Mary Augusta Ward

Mary Augusta Ward | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mary Augusta Arnold 11 June 1851 Hobart, Tasmania, Australia |

| Died | 24 March 1920 (aged 68) London, England |

| Pen name | Mrs. Humphry Ward |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse | Thomas Humphry Ward |

| Children | Arnold Ward Janet Trevelyan |

| Relatives | Tom Arnold (father) Aldous Huxley (nephew) |

| Signature | |

Mary Augusta Ward CBE (née Arnold; 11 June 1851 – 24 March 1920) was a British novelist who wrote under her married name as Mrs Humphry Ward.[1] She worked to improve education for the poor setting up a Settlement in London and in 1908 she became the founding President of the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League.

Early life

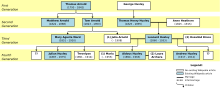

[edit]Mary Augusta Arnold was born in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, into a prominent intellectual family of writers and educationalists.[2][3][4] Mary was the daughter of Tom Arnold, a professor of literature, and Julia Sorell. Her siblings included writer and journalist William Thomas Arnold, suffrage campaigner Ethel Arnold, and Julia Huxley who founded Prior's Field School for girls in 1902 and married Leonard Huxley and their sons were Julian and Aldous Huxley.[5] The Arnolds and the Huxleys were an important influence on British intellectual life. An uncle was the poet Matthew Arnold and her grandfather Thomas Arnold,[6] the famous headmaster of Rugby School.[7]

Mary's father Tom Arnold was appointed inspector of schools in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) and commenced his role on 15 January 1850.[8] Tom Arnold was received into the Roman Catholic Church on 12 January 1856, which made him so unpopular in his job (and with his wife) that he resigned and left for England with his family in July 1856.[8] Mary Arnold had her fifth birthday the month before they left, and had no further connection with Tasmania. On arriving in England Tom Arnold was offered the chair of English literature at the contemplated Catholic university, Dublin, but this was only ratified after some delay.

Mary spent much of her time with her grandmother. She was educated at various boarding schools (from ages 11 to 15, in Shifnal, Shropshire[9]) and at 16 returned to live with her parents at Oxford, where her father had a lecturership in history.[10] Her schooldays formed the basis for one of her later novels, Marcella (1894).[11][12]

On 6 April 1872, not yet 21 years old, Mary married Humphry Ward, a fellow and tutor of Brasenose College, and also a writer and editor. For the next nine years she continued to live at Oxford, at 17 Bradmore Road, where she is commemorated by a blue plaque.[13] She had by now made herself familiar with French, German, Italian, Latin and Greek. She was developing an interest in social and educational service and making tentative efforts at literature. She added Spanish to her languages, and in 1877 undertook the writing of a large number of the lives of early Spanish ecclesiastics for the Dictionary of Christian Biography edited by Dr William Smith and Dr. Henry Wace.[14] Her translation of Amiel's Journal appeared in 1885.[15]

Ward supported the opening of Oxford University to female students. She was a member of the Lectures for Women Committee, which met from 1873 and organised courses of lectures with an optional final examination for women. With other members of the committee she formed the Association for the Education of Women, which supported the opening of halls for women students in Oxford.[16]

Ward became very involved in the negotiations surrounding the foundation of Somerville College in Oxford in 1879. She suggested that the new institution should be named after Mary Somerville. Ward was appointed as the first secretary of the Somerville Council and prepared for the arrival of new students despite being eight months pregnant when Somerville opened in October 1879.[17]

Career

[edit]

Ward began her career writing articles for Macmillan's Magazine[14] while working on a book for children that was published in 1881 under the title Milly and Olly. This was followed in 1884 by a more ambitious, though slight, study of modern life, Miss Bretherton, the story of an actress.[14] Ward's novels contained strong religious subject matter relevant to Victorian values she herself practised. Her popularity spread beyond Great Britain to the United States. Her book Lady Rose's Daughter was the best-selling novel in the United States in 1903, as was The Marriage of William Ashe in 1905. Ward's most popular novel by far was the religious "novel with a purpose" Robert Elsmere,[18] which portrayed the emotional conflict between the young pastor Elsmere and his wife, whose over-narrow orthodoxy brings her religious faith and their mutual love to a terrible impasse; but it was the detailed discussion of the "higher criticism" of the day, and its influence on Christian belief, rather than its power as a piece of dramatic fiction, that gave the book its exceptional vogue.[19][20] It started, as no academic work could have done, a popular discussion on historic and essential Christianity.[14][21][22]

Ward helped establish an organisation for working and teaching among the poor. She also worked as an educator in the residential settlement movements she founded. Mary Ward's declared aim was "equalisation" in society, and she established educational settlements first at Marchmont Hall and later at what is now called Mary Ward House on Tavistock Place in Bloomsbury. This was originally called the Passmore Edwards Settlement, after its benefactor John Passmore Edwards, but after Ward's death it became the Mary Ward Settlement. It is now known as the Mary Ward Centre and continues as an adult education college; affiliated with it is the Mary Ward Legal Centre.

She was also a significant campaigner against women getting the vote.[23][24][25][26] In the summer of 1908 she was approached by George Nathaniel Curzon and William Cremer, who asked her to be the founding president of the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League. Ward took on the job, creating and editing the Anti-Suffrage Review. She published a large number of articles on the subject, while two of her novels, The Testing of Diana Mallory and Delia Blanchflower, were used as platforms to criticise the suffragettes.[27] In a 1909 article in The Times, Ward wrote that constitutional, legal, financial, military, and international problems were problems only men could solve. However, she came to promote the idea of women having a voice in local government[28] and other rights that the men's anti-suffrage movement would not tolerate. Julia Stephen who was Virginia Woolf's mother recommended Florence Nightingale, Octavia Hill and Ward as good role models for her daughters.[29]

During World War I, Ward was asked by former United States President Theodore Roosevelt to write a series of articles to explain to Americans what was happening in Britain. Her work involved visiting the trenches on the Western Front, and resulted in three books, England's Effort - Six Letters to an American Friend (1916), Towards the Goal (1917), and Fields of Victory (1919).[12]

Ward was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1919 New Year Honours.[30]

Diarist (anonymous)

[edit]Throughout the 1880s Mary kept a personal diary of social and literary stories of the people she knew and met. She preferred to conduct her observations anonymously, and the diary was never published in her lifetime. Her reminiscences were heavily drawn upon by her friend Lucy B. Walford in a 1912 memoir[31] in which she is referred to simply as "Mary". Shortly after Mary's death in 1921 the diary was published, still anonymously, as Echoes of the 'Eighties: Leaves from the Diary of a Victorian Lady.[32] The identification of Mary Ward as the author of the diary was unknown until 2018 when an online article, about the diary's description of Oscar Wilde wearing a coat in the shape of a cello, cross-referenced her stories with corresponding information in the Walford memoir.[33]

Death

[edit]Mary Augusta Ward died on 24 March 1920, at 4 Connaught Square, London, and was interred at Aldbury in Hertfordshire, near her beloved country home Stocks three days later.[34]

Foundations, organisations and settlements

[edit]- Evening Play Centre Committee

- Mary Ward Centre, formerly the Passmore Edwards Settlement

- Women's National Anti-Suffrage League

Associated activists in social change

[edit]- Dame Grace Kimmins

Selected works

[edit]

- Fiction

- (1881). Milly and Olly.

- (1884). Miss Bretherton.

- (1888). Robert Elsmere.

- (1892). The History of David Grieve (3 vols.)

- (1894). Marcella (3 vols.)

- (1895). The Story of Bessie Costrell.

- (1896). Sir George Tressady.

- (1898). Helbeck of Bannisdale.

- (1900). Eleanor.

- (1903). Lady Rose's Daughter (dramatised as Agatha in 1905).[35][36]

- (1905). The Marriage of William Ashe.

- (1906). Fenwick's Career.

- (1908). Diana Mallory (published in America as The Testing of Diana Malory).

- (1909). Daphne, or 'Marriage à la Mode' (published in America as Marriage à la Mode).

- (1910). Canadian Born (published in America as Lady Merton, Colonist).

- (1911). The Case of Richard Meynell.

- (1913). The Mating of Lydia.

- (1913). The Coryston Family.

- (1914). Delia Blanchflower.

- (1915). Eltham House.

- (1915). A Great Success.

- (1916). Lady Connie.

- (1917). Missing.

- (1918). The War and Elizabeth (published in America as Elizabeth's Campaign).

- (1919). Cousin Philip (published in America as Helena).

- (1920). Harvest.

- Non-fiction

- (1891). Address to Mark the Opening of University Hall.

- (1894). Unitarians and the Future: Essex Hall Lecture.

- (1898). New Forms of Christian Education: An Address to the University Hall Guild.

- (1906). The Play-time of the Poor.

- (1907). William Thomas Arnold, Journalist and Historian (with C. E. Montague).

- (1910). Letters to my Neighbor on the Present Election.

- (1916). England's Effort, Six Letters to an American Friend.

- (1917). Towards the Goal (with an introduction by Theodore Roosevelt.)

- (1918). A Writer's Recollections.[37]

- (1919). Fields of Victory.

- Selected articles

- (1883). "French Souvenirs," Macmillan's Magazine 48, pp. 141–153.

- (1883). "M. Renan's Autobiography," Macmillan's Magazine 48, pp. 213–223.

- (1883). "Francis Garnier," Macmillan's Magazine 48, pp. 309–320.

- (1883). "A Swiss Peasant Novelist," Macmillan's Magazine 48, pp. 453–464.

- (1884). "The Literature of Introspection," Part II, Macmillan's Magazine 49, pp. 190–201, 268–278.

- (1884). "A New Edition of Keats," Macmillan's Magazine 49, pp. 330–340.

- (1884). "M. Renan's New Volume," Macmillan's Magazine 50, pp. 161–170.

- (1884). "Recent Fiction in England and France," Macmillan's Magazine 50, pp. 250–260.

- (1885). "Style and Miss Austen," Macmillan's Magazine 51, pp. 84–91.

- (1885). "French Views on English Writers," Macmillan's Magazine 52, pp. 16–25.

- (1885). "Marius the Epicurean," Macmillan's Magazine 52, pp. 132–139.

- (1889). "The New Reformation: A Dialogue," The Nineteenth Century 25, pp. 454–480.

- (1899). "The New Reformation II: A Conscience Clause for the Laity," The Nineteenth Century 46, pp. 654–672.

- (1908). "Some Suffragist Arguments," Educational Review 36, pp. 398–404.

- (1908). "Why I Do Not Believe in Woman Suffrage," Ladies' Home Journal 25, p. 15.

- (1908). "Women's Anti-Suffrage Movement," Nineteenth Century and After 64, pp. 343–352.[38]

- (1917). "Some Thoughts on Charlotte Brontë," In: Charlotte Brontë, 1816–1916: A Centenary Memorial. London: T. Fisher Unwin, pp. 11–38.

- (1918). "Let Women Say! An Appeal to the House of Lords," The Nineteenth Century and After 83, pp. 47–59.

- Miscellany

- (1879–1889). Personal diary. Published (1921) as Echoes of the 'eighties : leaves from the diary of a Victorian lady. London: Eveleigh Nash Co. Ltd.[39]

- (1899). Joubert: A Selection from His Thoughts; with a Preface by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- (1899–1900). The Life and Work of the Sisters Brontë. 7 vols.; with an Introduction by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- (1901). The Case for the Factory Acts, Ed. by Beatrice Webb; with a Preface by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- (1908). The Forewarners: A Novel, by Giovanni Cena; with a Preface by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- (1911). Ward, Mary Augusta (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). pp. 159–162.

- (1917). Six Women and the Invasion, by Gabrielle & Marguerite Yerta; with a Preface by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- (1920). Evening Play Centres for Children, by Janet Penrose Trevelyan; with a Preface by Mrs. Humphry Ward.

- Translations* (1885).

Amiel's Journal: The Journal Intime (2 vols.)

- Collected works

- (1909–12). The Writings of Mrs Humphry Ward. Houghton Mifflin (16 vols.)

- (1911–12). The Writings of Mrs Humphry Ward. Westmoreland Edition (16 vols.)

Filmography

[edit]- The Marriage of William Ashe, directed by Cecil Hepworth (UK, 1916, based on the novel The Marriage of William Ashe)

- Missing, directed by James Young (1918, based on the novel Missing)

- Lady Rose's Daughter, directed by Hugh Ford (1920, based on the novel Lady Rose's Daughter)

- The Marriage of William Ashe, directed by Edward Sloman (1921, based on the novel The Marriage of William Ashe)

References

[edit]- ^ Gwynn, Stephen (1917). Mrs. Humphry Ward. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- ^ McGill, Anna Blanche (1901). "The Arnolds". The Book Buyer. 22 (5): 373–380.

- ^ McGill, Anna Blanche (1901). "Some Famous Literary Clans. IV. The Arnolds Concluded". The Book Buyer. 22 (6): 459–466.

- ^ Sutherland, John (1990). Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, Pre-eminent Edwardian. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Harris, Muriel (1920). "Mrs. Humphry Ward". The North American Review. 211 (775): 818–825. JSTOR 25120533.

- ^ Stewart, Herbert L (1920). "Mrs. Humphry Ward". The University Magazine. XIX (2): 193–207.

- ^ Trevor, Meriol (1973). The Arnolds: Thomas Arnold and his Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ a b Howell, P.A. (1966). "Arnold, Thomas (1823–1900)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ Dickins, Gordon (1987). An Illustrated Literary Guide to Shropshire. Shropshire Libraries. pp. 74, 109. ISBN 0-903802-37-6.

- ^ Jones, Enid Huws (1973). Mrs Humphry Ward. London: Heinemann.

- ^ Johnson, Lionel Pigot (1921). "Mrs. Humphry Ward: Marcella," in Reviews & Critical Papers. London: Elkin Mathews.

- ^ a b Dickins, Gordon (1987). An Illustrated Literary Guide to Shropshire. p. 74.

- ^ "MRS Humphry Ward: Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Scheme".

- ^ a b c d Chisholm, Hugh (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). pp. 320–321.

- ^ Amiel, Henri-Frédéric (1885). Amiel's Journal. Translated by Ward, Mrs Humphry. London: MacMillan. p. Frontispiece.

- ^ Loader, Helen (2019). Mrs Humphry Ward and Greenian Philosophy: Religion, Society and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 85–86. ISBN 9783030141110.

- ^ "Mary Ward". Somerville College, Oxford. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Peterson, William S. (1976). Victorian Heretic: Mrs Humphry Ward's Robert Elsmere. Leicester University Press.

- ^ Phelps, William Lyon (1910). "Mrs. Humphry Ward." In: Essays on Modern Novelists. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Maison, Margaret M. (1961). "The Tragedy of Unbelief," in The Victorian Vision. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- ^ Mallock, M.M. (1913). "Newer Gospel". The American Catholic Quarterly Review. 38 (149): 1–16.

- ^ Lightman, Bernand (1990). "Robert Elsmere and the Agnostic Crises of Faith." In: Victorian Faith in Crisis: Essays on Continuity and Change in Nineteenth-century Religious Belief. Stanford University Press.

- ^ "An Appeal against Female Suffrage," The Nineteenth Century 25, 1889, 781–788.

- ^ Fawcett, Millicent Garrett (1912). "The Anti-suffragists," in Women's Suffrage. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, pp. 44–57.

- ^ Thesing, William B (1984). "Mrs. Humphry Ward's Anti-Suffrage Campaign: From Polemics to Art". Turn-of-the-Century Woman. 1 (1): 22–35.

- ^ Joannou, Maroula (2005). "Mary Augusta Ward (Mrs Humphry) and the opposition to women's suffrage" (PDF). Women's History Review. 14 (3–4): 561–580. doi:10.1080/09612020500200439. S2CID 144221773.

- ^ Argyle, Gisela (2003). "Mrs. Humphry Ward's Fictional Experiments in the Woman Question," Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 43, No. 4, The Nineteenth Century, pp. 939–957.

- ^ Fawcett, Millicent Garrett (1920). The Women's Victory – and After: Personal Reminiscences, 1911–1918. London: Sidgwick & Jackson, Ltd., p. 42.

- ^ Jane Garnett, 'Stephen, Julia Prinsep (1846–1895)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 6 May 2017

- ^ "No. 31114". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 January 1919. p. 451.

- ^ Walford, Lucy Bethia (1912). Memories of Victorian London. London: E. Arnold.

- ^ A Victorian Lady (1921). Echoes of the 'Eighties: Leaves from the Diary of a Victorian Lady. London: Eveleigh Nash Co. Ltd.

- ^ Cooper, John. Oscar Wilde In America :: Blog; accessed 16 January 2018 22:00

- ^ "Ward [née Arnold], Mary Augusta [known as Mrs Humphry Ward] (1851–1920), novelist, philanthropist, and political lobbyist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36736. Retrieved 8 October 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "WARD, Mrs. Humphry (Mary Augusta)". Who's Who. Vol. 59. 1907. p. 1835.

- ^ Whitaker, Joseph (1906). "Agatha". Almanack, 1906. London. p. 390.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ More, Paul Elmer (1921). "Oxford, Women, and God." In: Shelburne Essays, 11th series. Ed. More. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 257–287.

- ^ Gore-Booth, Eva (1908). "Women and the Suffrage: A Reply to Lady Lovat and Mrs. Humphry Ward". The Nineteenth Century and After. 64: 495–506.

- ^ "Echoes of the 'eighties : Leaves from the diary of a Victorian lady". 1921.

Bibliography

[edit]- Sutherland, John. Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, Pre-eminent Edwardian (Oxford University Press, 1990) ISBN 978-019818587-1 online

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Ward, Mary Augusta". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Ward, Mary Augusta". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). pp. 320–321.

Further reading

[edit]- Adcock, A. St. John (1903). "Mrs Humphry Ward". The Bookman. 24: 199–204.

- Beetz, Kirk H (1990). "Review of Mrs. Humphry Ward (1851–1920) A Bibliography". Victorian Periodicals Review. 23 (2): 73–76.

- Bellringer, Alan W (1985). "Mrs Humphry Ward's Autobiographical Tactics: A Writer's Recollections". Prose Studies. 8 (3): 40–50. doi:10.1080/01440358508586253.

- Bennett, Arnold (1917). "Mrs Humphry Ward's Heroines." In: Books and Persons. New York: George H. Doran, pp. 47–52.

- Bensick, Carol M. (1999). "'Partly Sympathy and Partly Rebellion': Mary Ward, the Scarlet Letter, and Hawthorne." In: Hawthorne and Women: Engendering and Expanding the Hawthorne Tradition. Ed. John L. Ido, Jr. and Melinda M. Ponder. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 159–167.

- Bergonzi, Bernard (2001). "Aldous Huxley and Aunt Mary." In: Aldous Huxley: Between East and West. Ed. C. C. Barfoot. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi, pp. 9–17.

- Bindslev, Anne M. (1985). Mrs. Humphry Ward: A Study in Late-Victorian Feminine Consciousness and Creative Expression. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Boughton, Gillian E. (2005). "Dr. Arnold’s Granddaughter: Mary Augusta Ward". In: The Child Writer from Austen to Woolf. Ed. Christine Alexander and Juliet McMaster. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 237–53.

- Bush, Julia (2005). "'Special Strengths for Their Own Special Duties': Women, Higher Education and Gender Conservatism in Late Victorian Britain". History of Education. 34 (4): 387–405. doi:10.1080/00467600500129583. S2CID 143995552.

- Collister, Peter (1980). "Mrs Humphry Ward, Vernon Lee, and Henry James," The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 31, No. 123, pp. 315–321.

- Courtney, W.L. (1904). "Mrs Humphry Ward." In: The Feminine Note in Fiction. London: Chapman & Hall, pp. 3–41.

- Cross, Wilbur L. (1899). "Philosophical Realism: Mrs. Humphry Ward and Thomas Hardy." In: The Development of the English Novel. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 268–280.

- Fawkes, Alfred (1913). "The Ideas of Mrs. Humphry Ward." In: Studies in Modernism. London: Smith, Elder & Co., pp. 447–468.

- Gardiner, A.G. (1914). "Mrs. Humphry Ward." In: Pillars of Society. London: James Nisbett & Co., Limited.

- Hamel, F. (1903). "The Scenes of Mrs. Humphry Ward's Novels," The Bookman, pp. 144–152.

- James, Henry (1893). "Mrs. Humphry Ward." In: Essays in London and Elsewhere. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

- Lederer, Clara (1951). "Mary Arnold Ward and the Victorian Ideal". Nineteenth-Century Fiction. 6 (3): 201–208. doi:10.2307/3044175. JSTOR 3044175.

- Lovett, Robert M (1919). "Mary in Wonderland". The Dial. 66: 463–465.

- Mabie, Hamilton W (1903). "The Work of Mrs. Humphry Ward". The North American Review. 176 (557): 481–489. JSTOR 25119382.

- MacFall, Haldane (1904). "Literary Portraits: Mrs. Humphry Ward". The Canadian Magazine. 23: 497–499.

- Murry, John Middleton (1918). "The Victorian Solitude". The Living Age. 299: 680–682.

- Norton-Smith, J (1968). "An Introduction to Mrs. Humphry Ward, Novelist". Essays in Criticism. 18 (4): 420–428. doi:10.1093/eic/xviii.4.420.

- Olcott, Charles S. (1914). "The Country of Mrs. Humphry Ward." In: The Lure of the Camera. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Phillips, Roland (1903). "Mrs. Humphry Ward". The Lamp. 26 (3): 17–20. PMID 5192334.

- Smith, Esther Marian Greenwell (1980). Mrs. Humphry Ward. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

- Sutherland, John (1988). "A Girl in the Bodleian: Mary Ward's Room of Her Own," Browning Institute Studies, Vol. 16, Victorian Learning, pp. 169–179.

- Sutton-Ramspeck, Beth (1990). "The Personal Is Poetical: Feminist Criticism and Mary Ward's Readings of the Brontës". Victorian Studies. 34 (1): 55–75.

- Trevelyan, Janet Penrose (1923). The Life of Mrs. Humphry Ward. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company.

- Walters, J. Stuart (1912). Mrs. Humphry Ward: Her Work and Influence. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Mary Augusta Ward at the Internet Archive

- Works by Mary Augusta Ward at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Mary Augusta Ward at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Mary Augusta Ward, at Hathi Trust

- Ward [née Arnold], Mary Augusta

- Mrs Humphry Ward – Victorian Fiction Research Guide

- Ward at the Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Mary Augusta Ward at The Victorian Web

- Works by Ward at The Victorian Women Writers Project

- Mary Ward Centre

- Women's National Anti-Suffrage League

- "Archival material relating to Mary Augusta Ward". UK National Archives.

- Finding aid to Mary A. (Mrs. Humphry) Ward papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Mrs. Humphry Ward Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Mrs. Humphry Ward Papers, Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library, Claremont, California.

- 1851 births

- 1920 deaths

- 19th-century English novelists

- 19th-century English women writers

- 20th-century English women writers

- 20th-century English novelists

- Victorian novelists

- Victorian women writers

- Huxley family

- Writers from Hobart

- English women novelists

- English Unitarians

- Female critics of feminism

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Pseudonymous women writers

- 19th-century pseudonymous writers

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers

- People associated with Somerville College, Oxford

- British anti-suffragists

- 19th-century English non-fiction writers

- English women non-fiction writers