History of longitude: Difference between revisions

→Longitude before the telescope: Adjusted size of map |

→Government Initiatives: Added details of the work of the Paris and Greenwich Observatories |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

In response to the problems of navigation, a number of European maritime powers offered prizes for a method to determine longitude at sea. Spain was the first, offering a reward for a solution in 1567, and this was increased to a permanent pension in 1598. Holland offered 30,000 florins in the early 17th-Century. Neither of these prizes produced a solution.<ref name="Siegel">{{cite journal |last1=Siegel |first1=Jonathan R. |title=Law and Longitude |journal=Tulane Law Review |date=2009 |volume=84 |pages=1-66}}</ref>{{rp|9}} |

In response to the problems of navigation, a number of European maritime powers offered prizes for a method to determine longitude at sea. Spain was the first, offering a reward for a solution in 1567, and this was increased to a permanent pension in 1598. Holland offered 30,000 florins in the early 17th-Century. Neither of these prizes produced a solution.<ref name="Siegel">{{cite journal |last1=Siegel |first1=Jonathan R. |title=Law and Longitude |journal=Tulane Law Review |date=2009 |volume=84 |pages=1-66}}</ref>{{rp|9}} |

||

[[File:Carte de France corrigé par ordre du Roy.jpg|thumb|Map of france presented to the Academy in 1684, showing the outline of a previous map (Sanson, light outline) compared to the new suurvey (heavier, shaded outline).]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The second half of the 17th century saw the foundation of two observatories, in Paris and London. The Paris Observatory was the first, being founded as an offshoot of the French Académie Des Sciences in 1667. The Observatory building, to the south of Paris, was completed in 1672.<ref name="Wolf 1902">{{cite book |last1=Wolf |first1=Charles |title=Histoire de l'Observatoire de Paris de sa fondation à 1793 |language=fr |date=1902 |publisher=Gauthier-Villars |location=Paris |url=https://archive.org/details/histoiredelobse00wolfgoog}}</ref> Early astronomers included [[Jean Picard]], [[Christiaan Huygens]], and [[Giovanni Domenico Cassini|Dominique Cassini]]<ref name="Wolf 1935">{{cite book |last1=Wolf |first1=A. |title=History Of Science, Technology And Philosophy: In The 16th And 17th Centuries Volume.1 |date=1935 |publisher=George Allen & Unwin |location=London}}</ref>{{rp|165-177}}. The Observatory was not set up for any specific project, but soon became involved in the survey of France that led (after many delays due to wars and unsympathetic ministries) to the Academy's first map of Paris in 1744. The survey used a combination of [[triangulation]] and astronomical observations, with the satellites of Jupiter used to determine longitude. By 1684, sufficient data had been obtained to show that previous maps of France had a major longitude error, showing the Atlantic coast too far to the west. In fact France was found to be substantially smaller than previously thought.<ref name="Gallois">{{cite journal |last1=Gallois |first1=L. |title=L'Académie des Sciences et les Origines de la Carte de Cassini: Premier article |journal=Annales De Géographie |date=1909 |volume=18 |issue=99 |pages=193-204 |jstor=23436957}}</ref><ref name="Picard 1729">{{cite journal |last1=Picard |first1=Jean |last2=de la Hire |first2=Philippe |title=Pour la Carte de France corrigée sur les Observations de MM. Picard & de la Hire |language=fr |journal=Mémoires De L' Académie Des Sciences |date=1729 |volume=7 |issue=7 |url=https://archive.org/details/picard-1729-mmoiresdelacad-07pari}}</ref> |

|||

The London observatory, at Greenwich, was set up a few years later, in 1675, and was established explicitly to address the longitude problem<ref name="Major">{{cite book |last1=Major |first1=F.G. |title=Quo Vadis: Evolution of Modern Navigation: The Rise of Quantum Techniques |date=2014 |publisher=Springer |location=New York |chapter=The Longitude Problem|pages=113-129 |doi=10.1007/978-1-4614-8672-5_6}}</ref>. [[John Flamsteed]], the first [[Astronomer Royal]] was instructed to "apply himself with the utmost care and diligence to the rectifying the tables of the motions of the heavens and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so-much-desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation"<ref name="Carpenter">{{cite journal |last1=Carpenter |first1=James |title=Greenwich Observatory |journal=The Popular Science Review |date=1872 |volume=11 |issue=42 |pages=267-282 |url=https://archive.org/details/carpenter-1872-popularsciencere-1118unse}}</ref>{{rp|268}}<ref name="Perryman">{{cite journal |last1=Perryman |first1=Michael |title=The history of astrometry |journal=The European Physical Journal H |date=2012 |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=745-792 |doi=10.1140/epjh/e2012-30039-4}}</ref>. The initial work was in catologuing stars and their position, and Flamsteed created a catalogue of 3,310 stars, which formed the basis for future work{{r|"Carpenter"|page=277}}. |

|||

| ⚫ | While Flamsteed's catalogue provided the basis for the lunar distance method, it did not in itself provide a solution. In 1714, the British Parliament passed “An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea”, and set up a Board to administer the award. The rewards depended on the accuracy of the method: from £10,000 for an accuracy within one degree of latitude (60 nautical miles at the equator) to £20,000 for accuracy within one-half of a degree.{{r|"Siegel"|p=9}} |

||

This prize in due course produced two workable solutions. The first was lunar distances, which required careful observation, accurate tables, and rather lengthy calculations. [[Nevil Maskelyne]],the newly appointed Astronomer Royal was on the Board of Longitude, started with Mayer's tables and after his own experiments at sea trying out the lunar distance method, proposed annual publication of pre-calculated lunar distance predictions in an official [[nautical almanac]] for the purpose of finding longitude at sea. Being very enthusiastic for the lunar distance method, Maskelyne and his team of [[human computer|computers]] worked feverishly through the year 1766, preparing tables for the new Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Published first with data for the year 1767, it included daily tables of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets and other astronomical data, as well as tables of lunar distances giving the distance of the Moon from the Sun and nine stars suitable for lunar observations (ten stars for the first few years).<ref name="HMNAO history">{{cite web |

This prize in due course produced two workable solutions. The first was lunar distances, which required careful observation, accurate tables, and rather lengthy calculations. [[Nevil Maskelyne]],the newly appointed Astronomer Royal was on the Board of Longitude, started with Mayer's tables and after his own experiments at sea trying out the lunar distance method, proposed annual publication of pre-calculated lunar distance predictions in an official [[nautical almanac]] for the purpose of finding longitude at sea. Being very enthusiastic for the lunar distance method, Maskelyne and his team of [[human computer|computers]] worked feverishly through the year 1766, preparing tables for the new Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Published first with data for the year 1767, it included daily tables of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets and other astronomical data, as well as tables of lunar distances giving the distance of the Moon from the Sun and nine stars suitable for lunar observations (ten stars for the first few years).<ref name="HMNAO history">{{cite web |

||

Revision as of 17:15, 4 July 2020

The history of longitude is a record of the effort, by astronomers, cartographers and navigators over several centuries, to discover a means of determining longitude.

The measurement of longitude is important to both cartography and navigation, in particular to provide safe ocean navigation. Knowledge of both latitude and longitude was required. Finding an accurate and reliable method of determining longitude took centuries of study, and involved some of the greatest scientific minds in human history.

Longitude before the telescope

Eratosthenes in the 3rd century BCE first proposed a system of latitude and longitude for a map of the world. His prime meridian (line of longitude) passed through Alexandria and Rhodes, while his parallels (lines of latitude) were not regularly spaced, but passed through known locations, often at the expense of being straight lines.[1] By the 2nd century BCE Hipparchus was using a systematic coordinate system, based on dividing the circle into 360°, to uniquely specify places on Earth.[2]: 31 So longitudes could be expressed as degrees east or west of the primary meridian, as we do today (though the primary meridian is different). He also proposed a method of determining longitude by comparing the local time of a lunar eclipse at two different places, to obtain the difference in longitude between them.[2]: 11 This method was not very accurate, given the limitations of the available clocks, and it was seldom done - possibly only once, using the Arbela eclipse of 330 BCE.[3] But the method is sound, and this is the first recognition that longitude can be determined by accurate knowledge of time.

Claudius Ptolemy, in the 2nd century CE, developed these ideas and geographic data into a mapping system. Until then, all maps had used a rectangular grid with latitude and longitude as straight lines intersecting at right angles.[4]: 543 [5]: 90 For large area this leads to unacceptable distortion, and for his map of the inhabited world, Ptolemy used projections (to use the modern term) with curved parallels that reduced the distortion. No maps (or manuscripts of his work) exist that are older than the 13th century, but in his Geography he gave detailed instructions and latitude and longitude coordinates for hundreds of locations that are sufficient to re-create the maps. While Ptolemy's system is well-founded, the actual data used are of very variable quality, leading to many inaccuracies and distortions.[6][4]: 551–553 [7] The most important of these is a systematic over-estimation of differences in longitude. Thus from Ptolemy's tables, the difference in Longitude between Gibraltar and Sidon is 59° 40', compared to the modern value of 40° 23', about 70% too high. Luccio (2013) has analysed these discrepancies, and concludes that much of the error arises from Ptolemy's use of a much smaller estimate of the size of the earth than that given by Eratosthenes - 500 stadia to the degree rather than 700 (though Eratosthenes would not have used degrees). Given the difficulties of astronomical measures of longitude in classical times, most if not all of Ptolemy's values would have been obtained from distance measures and converted to longitude using the 500 value. Eratosthenes' result is closer to the true value than Ptolemy's.[8]

Ancient Hindu astronomers were aware of the method of determining longitude from lunar eclipses, assuming a spherical earth. The method is described in the Sûrya Siddhânta, a Sanskrit treatise on Indian astronomy thought to date from the late 4th-century or early 5th-century CE.[9] Longitudes were referred to a prime meridian passing through Avantī, the modern Ujjain. Positions relative to this meridian were expressed in terms of length or time differences, but not in degrees, which were not used in India at this time. It is not clear whether this method was actually used in practice.

Islamic scholars knew the work of Ptolemy from at least the 9th-century CE, when the first translation of his Geography into Arabic was made. He was held in high regard, although his errors were known.[10] One of their developments was the construction of tables of geographical locations, with latitudes and longitudes, that added to the material provided by Ptolemy, and in some cases improved on it.[11] In most cases, the methods used to determine longitudes are not given, but there are a few accounts which give details. Simultaneous observations of two lunar eclipses at two locations were recorded by al-Battānī in 901, comparing Antakya with Raqqa. This allowed the difference in longitude between the two cities to be determined with an error of less than 1°. This is considered to be the best that can be achieved with the methods then available - observation of the eclipse with the naked eye, and determination of local time using an astrolabe to measure the altitude of a suitable "clock star".[12][13] Al-Bīrūnī, early in the 11th-century CE, also used eclipse data, but developed an alternative method involving an early form of triangulation. For two locations differing in both longitude and latitude, if the latitudes and the distance between them are known, as well as the size of the earth, it is possible to calculate the difference in longitude. With this method, al-Bīrūnī estimated the longitude difference between Baghdad and Ghazni using distance estimates from travellers over two different routes (and with a somewhat arbitrary adjustment for the crookedness of the roads). His result for the longitude difference between the two cities differs by about 1° from the modern value.[14] Mercier (1992) notes that this is a substantial improvement over Ptolemy, and that a comparable further improvement in accuracy would not occur until the 17th century in Europe[14]: 188 .

While knowledge of Ptolemy (and more generally of Greek science and philosophy) was growing in the Islamic world, it was declining in Europe. John Kirtland Wright's (1925) summary is bleak: "We may pass over the mathematical geography of the Christian period [in Europe] before 1100; no discoveries were made, nor were there any attempts to apply the results of older discoveries. [...] Ptolemy was forgotten and the labors of the Arabs in this field were as yet unknown".[15]: 65 Not all was lost or forgotten - Bede in his De naturum rerum affirms the sphericity of the earth. But his arguments are those of Aristotle, taken from Pliny. Bede adds nothing original.[16][17] There is more of note in the later medieval period. Wright (1923) cites a description by Walcher of Malvern of a lunar eclipse in Italy (October 19, 1094), which occurred shortly before dawn. On his return to England he compared notes with other monks to establish the time of their observation, which was before midnight. The comparison was too casual to allow a measurement of longitude differences, but the account shows that the principle was still understood.[18]: 81 In the 12th Century, astronomical tables were prepared for a number of European cities, based on the work of al-Zarqālī in Toledo. These had to be adapted to the meridian of each city, and it is recorded that the lunar eclipse of September 12, 1178 was used to establish the longitude differences between Toledo, Marseilles, and Hereford[18]: 85 . The Hereford tables also added a list of over 70 locations, many in the Islamic world, with their longitudes and latitudes. These represent a great improvement on the similar tabulations of Ptolemy. For example, the longitudes of Ceuta and Tyre are given as 8° and 57° (east of the meridian of the Canary Islands), a difference of 49°, compared to the modern value of 40.5°, an overestimate of less than 20%.[18]: 87–88 In general, the later medieval period is marked by an increase in interest in geography, and of a willingness to make observations, stimulated both by an increase in travel (including pilgrimage and the Crusades) and the availability of Islamic sources from contact with Spain and North Africa[19][20] At the end of the medieval period, Ptolemy's work became directly available with the translations made in Florence at the end of the 14th- and beginning of the 15th-centuries.[21]

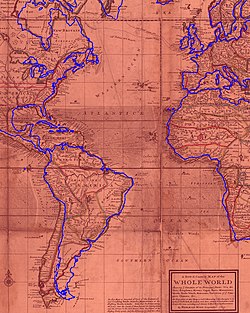

The 15th and 16th Centuries were the time of Portuguese and Spanish voyages of discovery and conquest. In particular the arrival of Europeans in the New World led to questions of where they actually were. Christopher Columbus made two attempts to use lunar eclipses to discover his longitude, the first in Saona Island, now in the Dominican Republic, on 14 September 1494 (during his second voyage), and the second on the north coast of Jamaica on 29 February 1504 (during his fourth voyage). He was unable to compare his observations with ones in Europe, and it is assumed that he used astronomical tables for reference. In any case his determinations of latitude showed large errors of 13 and 38° W respectively.[22] Randles (1985) documents longitude measurement by the Portuguese and Spanish between 1514 and 1627 both in the Americas and Asia. Errors ranged from 2-25°.[23]

Telescopes and Clocks

In 1608 a patent was submitted to the government in the Netherlands for a refracting telescope. The idea was picked up by, among others Galileo who made his first telescope the following year, and began his series of astronomical discoveries that included the satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, and the resolution of the Milky Way into individual stars. Over the next half century improvements in optics and the use of calibrated mountings, optical grids, and micrometers to adjust positions transformed the telescope from an observation device to an accurate measurement tool.[25][26][27][28] It also greatly increased the range of events that could be observed to determine longitude.

The second important technical development for longitude determination was the pendulum clock, patented by Christiaan Huygens in 1657.[29] This gave an increase in accuracy of about 30 fold over previous mechanical clocks - the best pendulum clocks were accurate to about 10 seconds per day.[30] From the start, Huygens intended his clocks to be used for determination of longitude at sea.[31][32] However, pendulum clocks did not tolerate the motion of a ship sufficiently well, and after a series of trials it was concluded that other approaches would be needed. The future of pendulum clocks would be on land. Together with telescopic instruments, they would revolutionize observational astronomy and cartography in the coming years.[33]

Methods of determining longitude

The development of the telescope and accurate clocks increased the range of methods that could be used to determine longitude. With one exception (magnetic declination) they all depend on a common principle, which was to determine an absolute time from an event or measurement and to compare the corresponding local time at two different locations. (Absolute here refers to a time that is the same for an observer anywhere on earth.) Each hour of difference of local time corresponds to a 15 degrees change of longitude (360 degrees divided by 24 hours). Local noon is defined as the time at which the sun is at the highest point in the sky. This is hard to determine directly, as the apparent motion of the sun is nearly horizontal at noon. The usual approach was to take the mid-point between two times at which the sun was at the same altitude. With an unobstructed horizon, the mid-point between sunrise and sunset could be used.[34]

To determine the measure of absolute time, lunar eclipses continued to be used. Other proposed methods include the following

Lunar Distances

This is the earliest proposal having been first suggested in a letter by Amerigo Vespucci referring to observations he made in 1499[35]. The method was published by Johannes Werner in 1514[36], and discussed in detail by Petrus Apianus in 1524[37]. The method depends on the motion of the moon relative to the "fixed" stars, which completes a 360° circuit in 27.3 days on average (a lunar month), giving an observed movement of just over 0.5°/hour. Thus an accurate measurement of the angle is required, since a 2' of arc (1/30°) difference in the angle between the moon and the selected star corresponds to a 1° difference in the longitude - 60 nautical miles at the equator[38]. The method also required accurate tables, which were complex to construct, since they had to take into account parallax and the various sources of irregularity in the orbit of the moon. Neither measuring instruments nor astronomical tables were accurate enough in the early 16th-century. Vespucci's attempt to use the method placed him at 82° east of Cadiz, when he was actually less than 40° east of Cadiz, on the north coast of Brazil[35].

Satellites of Jupiter

In 1612, having determined the orbital periods of Jupiter's four brightest satellites (Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto), Galileo proposed that with sufficiently accurate knowledge of their orbits one could use their positions as a universal clock, which would make possible the determination of longitude. He worked on this problem from time to time during the remainder of his life.

The method required a telescope, as the moons are not visible to the naked eye. For use in marine navigation, Galileo proposed the celatone, a device in the form of a helmet with a telescope mounted so as to accommodate the motion of the observer on the ship.[39] This was later replaced with the idea of a pair of nested hemispheric shells separated by a bath of oil. This would provide a platform that would allow the observer to remain stationary as the ship rolled beneath him, in the manner of a gimballed platform. To provide for the determination of time from the observed moons' positions, a Jovilabe was offered — this was an analogue computer that calculated time from the positions and that got its name from its similarities to an astrolabe.[40] The practical problems were severe and the method was never used at sea.

On land, this method proved useful and accurate. An early example was the measurement of the longitude of the site of Tycho Brahe's former observatory on the Island of Hven. Jean Picard on Hven and Cassini in Paris made observations during 1671 and 1672, and obtained a value of 42 minutes 10 seconds (time) east of Paris, corresponding to 10° 32' 30", about 12' (1/5°) of arc higher than the modern value.[41]

Appulses and Occultations

Two proposed methods depend on the relative motions of the moon and a star or planet. An appulse is the least apparent distance between the two objects, an occultation occurs when the star or planet passes behind the moon -- essentially a type of eclipse. The times of either of these events can be used as the measure of absolute time in the same way as with a lunar eclipse. Edmond Halley described the use of this method to determine the longitude of Balasore, using observations of the star Aldebaran (the Bull's Eye) in 1680, with an error of just over half a degree[42]. He published a more detailed account of the method in 1717[43]. A longitude determination using the occultation of a planet, Jupiter, was described by James Pound in 1714[44].

Chronometers

The first to suggest travelling with a clock to determine longitude, in 1530, was Gemma Frisius, a physician, mathematician, cartographer, philosopher, and instrument maker from the Netherlands. The clock would be set to the local time of a starting point whose longitude was known, and the longitude of any other place could be determined by comparing its local time with the clock time.[45][46]: 259 While the method is perfectly sound, and was partly stimulated by recent improvements in the accuracy of mechanical clocks, it still requires far more accurate time-keeping than was available in Frisius's day. The term chronometer was not used until the following century[47], and it would be over two centuries before this became the standard method for determining longitude at sea[48].

Magnetic Declination

This method is based on the observation that a compass needle does not in general point exactly north. The angle between true north and the direction of the compass needle (magnetic north) is called the magnetic declination or variation, and its value varies from place to place. Several writers proposed that the size of magnetic declination could be used to determine longitude. Mercator suggested that the magnetic north pole was an island in the longitude of the Azores, where magnetic declination was, at that time, close to zero. These ideas were supported by Michiel Coignet in his Nautical Instruction[46].

Halley made extensive studies of magnetic variation during his voyages on the pink Paramour. He published the first chart showing isogonic lines - lines of equal magnetic declination - in 1701[49]. One of the purposes of the chart was to aid in determining longitude, but the method was eventually to fail as changes in magnetic declination over time proved too large and too unreliable to provide a basis for navigation.

Land and Sea

Measurements of longitude on land and sea complemented one another. As Edmond Halley pointed out in 1717, "But since it would be needless to enquire exactly what longitude a ship is in, when that of the port to which she is bound is still unknown it were to be wisht that the princes of the earth would cause such observations to be made, in the ports and on the principal head-lands of their dominions, each for his own, as might once for all settle truly the limits of the land and sea."[43] But determinations of longitude on land and sea did not develop in parallel.

On land, the period from the development of telescopes and pendulum clocks until the mid 18th-Century saw a steady increase in the number of places whose longitude had been determined with reasonable accuracy, often with errors of less than a degree, and nearly always within 2-3°. By the 1720s errors were consistently less than 1°[50].

At sea during the same period, the situation was very different. Two problems proved intractable. The first was the need for immediate results. On land, an astronomer at, say, Cambridge Massachusetts could wait for the next lunar eclipse that would be visible both at Cambridge and in London; set a pendulum clock to local time in the few days before the eclipse; time the events of the eclipse; send the details across the Atlantic and wait weeks or months to compare the results with a London colleague who had made similar observations; calculate the longitude of Cambridge; then send the results for publication, which might be a year or two after the eclipse[51]. And if either Cambridge or London had no visibility because of cloud, wait for the next eclipse. The marine navigator needed the results quickly. The second problem was the marine environment. Making accurate observations in an ocean swell is much harder than on land, and pendulum clocks do not work well in these conditions. Thus longitude at sea could only be estimated from dead reckoning (DR) - by using estimations of speed and course from a known starting position - at a time when longitude determination on land was becoming increasingly accurate.

In order to avoid problems with not knowing one's position accurately, navigators have, where possible, relied on taking advantage of their knowledge of latitude. They would sail to the latitude of their destination, turn toward their destination and follow a line of constant latitude. This was known as running down a westing (if westbound, easting otherwise).[52] This prevented a ship from taking the most direct route (a great circle) or a route with the most favourable winds and currents, extending the voyage by days or even weeks. This increased the likelihood of short rations,[53] which could lead to poor health or even death for members of the crew due to scurvy or starvation, with resultant risk to the ship.

A famous longitude error that had disastrous consequences occurred in April 1741. George Anson, commanding H.M.S. Centurion, was rounding Cape Horn from east to west. Believing himself past the Cape, he headed north, only to find the land straight ahead. A particularly strong easterly current had put him well to the east of his DR position, and he had to resume his westerly course for several days. When finally past the Horn, he headed north for Juan Fernandez, to take on supplies, and to relieve his crew, many of whom were sick with scurvy. On reaching the latitude of Juan Fernandez, he did not know whether the Island was to the east or West, and spent 10 days sailing first eastwards and then westwards before finally reaching the island. During this time over half of the ship's company died of scurvy[54].

Government Initiatives

In response to the problems of navigation, a number of European maritime powers offered prizes for a method to determine longitude at sea. Spain was the first, offering a reward for a solution in 1567, and this was increased to a permanent pension in 1598. Holland offered 30,000 florins in the early 17th-Century. Neither of these prizes produced a solution.[55]: 9

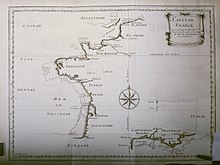

The second half of the 17th century saw the foundation of two observatories, in Paris and London. The Paris Observatory was the first, being founded as an offshoot of the French Académie Des Sciences in 1667. The Observatory building, to the south of Paris, was completed in 1672.[56] Early astronomers included Jean Picard, Christiaan Huygens, and Dominique Cassini[57]: 165–177 . The Observatory was not set up for any specific project, but soon became involved in the survey of France that led (after many delays due to wars and unsympathetic ministries) to the Academy's first map of Paris in 1744. The survey used a combination of triangulation and astronomical observations, with the satellites of Jupiter used to determine longitude. By 1684, sufficient data had been obtained to show that previous maps of France had a major longitude error, showing the Atlantic coast too far to the west. In fact France was found to be substantially smaller than previously thought.[58][59]

The London observatory, at Greenwich, was set up a few years later, in 1675, and was established explicitly to address the longitude problem[60]. John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal was instructed to "apply himself with the utmost care and diligence to the rectifying the tables of the motions of the heavens and the places of the fixed stars, so as to find out the so-much-desired longitude of places for the perfecting the art of navigation"[61]: 268 [28]. The initial work was in catologuing stars and their position, and Flamsteed created a catalogue of 3,310 stars, which formed the basis for future work[61]: 277 .

While Flamsteed's catalogue provided the basis for the lunar distance method, it did not in itself provide a solution. In 1714, the British Parliament passed “An Act for providing a publick Reward for such Person or Persons as shall discover the Longitude at Sea”, and set up a Board to administer the award. The rewards depended on the accuracy of the method: from £10,000 for an accuracy within one degree of latitude (60 nautical miles at the equator) to £20,000 for accuracy within one-half of a degree.[55]: 9

This prize in due course produced two workable solutions. The first was lunar distances, which required careful observation, accurate tables, and rather lengthy calculations. Nevil Maskelyne,the newly appointed Astronomer Royal was on the Board of Longitude, started with Mayer's tables and after his own experiments at sea trying out the lunar distance method, proposed annual publication of pre-calculated lunar distance predictions in an official nautical almanac for the purpose of finding longitude at sea. Being very enthusiastic for the lunar distance method, Maskelyne and his team of computers worked feverishly through the year 1766, preparing tables for the new Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris. Published first with data for the year 1767, it included daily tables of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets and other astronomical data, as well as tables of lunar distances giving the distance of the Moon from the Sun and nine stars suitable for lunar observations (ten stars for the first few years).[62] [63] This publication later became the standard almanac for mariners worldwide. Since it was based on the Royal Observatory, it helped lead to the international adoption a century later of the Greenwich Meridian as an international standard.

The second method was the use of chronometer. Many, including Isaac Newton, were pessimistic that a clock of the required accuracy could ever be developed. Half a degree of longitude is equivalent to two minutes of time, so the required accuracy is a few seconds a day. At that time, there were no clocks that could come close to maintaining such accurate time while being subjected to the conditions of a moving ship. John Harrison, a Yorkshire carpenter and clock-maker believed it could be done, and spent over three decades proving it.[55]: 14–27

Harrison built five chronometers, two of which were tested at sea. His first, H-1, was not tested under the conditions that were required by the Board of Longitude. Instead, the Admiralty required that it travel to Lisbon and back. It lost considerable time on the outward voyage but performed excellently on the return leg, which was not part of the official trial. The perfectionist in Harrison prevented him from sending it on the required trial to the West Indies (and in any case it was regarded as too large and impractical for service use). He instead embarked on the construction of H-2. This chronometer never went to sea, and was immediately followed by H-3. During construction of H-3, Harrison realised that the loss of time of the H-1 on the Lisbon outward voyage was due to the mechanism losing time every time the ship came about while tacking down the English Channel. Harrison produced H-4, with a completely different mechanism which did get its sea trial and satisfied all the requirements for the Longitude Prize. However, he was not awarded the prize and was forced to fight for his reward.

A French expedition under Le Tellier performed the first measurement of longitude using marine chronometers aboard Aurore in 1767.[64]

Though the British Parliament rewarded John Harrison for his marine chronometer in 1773, his chronometers were not to become standard. Chronometers such as those by Thomas Earnshaw were suitable for general nautical use by the middle of the 19th century (1836).[65] However, they remained very expensive and the lunar distance method continued to be used for some decades.

Lunars or chronometers?

The lunar distance method was initially labour-intensive because of the time-consuming complexity of the calculations for the Moon's position. Early trials of the method could involve four hours of effort.[66] However, the publication of the Nautical Almanac starting in 1767 provided tables of pre-calculated distances of the Moon from various celestial objects at three-hour intervals for every day of the year, making the process practical by reducing the time for calculations to less than 30 minutes and as little as ten minutes with some efficient tabular methods.[67] Lunar distances were widely used at sea from 1767 to about 1905. With the new tables with Haversines from Josef de Mendoza y Ríos (1805), computation time was reduced to a few minutes.

Between 1800 and 1850 (earlier in British and French navigation practice, later in American, Russian, and other maritime countries), affordable, reliable marine chronometers became available, with a trend to replace the method of lunars as soon as they could reach the market in large numbers. It became possible to buy three or more chronometers, serving for checking on each other (redundancy), although according to Nathaniel Bowditch, their use was precluded because they were very expensive, [68] obviously much higher than a single sextant of sufficient quality for lunar distance navigation which continued in use until 1906.[69]

Two chronometers provided dual modular redundancy, allowing a backup if one should cease to work, but not allowing any error correction if the two displayed a different time, since in case of contradiction between the two chronometers, it would be impossible to know which one was wrong (the error detection obtained would be the same of having only one chronometer and checking it periodically: every day at noon against dead reckoning). Three chronometers provided triple modular redundancy, allowing error correction if one of the three was wrong, so the pilot would take the average of the two with closer readings (average precision vote). There is an old adage to this effect, stating: "Never go to sea with two chronometers; take one or three."[70] At one time this observation or rule was an expensive one as the cost of three sufficiently accurate chronometers was more than the cost of many types of smaller merchant vessels.[71] Some vessels carried more than three chronometers – for example, HMS Beagle carried 22 chronometers.[72]

By 1850, the vast majority of ocean-going navigators worldwide had ceased using the method of lunar distances. Nonetheless, expert navigators continued to learn lunars as late as 1905, though for most this was a textbook exercise since they were a requirement for certain licenses. They also continued in use in land exploration and mapping where chronometers could not be kept secure in harsh conditions. The British Nautical Almanac published lunar distance tables until 1906 and the instructions until 1924.[73] Such tables last appeared in the 1912 USNO Nautical Almanac, though an appendix explaining how to generate single values of lunar distances was published as late as the early 1930s.[63] The presence of lunar distance tables in these publications until the early 20th century does not imply common usage until that time period but was simply a necessity due to a few remaining (soon to be obsolete) licensing requirements. The development of wireless telegraph time signals in the early 20th century, used in combination with marine chronometers, put a final end to the use of lunar distance tables.

Modern solutions

Telegraph signals were used regularly for time coordination by the United States Naval Observatory starting in 1865.[74] These were used, for example, by astronomers during the Solar eclipse of July 29, 1878 to calibrate the longitude of their observations.[75]

Time signals were first broadcast by wireless telegraphy in 1904, by the US Navy from Navy Yard in Boston. Another regular broadcast began in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1907, and time signals that became more widely used were broadcast from the Eiffel Tower starting in 1910.[76] As ships adopted radio telegraph sets for communication, such time signals were used to correct chronometers. This method drastically reduced the importance of lunars as a means of verifying chronometers.

Modern sailors have a number of choices for determining accurate positional information, including radar and the Global Positioning System, commonly known as GPS, a satellite navigation system. With technical refinements that make position fixes accurate to within meters, the radio-based LORAN system was used in the late 20th century but has been discontinued in North America. Combining independent methods is used as a way to improve the accuracy of position fixes. Even with the availability of multiple modern methods of determining longitude, a marine chronometer and sextant are routinely carried as a backup system.[citation needed]

Further refinements for longitude on land

For the determination of longitude on land, the preferred method became exchanges of chronometers between observatories to accurately determine the differences in local times in conjunction with observation of the transit of stars across the meridian.

An alternative method was the simultaneous observation of occultations of stars at different observatories. Since the event occurred at a known time, it provided an accurate means of determining longitude. In some cases, special expeditions were mounted to observe a special occultation or eclipse to determine the longitude of a location without a permanent observatory.

From the mid-19th century, telegraph signalling allowed more precisely synchronization of star observations. This significantly improved longitude measurement accuracy. The Royal Observatory in Greenwich and the U.S. Coast Survey coordinated European and North American longitude measurement campaigns in the 1850s and 1860s, resulting in improved map accuracy and navigation safety. Synchronization by radio followed in the early 20th century. In the 1970s, the use of satellites was developed to more precisely measure geographic coordinates (GPS).

Notable scientific contributions

In the process of searching for a solution to the problem of determining longitude, many scientists added to the knowledge of astronomy and physics.

- Galileo - detailed studies of Jupiter's moons, which proved Ptolemy's assertion that not all celestial objects orbit the Earth

- Robert Hooke - determination of the relationship between forces and displacements in springs, laying the foundations for the theory of elasticity.

- Christiaan Huygens - invention of pendulum clock and a spring balance for pocket watch.

- Jacob Bernoulli, with refinements by Leonhard Euler - invention of the calculus of variations for Bernoulli's solution of the brachistochrone problem (finding the shape of the path of a pendulum with a period that does not vary with degree of lateral displacement). This refinement created greater accuracy in pendulum clocks.

- John Flamsteed and many others - formalization of observational astronomy by means of astronomical observatory facilities, further advancing modern astronomy as a science.

- John Harrison - invention of the gridiron pendulum and bimetallic strip along with further studies in the thermal behavior of materials. This contributed to the evolving science of solid mechanics. His invention of caged roller bearings contributed to refinements in mechanical engineering designs.

See also

References

- ^ Roller, Duane W. (2010). Eratosthenes' Geography. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b Dicks, D.R. (1953). Hipparchus : a critical edition of the extant material for his life and works (PhD). Birkbeck College, University of London.

- ^ Hoffman, Susanne M. (2016). "How time served to measure the geographical position since Hellenism". In Arias, Elisa Felicitas; Combrinck, Ludwig; Gabor, Pavel; Hohenkerk, Catherine; Seidelmann, P.Kenneth (eds.). The Science of Time. Astrophysics and Space Science Proceedings. Springer International. pp. 25–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59909-0_4.

- ^ a b Bunbury, E.H. (1879). A History of Ancient Geography. Vol. 2. London: John Murray.

- ^ Snyder, John P (1987). Map Projections - A working manual. Washington DC: US Geoliogical Survey.

- ^ Mittenhuber, Florian (2010). "The Tradition of Texts and Maps in Ptolemy's Geography". In Jones, Alexander (ed.). Ptolemy in Perspective: Use and Criticism of his Work from Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 95-119. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2788-7_4.

- ^ Shcheglov, Dmitry A. (2016). "The Error in Longitude in Ptolemy's Geography Revisited". The Cartographic Journal. 53 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1179/1743277414Y.0000000098.

- ^ Russo, Lucio (2013). "Ptolemy's longitudes and Eratosthenes' measurement of the earth's circumference". Mathematics and Mechanics of Complex Systems. 1 (1): 67–79. doi:10.2140/memocs.2013.1.67.

- ^ Burgess, Ebenezer (1935). Translation of the Surya Siddhanta a text-book of Hindu astronomy with notes and appendix. University of Calcutta. pp. 45–48.

- ^ Ragep, F.Jamil (2010). "Islamic reactions to Ptolemy's imprecisions". In Jones, A. (ed.). Ptolemy in Perspective. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2788-7. ISBN 978-90-481-2788-7.

- ^ Tibbetts, Gerald R. (1992). "The Beginnings of a Cartographic Tradition". In Harley, J.B.; Woodward, David (eds.). The History of Cartography Vol. 2 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies. University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Said, S.S.; Stevenson, F.R. (1997). "Solar and Lunar Eclipse Measurements by Medieval Muslim Astronomers, II: Observations". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 28 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1177/002182869702800103.

- ^ Steele, John Michael (1998). Observations and predictions of eclipse times by astronomers in the pre-telescopic period (PhD). University of Durham (United Kingdom).

- ^ a b Mercier, Raymond P. (1992). "Geodesy". In Harley, J.B.; Woodward, David (eds.). The History of Cartography Vol. 2 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies. University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Wright, John Kirtland (1925). The geographical lore of the time of the Crusades: A study in the history of medieval science and tradition in Western Europe. New York: American geographical society.

- ^ Darby, H.C. (1935). "The geographical ideas of the Venerable Bede". Scottish Geographical Magazine. 51 (2): 84–89. doi:10.1080/00369223508734963.

- ^ Friedman, John Block (2000). Trade, Travel and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis Ltd. p. 495. ISBN 0-8153-2003-5.

- ^ a b c Wright, John Kirtland (1923). "Notes on the Knowledge of Latitudes and Longitudes in the Middle Ages". Isis. 5 (1).

- ^ Beazley, C.Raymond (1901). The Dawn of Modern Geography, vol. I, London, 1897; A History of Exploration and Geographical Science from the Close of the Ninth to the Middle of the Thirteenth Century (c. AD 900-1260). London: John Murray.

- ^ Lilley, Keith D. (2011). "Geography's medieval history: A neglected enterprise?". Dialogues in Human Geography. 1 (2): 147–162. doi:10.1177/2043820611404459.

- ^ Gautier Dalché, P. (2007). "The reception of Ptolemy's Geography (end of the fourteenth to beginning of the sixteenth century)". In Woodward, D. (ed.). The History of Cartography, Volume 3. Cartography in the European Renaissance, Part 1 (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 285–364.

- ^ Pickering, Keith (1996). "Columbus's Method of Determining Longitude: An Analytical View". The Journal of Navigation. 49 (1): 96–111. doi:10.1017/S037346330001314X.

- ^ Randles, W.G.L. (1985). "Portuguese and Spanish attempts to measure longitude in the 16th century". Vistas in Astronomy. 28: 235–241.

- ^ Chapman, Allan (1976). "Astronomia practica: The principal instruments and their uses at the Royal Observatory". Vistas in Astronomy. 20: 141–156. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(76)90025-8.

- ^ Pannekoek, Anton (1989). A history of astronomy. Courier Corporation. pp. 259–276.

- ^ Van Helden, Albert (1974). "The Telescope in the Seventeenth Century". Isis. 65 (1): 38–58.

- ^ Høg, Erik (2009). "400 years of astrometry: from Tycho Brahe to Hipparcos". Experimental Astronomy. 25 (1): 225–240. doi:10.1007/s10686-009-9156-7.

- ^ a b Perryman, Michael (2012). "The history of astrometry". The European Physical Journal H. 37 (5): 745–792. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2012-30039-4. Cite error: The named reference "Perryman" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Grimbergen, Kees (2004). Fletcher, Karen (ed.). Huygens and the advancement of time measurements. Titan - From Discovery to Encounter. ESTEC, Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. pp. 91–102. ISBN 92-9092-997-9.

- ^ Blumenthal, Aaron S.; Nosonovsky, Michael (2020). "Friction and Dynamics of Verge and Foliot: How the Invention of the Pendulum Made Clocks Much More Accurate". Applied Mechanics. 1 (2): 111–122. doi:10.3390/applmech1020008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Huygens, Christiaan (1669). "Instructions concerning the use of pendulum-watches for finding the longitude at sea". Philosophical Transactions. 4 (47): 937–953.

- ^ Howard, Nicole (2008). "Marketing Longitude: Clocks, Kings, Courtiers, and Christiaan Huygens". Book History. 11: 59–88.

- ^ Olmsted, J.W. (1960). "The Voyage of Jean Richer to Acadia in 1670: A Study in the Relations of Science and Navigation under Colbert". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 104 (6): 612–634.

- ^ Norie, John William (1805). A New and Complete Epitome of Practical Navigation. William Heather: William Heather. p. 219.

- ^ a b Cited in: Arciniegas, German (1955). Amerigo And The New World The Life & Times Of Amerigo Vespucci. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 192.

- ^ Werner, Johann (1514). In hoc opere haec continentur Noua translatio primi libri Geographiae Cl. Ptolomaei (in Latin). Nurembergae: Ioanne Stuchs.

- ^ Apianus, Petrus (1533). Cosmographicus liber Petri Apiani mathematici, iam denuo integritati restitutus per Gemmam Phrysium (in Latin). Landshut: vaeneunt in pingui gallina per Arnoldum Birckman.

- ^ Halley, Edmund (1731). "A Proposal of a Method for Finding the Longitude at Sea within a Degree, or Twenty Leagues". Philosophical Transactions. 37 (417–426): 185–195.

- ^ Celatone

- ^ Jovilabe

- ^ Picard, Jean (1729). "Voyage D'Uranibourg ou Observations Astronomiques faites en Dannemarck". Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences (in French). 7 (1): 223–264.

- ^ Halley, Edmund (1682). "An account of some very considerable observations made at Ballasore in India, serving to find the longitude of that place, and rectifying very great errours in some famous modern geographers". Philosophical Collections of the Royal Society of London. 5 (1): 124–126. doi:10.1098/rscl.1682.0012.

- ^ a b Halley, Edmund (1717). "An advertisement to astronomers, of the advantages that may accrue from the observation of the moon's frequent appulses to the Hyades, during the next three ensuing years". Philosophical Transactions. 30 (354): 692–694. Cite error: The named reference "Halley 1717" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Pound, James (1714). "Some late curious astronomical observations communicated by the Reverend and learned Mr. James Pound, Rector of Wansted". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 29 (347): 401–405.

- ^ Pogo, A (1935). "Gemma Frisius, His Method of Determining Differences of Longitude by Transporting Timepieces (1530), and His Treatise on Triangulation (1533)". Isis. 22 (2): 469–506. doi:10.1086/346920.

- ^ a b Meskens, Ad (1992). "Michiel Coignet's Nautical Instruction". The Mariner's Mirror. 78 (3): 257–276. doi:10.1080/00253359.1992.10656406.

- ^ Koberer, Wolfgang (2016). "On the First Use of the Term "Chronometer"". The Mariner's Mirror. 102 (2): 203–206. doi:10.1080/00253359.2016.1167400.

- ^ Gould, Rupert T (1921). "The History of the Chronometer". The Geographical Journal. 57 (4): 253–268. JSTOR 1780557.

- ^ Halley, Edm. (1701). A New and Correct Chart Shewing the Variations of the Compass in the Western & Southern Oceans as Observed in ye Year 1700 by his Ma[jes]ties Command. London: Mount and Page.

- ^ See, for example, Port Royal, Jamaica: Halley, Edmond (1722). "Observations on the Eclipse of the Moon, June 18, 1722. and the Longitude of Port Royal in Jamaica". Philosophical Transactions. 32 (370–380): 235–236.; Buenos Aires: Halley, Edm. (1722). "The Longitude of Buenos Aires, Determin'd from an Observation Made There by Père Feuillée". Philosophical Transactions. 32 (370–380): 2–4.Santa Catarina, Brazil: Legge, Edward; Atwell, Joseph (1743). "Extract of a letter from the Honble Edward Legge, Esq; F. R. S. Captain of his Majesty's ship the Severn, containing an observation of the eclipse of the moon, Dec. 21. 1740. at the Island of St. Catharine on the Coast of Brasil". Philosophical Transactions. 42 (462): 18–19.

- ^ Brattle, Tho.; Hodgson, J. (1704). "An Account of Some Eclipses of the Sun and Moon, Observed by Mr Tho. Brattle, at Cambridge, about Four Miles from Boston in New-England, Whence the Difference of Longitude between Cambridge and London is Determin'd, from an Observation Made of One of Them at London". Philosophical Transactions. 24: 1630–1638.

- ^ Dutton's Navigation and Piloting, 12th edition. G.D. Dunlap and H.H. Shufeldt, eds. Naval Institute Press 1972, ISBN 0-87021-163-3

- ^ As food stores ran low, the crew would be put on rations to extend the time with food This was referred to as giving the crew short rations, short allowance or petty warrant.

- ^ Gould, R.T. (1935). "John Harrison and his timekeepers". The Mariner's Mirror. 21 (2): 115–139.

- ^ a b c Siegel, Jonathan R. (2009). "Law and Longitude". Tulane Law Review. 84: 1–66.

- ^ Wolf, Charles (1902). Histoire de l'Observatoire de Paris de sa fondation à 1793 (in French). Paris: Gauthier-Villars.

- ^ Wolf, A. (1935). History Of Science, Technology And Philosophy: In The 16th And 17th Centuries Volume.1. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Gallois, L. (1909). "L'Académie des Sciences et les Origines de la Carte de Cassini: Premier article". Annales De Géographie. 18 (99): 193–204. JSTOR 23436957.

- ^ Picard, Jean; de la Hire, Philippe (1729). "Pour la Carte de France corrigée sur les Observations de MM. Picard & de la Hire". Mémoires De L' Académie Des Sciences (in French). 7 (7).

- ^ Major, F.G. (2014). "The Longitude Problem". Quo Vadis: Evolution of Modern Navigation: The Rise of Quantum Techniques. New York: Springer. pp. 113–129. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8672-5_6.

- ^ a b Carpenter, James (1872). "Greenwich Observatory". The Popular Science Review. 11 (42): 267–282.

- ^ "The History of HM Nautical Almanac Office". HM Nautical Almanac Office. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b "Nautical Almanac History". US Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ^ "MONOGRAPHIE DE L'AURORE - Corvette -1766". Ancre. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Ship's chronometer from HMS Beagle"

- ^ Sobel, Dava, Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time, Walker and Company, New York, 1995 ISBN 0-8027-1312-2

- ^ The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris, for the year 1767, London: W. Richardson and S. Clark, 1766

- ^ Bowditch, Nathaniel (2002). . . Unites-States: National Imagery and Mapping Agency. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^

Britten, Frederick James (1894). Former Clock & Watchmakers and Their Work. New York: Spon & Chamberlain. pp. 228. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

In the early part of the present century the reliability of the chronometer was established, and since then the chronometer method has gradually superseded the lunars.

- ^ Brooks, Frederick J. (1995) [1975]. The Mythical Man-Month. Addison-Wesley. p. 64. ISBN 0-201-83595-9.

- ^ "Re: Longitude as a Romance". Irbs.com, Navigation mailing list. 2001-07-12. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ R. Fitzroy. "Volume II: Proceedings of the Second Expedition". p. 18.

- ^ The Nautical Almanac Abridged for the Use of Seamen, 1924

- ^ Timekeeping at the U.S. Naval Observatory

- ^ David Baron (2017). American Eclipse. ISBN 9781631490163.

- ^ Lombardi, Michael A., ""Radio Controlled Clocks"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2007-10-30. (983 KB), Proceedings of the 2003 National Conference of Standards Laboratories International, August 17, 2003