it. On both sides of the main church, there are elongated chambers, maybe been the beginnings of an ambulatory. To enter the church, one has to go down a few. Remarkably, at the entrance, a pool of water is fed by a spring.[22]

The Welegesa church (13°43′N 39°4′E / 13.717°N 39.067°E) is hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. The entrance to the church is part of the rock, forming two courtyards, both hewn but not open at the upper side. The first courtyard holds graves; between the two, there is a block of stone with a cross in the window opening in its centre. The three-aisled church has a depth of four bays. There are entrances on both sides through hewn corridors. The church ceiling has a consistent height, holding cupolas, arches and capitals in each bay. The hewn tabot is in an apse. The sophisticated plan comprises a central axis and two open courtyards that cut deep into the rock.[22]

The newly hewn Medhanie Alem rock church in Mt. Werqamba (13°42.86′N 39°00.27′E / 13.71433°N 39.00450°E) is in a central, smaller peak (in Adigrat Sandstone).[25]

Northwest of Abiy Addi, the Geramba rock church (13°38.84′N 39°1.55′E / 13.64733°N 39.02583°E) is hewn in Tertiary silicified limestone, high up near the top to of the mountain. As a roof, a thin covering basalt layer was ingeniously used. The columns have a slightly cruciform plan and hold bracket capitals.[22]

Itsiwto Maryam rock church (13°40′N 39°1′E / 13.667°N 39.017°E) is hewn in Adigrat Sandstone. The church has a continuous hipped ceiling to the centre aisle. There are carved diagonal crosses as well as a cross carved above the arch into the sanctuary. The ceiling holds longitudinal beams that form a continuous lintel, which is similar to traditional Tigrayan workmanship. The church is at risk of collapse and hence access is not permitted.[22]

The Kidane Mihret rock church of Addi Nefas (13°33.3′N 39°1.44′E / 13.5550°N 39.02400°E) in Adigrat Sandstone is a rather primitive rock church, protected from the weather by a pronaos that surrounds the entrance. The church comprises two circular wel-carved cells that are used for baptisms. Above the sanctuary there is a series of small blind arcades. Beside the ancient church, a new cave is under excavation. Down from the church there are irrigated tropical gardens. Under cover trees, farmers grow coffee, local hops (gesho), and a few orange or lemon trees. Grivet monkeys are common an prevent growing of bananas.[22]

Traditional uses of rock

As Dogu'a Tembien holds a wide variety of rock types, there is expectedly a varied use of rock.

- Natural stone masonry. Preferentially, the easier shaped limestone and sandstone are used to build homesteads and churches, but particularly in the upland areas, basalt is also used. Traditionally, fermented mud will be used as mortar

- Fencing of homesteads, generally in dry stones

- Church bells, generally three elongated plates in phonolite or clinkstone, with different tonalities

- Milling stone: for this purpose plucked-bedrock pits, small rock-cut basins that naturally occur in rivers with kolks, are excavated from the river bed and further shaped. Milling is done at home using an elongated small boulder[26][27]

- Door and window lintels, prepared from rock types that frequently have an elongated shape (sandstone, phonolite, limestone), or that are easily shaped (tufa)

- In the 1930s, soldiers of the Italian army (2nd "28th October" Blackshirt Division) left a monumental inscription in Dogu'a Tembien, a metres-wide phonolite with inscriptions. It is located at the top of the Dabba Selama mountain, and was carved by soldiers that participated in the First Battle of Tembien[25]

- Troughs for livestock watering and feeding, generally hewn from tufa

- Footpath paving, generally done as community work. Some very ancient paved footpaths occur on major communication lines dating back to the period before the introduction of the automobile

- Heaped stones, in direct view of a church, where foot travellers stop, pray and put an additional stone

- Stones collected from farmlands in order to free space for the crop, and heaped in typical rounded metres-high heaps, called zala

- Contour bunding or gedeba: terrace walls in dry stone, typically laid out along the contour for sake of soil conservation

- Check dams or qetri in gullies for sake of gully erosion control

- Cobble stones, used for paving secondary streets in Hagere Selam. Generally limestone is used.

Hydrology

Rivers

Karstic resurgences

At the lower part of the Antalo Limestone, where it lays on the Adigrat Sandstone, there are high discharge resurgences that drain the karst aquifer. The large resurgence in Rubaksa (13°35′N 39°14′E / 13.583°N 39.233°E) irrigates an oasis in a dry limestone gorge. At Inda Mihtsun (13°33′N 39°21′E / 13.550°N 39.350°E), the May Bilbil resurgence is inside the bed of the Giba River; in the dry season spring water surges through the baseflow of the river. Also in Ferrey, on the slopes of the Tsaliet gorge, resurgences allow to irrigate gardens with tropical fruits.[28][29]

Environment

Vegetation

Wildlife

Large mammals

Large mammals of Dogu’a Tembien, with scientific (italics), English and Tigrinya language names.[30] - Cercopithecus aethiops; grivet monkey, ወዓግ (wi’ag) - Crocuta crocuta, spotted hyena, ዝብኢ (zibi) - Caracal caracal, caracal, ጭክ ኣንበሳ (ch’ok anbessa) - Panthera pardus, leopard, ነብሪ (nebri)[31] - Xerus rutilus, unstriped ground squirrel, ምጹጽላይ or ጨጨራ (mitsutsilay, chechera) - Canis mesomelas, black-backed jackal, ቡኳርያ (bukharya) - Canis anthus, golden jackal, ቡኳርያ (bukharya) - Papio hamadryas, hamadryas baboon, ጋውና (gawina) - Procavia capensis, rock hyrax, ጊሐ (gihè) - Felis silvestris, African wildcat, ሓክሊ ድሙ (hakili dummu) - Civettictis civetta, African civet, ዝባድ (zibad) - Papio anubis, olive baboon, ህበይ (hibey) - Ichneumia albicauda, white-tailed mongoose, ፂሒራ (tsihira) - Herpestes ichneumon, large grey mongoose, ፂሒራ (tsihira) - Hystrix cristata, crested porcupine, ቅንፈዝ (qinfiz) - Oreotragus oreotragus; klipspringer, ሰስሓ (sesiha) - Orycteropus afer, aardvark, ፍሒራ (fihira) - Genetta genetta, common genet, ስልሕልሖት (silihlihot) - Lepus capensis, cape hare, ማንቲለ (mantile) - Mellivora capensis, honey badger, ትትጊ (titigi)

Small rodents

The most common pest rodents with widespread distribution in agricultural fields and storage areas in Dogu’a Tembien (and in Tigray) are three Ethiopian endemic species: the Dembea grass rat (Arvicanthis dembeensis, sometimes considered a subspecies of Arvicanthis niloticus), Ethiopian white-footed rat (Stenocephalemys albipes), and Awash multimammate mouse (Mastomys awashensis). [32]

Bats

Bats occur in natural caves, church buildings and abandoned homesteads. The large colony of bats that roosts in Zeyi cave comprises Asellia tridens (trident leaf-nosed bat), Hipposideros caffer (Sundevall's leaf-nosed bat or Sundevall's roundleaf bat), and Rhinolophus blasii (Blasius's horseshoe bat).

Birds

With its numerous exclosures, forest fragments and church forests, Dogu’a Tembien is a birdwatcher’s paradise. Detailed inventories[33][34] list at least 170 bird species, including numerous endemic species.

Species belonging to the Afrotropical Highland Biome occur in the dry evergreen montane forests of the highland plateau but can also occupy other habitats. Wattled Ibis can be found feeding in wet grassland and open woodland. Black-winged Lovebird, Banded Barbet, Golden-mantled or Abyssinian Woodpecker, Montane White-eye, Rüppell's Robin-chat, Abyssinian Slaty Flycatcher and Tacazze Sunbird are found in evergreen forest, mountain woodlands and areas with scattered trees including fig trees, Euphorbia abyssinica and Juniperus procera. Erckel's francolin, Dusky Turtle Dove, Swainson's or Grey-headed Sparrow, Baglafecht Weaver, African Citril, Brown-rumped Seedeater and Streaky Seedeater are common Afrotropical breeding residents of woodland edges, scrubland and forest edges. White-billed Starling and Little Rock Thrush can be found on steep cliffs and White-collared Pigeon in gorges and rocky places but also in towns and villages.[33]

Species belonging to the Somali-Masai Biome. Hemprich's Hornbill and White-rumped Babbler are found in bushland, scrubland and dense secondary forest, often near cliffs, gorges or water. Chestnut-Winged or Somali Starling and Rüppell's Weaver are found in bushy and shrubby areas. Black-billed wood hoopoe has some red at the base of the bill or an entirely red bill in this area.[33]

Species belonging to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna Biome: Green-backed eremomela and Chestnut-crowned Sparrow-Weaver.[33]

Species that are neither endemic nor biome-restricted but that have restricted ranges or that can be more easily seen in Ethiopia than elsewhere in their range: Abyssinian Roller is an Ethiopian relative of Lilac-breasted Roller, which is an intra-tropical breeding migrant of south and east Africa, and of European Roller, an uncommon Palearctic passage migrant. Black-billed Barbet, Yellow-breasted Barbet and Grey-headed Batis are species from the Sahel and Northern Africa but also occur in Acacia woodlands in the area.[33]

The most regularly observed raptor birds in crop fields in Dogu’a Tembien are Augur buzzard (Buteo augur), Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo), Steppe Eagle (Aquila nipalensis), Lanner falcon (Falco biarmicus), Black kite (Milvus migrans), Yellow-billed kite (Milvus aegyptius) and Barn owl (Tyto alba).[35]

Birdwatching can be done particularly in exclosures and forests. Eighteen bird-watching sites have been inventoried[33] and mapped[36].

Agriculture

A sample enumeration performed by the CSA in 2001 interviewed 22,002 farmers in this woreda, who held an average of 0.79 hectares of land. Of the 17,387 hectares of private land surveyed, 91.06% was in cultivation, 0.55% pasture, 4.8% fallow, 0.13% woodland, and 2.99% was devoted to other uses. For the land under cultivation in this woreda, 77.88% was planted in cereals, 11.7% in pulses, and 1.36% in oilseeds; the area planted in vegetables is missing. Ten hectares were planted in fruit trees and eleven in gesho. 71.93% of the farmers both raised crops and livestock, while 28.07% only grew crops; the number who only raised livestock is missing. Land tenure in this woreda is distributed amongst 82.12% owning their land, 17.43% renting and 0.44 holding their land under other forms of tenure.[37]

History

Culture

Awrus

Tembien's frenetic Awrus dancing style[38][39]

The Siwa local beer culture

In almost every household of Dogu'a Tembien, the woman knows how to prepare the local beer, siwa. Ingredients are water, a home-baked and toasted flat bread commonly made from barley in the highlands,[40][41][42] and from sorghum, finger millet or maize in the lower areas,[43] some yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae),[44] and dried leaves of gesho (Rhamnus prinoides) that serve as a catalyser.[45] The brew is allowed to ferment for a few days, after which it is served, sometimes with the pieces of bread floating on it (the customer will gently blown them to one side of the beaker). The alcoholic content is 2% to 5%.[44] Most of the coarser part of the brew, the atella, remains back and is used as cattle feed.[46]

Siwa is consumed during social events, after (manual) work, and as an incentive for farmers and labourers. There are about a hundred traditional beer houses (Inda Siwa), often in unique settings, all across Dogu'a Tembien.

Surrounding woredas

References

- ^ Nyssen, J. and colleagues (2016). "Recovery of the historical aerial photographs of Ethiopia in the 1930s". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 17: 170–178. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2015.07.010.

- ^ a b Nyssen, J.; De Rudder, F.; Vlassenroot, K.; Fredu Nega; Azadi, Hossein (2019). Socio-demographic profile, food insecurity and food-aid based response. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Azadi, H.; De Rudder, F.; Vlassenroot, K.; Fredu Nega; Nyssen, J. (2017). "Targeting International Food Aid Programmes: The Case of Productive Safety Net Programme in Tigray, Ethiopia". Sustainability. 9 (10): 1716. doi:10.3390/su9101716.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Census 2007 Tables: Tigray Region Archived November 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.4, 2.5 and 3.4.

- ^ 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples' Region, Vol. 1, part 1 Archived November 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.12, 2.19, 3.5, 3.7, 6.3, 6.11, 6.13 (accessed 30 December 2008)

- ^ Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F. (2019). Regional geology of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Abbate, E; Bruni, P.; Sagri, M. (2015). Geology of Ethiopia: a review and geomorphological perspectives. In: Billi, P. (ed.), Landscapes and Landforms of Ethiopia. Springer Netherlands. pp. 33–64. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8026-1_2.

- ^ Swanson-Hysell, N.; Maloof, A.; Condon, D.; Jenkin, G.; Alene, M.; Tremblay, M.; Tesema, T.; Rooney, A.; Haileab, B. (2015). "Stratigraphy and geochronology of the Tambien Group, Ethiopia: Evidence for globally synchronous carbon isotope change in the Neoproterozoic". Geology. 43 (3): 323–326. doi:10.1130/G36347.1.

- ^ Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F.; Abebe, B. (2017). "Geology of the Tekeze River basin (Northern Ethiopia)". Journal of Maps. 13 (2): 621–631. doi:10.1080/17445647.2017.1351907.

- ^ Bosellini, A.; Russo, A.; Fantozzi, P.; Assefa, G.; Tadesse, S. (1997). "The Mesozoic succession of the Mekelle Outlier (Tigrai Province, Ethiopia)". Mem. Sci. Geol. 49: 95–116.

- ^ Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F.; Faccenna, C.; Abebe, B. (2017). "Erosion-tectonics feedbacks in shaping the landscape: An example from the Mekele Outlier (Tigray, Ethiopia)". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 129: 870–886. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.02.028.

- ^ a b Miruts Hagos; Kassa Amare; Koeberl, C.; Nyssen, J. (2019). The volcanic rock cover of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Nyssen, J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (eds), Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Tefera, M.; Chernet, T.; Haro, W. Geological Map of Ethiopia (1:2,000,000). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Institute of Geological Survey.

- ^ Moeyersons, J.; Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Deckers, J.; Mitiku Haile (2006). "Age and backfill/overfill stratigraphy of two tufa dams, Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia: Evidence for Late Pleistocene and Holocene wet conditions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 230 (1–2): 162–178.

- ^ a b c Lerouge, F.; Aerts, R. (2019). Fossil evidence of Dogu'a Tembien's environmental past. In: Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Kiessling, W.; Kumar, D.; Schemm-Gregory, M.; Mewis, H.; Aberhan, M (2011). "Marine benthic invertebrates from the Upper Jurassic of northern Ethiopia and their biogeographic affinities". J Afr Earth Sci. 59 (2–3): 195–214. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2010.10.006.

- ^ Merla, G.; Minucci, E. (1938). Missione geologica nel Tigrai. Rome (Italy): R. Accad. Ital.

- ^ Causer, D. (1962). "A cave in Ethiopia". Wessex Cave Club Journal. 7: 91–94.

- ^ a b Catlin, D; Largen, M; Monod, T; Morton, W (1973). "The caves of Ethiopia". Transactions of the Cave Research Group of Great Britain. 15: 107–168.

- ^ "Stalagmite sampling results table", Ethiopian Venture, First phase: Climate Reconstruction (accessed 17 May 2009)

- ^ Seifu Gebreselassie; Lanckriet, S. (2019). Local myths in relation to the natural environment of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sauter, R. (1976). "Eglises rupestres du Tigré". Annales d'Ethiopie. 10: 157–175. doi:10.3406/ethio.1976.1168.

- ^ Plant, R.; Buxton, D. (1970). "Rock-hewn churches of the Tigre province". Ethiopia Observer. 12 (3): 267.

- ^ a b c Gerster, G. (1972). Kirchen im Fels – Entdeckungen in Äthiopien. Zürich: Atlantis Verlag.

- ^ a b c d e f Nyssen, J. (2019). Description of trekking routes in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Nixon-Darcus, L.A. (2014). The cultural context of food grinding equipment in Northern Ethiopia: an ethnoarchaeological approach. PhD thesis. Canada: Simon Frazer University.

- ^ Gebre Teklu (2012). Ethnoarchaeological study of grind stones at Lakia’a in Adwa, Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia. PhD diss (PDF). Addis Ababa University.

- ^ Tesfaye Chernet; Gebretsadiq Eshete (1982). Hydrogeology of the Mekele area. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Mines and Energy.

- ^ Walraevens, K. and colleagues (2019). Hydrological context of water scarcity and storage on the mountain ridges in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-Trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains, the Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Aerts, Raf (2019). Forest and woodland vegetation in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Westerberg, M.; Craig, E.; Meheretu Yonas (2018). "First record of African leopard (Panthera pardus pardus L.) in semi‐arid area of Yechilay, northern Ethiopia". African Journal of Ecology. 56 (2): 375–377. doi:10.1111/aje.12436.

- ^ Meheretu Yonas; Kiros Welegerima; Sluydts, V; Bauer, H; Kindeya Gebrehiwot; Deckers, J; Makundi, R; Leirs, H (2015). "Reproduction and survival of rodents in crop fields: the effects of rainfall, crop stage and stone-bund density". Wildlife Research. 42 (2): 158–164. doi:10.1071/WR14121.

- ^ a b c d e f Aerts, R.; Lerouge, F.; November, E. (2019). Birds of forests and open woodlands in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Aerts, R; Lerouge, F; November, E; Lens, L; Hermy, M; Muys, B (2008). "Land rehabilitation and the conservation of birds in a degraded Afromontane landscape in northern Ethiopia". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17: 53–69. doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9230-2.

- ^ Meheretu Yonas; Leirs, H (2019). Raptor perch sites for biological control of agricultural pest rodents. In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Jacob, M.; Nyssen, J. (2019). Geo-trekking map of Dogu'a Tembien (1:50,000). In: Nyssen J., Jacob, M., Frankl, A. (Eds.). Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ "Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia. Agricultural Sample Survey (AgSE2001). Report on Area and Production - Tigray Region. Version 1.1 - December 2007" Archived November 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (accessed 26 January 2009)

- ^ Philip Briggs, Ethiopia: The Bradt Travel Guide, 3rd edition (Chalfont St Peters: Bradt, 2002), p. 270

- ^ Smidt, W. A Short History and Ethnography of the Tembien Tigrayans. Cham, Switzerland: SpringerNature. pp. 63–78.

- ^ Fetien Abay; Waters-Bayer, A.; Bjørnstad, Å. (2008). "Farmers' seed management and innovation in varietal selection: implications for barley breeding in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia". Ambio. 37 (4): 312–321.

- ^ Ayimut Kiros-Meles; Abang, M. (2008). "Farmers' knowledge of crop diseases and control strategies in the Regional State of Tigrai, northern Ethiopia: implications for farmer–researcher collaboration in disease management". Agriculture and Human Values.

- ^ Yemane Tsehaye; Bjørnstad, Å.; Fetien Abay (2012). "Phenotypic and genotypic variation in flowering time in Ethiopian barleys". Euphytica. 188 (3): 309–323.

- ^ Alemtsehay Tsegay; Berhanu Abrha; Getachew Hruy (2019). Major Crops and Cropping Systems in Dogu’a Tembien. Springer. pp. 403–413.

- ^ a b Lee, M.; Meron Regu; Semeneh Seleshe (2015). "Uniqueness of Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverage of plant origin, tella". Journal of Ethnic Foods. 2 (3): 110–114.

- ^ Abadi Berhane. "Gesho (Rhamnus prinoides) cultivation in Northern Ethiopia, Tigray" (PDF). Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Nyssen, J., and colleagues (2019). Cattle Breeds, Milk Production, and Transhumance in Dogu’a Tembien. Cham, Switzerland: SpringerNature. pp. 415–428.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)