A Screaming Man

| A Screaming Man | |

|---|---|

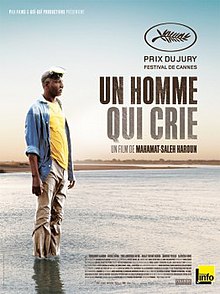

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mahamat Saleh Haroun |

| Written by | Mahamat Saleh Haroun |

| Produced by | Randy Florence |

| Starring | Youssouf Djaoro |

| Cinematography | Laurent Brunet |

| Edited by | Marie-Hélène Dozo |

| Music by | Wasis Diop |

Production companies | Pili Films Goï Goï Productions |

| Distributed by | Pyramide Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Countries | France Belgium Chad |

| Languages | French Chadian Arabic |

| Budget | €2 million |

A Screaming Man (French: Un homme qui crie) is a 2010 drama film by Mahamat Saleh Haroun,[1] starring Youssouf Djaoro and Diouc Koma.[2] Set in 2006, it revolves around the civil war in Chad, and tells the story of a man who sends his son to war in order to regain his position at an upscale hotel. Themes of fatherhood and the culture of war are explored. Principal photography took place on location in N'Djamena and Abéché. The film won the Jury Prize at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.[1]

Plot

Adam (Youssouf Djaoro), a former central African swimming champion, is the pool attendant at a luxury hotel.[3] He is known as Champ. As an economy measure Mrs. Wang, the manager, demotes him to gate security guard and his son Abdel is made pool attendant. The local chief pressures Adam to give money towards Chad's fight against rebel forces, chastising him for not attending a cause meeting. The chief tells Adam of how he sent his 17-year-old son to fight in the war. He also tells Adam he has three days to pay money to support the cause. To regain his post Adam volunteers Abdel for the Chadian Ground Forces, and soldiers come to the family home and forcibly draft Abdel. Adam resumes his job as pool attendant.

A 17-year-old woman, Abdel's pregnant girlfriend, arrives at Adam's home and is taken in and cared for. The conflict worsens and the townspeople flee. Adam tells his daughter-in-law of his treachery and she breaks down. Adam rethinks his position and takes his motorcycle with sidecar to the war zone to bring Abdel home. He finds Abdel seriously wounded- eye, neck, right arm and abdomen. That night Adam takes Abdel from the hospital, places him in the sidecar and heads for home. On the journey Abdel says he wishes to swim in the river. Abdel dies as they reach the river. Adam floats the corpse in the river, which takes the body away.

Cast

The film features;[4]

- Youssouf Djaoro as Adam

- Diouc Koma as Abdel

- Emile Abossolo M'Bo as district chief

- Hadjé Fatimé N'Goua as Mariam

- Marius Yelolo as David

- Djénéba Koné as Djeneba

- Heling Li as Mme Wang

- John Mbaiedoum as Etienne

- Abdou Boukar as Le maître d'hôtel

- Gerrard Ganda Mayoumbila as Le sous-officer

- Tourgodi Oumar as Soldat barrage 2

- Hilaire Ndolassem as Radion speaker (voice)

- Remadji Adele Nagaradoum as Souad

- Sylvain Nbaikoubou as Le nouveau cuisiner

- Fatimé Nguenabaye as La voisine

- Mahamat Choukou as Soldat barrage 1

- Hadre Dounia as Joune Soldat blessé

- Laure Cadiot

Themes

Adam's and Abdel's relationship is the main focus of the film's story, and according to the director it relates to modern day Chad: "Between the father and the son is the transportation of memory, genes, and culture. It's particularly important here because men conduct the war in Chad. The unrest in Chad has lasted 40 years and it's the father who has transmitted the culture of war to his son, because otherwise there is no reason for the son to get involved."[5] Mahamat Saleh Haroun intentionally resisted going into detail about the civil war in Chad and politics: "The film recounts the point of view of this character and he hasn't got a position with the rebels or the government; to his life the two forces are abstract and so it would not matter if he was for the rebels or the government as this would not stop the war."[5]

The film's title is a quotation from the poetry collection Return to My Native Land by Aimé Césaire. The full sentence is "A screaming man is not a dancing bear".[6] Haroun says that the main character Adam is "screaming against the silence of God, it's not a scream against adversity".[7]

Production

The idea for the film came in 2006 during the production of Daratt. On 13 April rebel forces entered N'Djamena, the Chadian capital, where Haroun was filming, and production was immediately put on hold. The film crew, including the young lead actor who was turning 18 on the very day, were trapped in the desert with no means of communication. This inspired Haroun to try to capture the feeling of imprisonment he experienced during the event.[8]

The French company Pili Films and Chad's Goï Goï Productions produced the film together. Additional co-production support was provided by the Belgian company Entre Chiens et Loups. The two million euro budget included support from the French National Center of Cinematography, and pre-sales investment from Canal +, Canal Horizons, Ciné Cinéma and TV5Monde.[6]

Filming took place during six weeks on location in Chad, starting 30 November 2009.[6] Many of the extras in the film were actual hotel employees, tourists and soldiers who Haroun asked to perform as themselves for the sake of realism.[5] The director recounted the filming in N'Djamena as unproblematic. However, when the crew filmed in Abéché, a stronghold for rebel forces, there was a constant fear among everybody involved in the production. Haroun saw it as a challenge to finish the film before something would happen, while he also tried to take advantage of the genuine tension on the set.[9]

Release

A Screaming Man premiered on 16 May 2010 in competition at the 63rd Cannes Film Festival.[10] It was subsequently shown at several festival venues including the Toronto International Film Festival.[11] Pyramide Distribution released it in French theaters on 29 September 2010.[12]

Critical response

The film received positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 89% out of 36 professional critics gave the film a positive review, with a rating average of 7.2/10.[13]

Thomas Sotinel reviewed the film for Le Monde. He thought it had an undeniable beauty, but continued, "This beauty is also fragile, because Mahamat Saleh Haroun didn't have quite all the necessary resources for the full expression of his vision. It is especially annoying that the sequence with the exodus of N'Djamena's population well shows that the filmmaker can switch to grand format when his subject commands it."[14]

Julien Welter of L'Express appreciated Haroun's choice of neither making a large-scale analysis of the conflict in Chad, nor a melodrama about the suffering it has brought. Welter's main concern was that he thought the quality of the script dropped during the third act, but ended the review by proclaiming Haroun as "more than ever an artist to follow."[15]

American film critic Roger Ebert stated that he "greatly admired" the film, noting, "The unique quality of the movie is to look at Adam's life, the way he values his job almost more than his son, and the way status conferred by a Western hotel has bewitched him."[16]

Accolades

The film received the Cannes Film Festival's Jury Prize. This made Haroun not only the first Chadian director to have a film in the main competition, but also the first to win one of the festival's awards.[17] A Screaming Man won the Silver Hugo for best screenplay at the 46th Chicago International Film Festival. Youssouf Djaoro was awarded the Silver Hugo for best actor.[18] At the 2011 Lumière Awards, decided by foreign journalists based in Paris, the film won the prize for Best French-Language Film from outside France.[19] The film was nominated for a Magritte Award in the category of Best Foreign Film in Coproduction in 2012, but lost to Romantics Anonymous.[20]

References

- ^ a b "A Screaming Man – review". The Guardian. 14 May 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "A Screaming Man / Un homme qui crie | African Film Festival, Inc". Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Gabara, Rachel (September 2013). "FEATURE FILMS - Mahamat-Saleh Haroun. A Screaming Man. Original title: Un homme qui crie. 2010. Chad and France. French and Chadian Arabic, with English subtitles. 91 min. Film Movement and Pyramide International. $24.95". African Studies Review. 56 (2): 227–228. doi:10.1017/asr.2013.68. ISSN 0002-0206.

- ^ Haroun, Mahamat-Saleh (13 April 2011), Un homme qui crie (Drama), Pili Films, Entre Chien et Loup, Goi-Goi Productions, retrieved 28 January 2022

- ^ a b c Aftab, Kaleem (21 July 2010). "Visible Africa: Cannes winner Mahamat-Saleh Haroun". The National. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Lemercier, Fabien (23 October 2009). "Haroun readies to shoot Screaming Man". Cineuropa. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Collett-White, Mike (16 May 2010). "Father-Son Film in War-Torn Chad Lights up Cannes". af.reuters.com. Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Carpentier, Mélanie (May 2010). "Interview de Mahamat-Saleh Haroun". Evene (in French). Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Cuyer, Clément (29 September 2010). "'Un homme qui crie' : rencontre avec Mahamat Saleh Haroun". AlloCiné (in French). Tiger Global. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "The screenings guide" (PDF). festival-cannes.com. Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ "A Screaming Man". tiff.net. Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ "Un Homme qui crie". AlloCiné (in French). Tiger Global. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ A Screaming Man - Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Sotinel, Thomas (29 September 2010). "'Un homme qui crie' : dans le chaos tchadien, la tragédie d'Adam, père déchu en quête de rédemption". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

Cette beauté est aussi fragile, parce que Mahamat Saleh Haroun n'a pas eu tout à fait les moyens nécessaires à la pleine expression de sa vision. C'est d'autant plus rageant que la séquence de l'exode de la population de N'Djamena montre bien que le cinéaste sait passer au grand format lorsque son propos le commande

- ^ Welter, Julien (28 September 2010). "Un homme qui crie". L'Express (in French). Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

Mahamat-Saleh Haroun est plus que jamais un artiste à suivre.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (24 May 2010). "Cannes postmortem. Is that the wrong word?". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Chang, Justin (23 May 2010). "'Uncle Boonmee' wins Palme d'Or". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "46th Chicago International Film Festival Award Winners Announced". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ^ Lemercier, Fabien (17 January 2011). "Of Gods and Men crowned Best Film at Lumières". Cineuropa. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Engelen, Aurore (10 January 2012). "Nominations announced for 2nd Magritte Awards". Cineuropa. Retrieved 12 January 2013.