Asgill Affair

The Asgill Affair was an event that occurred towards the end of the American Revolution. As a result of ongoing murders taking place between the Patriot and Loyalist factions, retaliatory measures were then taken by General George Washington against a British officer, Captain Charles Asgill, condemned to be hanged, in direct contravention of the Articles of Capitulation. To this end lots were drawn amongst 13 British Captains on 27 May 1782. As America's allies, the French monarchy became involved and let it be known that such measures would reflect badly on both the French and American nations. The French Foreign Minister, the comte de Vergennes, wrote to Washington on 29 July 1782 to express these views.[1] After a six-month ordeal, awaiting death daily, the Continental Congress eventually agreed that Asgill should be released to return to England on parole. According to Ambrose Vanderpoel, Asgill did not receive his passport to leave imprisonment in Chatham, New Jersey, until 17 November 1782.[2]

The Asgill Affair

Preceding events

After the capitulation of the British forces at Yorktown in 1781, by April 1782 tit-for-tat murders between the Patriots and Loyalists had become frequent. The Patriots had murdered Philip White, one of the Loyalists fighting in the American Revolution.[3]

A document dated 1 May 1782 in the papers of George Washington records various violent acts taken against people in parts of New Jersey, such as Monmouth County, some of whom are specifically identified as being Loyalists, and among those listed is Philip White for which the paper says:[4]

Philip White Taken lately at Shrewsburry [sic] in Action was marched under a guard for near 16 Miles and at Private part of the road about three Miles from Freehold Goal [sic] (as is asserted by creditable persons in the country) he was by three Dragoons kept back, while Capt. Tilton and the other Prisoners were sent forward & after being stripped of his Buckles, Buttons & other Articles, The Dragoons told him they would give him a chance for his Life, and ordered him to Run—which he attempted but had not gone thirty yards from them before they Shot him.

Philip White's brother, Aaron White, was captured with him, and although originally said that Philip was shot after trying to escape later recanted inasmuch as his statement had been made under threat of death and that his brother had actually been murdered in cold blood.[5]

In an undated Declaration, the Loyalists responded: "We the Refugees having with grief long beheld the Cruel Murders of our Brethren and finding nothing but such measures daily carrying into Execution. We therefore determine not to suffer without taking Vengeance for numerous cruelties and thus begin and have made use of Captain Huddy as the first object to present to Your views and further determine to hang Man for Man as long as a Refugee is left Existing. 'Up goes Huddy for Philip White'"[6]

Patriot response

On 14 April 1782 fourteen men signed a five-page petition, on behalf of the Patriots of Monmouth County, which was hand delivered to George Washington, demanding revenge for the killing of Joshua Huddy. "Monmouth April 14th 1782. John Ivenhoven, Samuel Forman, Thomas Seabrook, William Wilcocks, Peter Forman, Asher Holmes [Huddy's commanding officer], Richard Cox, Elisha Walton, Joseph Stillwill, Stephen Fleming, Barns Smock, John Smock, John Sohanck, and Thomas Chadwick"[7]

Huddy, a captain of the Monmouth Militia and privateer was overwhelmed and captured by Loyalist forces at the blockhouse (small fort) he commanded at the village of Toms River, New Jersey. He was accused of complicity in the death of Philip White. Huddy was conveyed to New York City, then under British control, where he was summarily sentenced by William Franklin (Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin) to be executed .[8]

Huddy was held in leg irons aboard a prison ship until 12 April 1782, when he was taken ashore and hanged, after first being allowed to dictate his last will. Loyalists pinned a note to his chest reading "Up Goes Huddy for Philip White" and his body was left hanging overnight. He was buried at Old Tennent Church[9] by Patriotic supporters. "Huddy's execution caused a great public outcry in New Jersey and throughout the colonies, and immediate calls for bloody vengeance" demanding retribution for Huddy's death, and presented to American commander General George Washington.[8] Huddy's execution was carried out by Richard Lippincott, who was eventually court martialled by the British for this crime.[10]

British response

Sir Henry Clinton, Commander-in-Chief British forces in North America, was angered at news of Huddy's murder and wrote to Governor Franklin, on 20 April 1782, to say so. Having received no reply, Clinton writes to Franklin again, five days later: New York, April 25, 1782 "Sir, I must now repeat my Request for an immediate Answer to my Letter of the 20th Instant, as I have this day directed a Board of General and other Officers to enquire into the Conduct of Captain Lippincott now in Custody by my Order ..."[11]

When the Board of Associated Loyalists realised that one of their number, Lippincott, was to be tried by Court-martial, their President, William Franklin, wrote an impassioned 7-page letter to Sir Henry Clinton, on 2 May 1782, questioning the legality of a military trial concerning any Associated officer who had "never been paid or mustered as soldiers" ... further stating "there is great reason to doubt whether the Offence charged against Captain Lippincott can under all its Considerations, be legally termed a Murder." The letter ends: "We entreat Your Excellency, previous to any trial, to advise and Consult on the principles & distinctions we have suggested ... Guard Yourself against any Public Inconsistencies that may otherwise arise from a Measure, in our Opinion, so irregular and illegal."[12]

The following letter, written by George Washington to General [James] Robertson C-in-C British Forces in North America, dated 5 May 1782, was written two days after Washington had violated a solemn Treaty, which he himself had signed, by ordering General Moses Hazen to arrange a lottery of death, yet he gives Robertson every assurance that the Rules of War will be upheld by him. Copy, "Head Quarters 5 May 1782. Sir, I had the honor to receive Your Letter of the 1st Instant. Your Excellency is acquainted with the determination expressed in my Letter of the 20th of April to Sir Henry Clinton — I have now to inform You that so far from receding from that resolution, Orders are given to designate a British Officer for Retaliation — The time and place are fixed — But I still hope the Result of your Court Martial will prevent this dreadful alternative. Sincerely lamenting the cruel necessity which alone can induce so distressing a Measure in the present instance, I do assure Your Excellency I am as earnestly desirous as you can be, that the War may be carried on agreeable to the Rules which Humanity formed, and the example of the polite Nations recommend; and shall be extremely happy in agreeing with You to prevent or punish every breach of the Rules of War, within the Spheres of our Respective Commands".[13]

By mid-May Clinton is informing the Secretary for the Colonies in Whitehall of the situation regarding Huddy's murder. He wrote to the Right Honourable Wellbore [sic] Ellis Esq on 11 May 1782: "...I cannot, Sir, too much lament the great Imprudence shown by the Refugees on this Occasion – as these very ill timed Effects of their Resentment may probably introduce a System of War horrid beyond Description. Nor can I sufficiently pity my Successor's having the Misfortune of coming to the Command at so disagreeable and critical a Period ... [but] Allowance ought to be made for Men whose Minds may possibly be roused to Vengeance by Acts of Cruelty committed by the Enemy on their dearest Friends ... [however] I cannot but observe that the Conduct of the Board during this whole Transaction has been extraordinary, not to say, reprehensible; ... for the purpose (it is presumed) of exciting the War of indiscriminate Retaliation, which they appear to have long thirsted after."[14]

Washington's solution

On 27 May 1782, lots were drawn at the Black Bear Tavern, Lancaster, Pennsylvania,[15] with Asgill's name being drawn by a drummer boy, together with the paper marked "Unfortunate", which put him under threat of execution.[8] Asgill's fellow officer, Major James Gordon, protested in the strongest terms to both General Washington and Benjamin Lincoln, the Secretary of War, that this use of a lottery was illegal.[16] By 5 June 1782 Washington was most concerned regarding his orders to Brigadier General Moses Hazen to select a conditional prisoner for retaliation. He also wrote to Lincoln seeking his opinion as to the "propriety of doing this".[17] Furthermore Alexander Hamilton wrote to Major General Henry Knox on 7 June 1782 arguing against the execution in the strongest terms, saying "A sacrifice of this sort is intirely [sic] repugnant to the genius of the age we live in and is without example in modern history nor can it fail to be considered in Europe as wanton and unnecessary."[18]

The officers drawing lots at the Black Bear Inn were:[19]

- Officers being held near York:

- From the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards Lt. & Captain[a] Charles Asgill, Lt. & Captain Hon. George Ludlow, Lt. & Captain James Perrin

- From the 2nd Regiment of Foot Guards, Lt. & Captain George Eld, Lt. & Captain Henry Greville

- From the 23rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Fuzileers), Captain Thomas de Saumarez

- From the 76th Regiment of Foot, Captain David Barclay, Captain Samuel Graham

- Officers being held in Lancaster:

- From the 17th Regiment of Foot Captain Lawford Miles

- From the 26th Regiment of Foot Captain Bulstrode Whitlocke

- From the 33rd Regiment of Foot Captain James Ingram

- From the 80th Regiment of Foot Captain Alexander Arbuthnot, Captain William Hawthorn (also known as John Hathorn)

After lots were drawn on 27 May 1782, Hazen, who had been in charge of the proceedings, wrote that same day to Washington to inform him that Major James Gordon had identified unconditional prisoners, but that Asgill was on his way to imprisonment for the next six months, where he awaited the gallows on a daily basis. He also told Washington that his orders of 3 May[20] and 18 May 1782[21] had been painful for him to carry out (his orders from Washington of 18 May had told him to include conditional prisoners, who were protected by treaty). "Since I wrote the above Majr Gordon has furnished me with an Original Letter of which the inclosed [sic] is a Copy, by which you will see we have a Subaltern Officer and unconditional Prisoner of War at Winchester Barracks. I have also just received Information that Lieut. Turner, of the 3rd Brigade of Genl Skinner's New-Jersey Volunteers is in York Goal [sic]—but as those Informations [sic] did not come to Hand before the Lots were drawn, and my Letters wrote to your Excellency and the Minister of War on the Subject, and as I judge no Inconveniency [sic] can possibly arise to us by sending on Capt. Asgill, to Philadelphia, which will naturally tend to keep up the Hue and Cry, and of course foment the present Dissentions amongst our Enemies, I have sent him under guard as directed. Those Officers above-mentioned are not only of the Description which your Excellency wishes, and at first ordered [on 3 May], but in another Point of View are proper Subjects for Example, been Traitors to America, and having taken refuge with the Enemy, and by us in Arms. It have [sic] fallen to my Lot to superintend this melancholy disagreeable Duty, I must confess I have been most sensible affected with it, and [do] most sincerely wish that the Information here given may operate in favour of Youth, Innocence, and Honour".[15][22]

27 May 1782 - the drawing of lots

In a letter to his mother (Lancaster, 29 May 1782) Lieutenant and Captain Henry Greville, 2nd Foot Guards (one of the 13 officers who drew lots) wrote: "General Hazen whose behaviour throughout the whole affair has been Noble and Generous, immediately granted his [Gordon's] request and again appologized [sic] for being Obliged to execute his orders, he said he was but a Servant and as such must behave" ..."Asgylle, [sic] tho' evidently affected with his Fate, yet bore it with uncommon resolution, he thanked Genl Hazen in the prettyest [sic] style for the politeness he had shown him, and took his leave. I walked home with him and endeavoured to keep up his spirits, at first he was melancholy and thoughtfull, [sic] seemingly very unhappy, but it gradually wore off, and no person to have been in his company could have supposed he was doomed to die." ... "We are all at this moment waiting with anxiety to know his [Asgill's] fate, we think and hope the confinement and anxiety of mind will be his greatest punishment, every Person in this Town was affected at his Missfortune [sic]. There were more tears shed here the 27th May than ever fell on any occasion."[23]

According to Mayo, Asgill wrote a farewell letter to his family, an account of which was published in the New York Packet on 10 October 1782 (which states he is only 15 years of age)[24] and she summarises the content of the article: "It was no long tale that young Charles wrote. Those four in England knew how he loved them. To try to say it now would only cast loose his wildly struggling nerves. So, in the fewest words, without self-pity, with out [sic] lament, he told them his fate, and took farewell. Then, turning to his father, he made his only plea. Long before this letter could reach England the end would have come. But would that dear father pardon him, dead, for having set duty to King and country above filial obedience? Could he hold the child that was gone in forgiveness and even in blessing?" The newspaper article concludes by stating that his father was too ill to be told this news.[25][26]

Major James Gordon of the 80th Regiment of Foot (Royal Edinburgh Volunteers) who was in charge of British prisoners, wrote to General Sir Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, Commander-in-Chief, America, on 27 May 1782 saying: "The delicate Manner in which General Hazen communicated his Orders, shews [sic] him to be a Man of real Feelings, and the mild Treatment that the Prisoners have met with since we came to this Place, deserves the warmest Acknowledgements of every British officer."[27]

Brigadier General Moses Hazen's role

Mayo tells us of Hazen's compassion towards the selected victim – there is no doubt that he was genuinely aggrieved at the part he had been ordered to play: "As he [Hazen] rode at Gordon's side [as they accompanied Asgill on his journey to Chatham, via Philadelphia, at which point Hazen bade his farewell], bitterly ruminating, Hazen racked his brains to think of those influential in Philadelphia, seat of the Government, whose sympathies and aid might be enlisted in Asgill's behalf. Such men he named, advising how to reach them. Together they talked of the letters that Gordon had written and that Hazen's help had sped on their way. Those letters ought to be given all possible time to reach their destination before the next move could be made. So Gordon declared; so Hazen agreed. And with the Scot's request that the journey to Philadelphia - seventy miles - be taken, therefore, as slowly as possible, the American at once fell in. Finally the moment came when Hazen must turn back. As he did so, his last act was to order the officer commanding the escort that in all matters not at variance with the safekeeping of the prisoner he render strict obedience to Major Gordon's desires. Here were two men born to understand each other the American and the Scot. Of the two it were hard, perhaps, to guess which, at their parting, felt the sadder — the one for the rôle he had been forced to play; the other for a true man driven to a deed that sickened him."[28]

Washington, having specifically ordered Hazen, on 18 May, to select conditional officers in the drawing of lots (if no unconditional officers were available), when he receives Hazen's letter of 27 May he replies, on 4 June, telling him that he has made a "mistake". What was Hazen to do? His orders had been clear and urgent; and no unconditional prisoners had been sent on to Lancaster in time for the drawing of lots. Hazen was one of the wayside Samaritans in this sorry saga,[29] yet now the blame was being placed firmly on him – indeed, it has gone down in history as a 'misstep by Hazen'. He must have been very disappointed to receive the following words from his commander-in-chief, as recorded by Vanderpoel. "Head Quarters, 4th June, 1782. Sir, I have received your favr of the 27th. May, and am much concerned to find, that Capt Asgill has been sent on, notwithstanding the Information, which you had received, of there being two unconditional Prisoners of War in our possession. I much fear, that the Enemy, knowing our delicacy respecting the propriety of Retaliating upon a Capitulation officer in our Care, and being acquainted that unconditional prisoners are within our power, will put an unfavorable [sic] Construction upon this Instance of our Conduct. At least, under present Circumstances Capt Asgill's application to Sir Guy Carleton will, I fear, be productive of remonstrance and Recrimination only, which may possibly tend to place the Subject upon a disadvantageous footing. To remedy therefore as soon as possible this mistake, you will be pleased immediately to order, that Lieut Turner, the officer you mention to be confined in York Gaol, or any other prisoner who falls within my first Description, may be conveyed on Phila under the same Regulations and Directions as were heretofore given, that he may take the place of Capt Asgill. In the mean Time, lest any misinformation respecting Lt. Turner, may have reached you, which might occasion further Mistake and Delay, Capt Asgill will be detained untill [sic] I can learn a Certainty of Lieut Turner's or some other officer's [sic] answering our purpose; and as this Detention will leave the Young Gentleman now with us in a very disagreeable State of Anxiety and Suspense, I must desire that you will be pleased to use every means in your power, to make the greatest Despatch in the Execution of this order."[30]

Nevertheless, throughout the following six months no unconditional British captains were ever brought forward to take the place of Asgill, in spite of the unconditional Captain John Schaack being imprisoned in Chatham, New Jersey for this very purpose.[31]

Under close arrest in Chatham

On reaching Chatham, New Jersey, Asgill was under the jurisdiction of Colonel Elias Dayton, and in close proximity to the people of Monmouth County, who wished him to atone for Huddy's execution. Dayton housed Asgill in his own quarters and treated him kindly. But in a P.S. to his letter to Dayton of 11 June 1782, Washington wrote telling him to send Asgill to the Jersey Lines under close arrest, adding that he should be "treated with all the Tenderness possible, consistent with his present Situation".[32] However, Dayton responded to Washington, on 18 June 1782, saying that Asgill was too ill to be moved, thereby showing much compassion to his prisoner.[33] It is not known why, when recovered, Asgill was sent under close arrest to Timothy Day's Tavern. While he was under arrest at the tavern, he suffered from beatings; deprivation of edible food and letters from his family were withheld from him.[15]

the provisions delivered to me at the early period of my confinement were exceedingly bad till the Landlord procurd me better nourishment at an exorbitant price upon finding that I had a considerable sum of Money. I was repeatedly & almost continuously insulted not indeed by the Officers who guarded me They & particularly Col Drayton [sic] behavd civily [sic] & I was beat violently & cruelly for refusing to answer the impertinent questions put to me by a visitor who thought himself entitled to be satisfied on every particular having paid for his admission — These were the Comforts I enjoyd These were the attentions I receivd from General Washington —[34]

On page 44 of Summit New Jersey, From Poverty Hill to the Hill City by Edmund B. Raftis there appears a map of Chatham in 1781. Clearly marked is the home of Colonel Dayton and also Timothy Day's Tavern, the first and second locations of Asgill's imprisonment. The map also shows that the population of Chatham at that time was approximately 50 homesteads, most of these homes having been notated with the names of the occupants. A 21st century map shows that the present day location of Timothy Day's Tavern would be in the vicinity of 19 Iris Road and Dayton's house was on what is now Canoe Brooke Golf Course.[15]

Vanderpoel mentions that: "THROUGH the long and weary months of the summer of 1782 Captain Asgill remained at Chatham in a state of constant anxiety and suspense, dreading from day to day that the order for his execution would be issued. To add to his distress, it was erroneously reported in America during his captivity that his father, Sir Charles Asgill, who was known to be seriously ill, had passed away, and his captors unintentionally caused him a painful shock by addressing him with the family title; though later an express from New York gave him reason to hope that the report of his father's death was incorrect."[35]

His anxiety levels were high, never knowing when the call would come for him to go to the gallows, and he also felt anxious that family and friends in Europe were under the misguided impression that the parole awarded him (in order to restore his health, which had severely deteriorated during his close custody at Timothy Day's Tavern) meant he was no longer in danger of execution. In 1786, Asgill wrote:[34]

relative to the permission I receivd to [ride] — I reply that I did indeed receive such a permission after four months close confinement when my Health had been impaired & my Constitution reducd by a long series of Hardships & insults —

Ambrose Vanderpoel reproduces some of his letters expressing this fear: Asgill to Elias Dayton: "Chatham, Sep'br. 6th. 1782. Least by any accident you should not receive my letter of the 5th. inst. which an officer of the Jersey line took charge of, I judged it would be best to prevent your conceiving me remiss in answering yours to send this duplicate by the Post, thanking you for your very early attention in writing to me, tho I am sorry my request cannot be complied with — when you first informed me that it was General Washington's orders that I should be admitted on Parole, I naturally concluded that every Idea of retaliating upon me for the Murder of Capt. Huddy was given up by his Excellency, & my only remaining wish to compleat [sic] my happiness was, that you would procure Genl Washington's permission for me to go to Europe, buoyed with the hopes of soon revisiting those who must have long mourned my unhappy confinement, & since that time till the Receipt of yours, my Health and Spirits, which you with pleasure seemed to Notice, daily mended, but now how great & afflicting is the change, those pleasing Ideas are entirely vanished, & the prospect of continuing much longer in this dreadful Suspense will I fear if at a future time the decision proves favourable, be too late, to render comfort either to me or my aged Father. As soon as you become informed of the Determination of Congress, I hope you will be kind enough to communicate the Resolve to me — being absent from the Inn at Morris, where your letter was left, I did not hear of it till the next Day, & then it was received opened. Permit [me] to intreat [sic] you to intercede with Genl Washington in my behalf, & assist in relieving my present anxiety. believe me Dear Sir with Gratitude for your feeling & Humane conduct to me,..." Asgill writes to Dayton again, six days later:[36]

Chatham, Sept'r 12th. 1782. Sir, I hope my great anxiety to obtain permission to return to Europe will plead my excuse for giving you so much trouble, the more I reflect on my present Situation the more desirous I am for the accomplishment of my Wishes, as I conceive myself by being admitted on Parole in every respect as before this unhappy affair, & not the Object of Reprisal. the Confidence I have in your goodness of Heart which prompts you to assist the truly unfortunate, leaves me no doubt that the consideration of the consequence that must follow much further delay in this affair will weigh with you to use your utmost endeavours toward procuring me Genl. Washington's Permission to revisit Friends in England. Believe me with Gratitude & Esteem, Your Obligd Ser't Chas. Asgill.

As a consequence of the conditions Asgill experienced at the tavern, he wrote again to Washington on 27 September 1782, stating "I fear fatal consequences may attend much longer delay" and goes on:[37]

I hope when your Exy considers that I am not in the situation of a Culprit, that while on Parole I never acted contrary to the Tenor of it that my Chief motives for being so eager for further Enlargment is on account of my Family, these facts, I hope, will operate with your Excellency, to reflect on my unhappy Case, & to relieve me from a state, which those only can form any Judgment of, who have experienced the Horrors Attending it.

Three weeks later, still not knowing his fate (a further month would pass before he knew he was free to return home), Asgill decides to write to Washington once more, begging to be placed under close arrest again, since parole has made no difference to his awaiting the gallows daily:[38]

Chatham Octr 18th

Sir — I have been honored [sic] with your Excellys Letter & am exceedingly Obliged by the attention to which mine received. I will not intrude on your time by repetitions of my Distress, which has lately been increased by accounts that my Father is on his Death Bed. I have only to entreat as it may be a long while ere Congress finally determine, that your Excellency will be pleased to

allow me to go to New York on Parole & to return in case my reappearance should hereafter be deemed necessary — if this request cannot be granted I hope your Excellency will give orders that my Parole may be withdrawn, as that Indulgence without a prospect of further Enlargement affords me not the least satisfaction, I had rather endure the most severe confinement than suffer my Friends to remain as at present decieved [sic], fancying ever since my first admission on Parole, that I was entirely liberated & no longer the Object of retaliation — if your Excelly could form an Idea of my sufferings I am convinced the trouble I give would be excused. I have the Honor to be your Excellency's Most Obedt Hbl Servt

R. Lamb, late Serjeant [sic] in the Royal Welch Fuzileers [sic] wrote:[39]

As I am in possession, of more accurate information on this subject than most who have written on American affairs, I shall take the liberty of detailing on the facts. The spirit of political rancor [sic] in America had at this period risen to an uncommon height," ... "Captain Asgill had frequent opportunities of making his escape into New York; his whole guard (so greatly was he beloved by them) offered to come in along with him, if he would provide for them in England. Although these offers must have been very tempting to a prisoner, under sentence of death! yet he scorned to comply, as it would have involved more British officers in trouble. He nobly said: 'As the lot has fallen on me, I will abide by the consequences.'" ... "Indeed the captain received very bad usage throughout his confinement; he was constantly fed upon bread and water. This harsh treatment constrained him to send his faithful servant to New York to receive and carry letters for him. This man ran great hazard in passing over the North River to New York.

News reaches London

Lady Asgill, and her daughters, first heard the news of events in Chatham, when Captain Gould, a friend of Asgill's, had been repatriated and went to call on them in Richmond:[40]

On arriving at the house of Lady Asgill he was shown into a room where Lady Asgill and another lady were seated, and when he made the sad communication both ladies swooned away and fell, as it were, lifeless on the floor. The surprise and horror of the servant, who was immediately summoned by Capt. Gould, may well be imagined when, on entering the apartment, he found the two ladies apparently lifeless on the floor, thinking that Capt. Gould had murdered them. Assistance, however, and restoratives were quickly at hand, but the shock was necessarily great. It fortunately happened that Lady Asgill had great influence with the Queen of France, who succeeded in preventing the sentence being carried into execution.

-

The London Chronicle Vol. LII, No 3998 From Saturday 13 July to Tuesday 16 July 1782 has articles on three of its pages.

-

"Although the situation of Mr. Asgill is not a pleasant one, there is every reason to suppose it not dangerous, as to going to his life;..."p. 51

-

Letter from George Washington to Sir Henry Clinton April 21, 1782 together with Clinton's reply to Washington appear on p. 53

-

"Capt. Asgill, now under strict confinement in Philadelphia...destined to be the object of Gen. Washington's...retaliation" appears on p. 55

Ambrose Vanderpoel states that: "Intelligence of Asgill's plight reached London on or about the 13th of July."[41] So, by the summer of 1782 Ministers in Whitehall, London, were becoming involved in the events taking place in America. King George III was informed, and was expressing his views too: On 10 July 1782 a letter from Sir Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney, the British Home Secretary, to Sir Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, Commander-in-Chief, North America, read:[42]

Whitehall. Private. Sir, The unhappy State of the Family of Captain Asgill of the Guards has occasioned my giving you this mantle. The News of that officer's being confined by Gen. Washington in direct contradiction to the Articles of Capitulation has struck every body [sic] with astonishment. It is most probable that the current fate of this unfortunate affair will have been determined before this reaches you. But in case it should not, I can not help suggesting to your Excellency, that an application to M. de Rochambeau as a Party in the Capitulation seems to me a proper and necessary step. I think it most probable, that you have taken this measure before this time, but the time of extreme affliction is something which is represented to me as existing at present in that unhappy family makes it impossible for me to refuse in taking a step that may afford them any hope or consolation. M. de Rochambeau, and indeed Mr Washington too must expect that the execution of an officer under the circumstances of Captain Asgill must destroy all future confidence in Treatys [sic] & Capitulations of every kind, & introduce a kind of War that has ever been held in abhorrence among Civilized Nations.

Again, on 14 August 1782, Sir Tomas Townsend is writing to Sir Guy Carleton:[43]

Whitehall. Sir, I had the honor [sic] of receiving on the 11th of last Month and laying before The King, your Letter No 4 of the 14th June, ─ with the several Inclosures [sic] relative to the unauthorized Execution of Captain Huddy of the New Jersey Militia by Capt Lippencott [sic], and of the unprecedented and extraordinary resolution of Genl Washington with regard to Capt Asgill of the Brigade of Guards; and however unpleasing the subject may have been to His Majesty's Ear, He cannot too highly approve of the very judicious Measure you have taken thereupon, and rests in full confidence that the footing on which it appears to have been placed by your Letter No 9 of the 17th of June, that Justice has taken its course, and that the perplexing affair has come to a final decision. ...

Four days later, on 18 August 1782, Sir Guy Carleton writes to Sir William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, the Prime Minister:[44]

Lord, ... The Arrest of Captain Asgill for the avowed Purpose of Retaliation, and the further Arrest of Captain Schaack, who is not protected by the Capitulation of York Town, together with the Perplexities which have attended the Trial of Captain Lippencot [sic], and which have produced his Acquittal, and concerning which so many Documents are transmitted to Your Lordship, are Matters which now approach to some Conclusion. The present Crisis I thought favourable, and I have accordingly written to General Washington and accompanyed [sic] my Letter with the Minister of the Court Martial, and such other Documents as I thought necessary for my Purposes and his Information; but what his Resolutions or those of Congress will be in this Matter I am Yet to learn. ...

King Louis XVl and Queen Marie Antoinette's role

On hearing of her son's impending execution, Asgill's mother, Sarah Theresa, Lady Asgill (who was of French Huguenot origin), wrote to the French court, pleading for her son's life to be spared.[8][45] King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette ordered the comte de Vergennes, the Foreign Minister, to convey to General Washington their desire that a young life be spared.[8][46] Since France had also signed the Treaty of Capitulation, protecting prisoners of war from retaliation, they too were bound to honour the terms. Asgill was thus protected by the 14th Article of Capitulation in the document of Cornwallis's surrender, safeguarding prisoners of war.[47] Vergennes writes to Washington on 29 July 1782:[48]

There is one consideration, Sir, which, tho it is not decisive, may have an influence on your resolutions — Capt. Asgill is doubless [sic] your Prisoner, but he is among those whom the Arms of the King contributed to put into your hands at York Town Altho' this circumstance does not operate as a Safe Guard, it however justifies the interest I permit my self to take in this affair. If it is in your power Sir to consider & to have regard to it you will do what is agreeable to their Majesties

Mayo sums up the French diplomacy on display in Vergennes letter:[49]

Vergennes's letter was a masterpiece of tact and diplomacy hiding the iron hand. Vergennes had not reminded them that Article One of the Yorktown Capitulation declared the vanquished British forces "surrender as prisoners of war to the combined forces of America and France." He had not reminded them that Article Fourteen of that treaty promised freedom from reprisals to every capitulating man. He had not pointed out to them, in so many words, that France's claim upon the British prisoners was at least equal to their own; neither that France's signature, at the treaty's foot, compelled her to defend her good faith against her ally's default. Instead, clear through the imperative involved, he disclaimed both the right and the wish to use it. And so doing, he held the door wide open for that face-saving exit that had seemed, until this "wonderful intervention of Providence," as hopeless as it was desirable.

In her desperation, Lady Asgill sent a copy of Vergennes letter to Washington herself, by special courier, and her copies of correspondence reached Washington before the original from Paris.[50] She sought the help of Cornwallis, and it may be that the enclosure to his letter was, indeed, the time she employed a special courier to speed Vergennes letter to Washington, of 29 July, on its way to America. "Earl Cornwallis to Sir Guy Carleton 4 August 1782. Calford. — Dear Sir, Lady Asgill, whose situation has been most distressing, is very anxious to have the inclosed [sic] letter transmitted to Genl. Washington. I think I convinced her that it was impossible that the letter could arrive in America time enough to be of any use, but yet she was unwilling to give up sending it, I have therefore taken the liberty of inclosing [sic] it to Your Excellency, that you may determine whether it ought to be sent to Genl. Washington, if, contrary to all probability, you should receive it before that unfortunate transaction is finally settled."[51] Vergennes' letter, enclosing that of Lady Asgill, was presented to the Continental Congress on the very day they were proposing to vote to hang Asgill, since "A very large majority of Congress were determined on his execution, and a motion was made for a resolution positively ordering the immediate execution."[52][53] But "On 7 Nov. an act was passed by Congress releasing Asgill".[54] Congress's solution was to offer Asgill's life as "a compliment to the King of France."[52]

The Continental Congress decides

From Ambrose Vanderpoel we learn that Asgill's fate was on a knife-edge in Congress: "One of the members of Congress at that time was Elias Boudinot of Elizabeth, N. J., who thus recorded in his journal the circumstances under which these letters were received, and the effect which they produced: A very large Majority of Congress were determined on his [Asgill's] Execution, and a Motion was made for a Resolution positively ordering the immediate Execution. Mr. Duane & myself considering the Reasons assigned by the Commander in Chief conclusive, made all the Opposition in our Power. We urged every Argument that the Peculiarity of the Case suggested, and spent three Days in warm Debate, during which more ill Blood appeared in the House, than I had seen. Near the close of the third Day, when every Argument was exhausted, without any appearance of Success, the Matter was brought to a Close, by the Question being ordered to be taken. I again rose and told the House, that in so important a Case, where the Life of an innocent Person was concerned, we had (though in a small Minority) exerted ourselves to the utmost of our Power. We had acquitted our Consciences and washed our Hands clean from the Blood of that Young Man. ... The next Morning as soon as the Minutes were read, the President announced a Letter from the Commander in Chief. On its being read, he stated the rec't of a letter from the King and Queen of France inclosing [sic] one from Mrs. Asgill the Mother of Capt. Asgill to the Queen [she actually wrote to the comte de Vergennes], that on the Whole was enough to move the Heart of a Savage. The Substance was asking the Life of young Asgill. This operated like an electrical Shock. Each Member looking on his Neighbor [sic], in Surprise, as if saying here is unfair Play. It was suspected to be some Scheme of the Minority. The President was interrogated. The Cover of the Letters was called for. The General's Signature was examined. In Short, it looked so much like something supernatural that even the Minority, who were so much pleased with it, could scarcely think it real. After being fully convinced of the integrity of the Transaction, a Motion was made that the Life of Capt. Asgill should be given as a Compliment to the King of France."[55] After much debate Congress agreed that young Asgill should be released on parole to return to England.[52]

In a letter from Robert R. Livingston to Benjamin Franklin, on 9 November 1782, he writes: "Mr Stewart, informing me that he shall set out tomorrow for Paris [where Franklin was negotiating the terms of the peace treaty], will be the bearer of this ... The only political object of a general nature, that has been touched upon in Congress since my last, is the exchange of prisoners, which seems at present to be as far as ever from being effected. The propositions on the side of the enemy were to exchange seamen for soldiers, they having no soldiers in their hands; that the soldiers so exchanged should not serve for one year against the United States; that the sailors might go into immediate service; that the remainder of the soldiers in our hands should be given up at a stipulated price. ... General Carleton has sent out the trial of Lippincott, which admits the murder of Huddy, but justifies Lippincott under an irregular order of the Board of Refugees. So paltry a palliation of so black a crime would not have been admitted, and Captain Asgill would certainly have paid the forfeit for the injustice of his countrymen, had not the interposition of their Majesties prevented. The letter from the Count de Vergennes is made the groundwork of the resolution passed on that subject."[56]

The following correspondence sailed on the Swallow Packet – the same ship and voyage on which Charles Asgill left America – and were received in Whitehall on 17 December 1782, under a covering letter from Sir Guy Carleton to Thomas Townsend, dated 15 November. Carleton enclosed a copy of Congress's directive to free Asgill:[57]

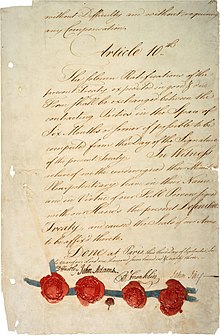

Copy: By the United States in Congress assembled November 7, 1782

On the report of a committee to whom was referred a letter of the 19th of August from the Commander in Chief, a report of a Committee thereon and motions of Mr Williams and Mr Rutledge relative thereto, and also another letter of 25th of October from the Commander in Chief, with a Copy of a letter from the Count de Vergennes dated 29th July last, interceding for Captain Asgil [sic]. –

Resolved, That the commander in Chief be and he is hereby directed to set Capt Asgil [sic] at Liberty.

Signed Cha Thomson Sect

Amongst the correspondence were copies of letters to and from Luzerne (written in French) and Carleton. None of it reached London until Asgill himself had disembarked from his voyage home.[58]

Released from captivity

Once released by Congress, Asgill left Chatham immediately,"...riding for the British lines with Washington's passport in his pocket; riding, day and night, as hard as horse-flesh can bear it. And now, all breathless, all caked with the mire of the road, not pausing to make himself decent, he stands before Sir Guy Carleton [whose headquarters was located at Number One Broadway, Lower Manhattan].[59][60][61] For has he not learned, as he hammered through the streets of New York, that a packet-ship, the Swallow, is weighing anchor for England? Sir Guy sparing formalities, pushing him through, he dashes for the waterside — for the Swallow's moorings. The Swallow had just sailed! In a small boat with a willing crew he makes after her, overhauls her twelve miles and more out, and so is off on the long voyage [home]... As the Swallow skims eastward, making, as it chances, a phenomenally quick run, time wears into the third and fourth month since Asgill's last news from home — since the writing of those impounded family letters. He cannot but be desperately anxious concerning his father, of whose condition he is now aware anxious, too, concerning them all. None the less so in view of the fact that his own last farewell, written home when he learned of the acquittal of Lippencott, may have come to their hand soon after this voyage began."[62]

An escape plan was laid

When Asgill spent those brief moments with Sir Guy Carleton, prior to sailing for home, he handed him a letter from his friend, Major James Gordon. It read as follows: "Major James Gordon to Sir Guy Carleton. 1782, November. Chatham. — Sir, Captain Asgill will have the honour to deliver this to Your Excellency, who is at last set at liberty by a Vote of Congress after a long and disagreeable confinement, which he bore with that manly fortitude that will for ever reflect honour upon himself. During the period that he was close confined he had frequent opportunities of making his escape, and was often urged to do it by anonymous correspondents, one of which assured him that if he did not make use of the present moment an order would arrive next day from General Washington that would put it out of his power for ever. This letter he gave me to read, and at the same time told me (that unless I wou'd advise him to do it) he never wou'd take a step that might be the means of counteracting measures adopted by Your Excellency to procure his release, or might bring one of the officers of Lord Cornwallis's army into the same predicament, and that he had made his mind up for the worst consequences that cou'd happen from rebel tyranny."[63]

Gordon hatched a fail-safe plan for Asgill to be rescued by the British in the event the call to go to the gallows came. This escape plan involved Gordon sacrificing his own life to save Asgill. For this reason Asgill was not told the details of the plan since he would never have agreed.[64][65][66][67] The plan also involved several local ladies, whose identity is still unknown to this day.[68] Mayo tells us that: "This project, so Graham in later time affirmed, 'would have been effected.' That he declared no more, it is safe to say, was because of the women concerned, whom he would not implicate."[69] It pained Asgill deeply that Gordon died in New York, on 17 October 1783, before Asgill could offer him his heartfelt gratitude, in person, for all that he had done for him.[15]

Captain John Schaack was also imprisoned

Asgill also delivered another letter to Carleton, written by Captain John Schaak, the unconditional officer Washington had hoped might be exchanged for Asgill, so he could go to the gallows in his stead. This explains that he had been confined in the prison huts for even longer than Asgill himself. "1782, November 15. Near Chatham. — Requesting His Excellency's aid to extricate him from the prison where he has been confined the last five months without any reason assigned. Marked "By Capt. Asgill." Autograph signed letter." "[70][71][72][73]

Katherine Mayo tells us: "Captain John Schaack of His Majesty's 57th Regiment of Foot was made prisoner, it may be recalled, by Jersey privateersmen on May 20, 1782; and on June 11, by order of General Washington, was put under lock and key in the Jersey Line hutments to serve as substitute for Asgill, should Asgill run away. There and thus Schaack remained, held ready at all times for the emergency. But nothing ever was said of him. Where Asgill's name rang from every tongue, Schaack lay unheard of. Nor was this a matter of accident. Had his presence as an unconditional prisoner side by side with Asgill been publicly known, no useful excuse had remained for not letting Asgill go and hanging Schaack straightway. But a hanging, in terrorem, in Tom Paine's phrase, held values that must end with the jerk of the noose. Therefore the secret was so well kept that even the man himself, mouldering away in his cabin, could do no more than guess at the cause of his singular fate."[31]

Ambrose Vanderpoel explains that it wasn't until 15 January 1783 Washington wrote to Dayton congratulating him on his promotion to brigadier and went on to say: "If Captain Schaak is not yet gone to New York I must request you to take measures to oblige him to go in." Dayton replied to Washington on 20 January 1783 explaining that Schaak was still his prisoner and that he had mounting debts. He goes on to say that "he pretends he expects money from New York to discharge them." It is not known when Schaak was eventually released.[74][75]

The journey home

Ambrose Vanderpoel writes: "Captain Asgill left Chatham on November 17th; and he hastened to New York intent upon taking the first ship to England. Finding that the packet Swallow, Captain Green, of Falmouth, had just sailed, he abandoned his servant and baggage, procured a row-boat, and succeeded in overtaking the vessel. He reached his native land in safety on December 18th."[76]

Mayo writes:[62]

As England nears, his trepidation grows. And when the Swallow drops anchor in the Thames — when he himself, in an hour or two, for better or for worse, must face the fact, the kindly captain of the packet another wayside Samaritan like Hazen, like Jackson, like Dayton, like the rest - must fain put all aside and go home with the boy to see him somehow over the crisis. Out, then, to Richmond they journey, where, on a tower-foundation of the ancient destroyed Palace of Sheen, Sir Charles has raised his country villa. But as the pair near Asgill House, young Charles can dare no more. Hidden amongst the trees by the river-bank, he waits while his friend feels out the ground. Bad news has indeed flown before them - has but lately arrived borne by young Asgill's own good-bye. Sure, now, that the word of the Crown of France had come too late, all the family has put on mourning. And the mother, no longer sustained by hope, has at last surrendered. Shut away in her room, she will see no one. So, in effect, the Swallow's captain is told when he knocks at Asgill House door. 'Very well,' said he to the footman, when other pleading failed, 'then say to her Ladyship that I have just now come from New York, that I have lately seen her son, and that perhaps things are less bad than she imagines.' Open flies the door, down runs the lady, the captain finishes his blessed task; and the rest, even after the lapse of a century and a half, seems too sacred for strangers' intrusion.

The Asgill family visit to Paris

A year later, starting 3 November 1783, Asgill together with his mother (who had been too ill to travel sooner) and his two eldest sisters, went to France to thank the King and Queen for saving his life. Asgill wrote in his Service Records: "The unfortunate Lot fell on me and I was in consequence conveyed to the Jerseys where I remained in Prison enduring peculiar Hardships for Six Months until released by an Act of Congress at the intercession of the Court of France". He goes on to say: "and had leave of Absence for a few months for the purpose of going to Paris to return thanks to the Court of France for having saved my Life."[77]

The Asgill family suffered

When writing about Asgill's eldest sister, Amelia, in relation to the events of 1782, Anne Ammundsen comments that: "when the family became aware that Charles was under threat of execution, Amelia went to pieces and suffered what today would be termed a 'nervous breakdown' and was quite inconsolable. She believed herself to be responsible for her brother's plight and couldn't forgive herself. [She had persuaded their father to allow Charles to join the army] An unknown (possibly Spanish) composer took pity on Amelia and wrote a piece of music for her, entitled 'Miss Asgill's Minuet', no doubt intended to lift her spirits".[78]

Writing to Sir Guy Carleton, the French Minister, M. le marquis de La Luzerne, wrote: "I shall send this resolution to France by different opportunities, and hope it will be forwarded immediately to Lady Asgill and put an end to the anxiety she has suffered on account of her son. But as it is possible that my letter may arrive later than yours, I beg you, Sir, to transmit it also by the first opportunity. I shall solicit General Washington to permit Captain Asgill to return to Europe on his parole, that Lady Asgill may have her joy complete, and if possible be recompensed for the alarm she has so long been in."[79]

The Aftermath

It was reported in The Reading Mercury (The Reading Mercury was Reading's first newspaper, published in 1723.[80]) on 30 December 1782, that Asgill (newly returned home following imprisonment in America) was at the levée for the first time since his arrival in town, and that Asgill's legs were still damaged from the use of leg irons.[81]

Following Asgill's return to England, lurid accounts of his experiences whilst a prisoner began to emerge in the coffee houses and press, and French plays were written about the affair.[82] Washington was angered that the young man did not deny these rumours, nor did he write to thank Washington for his release on parole.[83] Speculation mounted as to his reasons; Washington ordered that his correspondence on the Asgill Affair be made public.[84] His letters on the matter were printed in the New-Haven Gazette and the Connecticut Magazine on 16 November 1786, with the exception of his letter written to General Hazen on 18 May 1782, ordering him to include conditional prisoners in the selection of lots, in which he had violated the 14th Article of Capitulation.[85] Judge Thomas Jones states: "Colonel David Humphreys [Washington's former aide-de-camp] arranged and published them himself, not referring, of course, to Washington's agency in the matter..."[86]

It was five weeks before Charles Asgill was able to obtain a copy and sit down to read the account of his experiences, as recorded by George Washington. He wrote an impassioned response by return of post. His letter was sent to the editor of the New-Haven Gazette and the Connecticut Magazine,[87] but he is mistaken over the issue date - he should have written 16 November 1786. His letter begins:

Capt Asgills Answer to General Washingtons Letter &c Addressd to the Editor of the Newhaven Gazette

London Decr 20th 1786. Sir

In your Paper of the 24th August the publication of some letters to & from Genl Washington together with parts of the Correspondence which passd during my Confinement in the Jerseys renders it necessary that I should make a few remarks on the insinuations containd in Genl Washingtons Letter, & give a fair account of the Treatment I received while I remaind under the Singular circumstances in which Mr Washingtons judgment & feelings thought it justifiable & necessary to place [me] — the extreme regret with which I find myself oblgd to call the attention of the publick [sic] to a subject which so peculiary [sic] if not exclusively concerns my own Character & private feelings will induce me to confine what I have to say within as narrow a Compass as possible—

Asgill's 18-page letter of 20 December 1786, including claims that he was treated like a circus animal, with drunken revellers paying good money to enter his cell and taunt or beat him, was not published.[77] Supposedly left for dead after one such attack, he was subsequently permitted to keep a Newfoundland dog to protect himself.[88]

In this letter Asgill also wrote: "I have ever attributed the delay of my execution to the humane, considerate & judicious conduct of Sr Guy Carleton, who amusd Genl Washington with hopes & soothd him with the Idea that he might obtain the more immediate object of retaliation & Vengeance this Conduct of Sr Guy produced the procrastination which enabled the French Court particularly Her Majesty to exercise the characteristic humanity of that great & polishd nation ..."[34]

I leave for the public to decide how far the treatment I have related deservd acknowledgements – the motives of my silence were shortly these The state of my mind at the time of my release was such that my judgement told me I could not with sincerity return thanks my feelings would not allow me to give vent to reproaches[34]

The only letter from Asgill included in Washington's Papers, which were published in The New Haven Gazette and Connecticut Magazine, under the heading; "The Conduct of GENERAL WASHINGTON, respecting the Confinement of Capt. Asgill, placed in its true Point of Light", was his letter of 17 June 1782,[89] but this was printed with the date of 17 May (which was before lots were drawn). When writing it, Asgill was only just three weeks into his confinement, since being selected to atone for Huddy's death, by going to the gallows. He had been housed by Dayton for less than a fortnight, where he said he had been treated kindly, but then had become too ill to be moved to close confinement at Timothy Day's Tavern. Four years later, this one letter was presented as proof that that same kindness lasted for the next five months, which had not been the case at Timothy Day's Tavern. Only one Asgill letter; the absence of Asgill's letter to Washington, of 27 September,[90] in which he made it clear he was suffering greatly (asking Washington "to reflect on my unhappy Case, & to relieve me from a state, which those only can form any Judgment of, who have experienced the Horrors Attending it."); along with Washington's withheld letter of 18 May, ordering Hazen to include protected officers in the lottery, was presented as the "true point of light".[91]

Error of judgement

According to historian Peter Henriques, Washington made a serious error of judgement in deciding to revenge the murder of Joshua Huddy by sending a Conditional British officer to the gallows, writing: "Indeed the general's major error in judgment triggered the ensuing crisis."[92]

Henriques argues: "George Washington was notoriously thin-skinned, especially on matters involving personal honor. The general angrily responded that Asgill's statements were baseless calumnies. He described in considerable detail a generous parole he had extended Asgill and Gordon, forgetting that earlier he had tightly limited Asgill's movements. Calling his former captive 'defecting in politeness,' [Washington actually wrote "defective in politeness"]. he observed that Asgill, upon being repatriated, had lacked the grace to write and thank him".[83] In contrast to Henriques's account, Katherine Mayo writes that Asgill "seems to have published no statement at all concerning his American experience".[93]

Vanderpoel agrees: "His apparent willingness to sacrifice a capitulation prisoner in direct violation of a treaty which he himself had signed, (a willingness which English historians have declared to be the one blot upon the otherwise irreproachable character of the American hero)"[94]

Asgill's reputation

For two and a half centuries, accounts of the Asgill Affair have painted Asgill's character, during these events, as dishonest and deficient in politeness.[82]

Rumours about Asgill circulated, including that he had been taken to the gallows three times but led away on each occasion.[82] In his memoirs, Baron von Grimm wrote: "The public prints all over Europe resounded with the unhappy catastrophe which for eight months impended over the life of this young officer... The general curiosity, with regard to the events of the war, yielded, if I may so say, to the interest which young Asgill inspired, and the first question asked of all vessels that arrived from any port in North America, was always an enquiry into the fate of that young man. It is known that Asgill was thrice conducted to the foot of the gibbet, and that thrice General Washington, who could not bring himself to commit this crime of policy without a great struggle, suspended his punishment".[95] According to Anne Ammundsen, "Asgill became increasingly aware that his reputation was being besmirched by Washington, who felt aggrieved that Asgill had never replied to his courteous letter allowing him his freedom". Ammundsen notes that Asgill was "labelled a cad and a liar" for his refusal to deny the rumours about his experience as a prisoner. Ammundsen speculates that Asgill's silence was "perhaps [his] way of retaliating against the man who had threatened to take his life".[82]

As Katherine Mayo reports, when becoming aware of the rumours circulating, two of Asgill's American Westminster school-friends decided to take action to help their friend: "Yet, when the war was over and quiet days restored, Major Alexander Garden, late of Lee's Legion, like many another young American Revolutionary of his class and cultural background, betook himself straight to England eager to resume the connections of earlier time. ...[and] To Henry Middleton Garden turned. This is the page that the two American Old Westminsters brought forth: Garden first touches on Washington's conduct toward Asgill, not personally known to himself but noble and generous as he is sure it must have been. Then: I had been a school-fellow of Sir Charles Asgill, an inmate of the same boarding-house for several years, and a disposition more mild, gentle, and affectionate I never met with. I considered him as possessed of that high sense of honour which characterizes the youth of Westminster in a pre-eminent degree. Conversing sometime afterwards with Mr. Henry Middleton, of Suffolk, Great Britain, and inquiring if it was possible that Sir Charles Asgill, could so far forget his obligation to a generous enemy as to return his kindness with abuse, Mr. Middleton, who had been our contemporary at school, and who had kept up a degree of intimacy with Sir Charles, denied the justice of the accusation, and declared, that the person charged with an act so base not only spoke with gratitude of the conduct of General Washington, but was lavish in his commendations of Colonel Dayton [with whom Asgill spent his first weeks as a prisoner under threat of execution], and of all the officers of the Continental army whose duty had occasionally introduced them to his acquaintance [such as General Hazen, at the drawing of lots]. It may now be too late to remove unfavourable impressions on the other side of the Atlantic, (should my essay ever reach that far,) but it is still a pleasure to me, to do justice to the memory of our beloved Washington and to free from the imputation of duplicity, and ingratitude, a gentleman [Asgill] of whose merits I had ever entertained an opinion truly exalted. Whatever it may have effected in General Washington's behalf on the European side of the Atlantic, Garden's defence was powerless to save his school-mate's name in America. From note-makers such as Boudinot through the historians and essayists of the next half century, until the whole drama was forgotten few or none gave Asgill the benefit of the doubt."[96]

Allegations regarding Asgill's character were addressed in his letter to the New Haven Gazette and Connecticut Magazine, of 20 December 1786, which was published in The Journal of Lancaster County's Historical Society in December 2019, 233 years after it was written.[97] In the letter, Asgill wrote:

— the extreme regret with which I find myself oblgd to call the attention of the publick [sic] to a subject which so peculiary [sic]if not exclusively concerns my own Character & private feelings will induce me to confine what I have to say within as narrow a Compass as possible — very little is necessary to the anonymous letter of the American Correspondent, who boasts his introduction to Coffee house Sages & making his assertions on coffee house authority so confidently affirms that Charges were exhibited against General Washington, by Young Asgill of illiberal treatment and cruelty towards himself...

It is sufficient to say that this Gentleman whoever he is never took the pains of ascertaining the truth of the intelligence he received from his Coffee house sages, by an application to me, tho I almost resided Constantly in London & that by neglecting so to do he has exposd himself to the degrading circumstance of having positively asserted a groundless falsehood for I never did either suggest or countenance the report of a Gibbet having been erected before my prison Window — a Prison was indeed a Comfort that was denied me nor had the fact been so would it among the many indignities & unnecessary hardships I endurd...

— in Truth no Gibbet was erected in sight of my window Tho during my Confinement I was informd at different times & by various persons that in Monmouth County a Gallows was Erected with this inscription "up goes Asgill for Huddy" for the truth of this I cannot vouch as I never saw it myself...[34]

Vanderpoel writes of the lack of gratitude shown by Asgill, on his return to England, since it is assumed by him that Asgill was treated well: "Whether Asgill entertained any gratitude toward his captors for the kindness and forbearance with which he was treated while a prisoner at Chatham is very doubtful; it is more likely that he carried with him on his return to England a feeling of resentment toward those who had compelled him to pass through this trying period of anxiety and terror ... and he may have attributed the leniency with which he was treated [this is Vanderpoel's assumption - history has not recorded that Asgill was treated well, but Asgill had alluded to his state of mind and physical health in his letter to Washington of 27 September 1782 - history has only recorded that Washington's order was that he be treated with tenderness], and the delay in carrying his sentence into effect, to Washington's fear of the consequences of such an act, rather than to his tenderness and humanity." Whether Washington knew of the appalling treatment (which was the reality of Asgill's situation during his captivity) is not known, but Vanderpoel did not have the benefit of reading Asgill's account, written in 1786, since that document was hidden for two and a half centuries.[98]

In an interview with Anne Ammundsen, on 24 March 2022,[99] she maintains that Washington was aware of the mistreatment received by Asgill at Timothy Day's Tavern. She states that Asgill told Washington himself, drawing attention to the "horrors" and "suffering" being inflicted on him, in his letters to Washington of 27 September, when he wrote: "...I hope, will operate with your Excellency, to reflect on my unhappy Case, & to relieve me from a state, which those only can form any Judgment of, who have experienced the Horrors Attending it",[100] and on 18 October 1782 "if your Excelly could form an Idea of my sufferings I am convinced the trouble I give would be excused".[101] Yet these letters from Asgill, and Washington's orders to Hazen of 18 May 1782, (in which he violated the Treaty of Capitulation)[102] were not included in Washington's account of the Asgill Affair, "in Its True Point of Light", when published in the New Haven Gazette on 16 November 1786.[103]

The movements of Asgill's 1786 letter, which was published in 2019

Asgill's unpublished letter (which has been bound within a letterbook, preceded by David Humphreys's submission of copied Washington papers, which he sent to the New Haven Gazette for publication) was offered for sale in 1943, by Maggs Bros Ltd, 48 Bedford Square, London.[104] It was priced at £21 (£1,020 in 2022).[105]

It was once more for sale, by William Reese Co., New Haven, in 2003, priced at US$16,500.[106]

The letterbook was then auctioned at Sotheby's, New York City, on 13–14 April 2021, with an estimate of US$15–20,000. While some lots failed to sell, including Lot 514 (the letterbook), the items sold realised US$16 million for the late Ira Lipman.[107]

The Lipman Estate put the letterbook up for auction again, eighteen months later, by Doyle auctioneers of New York, on 16 November 2022, estimated at between US$8,000 and US$12,000.[108] It was unsold.

Asgill's letter had been published in the Winter 2019 issue of the Journal of Lancaster County's Historical Society 233 years after it was written.[15][97] At some point, over the centuries which have passed, Asgill's own attachments with his letter, together with the extra evidence he submitted at the "end of this narrative" have been removed (since they are not included in the letterbook, which is described in detail at the end of Sotheby's Lot 514 listing).[109]

Impact on Paris peace talks

Historian John A. Haymond notes that some commentators on the Asgill Affair "feared the legal controversy might derail the slow steps toward a peaceful resolution to the conflict that were already underway". Haymond notes that the British prime minister, Frederick North, Lord North, "in a secret dispatch to Carleton, wrote of his concern that the matter 'not provide an obstacle in the way of accommodation'".[110] Holger Hoock, however, attributes this quote to a letter to Carleton not from North but from William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, who became prime minister in July 1782.[111][112] After defeat at Yorktown in October 1781, North had remained as prime minister in the hope of being allowed to negotiate peace in the American Revolutionary War, but following a House of Commons motion demanding an end to the war, he resigned on 20 March 1782.[113] Peace negotiations leading to the Treaty of Paris, which eventually brought to an end the war, started in April 1782. American statesmen Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay negotiated the peace treaty with British representatives.[114] On 12 April 1782, the day Huddy was hanged by order of William Franklin, his father Benjamin was in Paris, where he was holding preliminary negotiations with a British official, and the hanging "was to have international repercussions and threaten the peace talks".[115]

Ambrose Vanderpoel writes: "Baron de Grimm is the authority for the statement that she [Lady Asgill] applied to the king, who directed that the author of a crime [Lippincott acting on William Franklin's orders] which dishonored [sic] the English nation should be given up to the Americans; but, incredible as it may seem, his command was not obeyed. Richard Oswald, a gentleman whom the British ministry had sent to Paris a short time before to sound the French government on the subject of peace, endeavored [sic] to persuade Benjamin Franklin, our representative at the Royal Court of Versailles, to exert his influence in Asgill's favor [sic]; but Franklin assured him that nothing but the surrender of Lippincott could save the prisoner's life." The irony is that Benjamin Franklin's son, William, was the author of the crime, but he may not have known this when he gave this response.[116] Thomas Jones has this to say about the British negotiator: "Richard Oswald, of Philpot Lane, London, merchant, was a Scotchman [sic] who had been a contractor for biscuits and provisions in Germany during the Seven Years' War."[117]

However, the preliminary articles of peace were signed on 30 November 1782 and the Treaty of Paris itself, which formally ended the war, was signed on 3 September 1783. The Continental Congress ratified the Treaty on 14 January 1784.[114] In a letter to Robert R. Livingston in January 1783, John Adams wrote: "The release of Captain Asgyll [sic] was so exquisite a Relief to my feelings, that I have not much cared what Interposition it was owing to— It would have been an [sic] horrid damp to the joys of Peace, if we had heard a disagreable [sic] account of him".[118]

Thomas Jones writes: "The American Commissioners objected to the form of Oswald's commission, and refused to treat unless it was altered. Oswald, upon this, desired Jay to draw such a one as would come up to his own wishes, which was done and sent to England, and so bent were the new Ministry upon a peace, that Jay's commission went through all the different forms, and was transmitted to Paris in a very few days, so that the British Commissioners absolutely acted under a commission dictated by the American Commissioners."[119]

The 5th Article of the treaty had been intended to protect Loyalists, but after the peace treaty had been ratified they suffered various humiliations; their properties and lands were confiscated, and they were disenfranchised. Jones continues: "But no sooner had America obtained her Independency, and the Colonies recognized by Great Britain as Independent States, than they pursued the very steps of the British House of Commons, the claims of which they had been opposing for more than eight years, and passed an act depriving a large body of people [the Loyalists] of the rights of election, declaring them forever disqualified from ever being either electors or elected, and then laying a tax upon then [sic] of £150,000, to be paid in the course of a year, and that in hard money. ... They [the Patriots] imprisoned, whipped, cut off ears, cut out tongues, and banished all, never to return on pain of death. Some were foolish enough to return and suffered accordingly. ... By the 6th Article it was agreed, 'that no future confiscations should be made, nor prosecutions commenced, against any person, or persons, for, or by reason of, the part which, he, or they, might have taken during the war, and that no person should on that account suffer any future loss or damage, in his person, liberty, or property'..." Jones goes on to write: "This Article was to be, at all events, evaded. It was too much in favour of the Loyalists."[120]

As reported in the New Jersey Courier, "...it is said that Jay and Franklin obtained valuable concessions in the treaty of Paris by agreeing to let Asgill go unharmed".[121]

Role of Major James Gordon

In his review of General Washington's Dilemma by Katherine Mayo, entitled "Only one hero – Major James Gordon", Keith Feiling writes that Mayo's book is, in some ways, a novel and as such deserves a hero. He maintains that the hero is not Washington – not the young Asgill and nor the murdered Huddy. The hero, he declares, was Major James Gordon of the 80th Regiment of Foot – [consisting of Edinburgh Volunteers]. Pointing out the many ways in which Gordon helped to change the disastrous path chosen for Asgill, he highlights that he worked to death to save his young charge. He helped Asgill face up to the fate handed to him; shared all the hardships of his imprisonment; "spurred Frenchmen and British and Americans to action" and in doing so shamed them all to eventually do the right thing. While he acknowledges that there have been other heroes in British military history, as anyone reading Sir John Fortescue and Winston Churchill knows, he says that Gordon's "plain courage and humanity shines in this ugly, tangled business". He thinks that all readers of Mayo's work should be grateful to her for bringing yet one more hero to the attention of all who care to read her book - "as the curtain falls on her intensely-wrought, moving, brief, and rounded tragedy".[122] On 8 March 2022, Trinity Church (Manhattan) erected a memorial stanchion in honour of Lieutenant Colonel James Gordon, 239 years after his death.

The Asgill Affair in literature

- A historical novel written by Agnes Carr Sage, Two Girls of Old New Jersey: A School-Girl Story of '76, was published in 1912. It follows the events of 1782, and Asgill's impending execution. This fictionalised account introduces Asgill as a romantic hero who becomes engaged to be married to a Loyalist schoolteacher, Madeline Burnham, in Trenton, New Jersey.[123][124]

- French author Charles-Joseph Mayer's 1784 novel, Asgill, or the Disorder of Civil Wars (French: Asgill, ou les désordres des guerres civiles), also tells the story of 1782.[125] Scholar Kristin Cook cites analysis of Mayer's book as an example of the critical attention the Asgill Affair has received, noting that "literary scholar Jack Iverson...reads the political impasse of its exposition as initially translated through two editions of Charles Joseph Mayer's 1784 French novel, Asgill, ou les désordres des guerres civiles...situating the American Affair, in relation to its French reception, as something of a dramatic Pièce de Théâtre. By introducing it as a reality-based plot that slides readily from fact into fiction, he illustrates a growing interest in the complex interconnections between 'real life' and 'imaginary conceit' among those affiliated with late eighteenth-century French print culture".[126]

- In his novel, Jack Hinton, The Guardsman (1892) by the Irish novelist Charles Lever he explains in his Preface "My intention was to depict, in the early experiences of a young Englishman in Ireland, some of the almost inevitable mistakes incidental to such a character. I had so often myself listened to so many absurd and exaggerated opinions on Irish character, formed on the very slightest acquaintance with the country, and by persons, too, who, with all the advantages long intimacy might confer, would still have been totally inadequate to the task of a rightful appreciation ..." Basing all his characters on real people, Sir Charles Asgill makes an appearance in Chapter 6 which covers the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and in Chapter 9 (which covers a dinner in Dublin) his wife Lady Asgill joins him "...anticipations as to the Castle dinner were not in the least exaggerated; nothing could possibly be more stiff or tiresome; the entertainment being given as a kind of ex officio civility, to the commander-of-the-forces and his staff, the conversation was purely professional, and never ranged beyond the discussion of military topics, or such as bore in any way upon the army. Happily, however, its duration was short. We dined at six, and by half-past eight we found ourselves at the foot of the grand staircase of the theatre in Crow Street"; and at the theatre "The comedy was at length over, and her grace, with the ladies of her suite, retired, leaving only the Asgills and some members of the household in the box with his Excellency." This was followed by a ball for the "Asgills, and that set" at which "above eight hundred guests were expected". In Chapter 17 Asgill is mentioned only very briefly.[127]

The Asgill Affair in drama

- D'Aubigny, (1815) Washington or the Orphan of Pennsylvania, melodrama in three acts by one of the authors of The Thieving Magpie, with music and ballet, shown for the first time, at Paris, in the Ambigu-Comique theatre, 13 July 1815.

- J.-L. le Barbier-le-Jeune, (1785) Asgill.: Drama in five acts, prose, dedicated to Lady Asgill, published in London and Paris. The author shows Washington plagued by the cruel need for reprisal that his duty requires. Washington even takes Asgill in his arms and they embrace with enthusiasm. Lady Asgill was very impressed by the play, and, indeed, Washington himself wrote to thank the author for writing such a complimentary piece, although confessed that his French was not up to being able to read it.[128] A copy of this play is available on the Gallicia website.[129]

- Billardon de Sauvigny, Louis-Edme, (1785) Dramatization of the Asgill Affair, thinly reset as Abdir Study of critical biography. Paris.

- De Comberousse, Benoit Michel (1795) Asgill, or the English Prisoner, a drama in five acts and verse. Comberousse, a member of the College of Arts, wrote this play in 1795. The drama, in which Washington's son plays a ridiculous role, was not performed in any theatre.

- de Lacoste, Henri, (1813) Washington, Or The Reprisal. A factual Drama, a play in three acts, in prose, staged for the first time in Paris at the Théâtre de l'Impératrice, on 5 January 1813. Henri de Lacoste was a Member of the Légion d'Honneur and l'Ordre impérial de la Réunion. In this play Asgill falls in love with Betti Penn, the daughter of a Pennsylvanian Quaker, who supports him through his ordeal awaiting death. The real William Penn (1644 – 1718) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England.