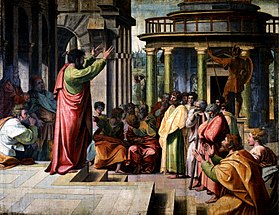

Areopagus sermon

The Areopagus sermon refers to a sermon delivered by Apostle Paul in Athens, at the Areopagus, and recounted in Acts 17:16–34.[1][2] The Areopagus sermon is the most dramatic and most fully-reported speech of the missionary career of Saint Paul and followed a shorter address in Lystra recorded in Acts 14:15–17.[3]

History

Paul had encountered conflict as a result of his preaching in Thessalonica and Berea in northern Greece and had been carried to Athens as a place of safety. According to the Acts of the Apostles, while he was waiting for his companions Silas and Timothy to arrive, Paul was distressed to see Athens full of idols. Commentator John Gill remarked:

- his soul was troubled and his heart was grieved, …he was exasperated and provoked to the last degree: he was in a paroxysm; his heart was hot within him; he had a burning fire in his bones, and was weary with forbearing, and could not stay; his zeal wanted vent, and he gave it.[4]

So Paul went to the synagogue and the Agora (Greek: ἐν τῇ ἀγορᾷ, "in the marketplace") on a number of occasions ('daily'),[5] to preach about the Resurrection of Jesus.

Some Greeks then took him to a meeting at the Areopagus, the high court in Athens, to explain himself. The Areopagus literally meant the rock of Ares in the city and was a center of temples, cultural facilities, and a high court. It is conjectured by Robert Paul Seesengood that it may have been illegal to preach a foreign deity in Athens, which would have thereby made Paul's sermon a combination of a "guest lecture" and a trial.[6]

The sermon addresses five main issues:[3]

- Introduction: Discussion of the ignorance of pagan worship (verses 23–24)

- The one Creator God being the object of worship (25–26)

- God's relationship to humanity (26–27)

- Idols of gold, silver and stone as objects of false worship (28–29)

- Conclusion: Time to end the ignorance (30–31)

This sermon illustrates the beginnings of the attempts to explain the nature of Christ and an early step on the path that led to the development of Christology.[1]

Paul begins his address by emphasizing the need to know God, rather than worshiping the unknown:

"As I walked around and looked carefully at your objects of worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD. So you are ignorant of the very thing you worship — and this is what I am going to proclaim to you."

In his sermon, Paul quotes from certain Greek philosophers and poets, namely in verse 17:28. He alludes to passages from Epimenides[7] and from either Aratus or Cleanthes.

Paul then explained concepts such as the resurrection of the dead and salvation, in effect a prelude to the future discussions of Christology.

After the sermon a number of people became followers of Paul. These included a woman named Damaris, and Dionysius, a member of the Areopagus (not to be confused with Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite or Saint Denis, the first Bishop of Paris).

In the 20th century, Pope John Paul II likened the modern media to the New Areopagus, where Christian ideas needed to be explained and defended anew, against disbelief and the idols of gold and silver.[8]

See also

References

- ^ a b McGrath, Alister E. (2006), Christianity: an introduction, pp. 137–41, ISBN 1-4051-0901-7.

- ^ Schnelle, Udo (Nov 1, 2009), Theology of the New Testament, p. 477, ISBN 0-80103604-6.

- ^ a b Mills, Watson E. (2003), Mercer Commentary on the New Testament, pp. 1109–10, ISBN 0-86554-864-1.

- ^ Gill, John. "Gill's Exposition of the Entire Bible". Bible hub. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Acts 17:17

- ^ Paul: A Brief History by Robert Paul Seesengood 2010 ISBN 1-4051-7890-6 page 120

- ^ Harris, J. Rendel. "A Further Note on the Cretans", Expositor Apr. 1907, 332–337. Quote:

- J. Rendel Harris' hypothetical Greek text:

Τύμβον ἐτεκτήναντο σέθεν, κύδιστε μέγιστε,

Κρῆτες, ἀεὶ ψευδεῖς, κακὰ θηρία, γαστέρες ἀργαί.

Ἀλλὰ σὺ γ᾽ οὐ θνῇσκεις, ἕστηκας γὰρ ζοὸς αίεί,

Ἐν γὰρ σοὶ ζῶμεν καὶ κινύμεθ᾽ ἠδὲ καὶ ἐσμέν.

- Translation:

They fashioned a tomb for you, holy and high one,

Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies.

But you are not dead: you live and abide forever,

For in you we live and move and have our being.

- ^ Miller, Vincent J. (2005). Consuming religion: Christian faith and practice in a consumer culture. p. 99. ISBN 0-8264-1749-3.